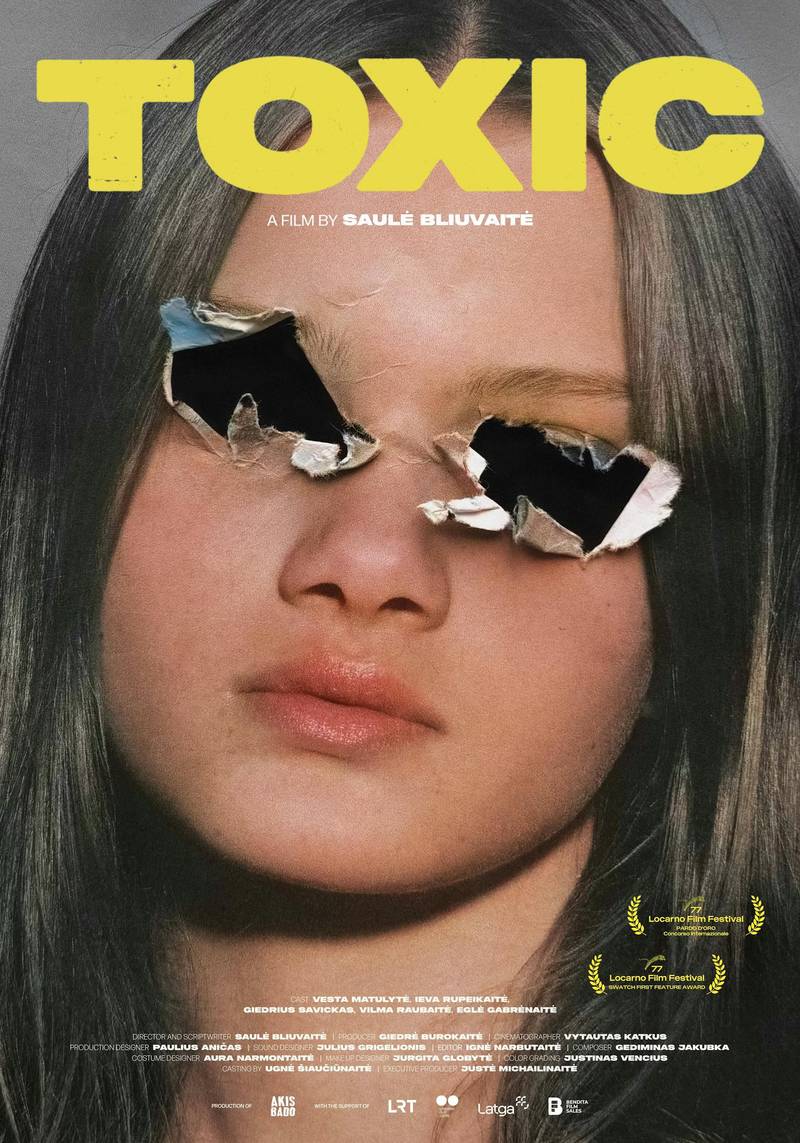

Official poster for the film Toxic, 2024

Valentina Černiauskaitė is a Lithuanian visual artist and storyteller currently based in Helsinki. Her practice is situated around recurring themes and phenomenon of time, memory, human relationships and fragility. Often stemming from personal recollections, Černiauskaitė’s work lies within the intersections of drawing, images, installation, publishing, and writing.

September is a blissful month for many things, yet a highlight among them is indeed the Helsinki International Film Festival – Love & Anarchy. That is, if you are into films and based in Finland, and so am I. Among this year’s program’s over 130 feature-length films and nearly a hundred shorts, I found Toxic at the very top of my list. I believe the case is not only due to the fact that it’s coming from Lithuania—my home country—but also because it suggests yet again that another coming-of-age movie can be much more relevant to audiences outside of adolescence than one may expect.

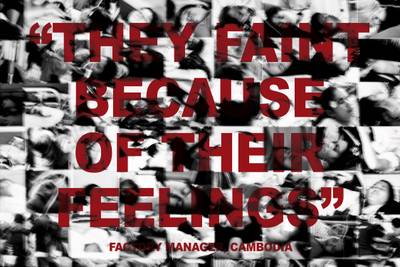

Saulė Bliuvaitė’s debut feature Toxic, the winner of the Golden Leopard at the 2024 Locarno Film Festival, takes the audience into a setting that, at first, feels rightfully distant—the gloomy outskirts of Kaunas, caught in the remains of its industrial past. The viewers find themselves immersed in a place that stands in limbo—between past and present—yet filled with the dreams of young people yearning for something more. With dynamic cinematography by Vytautas Katkus and haunting music by Gediminas Jakubka, the film encapsulates the unsettling intersection of ambitious dreams and reverse reality. Through its muted palette, cold light flowing through cracked windows, well-timed camera glides across vast, empty spaces and sharp depiction of everyday life, Toxic stretches into the shadows of adolescence, highlighting the turbulence, the impatience, and the quiet desperation that many experience in their teenage years.

The story centres around Marija (Vesta Matulytė) and Kristina (Ieva Rupeikaitė), local girls who struggle to connect and to be seen but soon are bound by a shared desire to escape their given circumstances. Marija is dropped off at her grandmother’s home by her mother, who is hinted to live abroad. Born with a limp and coming as a new kid in a grinding neighbourhood, she is destined to draw unwanted attention from her local peers. After Marija’s first day at the swimming class, one of the local girls steals her jeans. Swearing, violence, fights, and name-calling greet the audience in the very opening scene, presenting the means and methods of how to survive in a given context. Soon after, Marija is forced to play by the street rules and handles her first tryout by confronting Kristina and, ironically, through an outburst at a street fight, winning her respect. The duo bonds at the modelling school—a dangerously shady yet the only local pathway to a brighter life for the native youth. Here, as the teacher states, the girls learn to perform confidence and adopt poses and expressions that mask their insecurities—a bittersweet mimicry of adulthood that, with a stroke of luck, may take them to a place far away. The school becomes a synonym of a future and a mirror of their real or imagined flaws, a place that has been wisely chosen by filmmakers as a ground where unfulfilled promises, hope, desire and societal expectations meet.

Toxic mirrors the spirits of a society learning to navigate freedom while haunted by an unresolved past. Here, the idea of the West glimmers like a distant oasis—a place of glossy dreams and bright promises that never quite materialise, as for many, those dreams soon meet harsh reality.

The film runs through a handful of deeply intertwined strands: children who are left to navigate fragile teenhood years on their own, friendships that fill up the lack of parental figures, an effort to try and build one’s future no matter the cost, choices driven by the need to fit in, toxic environments that in no time become one’s beloved home, and societal norms that shape and give context to the whole picture. The film succeeds at raising questions beyond the characters’ struggles, calling out to the viewer with the faint echo of shared experience. What is this ache to be seen, to belong? Where does the search for beauty end, and the bruises of self-doubt begin?

In Toxic, friendship and rivalry weave together in a complex dance, an intricate play of support and silent competition. Filled with both violence and tender moments, in the film it emerges as a fragile lifeline. Through Marija and Kristina’s relationship, Bliuvaitė explores the delicate balance of support and dependency, a bond that deepens but remains undefined, residing somewhere between friendship and romance. The plot is built around the dynamics of their interaction and plays with the differences of girls’ characters—naturally shy Marija and bold and dominant Kristina. The girls move together through pain and joy, building a sanctuary in each other’s company. Yet, beneath the comfort, lies an unspoken tension—a haunting awareness that their dreams might take them on diverging paths or perhaps lead nowhere at all. This tension is the essence of Toxic: a constant push and pull, a dance of intimacy, ambition and despair.

Film still, Toxic, 2024

The screenplay is carefully set within a framework of contrasts: childhood and adulthood, safety and danger, stillness and action, love and despise, lack and abundance. The latter one wraps around many storylines, and among them, a lack of parent figures, that naturally creates a thriving space for an abundance of influences from peers, misbeliefs, stereotypes and social pressure. Parent figures here are both present and invisible, with most teenagers’ day-to-day life passing by without their notice. Yet when the moment comes, a grandmother of Marija treats Kristina and offers her a helping hand when there’s no one else to turn to—and essentially, her on-the-verge-of-witchcraft traditional medicine spares a life. A couple scenes back, Kristina’s father sells his taxi—the only source of the family’s income—so his daughter would be able to secure her spot in the modelling school. As the father hands the money in a rundown local bar that happens to be something between a kiosk and shipping container, he gives a piece of self-reflective advice, asking Kristina to do anything she can in order to get out of the hell hole their lives are currently in. The picture highlights a wicked proximity of being so close yet so far to your own family, a narrative that is painfully recognizable to many of those who were born and raised in the 90s Lithuania. After the Soviet Union walls have crumbled, countless numbers of parents have left to the West in search of a better tomorrow, eventually leaving their children at the care and mercy of grandparents, who at the time had very little understanding of the reality, needs, wishes and struggles of young people in a rapidly changing country.

To truly grasp the film’s atmosphere, it’s essential to look back on the socio-economic landscape of Lithuania in the 1990s—a nation freshly liberated from Soviet rule, in the face of a new and uncertain era. Following independence in 1991, Lithuania embarked on a breakneck transition to a free-market economy, accompanied by economic upheaval, inflation, and class differences. Toxic mirrors the spirits of a society learning to navigate freedom while haunted by an unresolved past. Here, the idea of the West glimmers like a distant oasis—a place of glossy dreams and bright promises that never quite materialise, as for many, those dreams soon meet harsh reality. A narrative around modelling school represents an illusory gateway to the West—a reflection of the era’s pervasive belief that the Western world held the answer to self-fulfilment. Yet, the visual language and the mood of the picture suggest a soon-to-be-discovered disappointment of the mysterious West as a universal cure.

Safety and danger is another running stitch throughout the whole film length. A growing up phase that seems to naturally call for abundance of attention, fragility, care and love is met with the harder-than-life realities of a street life. A vulnerable time that is filled with first times—first friendships, first decisions, first mistakes, first kisses, first fights—are also filled with danger and a daily need to prove oneself. Two main actresses convey this in a captivating manner by navigating a large spectrum of emotions and actions committed by their characters. A roller coaster of their everyday life reminds of the flowers growing through the concrete, raising wonders on what keeps us going even through the darkest, deepest times, carving a path of admiration and sympathy for the main duo of the picture.

Courage is called to action as each scene approaches; from ten seconds Kristina is given to decide if she is up for piercing a tongue in the dirtiest bathroom ever seen to eating a tapeworm in order to pass the standards of the modelling competition. Choices, sacrifices and will build a world that only a few can really endure, and the only thing that seems to come to help is courage—the exact same thing that drives the characters to make sore and cruel decisions. The interesting thing about this world is that it does suck you in, and the more you fight, the deeper you sink. At first, Marija is terrified, yet with time she builds her map of relationships and reality, no matter how harsh the setting, and when her mother tries to take her back, she would rather die than leave. Her story feeds into the essential life force of a growing person—a need to find something, someone and somewhere to relate to, even if it is a wasteland.

The film critiques the absurdity of a world that pushes young girls toward perfection while simultaneously feeding on their insecurities. This paradox—the idea that one must sacrifice oneself in order to attain an ideal of selfhood—is what makes the film resonate beyond its immediate setting, touching on themes that are universally relevant. Beneath the outlines of the script lies a powerful exploration of ambition, body image, and the not-so-subtle violence society inflicts on young people, particularly women. Bliuvaitė’s semi-autobiographical touch is evident here—through her own experiences, she paints a portrait of adolescence that feels intensely personal yet universally recognizable. The urge to conform, to mould oneself into society’s expectations, is portrayed not as an external imposition but as a deeply internalised struggle. The girls face a quiet kind of violence, not through physical harm but through the relentless pressure to attain an impossible ideal. In their quest to belong, they find themselves forced to abandon pieces of their true selves.

While Toxic is essentially and primarily about teenagers, its themes reverberate far beyond adolescence, speaking to anyone who has ever felt the need to belong, to be seen. The film’s exploration of identity, belonging, and the quiet toxicity of societal expectations transcends age and time. What does it mean to be enough? How far would we go to fit in, to be loved, to find acceptance? The film invites us to reflect on our own compromises and the ways in which we, too, shape ourselves to meet others’ expectations.

Time is another complex issue at hand. Visual landscapes, linguistic subtleties and cultural context hints to 90s Lithuania—a setting of a country still echoing with Soviet occupation, yet smartphones and dark nets join the picture. At first glance, this might seem like a mismatch, yet as the film goes on, it does prove to be a director’s choice, turning towards another question of how much the setting, the environment, the socio-geographic landscape of Lithuania has changed? Is it only a tale from thirty years ago, or may there be connections, equivalents and similarities that speak to the current youth?

Film still, Toxic, 2024

The term ‘toxic’ seems to have been chosen without a mistake. Stemming from the Latin toxicus, meaning ‘poisoned’, the word implies harm, damage, and a slow, often unseen danger that permeates one’s surroundings. In Bliuvaitė’s film, toxic isn’t just an adjective describing the environment but an overarching theme and an atmospheric condition, taking over relationships, ambitions, and self-perception. This toxicity appears in the whole spectrum of its corrosive forms, from the subtlest to the harshest manifestations of a desire to belong that becomes self-destructive, a pursuit of beauty that inflicts quiet harm, and a community that fuels insecurity rather than offering support. As the feature time runs, a sense of hopelessness finds its way through. Efforts and actions teamed up with a goal of a better life appear indistinctive, like a horizon that always recedes, leading to false hopes. With no choice left, the audience starts to notice the toxicity running deep down in every angle of the story, with each of its elements contaminated, nothing left untouched. In contrast, young people on the screen absorb their environments almost unconsciously, unable to see the damage until it’s too late. The toxic landscape isn’t just physical or external; it’s a condition and psychological terrain that manifests through relentless social pressures and expectations. Bliuvaitė’s debut gives life to the term, asking viewers to confront the harmful forces we take in and, often, unwittingly pass on to others.

In the end, Toxic is not exactly a film that provides answers. Instead, it leaves us with an open-ended story, a painful invitation to ponder the present and future of young people growing up in unforgiving circumstances every day, and essentially, our own relation to them. Bliuvaitė’s work presents a sharp, violent and evocative exploration of adolescence but refuses to conform to neat conclusions. It challenges viewers to sit with discomfort, to question, to linger in the ambiguity. It offers a fresh gust of wind in a blooming age of Lithuanian cinema, paving pathways and setting stones for often overlooked voices, experiences, realities and stories to be told as they are—raw, fierce, untouched.

As the credits roll, the viewer is left with an image of two girls, not quite women, not quite children, standing on the verge of adulthood. But also, the viewer is left with a shared experience, a glimpse, a dip into their journey, their hopes and fears, and the scars of a generation that has grown up in 90s Lithuania, a world both promising and hostile. At a broader level, Toxic invites viewers to question the very nature of ambition and the cost of achieving one’s dreams, becoming a reminder of the compromises we’ve made and the pieces of ourselves we’ve let go of in the pursuit of success, beauty, and acceptance.