Li Mullen is a host of talkooFEST, currently founding xSchool Mustio Coop and an aspiring event critic. They were educated in design (MA, Aalto University 2019) and live in-between Mustio and Helsinki in Finland.

Sue Guevara is a transdisciplinary conceptual artist and writer based in Helsinki, whose practice spans from music and visual arts, to poetry and journalistic writing. They advocate for a world free from the deadly grip of capitalism and Western imperialism — a new world forged from a love for life and an appreciation for the boundless beauty of our human existence.

Flow Festival is a 20-year-old institution and a focal point in Helsinki. Retrospectively, the Festival has grown into a prominent yet predictable place for nearly 90,000 people to see popular international musicians by strategically aligning with international trends. Its history conveys the desire for growth and the origins of its name to position itself as an entity looking to establish itself as a player in the urban development of Helsinki 1. The original vision to elevate the founders personal cultural preferences2 in the public milieu is now an almost inescapable reality, not only during the festival, but across the stronghold of nightlife businesses the founders operate, that hold the keys to club culture throughout the year.

The festival, established in 2004, set out to build a platform for the mass consumption of the founder’s taste, both in culture but especially in that of growth. Although the first few iterations of the festival may have felt like an independent countercultural experience, from the onset, the aim of the NuSpirit Collective was to create a festival that would bring “the hottest international talents to Helsinki"3. The About page on the Flow Festival website includes the founders motivation, vision, mission and values–the structure and the content reads like a corporate entity welcoming investment4. It describes its growth and global aspirations of prestige, inspiration from popular culture and place amongst the European festival scene. Flow Festival has become not only an institution but a small investment asset in the 550 billion-dollar portfolio5 of a global equity firm, as well.

The festival’s extensive programming, while impressive, feels increasingly curated for consumption. About 5006 unpaid volunteers contributed to the polished production and helped the company entity, Flow Festival Oy, make 1 million euros profit in 20237. Its glossy branding, massive pull, and significant influence are manufactured, in part, by 500 unpaid laborers into a carnivalesque cultural experience—complete with design talks and corporate sponsorships.

Its appearance does inspire “shadow” events and afterparties, but also brings a visible surge in police presence. The heightened activity around Flow, combined with practically unchecked police powers, leaves unaffiliated residents vulnerable to arbitrary, unlawful, and humiliating detentions, often driven by officers’ biases. Additionally, security personnel have been reported abusing their authority to harass festival-goers without consequence — yet these incidents seem to have no effect on ticket sales.

The festival’s extensive programming, while impressive, feels increasingly curated for consumption. About 5006 unpaid volunteers contributed to the polished production and helped the company entity, Flow Festival Oy, make 1 million euros profit in 20237. Its glossy branding, massive pull, and significant influence are manufactured, in part, by 500 unpaid laborers into a carnivalesque cultural experience—complete with design talks and corporate sponsorships.

This article critically examines Flow Festival’s evolving role within Helsinki’s cultural landscape, probing the festival’s values amidst its corporate transition against its growing notoriety. Is the festival’s primary objective still to enrich the local cultural scene, or has it become more about advancing the business interests of its new board members? It is thus timely and necessary to critically examine the role Flow Festival plays within Helsinki and the broader implications of its corporate growth; the complexities and contradictions that lie at the heart of Flow Festival.

Cultural Impact

As Flow’s audience increased, so did its budget—and with it, the festival’s appeal to corporate overlords. According to one longtime attendee, the shift away from an underground festival already apparent in 2011 when Kanye performed from a crane, but it was cemented with the sale to Superstruct. The festival’s headlining acts became increasingly dominated by mainstream, commercial names detached from any local narrative. As the festival’s influence continues to grow, it becomes clear that its impact extends far beyond its immediate surroundings, revealing a complex interplay between commercial interests, and broader sociocultural dynamics. Flow Festival is not merely a live entertainment event, but since 2018 a business entity owned by a "global live entertainment company with seasoned professionals that craft memorable experiences that amplify cultures"8. This financial transaction marked Flow’s transformation to an international investment asset. This financial transaction marked Flow’s transformation to an international investment asset. Superstructs stated mission is to build a "diverse portfolio of European festivals,"9 and Flow, once independent, in 2018 became a shiny bauble in its growing collection.

At first glance, it might not be apparent to many longtime Flow-goers, but what was once a uniquely Finnish experience has been commercialized and packaged for an international audience. The influx of foreign press—lured by aggressive PR campaigns in markets like the UK, France, and Germany—means that Flow is now as much about Helsinki being “discovered" by the world as it is discovering new music in Helsinki. In many ways, Flow has become a tourism product, another stop on the festival circuit for influencers and festival tourists looking to tick Helsinki off their bucket list.

The festival’s role as a gateway to the global music industry also underscores a significant power dynamic. Flow, on the surface at least, takes pride in providing a platform for emerging Finnish artists, offering them exposure to both fans and international journalists. For some, this annual showcase in Suvilahti’s post-industrial setting can be seen as an opportunity for international press coverage, to break into the global music industry and expand their careers beyond the borders of this country. For others, this is about maintaining their contracts with the venues affiliated with Flow’s ownership.

Flow Festival premises, 2024. Photo: Uzair Amjad

Flow Festival premises, 2024. Photo: Uzair Amjad

To really understand the dynamics in local bookings at Flow, one has to look at the venues and companies connected to it. Behind the scenes, Flow’s curatorial decisions have been shaped by the same network of owners in control of some of Helsinki’s most prominent nightclubs — Kuudes Linja, for example, where the alcohol sales from the festival also run through. Cross-referencing the board members of Flow Festival Oy and Kuudeslinja Oy reveals the local business executives who shape the strategy of nightclubs like Kaiku, Post Bar, Siltanen, and Aaniwalli.10 11 This conglomerate of venues is colloquially known as Kompleksi and also happens to be the stomping ground for many of the local acts that end up playing at Flow. Furthermore, in the artist’s bio’s, Flow’s often highlight their association with these venues, and typically omit other appearances at the plethora of notable live concert venues. This sort of exclusivity is made possible by the overlap between Flow’s ownership and Kompleksi which makes the festival feel like a closed loop.

Cultural events like Flow can also inadvertently become forces that buttress existing power structures by dictating trends, shaping public taste, and potentially marginalizing smaller, less commercially viable genres and their audiences. Following many trends set by the new champions of online music journalism, Flow Festival expanded its audience sixfold from 2006 to 2017.12 From 2006, where already 7 of the 18 artists that performed had earned a BNM ranking from Pitchfork, that continued to grow until 2016 with 24.13 14 Over the years, Flow has built its reputation by featuring popular and critically acclaimed international artists across genres like dance, electronic, R&B, and indie but the festival’s choices in programming seem to reflect the cultural capital determining commercial viability and the founders other business interests.

Flow Strike

Details were announced this summer about the global private equity firm, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. Inc. (KKR), purchasing the festival.15 The billion-euro corporate shifts behind Flow’s curtain aren’t just an abstract business deal—they have real implications for what the festival represents. The impact of KKR’s purchase brings about broader anxieties about the commercialization of cultural spaces and the ethical considerations surrounding festival management, especially as KKR has Israeli and Zionist holdings in its portfolio.16

In July 2024, Flow Festival’s opening day saw the launch of the “Flow Strike” campaign, by a Helsinki-based collective of pro-Palestinian artists and performers seeking to expose Flow’s entanglement with global capital. Upon the gates first opening Friday, the members of Megabondmon were among the first artists to stage a protest within the festival grounds and just before close Grande Mahogany was among the last. By the end of the weekend, several artists performing this year joined the movement. Their primary grievance centered around Flow’s recent acquisition by KKR & Co. Inc., from Palestine’s colonization through investments in Israeli companies. Flow Strike’s message was clear: the festival, through its new ownership, risks complicity in supporting the Israeli regime’s ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people. By occupying the very space of the festival, Flow Strike delivered a pointed critique of the corporate powers behind the event. This action, inspired by the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement, and Strike Germany, positions itself within the global network of resistance underscored how subtly settler-colonial violence and capitalist interests are woven into public events. The illusion of festivals as apolitical spaces was shattered as Flow Strike reminded festival-goers of the bloodshed being funded in Palestine—something that could no longer be ignored.

Flow Strike’s website lists demands17: Flow Festival must create ethical guidelines, dissociate from partners linked to Israel, and have KKR divest from Israeli companies. They also call for public accountability and insist that Flow match its proclaimed values of “justice, equity, and equality” with real action. These are demands about integrity — being held accountable to their purported values. Flow’s spokesperson Paavo Kässi claims that Flow understands that “the humanitarian catastrophe in Palestine is a shocking issue, and we believe giving it visibility is extremely important”.18 The campaign, however, took concrete actions towards the festival considering its genocidal connection.

Flow Festival Back yard. Photo: Uzair Amjad

Direct action organised by Flow Strike on the first day of the festival, 2024. Photo: Sue Guevara

Shadow Flow event organised by Flow Strike, 2024

Shadow Flow event organised by Flow Strike, 2024

Although Flow Strike shares a position of resistance with Strike Germany, a Pro-Palestine movement resisting the German state’s efforts to suppress solidarity with Palestine. A recent policy update by the Berlin Senate’s forces artists, performers, and other cultural workers collaborating with state-funded institutions to adhere to a controversially ambiguous definition of antisemitism19 that essentially bans critiques of Israel’s policies. Yet, when compared with Strike Germany’s manifesto, Flow Strike’s open letter and FAQ feel a bit haphazard. While Strike Germany aims for systemic change within German state policies, Flow Strike makes a demand for divestment from strategic assets from a behemoth multinational investment firm. That is far removed from the more realistic call to workers to exert their very-real influence on public policy and culture. The limitations of festival-level activism quickly become apparent: how can local movements dismantle systems that span continents and intersect issues like settler colonialism and climate justice? The truth is that it would have been more reasonable to pressure Flow to denounce KKR for its complicity, for example.

Flow Strike reminds us that the violence faced by Palestinians is part of a global system of oppression linking indigenous struggles, neoliberal politics, and capitalist greed. Festivals, like all cultural institutions, are shaped by the same powers that perpetuate inequality and exploitation. Flow Strike has already shown that it’s willing to confront these forces. The question is: how far is it willing to go to dismantle them, and with what strategy?

Despite its lofty goals, the action also fell short of a fully-fledged strike. Many artists who supported the collective effort still performed-citing binding agreements with the festival-and ultimately collected pay from the festival. Surely this was complicated by the sixth line connection — but are these businesses not now complicit as well? This tension between critiquing the system and participating in it reflects a perennial dilemma—grassroots protest within capitalist spaces must avoid co-option, lest it reinforce the system. In Flow Strike’s case this is still unclear, as it could even have served as PR for Flow, or truly started something new.

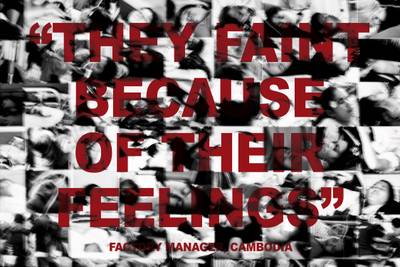

Flow Strike made a powerful statement, though, when spokesperson Jenna Jauhiainen explained, "refusing to perform is less effective than taking the stage and forcing 90,000 people to confront the fact that this joyous celebration is stained in blood"20. This shows Flow Strike did what it could with limited resources and in a very short timeframe, but with more time and a stronger reputation, a true strike could have materialized. Although the campaign will likely go unnoticed by KKR, Flow Strike should continue to put pressure on Flow Festival and perhaps try to align with activists across the Superstruct network to Strike Superstruct together.

Flow Strike reminds us that the violence faced by Palestinians is part of a global system of oppression linking indigenous struggles, neoliberal politics, and capitalist greed. Festivals, like all cultural institutions, are shaped by the same powers that perpetuate inequality and exploitation. Flow Strike has already shown that it’s willing to confront these forces. The question is: how far is it willing to go to dismantle them, and with what strategy?

Illegal Free Labor

Amidst the influx of tourists, exists the exploitation of free labor. In 2023 alone, about 500 unpaid volunteers21 were recruited to help make the festival run smoothly. These volunteers aren’t paid for their work, yet they perform crucial tasks that keep the festival’s operations afloat. Their reward? A wristband that grants access to the festival—an item which, according to Finnish, should be declared as taxable income. But Flow Festival doesn’t recognize this wristband as a reward, instead labeling it as a mere “pass.”

Flow Festival CEO Suvi Kallio’s spin on the narrative is that many people want to break into the event industry by volunteering. But let’s be real—volunteerism at this scale is nothing short of exploitation. To add insult to injury, Flow Festival Oy made a staggering profit of over one million euros in 2023, with a turnover of 9.8 million euros.22 The profit was paid out entirely as dividends into the pockets of shareholders.23 Although exactly when is unclear, Flow has turned into your average shady capitalist venture, using free labor to generate enormous profit and then funneling that wealth upward. The workers, meanwhile, are left with a wristband that they legally need to report as taxable income. This is an unacceptable practice that isn’t just about a couple of free wristbands; it’s about the normalization of a labor model where workers are expected to perform for free while the corporate owners reap all the rewards and calling it a “volunteer opportunity” doesn’t change that. The festival—and its shareholders—should be held accountable for their exploitation of workers and forced to address this systemic issue with real change, not PR-friendly excuses, like the ones Kallio presented.

Security Concerns and Controversies

Behind the surface of Flow Festival’s commitment to justice, equity and equality: many attendees and even artists find themselves subject to security and police overreach. For a festival that markets itself as a beacon of inclusivity and progressive culture, the environment just beyond its fences can feel unnervingly authoritarian. The following abuses of power, which range from aggressive detainment to outright physical assault, paint a troubling picture of how security is managed at Flow. Far from being an isolated event, this pattern of behavior stretches many years, with accounts of violence, intimidation, and humiliation coming from both local attendees and international visitors.

Artist Abuse in International Headlines

One of the most egregious examples of security abuse at Flow Festival came in 2017, when Russian DJ Inga Mauer was assaulted by local security personnel after her Saturday night closing set24. Mauer, who was reportedly “beaten up and jailed,” endured an attack that brought international attention to the darker side of the festival. Flow Festival publicly apologized for the incident, but it was impossible to ignore the reality of what had transpired: an artist, invited to perform at the festival, was brutalized by those hired to protect her. The entire situation raised serious questions about how security and police operate during the festival, particularly when no clear accountability exists.

The security company contracted in 2017, Local Crew Ltd., defended its actions through a dismissive statement from its CEO, Jarmo Ketonen. In his remarks, Ketonen implied that Mauer’s detainment was justified because, in his view, “innocent people don’t spend the night in custody in Finland.” The audacity of such a claim, following well-documented reports of abuse, speaks to the entrenched relationship between private security and police during Flow Festival. This sentiment—that those detained must have done something wrong—is a foundation for the abuse that continues to occur year after year.

A Pattern of Intimidation and Abuse

Although the security contractor has changed, the situation with Inga Mauer is not unique. In interviews conducted with Flow attendees, we uncovered multiple incidents of security guards and Helsinki police who use their authority to intimidate and abuse, often with little or no justification. These accounts reveal a disturbing pattern of behavior that should tarnish the festival’s reputation but go largely unnoticed.

Hal’s Story: A Humiliating Encounter

Hal’s experience at Flow this year is just one of many instances where security overstepped their boundaries. After the festival ended on Saturday, Hal was separated from his friends. Their meeting place was about 60 meters away. When asked about reaching them, the security guard directing traffic told Hal to ask his supervisor nearby. What followed was a shocking display of power by the festival’s security staff. As Hal approached a supervisor to explain his situation, the encounter quickly escalated. Without warning, the security supervisor grabbed Hal’s arm, accusing him of smelling like weed—a baseless claim that spiraled into a full-on physical restraint.

Despite having no illegal substances on him, Hal was searched, his bag rifled through, and his body restrained by multiple guards. What made the situation even more horrifying was the invasive nature of the search: security personnel not only searched Hal’s belongings but went as far as to open his pants, exposing the surgical scars he had warned them about. “It was humiliating,” Hal recounted. “I told them I had recently had surgery, but they didn’t care.” The experience left him shaken, ashamed, and deeply disappointed in how Flow handled security.

Andy’s Story: Violated by the Police

Andy, another long-time attendee, shared his own story of being searched and violated by the police in a separate incident. “I was just hanging out, enjoying the festival, when I was suddenly pulled aside by the police,” Andy said. “It wasn’t a normal pat-down; it felt invasive, like they were intentionally overstepping.” The police didn’t give Andy a reason for the search, leaving him feeling angry, embarrassed, and > humiliated in a public setting.

While Andy had enjoyed some of Flow’s earlier years, the trauma from the latest experience totally soured his opinion of the future. “It really left a bad taste in my mouth. I’ve been going to Flow for years, but after that incident, I started noticing things about the festival I hadn’t seen before—especially how it has changed over the years.” The shift from a more intimate, community-focused event to a commercialized, corporate-run spectacle has only amplified these issues. Andy’s story, like Hal’s, speaks to a broader trend of unchecked power at Flow, where both security and police have carte blanche to act with impunity.

Special Powers and Stop-and-Search Sunday

One clause in the Police Act grants police the ability to conduct stop-and-search operations within the immediate vicinity of the public event. The law specifies that searches should be conducted only when there’s justifiable concern that the person may pose a threat to others or the event. The festival and the surrounding neighborhoods fall under special police powers that allow for more aggressive enforcement than would normally be acceptable in Helsinki. These temporary allowances give police the authority to stop and search anyone within the ‘immediate vicinity’ of the festival.25

The actions of police officers and especially the timing of their operations feel coordinated with the festival to potentially extract the last euros from attendees and people in the neighborhood. We’ve heard that smoking a cigarette rolled with organic paper has justified interrogations and searches both on and off the festival ground; one person experienced this tactic 900m from the closest point of the festival — Pengerpuisto.

Nenu’s story: between home and work

“You know how it is, the police show up on the last day, targeting people as they’re leaving and handing out fines without really intruding on the festival itself. I hear the same stories every year. There’s this loophole in Finnish law that allows police to conduct stop-and-search operations at large events, which would otherwise be illegal. But the thing is, I wasn’t even near the festival at the time. I was sitting in a courtyard, on private property, about 100 meters away from the entrance. There were two sidewalks and a four-way intersection between me and Flow. It didn’t make sense for them to say I posed any kind of threat to festival security.”

“I was in a black tracksuit, which maybe made me look ‘suspicious’ to them. But they did end up finding an empty speed bag and like 0.05g of weed, which is basically an un-smokeable amount (chuckles). They started grilling me right away, asking if I was a user or a seller. One of them even lied to me, saying that any amount of drugs is considered a sellable amount, which isn’t true under Finnish law.”

Nenu goes on to describe how the officers escalate the situation. “Three undercover cops escorted me to this storage room that had three metal walls, with two of them standing at the open end, basically blocking me in. Then they kept questioning me, even about my name. They asked for my real name, and when I told them, they were like, ‘Really? What was your name before you changed it?’ It felt like they were suspicious just because I have a foreign-sounding name, even though I have a Finnish social security number."

“They fined me 200 euros. But it didn’t stop there—months later, I got the police report, and it was full of lies. For starters, they exaggerated the amount of drugs I had. They also claimed that one of their officers had offered me support to quit drugs and had given me contact info for a drug polyclinic. That never happened. They fined me for the drugs but then put them back in my wallet. Why? It all felt sketchy and like they were just trying to close the case without following proper procedures.”

Nenu then went on to describe how it affected them since. “It’s messed with me a lot, to be honest. The whole illusion of safety is gone. I mean, can I even leave my house during Flow weekend anymore without worrying? I’ve even stopped smoking with brown papers because they can look like joints. I don’t want to give them any more excuses to target me again."

In Nenu’s case, it seems the police stretched Section 12 by conducting a stop-and-search far outside the festival’s immediate area, using vague suspicion based on appearance, and escalating the situation beyond what the law likely intended. They may have exploited the law’s loophole to target individuals for minor infractions, potentially for monetary gain through fines.

The temporary nature of the police presence creates an atmosphere of fear and tension for some. One that makes residents feel unwelcome in their own neighborhoods. The unchecked power granted to police only exacerbates this problem, creating an environment where abuse thrives. It should be the responsibility of Flow Festival to clarify the conduct of the police protecting their event, specifically, to understand what “immediate vicinity” means to make residents less fearful of. Only by reforming its security practices, advocating for policy changes, and fostering genuine relationships with local communities can Flow begin to rebuild its cultural credibility.

In the end, the festival’s transformation raises critical questions about the balance between creativity, community, and corporate interests — questions that every attendee should consider before stepping onto the festival grounds.

How will Flow Festival respond to criticisms about its relationships with its free workforce, security contractors, Helsinki Police and its Zionist holding company? Will it align with or distance itself from the actions and affiliations of its financial backers? As Flow Festival will evolve under the stewardship of KKR, visitors should be mindful of the relatively simple dynamic at play. The festival’s ownership and financial structure inevitably shape its cultural offerings and ethical considerations. By participating, attendees contribute not only to the festival’s success but also to the larger systems of capital and influence that sustain it. This growing entanglement between culture, commerce, and politics challenges the notion of cultural spaces as neutral and the power structures that shape our experiences of festivals like Flow. In the end, the festival’s transformation raises critical questions about the balance between creativity, community, and corporate interests — questions that every attendee should consider before stepping onto the festival grounds. And so, the question remains: what is Flow’s place in Helsinki’s future? Flow may continue to thrive as a business, but for how long will it have any credibility as a cultural institution?

One week after Flow, at the corner of the festival grounds, you can find several large dumpsters full of metal, wood and furniture. Amongst them many treasures… Martela sofas, large canvas pieces from the tents, tools, some trash and many rolls of black PVC fence cladding. We inherit some of these items in hopes that one day, with a collective who seek, we build our own festival. Flow Festival may be too problematic to save, but it is also inescapable.

One of four dumpsters on south-east side of Suvilahti one week after flow festival. Photo: Li Mullen