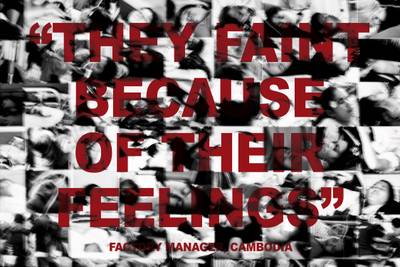

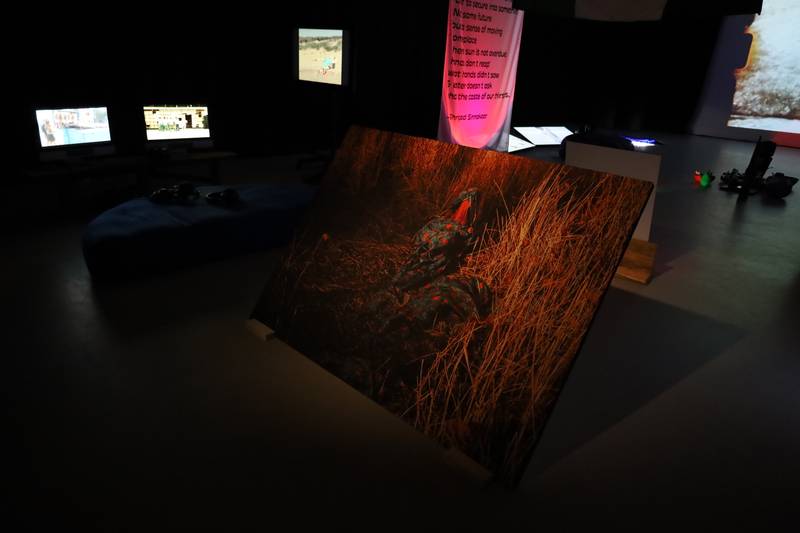

Feat. Photograph by Rafiki, Untitled, 2021. Installation view RESONANCE BEYOND ESCAPE: QWORKAHOLICS ANONYMOUS III at NAC of Vilnius Academy of Arts, 2024. Photo: Party Office

Santa Hirša works as an independent art historian and critic based in Riga, Latvia, and has received ‘Normunds Naumanis Award in Art Criticism (2021)’. She is the author of monographs about artists Krišs Salmanis (2018) and Andris Breže (2020), editor of multiple publications and collections of articles. Her research focuses on late socialist and postsocialist visual art and contemporary art processes.

There are relatively few works on display in the Resonance Beyond Escape: Qworkaholics Anonymous III exhibition, yet it reveals a vast cultural landscape shaped by intense and multi-layered experiences. These experiences are borne by people who, to quote the curator, are facing “burnout from the incessant need to engage in the very acts of survival, living in an inequitable human society that tends to render people unworthy if we don’t serve its material interest.” The – “Qworkaholics” in the exhibition title is a pun combining “queer”, “workaholic”, and “alcoholics anonymous”, bringing together references to practices of self-discipline and self-healing and anonymity as a need to cover up and suppress one’s identity. At the same time, the play on the meanings of these words and the very method of play in the title also invoke the internal logic and scenography of the exhibition – set up as a collective game that inverts commonplace notions, the meanings of concepts, and makes participants and visitors lose themselves in a game of hide & seek. This also resonates with the title of the exhibition’s curator – Party Office. Party Office is founded and directed by artist-curator Vidisha-Fadescha, who describes themselves as an anti-caste, anti-racist, trans-feminist, art and social space and time. They are building translational dialogues on empathetic futures, care communities and radical agency from a queer anarchist position. Qworkaholics Anonymous is a longstanding project of Fadescha; Part I (2020) and Part II (2022) took the form of video works, while Part III comprises an artist residency and an exhibition at Nida Art Colony of Vilnius Academy of Arts (NAC).

The exhibition’s imaginative structure is driven by a subtle, precise metaphor (embodied in its title) that applies the clichés of an affluent Western lifestyle to bodies and identities that do not fit into Western heteroimperialism (a term used by philosopher Tadas Zaronskis in his review1). Qworkaholics are victims of various colonial systems of power. Their “primary occupation” is the struggle for survival in the present-day world, which systematically is “othering” them, subjecting their bodies, identities and affects to daily violence and oppression. The experiences narrated in the exhibition seek to reshape these power dynamics and effect a decolonization from a Western anthropological gaze that is as exhausting and draining as any other toxic work environment. But is this comparison even adequate given that the Qworkaholics’ relationship with the outside world is suffused with oppression and social mistreatment at the most basic (desire, instinct, sensibility) level? How can these relationships be reshaped if burnout is at the very core of one’s existence, not just a part of it?

Feat. Anna Ehrenstein, The Hypnotization of the Cloud, 2022. Installation view RESONANCE BEYOND ESCAPE: QWORKAHOLICS ANONYMOUS III at NAC of Vilnius Academy of Arts, 2024. Photo: Party Office

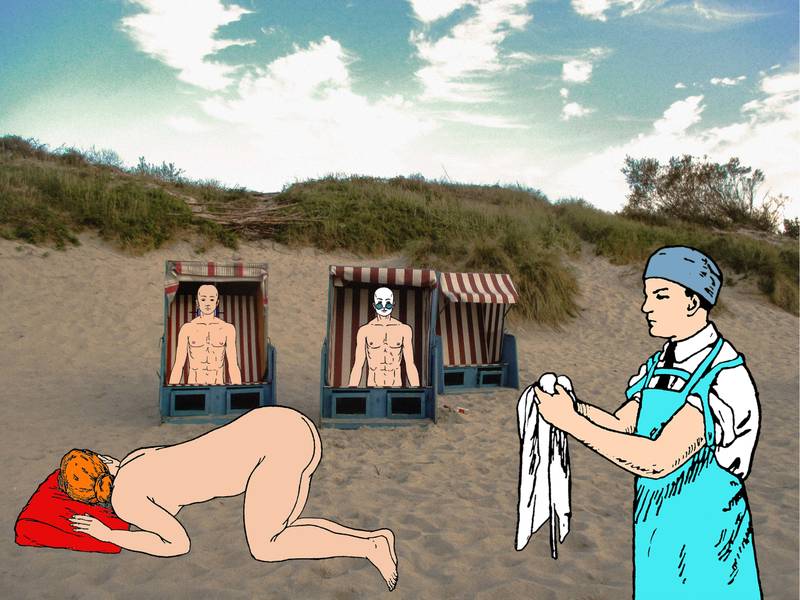

Gabriele Gervickaite, Show Analysis 03, Digital collage, 2018

Entering the exhibition space evokes associations with an entertainment venue – there’s music, semi-darkness, active light elements, movement, noise, bright props, flashes, bursts of colour, etc. It is initially quite difficult to completely focus on a single exhibit, as the nearby works distract one’s attention. Such a state of diffused focus is reminiscent of small talk at a party, when the setting only allows for short, distracted conversations, for passing from one encounter to the next and later and trying to piece together where you left off – over and over again. The jerky rhythm of Resonance Beyond Escape. Qworkaholics Anonymous III owes not to a lack of interest but rather to the intensity, the flashy, blurry and even fluid nature of the environment and the visual qualities of the artworks. The constant need to refocus also characterizes states of burnout and overload, so the exhibition’s environmental cues can be interpreted as a conscious curatorial strategy aiming to reconstruct its’ cognitive circumstances. While burnout is associated with work, the exhibition is the opposite of a sterile, monotonous working environment whose function is to stimulate concentration. In contrast, Qworkaholics Anonymous III is visually vivid, colourful and saturated, full of songs, dances, and bodies. Several works can be viewed lying down, half lying down, or reclining, thus treating the experience of viewing the exhibition as leisure rather than labour.

Elements of carnivalism, irony, subversion and playfulness thread through the exhibition, but they do not tend to become comical or meretricious. They emphasise the contrast between the severity and fundamental existential significance of the issues raised by the artworks and the need to articulate them under the reinvigorative conditions of recreation. ‘The-exhibition-as-a-party’ seems to be a deliberate way of resisting the patriarchal, bureaucratic and binary capitalist world order, where everything is subjected to economic interests, the binaries between centre and periphery, white and non-white or any other false, toxic dichotomies. The dreamlike and performative mood of the exhibition acts as a mechanism of opposition to Western cultural narratives that embody seriousness and productivity, such as the “Is there life after work?” type of capitalism, subordinating every existing thing to profit. The party, the carnival and the recreation can be seen as spaces of liberation in living conditions largely dictated by the mechanisms of self-repression and forgetting or even unlearning.

It is significant that there is almost no documentalism or other journalistic types of expression in the exhibition, seemingly expressing a distrust of these forms of representation as embodying the myth of objective truth and expressing the power of the gaze that subjugates the other to one’s own vision. Self-narratives and self-performances manifest radical agency and respect for oneself, as well as the necessity to speak one’s own language and tell one’s own stories without intermediaries.

Resonance Beyond Escape. Qworkaholics Anonymous III takes place at the NAC, a subdivision of Vilnius Academy of Arts located in Nida, Lithuania, on the shore of the Curonian Spit, which separates the Curonian Lagoon from the Baltic Sea and is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Some of the works on display were made during a residency at the NAC and evoke the geographical conditions of the surrounding landscapes, the sea, the beach, and a certain remoteness. Water becomes a pervasive motif in several works and can be read as a burnout “retardant”. In some works, for example, a video by ‘The Albanian Conference’ (Anna Ehrenstein, Fadescha, Rebecca Pokua Korang, DNA), water is also associated with the burnout of the planetary ecosystem, where climate disasters, such as forest fires, are consequences of this literal burning out of the globe. Resonance Beyond Escape features a number of similar symbols and metaphors that flourish in a rich multiplicity of meanings, free from unequivocality and didacticism, simultaneously pointing to several states and occurrences, floating from one association to another. For example, in Malik Irtiza’s work ‘In search of apples, almonds and cherries’ (2022–ongoing), we see a black figure that finds and carries a tongue through Kashmir’s valleys. The tongue as object and symbol evokes restrictions on freedom of speech, as well as corporal punishment; it also makes one think about spice and gustatory tales as historical means of exoticizing the East and specifically the Kashmir region, the artist’s birthplace and a location experiencing extraordinary upheaval at this time.

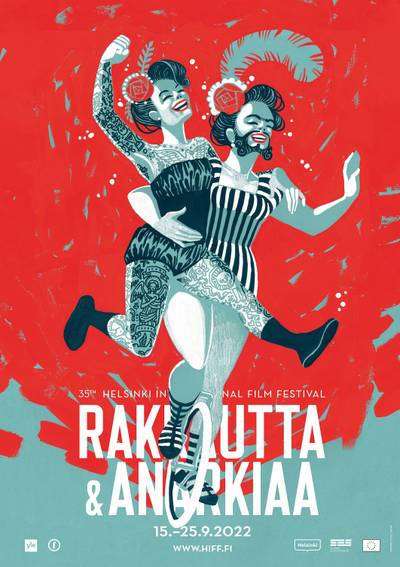

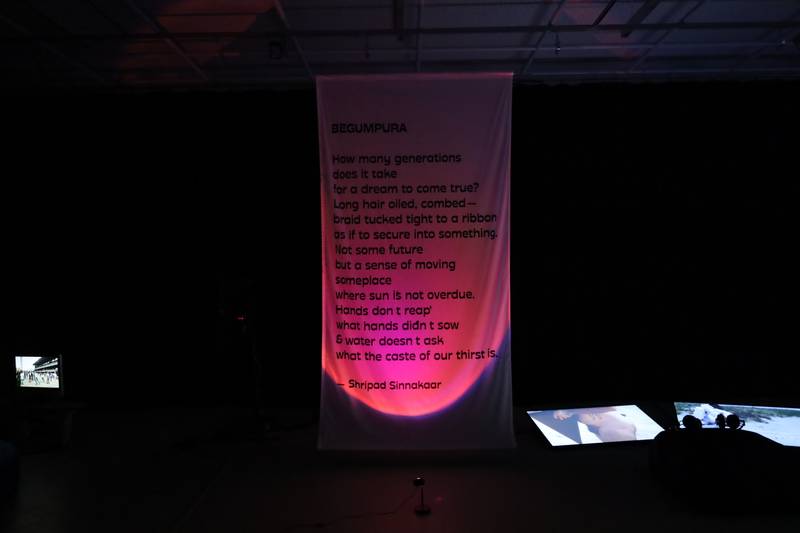

Feat. Poetry, Shripad Sinnakar, Begumpura, 2022. Installation view RESONANCE BEYOND ESCAPE: QWORKAHOLICS ANONYMOUS III at NAC of Vilnius Academy of Arts, 2024. Photo: Party Office

The entire exhibition can be characterised as a web of powerful symbols that resist translations, akin to poetry, which only hints at the message and then blurs it into associations and imagery. The poem ‘Begumpura’ by poet Shripad Sinnakaar is also exhibited as an autonomous work, printed on textile, and thus does not serve just as an accompanying text. It is significant that there is almost no documentalism or other journalistic types of expression in the exhibition, seemingly expressing a distrust of these forms of representation as embodying the myth of objective truth and expressing the power of the gaze that subjugates the other to one’s own vision. Self-narratives and self-performances manifest radical agency and respect for oneself, as well as the necessity to speak one’s own language and tell one’s own stories without intermediaries. Most of the works ironically re-enact and repeat the social rituals of neoliberalism or turn to folkloristic practices and meditative, self-shamanic practices.

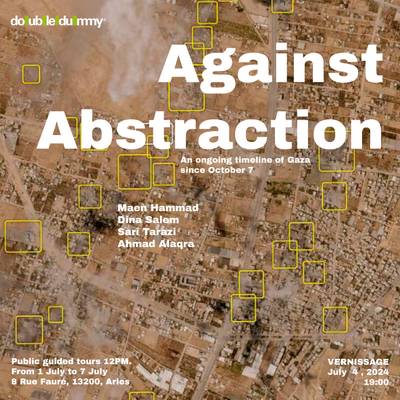

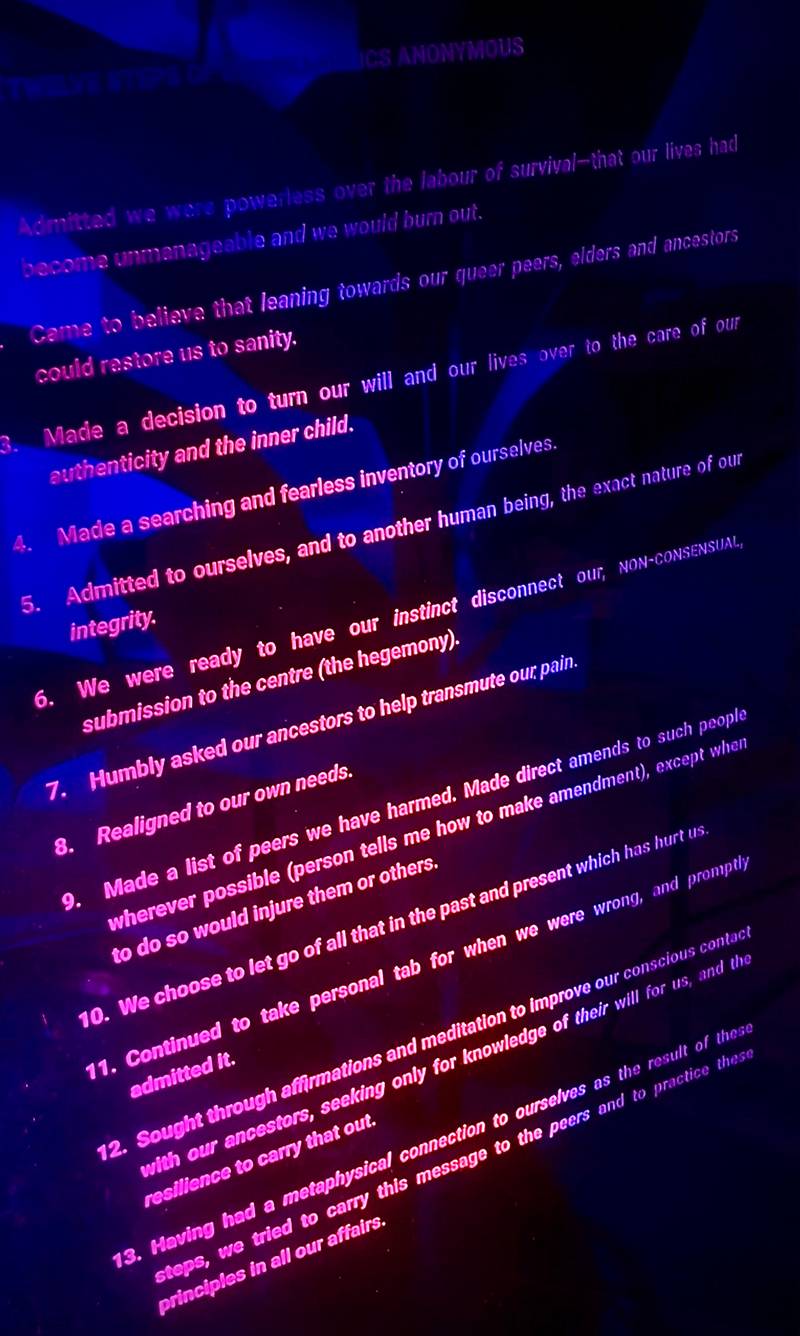

In several works, one can sense a kind of return to the basic elements of life, including (as alluded to above) water, fire, body, earth, and sound; in parallel, there are also magical religious artefacts, curses and traditional dances, meditations, amulets, and shamanic altars. Even the modified version of Alcoholics Anonymous’ twelve-step program seems to refer to magic-working – Fadescha’s ‘The Twelve Steps of Qworkaholics Anonymous’ (2023) significantly adds a 13th step (the work also serves as the main textual body of the project). The exhibition activates other forms of communication through which invisible knowledge is transmitted. This is vividly present in Michaela Dragan’s poster and audio work ‘Spell Against Fascists’ (2021) at the entrance of the exhibition and Anna Ehrenstein’s ‘The Hypnotization of the Cloud’ (2022) that invites visitors to lie down on a bed and experience a hypnosis session video through which they will be liberated from nationalist ideology.

Installation view RESONANCE BEYOND ESCAPE: QWORKAHOLICS ANONYMOUS III at NAC of Vilnius Academy of Arts, 2024, 2024. Photo: Party Office

This leads to another important visual code of the exhibition, embodied in the set design: if the mood and the setting are party-like, the layout itself resembles the structure of a religious hall and spiritual site. Similarly to religious places, the largest and most visually intense work is set at the end of the space, and its aesthetics also evoke sacrality. Noor Abed’s 20-minute film ‘Our Songs Were Ready for All Wars to Come’ enacts the mourning and commemoration rituals devised from Palestine’s ancestrality and folktales. Sacral associations are reinforced by the structure of an altar with various objects (chess pieces, flags, scraps, cards, candles, feathers) that look like an assemblage of objects washed up from the sea, victims of forced migration. Significantly, the ecological messages in the exhibition are articulated not through a didactic condemnation of the anthropocene but by experiencing nature as part of oneself. For example, through reclaiming peasant dances that communicate with the landscape and lying down on the earth (‘Our Songs Were Ready for All Wars to Come’), merging with the sea and trying to bury oneself in the sand (Pedra Costa’s video diptych) or mechanically pasting pictures of bodies into another environment (‘Show Analysis 03’ by Gabriele Gervickaite) to underline the discomfort of these situations. At the same time, bodily gestures express intense mental and spiritual processes in almost every work, and its choreography is led by historical and folkloristic motifs and references, as well as post-digital aesthetics. The exhibition also reminds us about the exploitation of nature for economic profit and draws similarities to the violence towards people from contested territories.

Fadescha, The Twelve Steps of Qworkahlics Anonymous, 2024. Photo: Fadescha

The body can be defined as the dominant medium of expression in the exhibition, with the artists simultaneously celebrating rights over their bodies and pointing to the fragility and impermanence of these rights. These are multi-contextual bodies, specific and generalised at the same time. Several works make the skin an essential medium of expression, both vulnerable and anonymous. Skin as matter, which is the physical boundary between the external and internal world, is also a tool through which people have been dehumanised historically and, unfortunately, still are. In several works, it is precisely the clothing that articulates the experience of the body – the overall black figure in the video work by Malik Irtiza that suggests anonymity and erasure or in the photographs by Rafiki where ongoing violence is reminded through the collectively produced works of veils in beadwork spelling out GA-ZA. Throughout the exhibition, a narrative of difference emerges, which isn’t easy to classify under categories – perhaps this is why the elements of impersonation and living embodiment of the other are so important for many of the authors. It reimagines different roles and images, the inability and, at the same time, the constant need to feel authentic, to recognise oneself.

Film Still, Simon(e) Jaikiriuma Paetau & Natalia Escobar, Aribada, 2022.

Rafiki, Untitled, 2024.

It would be naive to try to draw a strict line between outer image and essential nature because such divisions belong to the same categorisation process that exhibition tends to overcome, talking back to toxic, binary tropes of masculinity and femininity, traditionality and modernity. For example, the film ‘Aribada’ (2022) by Simon(e) Jaikiriuma Paetau & Natalia Escobar tells a story about Aribada, the resurrected monster, who meets Las Traviesas, a group of indigenous transwomen from the Embera tribes, and decides to join their transfuturist community. This is a visually stunning story about the intersection of the worlds of myths, utopias, and futurism where all of them are equally important. The bodies of Qworkaholics echo Foucault’s thesis of modernity as the disciplining of the body while simultaneously embodying gestures and states that represent the liberation from the body of modernity – a productive, purposeful, human-work tool in the factory that produces values of neoliberal capitalism. Instead, they immerse themselves in a world of tales, myths, folklore, everyday magic and anarchistic utopias as means of undoing neo-liberal work conditions. Being in motion, blurry, performative and processual makes runny spaces to avoid any restrictions and limitations. The bodies of Qworkaholics are quite the opposites of the modernist’s machine-bodies.

Video Still, Noor Abed, our songs were ready for all wars to come, 2021.

Video still, Pedra Costa, the lady in white, 2024. Nida, Videography by Blue Paul Flemming

The nakedness, the acts of dressing and undressing do not represent sensuality or defenselessness; it is instead a rejection of social labels to focus on a self-directed relationship with one’s own body, as in the autobiographical works of artist Blue Paul Fleming or works of Queer Falafel, exploring gender and ethnic identity. In Pedra Costa’s video diptych, the artist steps into the sea wearing a dress made of diapers that soaks with water and try to bury herself into the sand. Both gestures recall activities of extinguishing the fire, and both are physically difficult and even harmful, begging the rhetorical question of whether the struggle with burnout can ever be a pleasant and harmless action (as so many self-help advice suggest when recommending relaxing, enjoying yourself or taking time for hobbies as ways to recover). Or has the capitalist establishment been so cleverly designed that any attempt to escape it becomes a new problem, a new burden? Pedra Costa’s work illustrates this circle of external violence transforming into internal violence to which certain people are, by default, subjected simply by virtue of their origins. It illustrates how any long-term form of oppression creates a negative impression on oneself, alienates one from oneself, and creates an internally violent relationship. I consider this to be one of the most important messages of the exhibition, which should not be vulgarised to the level of self-help literature – how to unite external anarchy with radical internal self-care? Some possible answers can be found in Fadescha’s ‘The Twelve Steps of Qworkaholics’ (2023): “3. Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of our authenticity and the inner child; 4. Made a searching and fearless inventory of ourselves; 5. Admitted to ourselves and to another human being, the exact nature of our integrity.”

How is it that an exhibition that tells the story of the trauma and still active consequences of colonisation is forced to experience yet another hate attack in a country that has also suffered from occupation and ethnically motivated repression?

The stress of isolation, the lack of connection to one’s culture and community, the alienation – the fusion with nature seen in many of the works seems like an attempt to physically find one’s place and belong somewhere, to ‘grow back’ into their roots. Most works speak (or include a reference) about cultures, places and traditions from which the authors have been severed or whose belonging is threatened by distance and various racist and ethnic prejudices. Here, we must return to the context of the exhibition’s location. The NAC as a residence is also a temporary, impermanent place of refuge, which fits well with the spirit of outsiderness, exile, and migration as a way of living expressed in the exhibition. At the same time, the residence as a type of cultural institution is also a place that is neither a place of rest nor a place of work; it combines both and serves as an in-between space for both states. Several works of Resonance Beyond Escape have been made here on site. The context of the place, however, leaves the most significant mark on the exhibition – not when it was made but when it was exhibited – by the context of the place, which means local society, its history, and current political vectors.

Installation view RESONANCE BEYOND ESCAPE: QWORKAHOLICS ANONYMOUS III at NAC of Vilnius Academy of Arts, 2024, 2024. Photo: Party Office.

The reactions around the exhibition unfortunately reflect and include the outside world against which the artworks are set: the pro-Palestinian graffiti on the outside walls of the NAC building, with the flag of the Palestinian state and the words ‘from the river to the sea’, which the local Jewish community and the Israeli Embassy asked to remove, initiating a criminal case for alleged anti-Semitism, also turns into a confrontation. How is it that an exhibition that tells the story of the trauma and still active consequences of colonisation is forced to experience yet another hate attack in a country that has also suffered from occupation and ethnically motivated repression? The inheritance of these traumas, their ghostly presence in the present, poignantly illustrated in the work ‘Show Analysis 03 of the Lithuanian artist Gabriele Gervickaite, seems to have come alive in a grotesque form.

Similar restrictions on freedom of expression are, unfortunately, faced by many local activists whose creative work or personal statements criticise the Palestinian genocide. It should be emphasised that the NAC is the only art institution in the Baltics that has recently addressed the geopolitical situation in the Middle East and allowed creative freedom to express messages that support Palestinian freedom. In other Baltic countries, some short-term events in support of Palestine have been organised and have often been met with intolerance, threats, accusations of anti-Semitism and incitement to hatred. So, the aforementioned context of the venue means that Resonance Beyond Escape is not taking place in a bubble or safe space. It is not a party within a party where everyone nods their heads in mutual understanding since the Baltic art and the overall community are mostly politically passive, centre-right and prejudiced. The restrictions on the exhibition, in a sadly paradoxical way, only confirm the freedom struggles artists are aiming to highlight: as support for Palestine – the most active point of genocide today – is being restricted, Qworkaholics are experiencing yet another act of censorship, silencing and erasure. “Is recovering the objects of our ancestors from museums enough accountability for having buried them alive?” Party Office asks rhetorically in the exhibition’s accompanying text.

As Legacy Russell pointed out very precisely in the now canonical manifesto ‘Glitch Feminism’, gender has become a geopolitical territory, and the world needs radically new understandings of space, of a body, of their dynamics. The exhibition shifts the focus from objects towards the humans and lived, hard-to-categorise experiences, feelings, sensibilities and subjectivities; it manifests the need to move the decolonisation out of museums into very different, everyday spaces, realities and, of course, current times. It is a task much more difficult than relocating museum artefacts, yet much more important and meaningful. Resonance Beyond Escape can be interpreted as a micromodel of this new space, suggesting visual and physical forms that reflect and embody the actual choreography of living and sensing.

Feat. Blue Paul Fleming, Pronoїa Ep 2 – A day of Belonging (Humbolt Klinikum 2021, Athens 2021, Markisches Viertel 2023), 2024. Installation view RESONANCE BEYOND ESCAPE: QWORKAHOLICS ANONYMOUS III at NAC of Vilnius Academy of Arts, 2024, 2024. Photo: Party Office

Installation view RESONANCE BEYOND ESCAPE: QWORKAHOLICS ANONYMOUS III at NAC of Vilnius Academy of Arts, 2024, 2024. Photo: Party Office