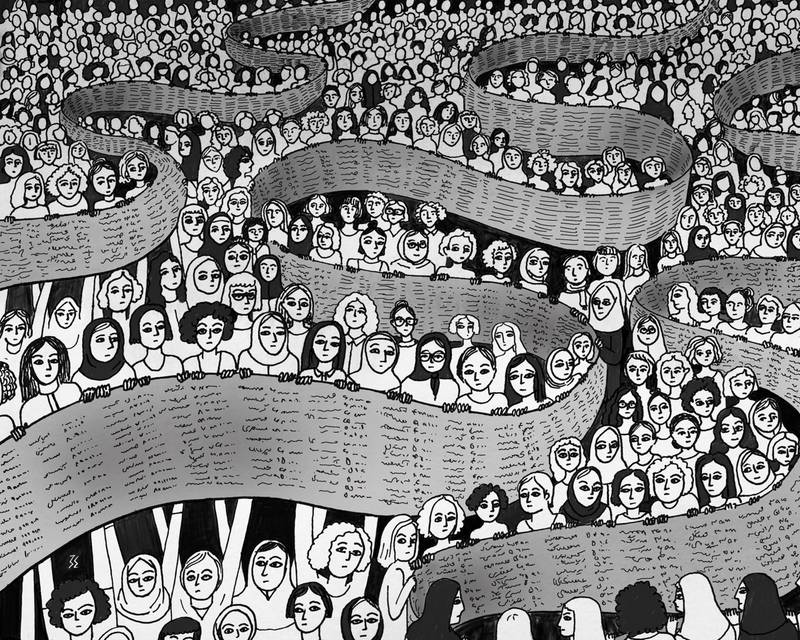

Illustration by Hajar Moradi

Niloofar Golkar is a Toronto-based activist. She was part of the feminist movement in Iran and moved to Canada in the summer of 2008. Since she has been active in environmental resistance and labour movement, she has also been a course director in politics and global studies.

The One Million Signature Campaign started on August 27, 2006. I’m writing this reflection eighteen years later. Since then, a few uprisings have happened: the 2009 Green Movement against a fraudulent election, the December 2017-January 2018 uprising against poor economic conditions targeting President Rohani’s government, the “Girls of Enghelab” protests against compulsory hijab, the 2018-2019 nationwide general strikes against a sudden surge in fuel prices, and the more recent 2022 “Jin Jian Azadi” movement. This reflection is an attempt to put the One Million Signature Campaign in the conjuncture of rapid and dynamic politics from these movements and the conservative theocratic ideology of a state unwilling to change.

In 2006, I was a Tehran University student interested in activism and feminist ideas. I went to a gathering that was supposed to happen in the Raad Institute space in Tehran, an event that would mark the beginning of a Campaign to change discriminatory laws against women. When I got there, I saw people, including some well-known feminists, writers, and intellectuals, chatting on the street. I asked someone where the event was, and they responded that authorities prevented it from happening inside the salon, so we are gathering signatures on the street here. Day one of the Campaign was a testimony to the rocky path ahead and the resilience of its organizers and participants. I joined the One Million Signature Campaign, a feminist movement with a bottom-up approach.

The campaign specifically targeted laws that predominantly affect women in the family and domestic spheres. Discriminatory laws included those governing marriage and divorce. For instance, the age of criminal responsibility for children, which allows for child marriage, grants men the right to divorce and practice polygamy in most cases. This makes it nearly impossible for many women, especially poor, working-class, or rural women, to escape abusive marriages, as they often lack access to safe spaces and adequate income after divorce.

Other discriminatory laws involved monetizing the value of human life. In cases of injury or death caused by another person, the guilty party must pay twice the amount for a male victim as they would for a female victim. In legal proceedings, the testimony of two women was considered equal to that of one man, and in some cases, women’s testimony was not accepted at all. Inheritance laws stipulated that daughters would inherit half the amount given to their brothers, fostering power imbalances and conflicts among siblings. Additionally, laws granted husbands or fathers the right to control whether women could work or travel.

Custody laws, which awarded custody of children to the father or paternal grandfather after a certain age, created numerous unjust and violent situations for women seeking divorce or, in the case of a deceased father, left them in despair over losing custody of their children. Since these laws were deeply embedded in everyday life, they became frequent topics of discussion for campaign activists, who raised awareness by talking to family members, strangers on the bus, or people in parks. You can imagine how heated those conversations could get, and many times other women would jump in and ask to sign while others would refuse to sign the petition.

Radical or Liberal? Islamic or Secular

The one million signature campaign was significant in its process, which included action intertwined with knowledge production and consciousness-raising. It forced people, especially women, to engage in conversations and actions about their rights. Through this process, we expanded consciousness and culture about equity and anti-oppression feminism, which went beyond equal rights. This process brought up many conversations within the Campaign about different forms of discrimination that are connected, such as the right of ethnic communities to speak and teach in their mother tongue, empowering women, economic situation, and meaningful conversations around power relations between various social groups in society, but also within the struggle and movement. — Parvin Ardalan

The face-to-face method put many of us and other people outside of our comfort zone to have important conversations with our families and with strangers on the street. Some of these conversations break the stereotype of who might support women’s rights and who might not, as we found passionate allies in all different social groups, classes, ethnicities and even religious allies.

The movement was street-based, using a face-to-face method, which became its biggest strength—but it also created an expansive umbrella with people with different beliefs and backgrounds to join. The core people who started the Campaign were primarily secular: some leftists, intellectuals, writers, journalists, and activists from the Women’s Cultural Center and Zanestan Magazine, an online feminist journal. Many had years of experience that brought into organizing the campaign, a valuable social resource. However, the main body of the campaign also included many without prior experience but were very enthusiastic and full of energy.

Members used mixed methods such as art, writing, and workshops alongside taking over public and private spaces to gather signatures supporting the changes. But it also sparked many conversations, actions and reactions that spread consciousness about women’s issues and rights in society. The face-to-face method put many of us and other people outside of our comfort zone to have important conversations with our families and with strangers on the street. Some of these conversations break the stereotype of who might support women’s rights and who might not, as we found passionate allies in all different social groups, classes, ethnicities and even religious allies. That experience taught me a lot about organizing and the connection of different forms of oppression to each other.

The Campaign was easy to join, which became one of our strengths. Whoever would want to join and gather signatures could attend a workshop that had three sections of general info about the history of the Campaign, followed by a legal section where a lawyer would talk about specific laws and the legal arguments and counterarguments around them, and the third section, which would teach about face-to-face and street outreach, how to stay safe if targeted, and more. These sessions would be organized by a workshop committee. There was a list of those who could provide their homes as workshop space and a list of facilitators for each section of the workshops. The workshop committee members would call the lists and confirm the time, space, and facilitators. Then, they would call those who wanted to attend the workshop to see who was available for that specific time. At the peak months of the Campaign, we had workshops every week, sometimes two or three workshops a week. All aspects of organizing it were volunteer-based, which needed lots of commitment, enthusiasm, discipline, and hope. If a group of people in another city contacted us and asked for a workshop, a group of facilitators would travel to those cities, and they would start a branch of a campaign there. The movement became big quickly and expanded to many cities.

Women led each campaign committee from different communities; many did not have prior experience in organizing but found a space in the Campaign to come together with many other women facing similar issues. People from different classes and different world views have been experiencing injustice, discrimination and violence in the name of law, religion and tradition, and many women were saying enough is enough.

Our Campaign grew over different regions of the country. It became one of the most successful organizing efforts since the period of political stagnation caused by the political arrests, executions and exiles of tens of thousands in the 1980s. The reason for expanding so quickly and widely was not coming only from methods of organizing but also from the excessive need to break the oppression within the society. Women led each campaign committee from different communities; many did not have prior experience in organizing but found a space in the Campaign to come together with many other women facing similar issues. People from different classes and different world views have been experiencing injustice, discrimination and violence in the name of law, religion and tradition, and many women were saying enough is enough.

The committees were an essential force behind the Campaign. They were all volunteer-based, and there were many meetings to bring everyone on the same page. Volunteers could move between committees and take on different roles, which was empowering for many people. That became a key to the Campaign’s continuation, as skill sharing would allow the committees to stay functional even when some members would get arrested. It was practicing more horizontal organizing, so there would be no specific person that authorities target and could stop the campaign.

One of the most interesting initiatives was the street theater working group, which transformed discriminatory laws into various play scenarios performed in public. In these performances, for example, two or three campaign members would pretend to be family members engaged in a heated argument about one of the laws. You can imagine how such an intense “family” conversation about these issues would quickly draw a large crowd. Each person in the crowd would have an opinion and take sides. Other campaign members, in the crowd, would guide the emotions and conversations toward women’s rights and how discriminatory laws contribute to family problems. At the end, a member would begin gathering signatures, and then everyone would disperse.

These methods, besides protesting and street face-to-face talking and gathering signatures, were necessary to undo the normality of discrimination and patriarchy. The one million signature campaign brought a reviving soul into Iran’s feminist movement and civil society by bringing the challenge to homes, families, streets, and every public space, such as buses, parks, and workspaces. Face-to-face conversations would bring deep conversations, many personal stories and many more people to join the movement.

Many analysts and writers might have tried to reduce the Campaign to a right-based liberal feminist movement, but that is a very simplistic analysis. Liberal movements use lobbying and compromise their goals in the face of power. The Campaign was constantly reaching more hidden aspects of discrimination against women in the face of political repression. Although the Campaign stopped before reaching its goals due to oppression and imprisonment of its members, censorship, and threats, organizing for prisoners rights, and shedding light on some of the most brutal stories of women imprisoned and in line of execution became another effort. Because of its bottom-up approach, people who shaped the Campaign would create many radical processes that expanded to place-based empowerment initiatives of women for women, self-sufficiency, and organizing against execution and prisons.

The liberal or state-friendly argument was used to create division between the feminist movement and especially the workers movement. The Campaign started after the first year of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s presidency, who represented a new brand of conservatives mashed with Islamist nationalism that enforced the militarization of the economy under the brand of privatization. Religious fundamentalism, nationalism and militarization of the economy are all known threats to women’s status and rights in the same way that intersectional feminist movements are a threat to any form of authoritarianism. But at the same time he was cutting subsidies and cracking down on organized labour. The anti-labor and anti-women’s rights policies were complimentary. For example, while Ahmadinejad’s government was trying hard to join the global trade and implement International Monetary Fund (IMF) measures, part of its ideological strategy was to promote larger families. He was hoping to create forced measures on women’s bodies to keep reproducing children. The hope was that, after joining the global market, Iran could provide a cheap workforce for international corporations willing to invest in the country. Part of that plan was the brutal suppression of the workers’ movement and major independent unions.

However, except for a small fraction of the workers movement who were eager to collaborate and work together with the Campaign, the majority dismissed its issues. Either with the claim that the campaign is too liberal or economic issues are more important than women’s issues. The claim unfortunately surfaced in the first years after the revolution, when women’s rights were under attack.

Women’s oppression is not in a vacuum separated from other forms of oppression faced by queer communities, religious minorities, people with other ethnicities, and the working class, as systems that reproduce oppression do not just target one group. They create a hierarchy of power that includes different forms of subjugation, oppression, discrimination and exploitation. Although Campaign was targeting mostly family laws, those discriminations had deeper roots in the economic and political life of women in Iran, such as restrictions on taking on positions of power, gender apartheid in some jobs, and forced hijab. The discriminations and patriarchal culture that have been confronted by a long history of feminist and women’s rights movements for hundreds of years. At the same time, the limitation of women from public spaces and positions of power was imposed by the restriction of women from taking specific jobs. Forced Hijab, however, brought limitations in public space and produced daily systematic, organized violence at the hands of police and Basij paramilitaries against women on the streets for not covering enough.

Waves of arrests of many feminists, including myself, by state intelligence forces were an attempt to stop the successful rooting of the feminist movement. Ironically, feminists facing arrest opened the world of prisoners and brought the interrelation between the subjugation of women and incarceration to the forefront of our thinking and actions.

Like any other movement, we also had tons of internal conflicts and issues that needed to be unpacked as a group but also as individuals. The campaign method was to target these oppressive layers and create a culture of resistance similar to the workers’ movement, Kurdish movement and student movement in Iran but also promote and ignite “cultural politics,” as patriarchy and women’s oppression are usually separated and represented as a form of culture and tradition. Breaking those lines brings women’s issues to the political and economic realm, which is not separated from reproductive and subsistence work that supposedly happens in the private sphere of the home. These initiations empowered women, turning the suppressed subjectivity that the state has been trying to pose upon women since the revolution into active subjectivities and, in many cases, rebel subjectivities backed by communal struggle.

The effect of the Campaign was also visible in our demonstrations. I remember the number of people in meetings and demonstrations increasing from dozens to hundreds in a year. In the beginning, the public did not show much interest in our messages, but as the Campaign continued and expanded, sometimes random pedestrians joined the demonstrations or gave positive comments. The state also noticed the popularity of the Campaign and started the arrests and police brutality in the demonstrations.

Waves of arrests of many feminists, including myself, by state intelligence forces were an attempt to stop the successful rooting of the feminist movement. Ironically, feminists facing arrest opened the world of prisoners and brought the interrelation between the subjugation of women and incarceration to the forefront of our thinking and actions.

I always think about those consequences when you challenge the power hierarchy of a dictatorship that has developed a system of identities, laws, and so-called ethics that are intertwined with economy and social status. The consequences are harsher, and such a system repeats the brutality to suppress generations of activists and communities. In an oppressive dictatorial state, it does not matter who you are or what you do; if you are not part of the inner circle of the elite, anyone may face an unjust situation. That was why the killing by the so-called morality police of Jina Amini, a 22-year-old woman from Kurdistan who travelled to Tehran with her family, sparked a feminist uprising in Iran in the fall of 2022.

The right of freedom of choice in clothing was not part of the Campaign’s demands, as the Campaign began from point zero of women’s demands, and state violence around the hijab was high. However, many of us talked about the violence of forced hijab and the right to freedom of choice of clothing and wrote about it on our websites, such as Zanestan, an online feminist magazine. Policing women’s bodies in the most brutal way of kidnapping women on the streets by the so-called morality police, being fined, humiliated, and jailed was a reality for thousands of women on the streets of Iran.

The takeaway from this condensed short history is not to feel sad but to realize movements continue, even when the harshest defeats happen. Sometimes, they continue openly on the streets; sometimes, they continue underground with coded art pieces and writings, and the continuity of it can cause a revolution. None of us thought that one day millions of people in Iran would come to the streets under the banner of ‘Jin, Jian, Azadi’ to protest the violation of the rights of women, and women would be at the forefront, burning the symbol of their oppression. I see that as success, even though there is a long, hard way ahead to shift the power relations of society. We need to keep burning symbols of our oppression long enough so that they burn the pillars of oppression and dictatorship.