Installation view, Bulgarian Pavillion’s exhibition ‘The Neighbours’, courtesy of Krasimira Butseva, 2024

Bayr(y)am Mustafa Bayr(y)amali (1997) is a London based (Bulgarian)Turkish visual researcher, programmer and organiser. His practice deals with issues of new world (b)orders, il/legal identities in the Balkans and beyond. He co-runs the Old Mountain Assembly – a programming space for worlding and futuring a transitional and decolonial perspectives in South/East Europe.

Founded in 1895, the Venice Biennale primarily serves as a platform for countries to showcase their specific self-image, deeply rooted in the reinforcement of nation-states and borders. Employing imperialist, extractivist, and fascist ideals of world (b)orders, the Biennale serves as a gathering place for the global cultural class. It was first inaugurated to celebrate the silver anniversary of King Umberto I and Margherita of Savoy, an imperial king who led expansion and occupation into Somalia, as well as the creation of the Triple Alliance. For the 60th edition, artists were invited to respond to the theme “Foreigners Everywhere” which is somehow ironic given its imperial beginnings.

Roaming around the city, a peculiar representation of the world was within my reach, scattered across various buildings titled pavilions, some more prominent, some on the margins. I was reminded of Daisy HiIdyard’s concept of two bodies - as part of humanity’s global presence and as discrete individuals1. In an interconnected global world, it becomes hard to come to terms with my two bodies—my body taking airplanes to attend an art festival and engage in cultural production, staring at various artworks, trying to grasp what each piece made me feel, and my other diffused body and its consequences across borders. The entanglements between these two bodies are almost unlinked, silenced and disquieting.

To write and engage in criticism, one must establish a connection between these two bodies in an effort to create a new language. Interrogating how these bodies collide calls for an examination of not only what I see with my eyes but also my embeddedness in a worldwide network of ecosystems, genocidal destruction, climate decay and death. The notes offered below are not a review of the Bulgarian pavilion but rather a provocation to work with the silences in history, to honor the past of my family, and to unearth the connection and bridges between my two bodies. One witnessing and one actively engaging in articulating my positionality in the world in relation to the notion of nationhood, identity and language, which I was prescribed—Bulgarian Turkish.

- While examining a specific positionality of Turkishness situated in Bulgaria, I acknowledge how race relations and ethnicity take different shapes and forms across borders. I see Turkish race and nationhood in a global context shaped by intransigent westernisation and in relation to the genocide and occupation of Kurdistan, Armenia, and Cyrpus and wider geopolitical colonial aspirations.

Installation view, Bulgarian Pavillion’s exhibition ‘The Neighbours’, courtesy of Krasimira Butseva, 2024

“Look, try to understand it like this: there’s a circle, a small circle. This is a primary circle. And in this circle, I put things that have accumulated through the years, things that I have not shared with anyone ever. I said them to you for the first time.

Yes, I have not shared these things with my husband. It is the first time that I speak about these things with you. Until now, I had not told anyone about anything.” … “It is because they cannot understand me. They cannot.” – Nadezhda Bozhinkova-Kasabova

The words of Nadezhda were the first thing I heard entering the Bulgarian Pavillion in a room, lights low, with a distinct scent, reminding me of the same smell I encounter each time I enter my grandparents’ house full of the 70s and 80s furniture produced in the Eastern Bloc. The installation, set up into three sections—a living room, a bedroom and a kitchen—invites audiences to sit on the couch, touch the bed, open the fridge. And to listen.

The words of survivors of political violence in communist Bulgaria from 1945 to 1989 illuminate the room, translated to English and read out loud by actors. Encouraged to move across the room by following the voices of interviewees who recall their trauma—often accompanied by a stream of details, as they revisit it for the first time - sentences flow around the space, and silence is present in between. A silence that is sometimes deafening, a silence sometimes employed for personal reservation, and a silence sometimes imposed by the regime.

In the last 35 years since the end of the communist regime in Bulgaria, a grand narrative for the recent past is often missing in history books or in public discourse. The silencing of the political repression faced by minoritised ethnic groups (such as Turkish, Roma and Bulgarian Muslims), anarchists, farmers and queer people creates a vacuum in understanding the nation-making project of current-day Bulgaria.

In the months following the fall of communism in 1989, 45 years of archival evidence were destroyed in a massive purge. The remaining files, filled with euphemisms like the official camp designation “Labor Correctional Community,” offer little understanding of what so-referred ‘re-education’ through labour entailed. Reading these records entails engaging with the language employed by the state to obscure, hide, veil and silence what unfolded in the Bulgarian gulag camp system. The multimedia installation titled “The Neighbours” by Krasimira Butseva, Julian Chehirian and Lilia Topouzova attempts to work with these silences and engage in a new language that does not pursue fixed history but where the voices of the survivors collide and bridge in a memory archipelago.

My first encounter with a museum

My relationship with language was always convoluted. The first words I uttered were in my mother tongue, Turkish, in a predominantly Turkish neighbourhood. I lived between two linguistic worlds—Turkish at home and Bulgarian outside, in public institutions, and in school. My mother often reminded me not to speak Turkish when we would go downtown. She warned that “they,” however she meant at the time, would know we were Turkish if we did. So I was silent, fearing that their gazes would recognise us for being different.

My mother’s use of language, being born in the 70s in Bulgaria, was shaped by the assimilatory policies of the communist state. In 1984, the authorities began changing the names of Turkish minority in the country in a mass campaign. The police and military were used where necessary, also leading to the confiscation and destruction of all Turkish books, newspapers, and journals from both public and private libraries (refered as the state as the “Revival Process”). Speaking Turkish or any other minority language in public as well as playing Turkish music was banned. Those who defied these rules were punished, imprisoned or sent to forced labour camps.

My first encounter with a museum in Bulgaria

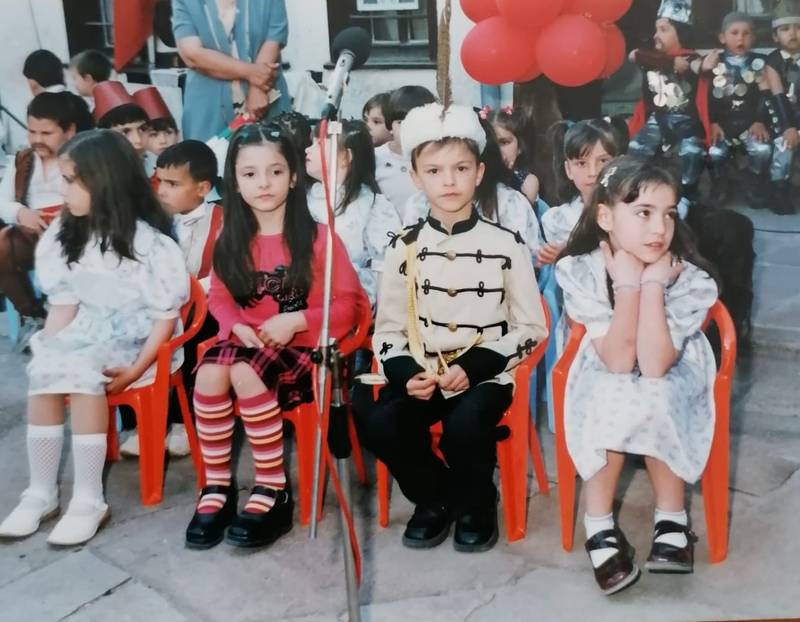

While slowly learning Bulgarian, I had my first encounter with a museum growing up in a small south-eastern town, one hour away from the Turkish border, was the House of Chorbadji Paskal in Haskovo, built in the 19th century. As my teachers were preparing the whole kindergarten to participate in a re-enactment of notable events of Bulgarian history in the form of a play with a script, we visited the Paskal’s house. We would perform in front of an audience, parents, friends, and the local community in the garden of the museum, a declared monument of national importance to culture. On our first visit, I diligently followed the museum guide, who contextualised each room and traced the transition from the traditional rural customs in the town to the urban and European customs of the local population after the liberation from the Ottoman Empire in 1889. Exposition in Pascal’s House is defined as a cumulative collection of articles on Haskovo wealthy families who lived immediately after Liberation, by the end of the 19th century. Even within the official mission statement of the museum, the idea of nation-building and nation-making through the historicization of events was apparent. My kindergarten, primarily serving Turkish children and families, exposed my peers and me to a unique historical narrative that emphasized the Bulgarian national identity, excluding any Turkishness or non-white racial and ethnic identities. The house and the museum were a testament that the land and the town, that we all grew up in were predominantly Christian with a long-lasting culture and tradition of peoples who were aspiring for a European and Christian lifestyle that resisted five centuries of Ottoman yoke.

Opened in 1971, as the first house museum in Bulgaria, it was the place where I would take on the role of the Bulgarian national hero, Hristo Botev, to sing a revolutionary song titled “Still White Danube Undulates." As we underwent two months of preparation ahead of the day of the play, I would recite the lyrics of the song, which depicts a historical event from Bulgaria’s resistance against Ottoman domination, a tale that has been mythologised among Bulgarians. On May 29, 1876, Hristo Botev led a group of 205 rebels in commandeering the Austro-Hungarian passenger steamship Radetzky through armed intervention. They utilized the vessel to traverse the Danube River from Romania to the Bulgarian regions under Ottoman rule, aiming to bolster the April Uprising. At that time, I did not understand the consequences of what my role would be in this play, nor was I able to come to terms with my Turkish identity in relation to the history telling which I was re-enacting. While embodying a national hero in the pursuit of liberation, my identity was at odds with the place I was occupying and with the character that I had to personify.

Proudly performing for what seemed like hundreds of people on that day, these events, which we were reenacting, narrated a story of a pure land of European and Christian aspirations, radical homogeneity, and devoid of any Turkish, Muslim, or Roma influences in their history and culture2.

Bulgaria as a space and a nation

While discussing the post-socialist Bulgarian space through the lens of colonial and post-colonial remains a minimally applied approach in the field of East European Studies, drawing upon reflections made by Sunnie Rucker-Chang, I believe that it is our responsibility explore the rich possibilities this might afford, rather than engage in an arguement whetherthat the post-socialist region is post-colonial3.

Bulgaria as a space and a nation had a profound impact on the way I embody myself and shaped and reshaped my sense of national identity. To this day, I remember sitting on my grandmother’s lap in 2006 on New Year’s Eve in my house, awaiting the beginning of the new chapter in Bulgarian history—our ascension to the European Union. For a country that was not a direct participant in the colonial project of Western Europe and so often described as a part of the “margins” of Europe, this geography, which I was living in, would finally be put on the world map. Or so I believed.

This also coincided with the broader whitening project of Bulgaria. Although the country’s membership in the EU or NATO did not initiate this race contract, it was not the only instance where Bulgarian culture was historicized to align with the EU-NATO race-making and imperial project. However, the expansion of the EU in the Balkans meant that this European boreland zone often described as colourblind and raceless was now re-established as a locality for walling whiteness.

Debates around a demographic threat, echoing the previous discourse seen during the the rise of entho-nationalist assimilatory policies pursued by the communist state, emerged on the Bulgarian national stage as the EU lifted work restrictions on Bulgarians. Coincidingwith an exodus of highly skilled Bulgarian workers and a general decline in birth rates, this accentuated the decades long population drop. With the arrival of Syrian and Afghan refugees passing through the Balkan route, political parties began stoking fears of “de-Bulgarianization,” manipulating selective data to highlight the growing presence of Muslim, Roma, and Turkish minorities alongside a decrease in the white Bulgarian population. In the media, intellectuals warned that the refugee influx and rising minority numbers would render Bulgarians an “extinct exotic minority,” often framing the image of refugees entering the country as a “new Ottoman invasion.” At the same time, the prime minister, who had previously praised vigilante border patrols claiming to defend Bulgaria and Europe from refugees, pledged to complete the construction of a fence along the EU’s Bulgarian-Turkish border.

These vernacular and oral forms of history enabled me to narrate what my family faced as they were growing up and how they were forcefully displaced from their homes and sought refuge in Turkey in 1989. The school curriculum did not include a retrospective of the crimes committed by the communist regime until the very end of my high school years.

Piro Rexhepi, in the book ‘White Enclosures’, explores the overlapping postsocialist and postcolonial border regimes along the Balkan Route, which reinforces regional racialized relations of power. The EU’s contract with state-owned Israel Aerospace Industries and Israel’s largest private arms manufacturer, Elbit, to develop a comprehensive drone surveillance system situates the region in a complex interlacing of global racial borders. This surveillance system employed to track migrants along the Greek coast and the Bulgarian-Turkish border leverages their effective use in the ongoing siege of Gaza. Locating the Balkans as a space walling of whiteness enables us to see this geography not as a ‘periphery’ and devoid of agency, but as an integral part of walling off whiteness3.

The border, which now signifies the epitome of the asylum-industrial complex of the EU, was once the same border that my grandparents and parents passed in 1989 during the forceful expulsion of half a million Bulgarian Turks (referred by the state as “The Great Excursion”).

Growing up, unaware of the historical context and the repressions faced by my family, in a neighbourhood surrounded by my family members, my parents would often invite our relatives for various celebrations and get-togethers in our home. Every once in a while, they would refer to each other with their Bulgarian names, or rather, their official governmental names, during the communist regime as a way to poke fun at each other. When I encountered such exchanges, I was perplexed as to why I didn’t have a Bulgarian name, while they had two. Did they have the ability to switch between their Turkish identity and the newly created Bulgarian one under different circumstances, or did someone impose it upon them?

My first understanding of the assimilation process and ethnic cleansing of Bulgarian Turks—ethnically Turkish people in Bulgaria—was first shaped by my relentless questioning of the experiences of my family in the 80s. These vernacular and oral forms of history enabled me to narrate what my family faced as they were growing up and how they were forcefully displaced from their homes and sought refuge in Turkey in 1989. The school curriculum did not include a retrospective of the crimes committed by the communist regime until the very end of my high school years4. Even in that instance, the history books did not include more than an abstract detailing what minoritisied groups or political dissidents faced under the repression of the communist state or emplyed the langauge used by the communist state to describe these events, either as a national revival or a voluntary excursion.

The past was silenced.

‘The Neighbours’

Krasimra, a friend of mine and one of the artists, offered to open the exhibition space of the Bulgarian pavilion for me so that I could see it during the night with no other visitors there. The words of Ibrahim Kadriev, a Bulgarian Turkish political dissident who underwent the assimilation process in communist Bulgaria, were echoing around the room. And echoing through my flesh and bones. And so the crimes committed by the Bulgarian regime towards the Turkish, Roma and Bulgarian Mulsim communities were often silenced; these silences started to unmute themselves slowly at ‘The Neighbours’—in the Bulgarian Pavillion.

The collaboration between Krasimira, Julian and Lilia, an installation displaying objects found on the streets, stones, water and plants retrieved from camp sides around Bulgaria, was away from the main pavilions at the Bienalle, beyond the Giardini and the Arsenale. A labour of long research has resulted in the opening of the first version of the exhibition in the studio in 2022, where most of the installation was created. The project was not initially conceived as a project to represent Bulgaria in Venice. Rather, it opened at St. Georgi Benkovski 49 Sofia, Bulgaria, with hundreds of friends, collaborators and people who have heard about the show from relatives, the media or from the posters across the city.

Installation view, Bulgarian Pavillion’s exhibition ‘The Neighbours’, courtesy of Krasimira Butseva, 2024

Installation view, Bulgarian Pavillion’s exhibition ‘The Neighbours’, courtesy of Krasimira Butseva, 2024

The different spheres within which the politics of memory, either through public institutions or cultural practices, where narratives are forged, rarely come into direct relation with one another. In the context of Bulgarian historiography, the link between the two is further severed due to the inaccessible documents and artefacts in the national archives. As a result, the three collaborators take on various roles of ethnographer, historian, artist, witness, filmmaker, and collector of testimonies. Instead of offering a grand narrative of the communist past, the installation seeks to confront who writes history and who is allowed to be remembered.

For Daniela Koleva, the Bulgarian memorialisation of the past is unfinished, unreconciled in the form of “a discursive archipelago wherein the islands are isolated from one another, with incomparable ethics and irreconcilable versions of the past, each of them engrossed in the collective production of historical innocence”5. The inability of the state to atone for the crimes committed in the recent past, specifically the (mis)attempts of legal and extra-legal restorative justice, in the face of human rights violations in communist Bulgaria, allows numerous vernacular and institutional versions of memorialisation of the past to exist and not be connected across various islands of memory archipelago.

Approaching memory as a cultural practice favours for these islands of diverging remembrance of to come into together. Some inhabiteded with individual act of remembering and understanding, some with a post-communist nostalgia, and others with institutional memorialisation, are brigding into an archipelago of the recent past. Working with oral histories and collecting against the grain, ‘The Neighbours’ attempts tothrough the silences, everpresent in language and memory, silences that offer a link between those who are forgotten, unseen or invisible. The past becomes unmuted, and somewhere there is memory being shaped between the utterance of words and the sounds before each letter.

I meet Krasimira for the first time at Waterloo Station in London. We find a spot on the grass next to the London Eye and begin discussing our research. A man sitting across from us overhears our conversation. Just as we are about to leave, he approaches and says, “I hope I didn’t disturb you. I missed hearing others speak Bulgarian.” Krasimira and I exchange a glance.