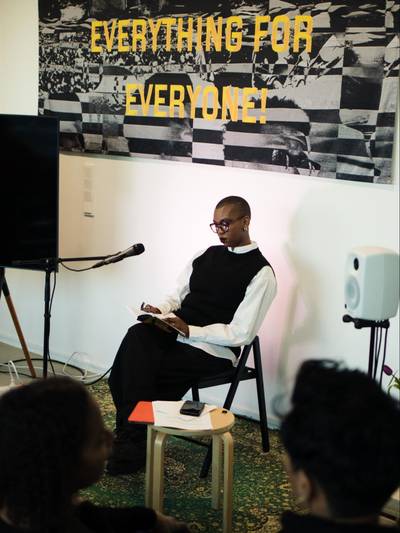

Joel Slotte at Anhava Gallery. Photo: Clas Olav Slotte

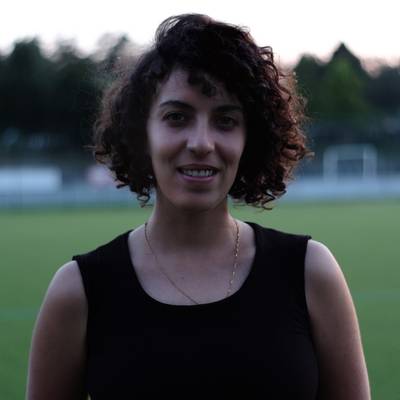

Eero Karjalainen is a critic and art historian based in Helsinki. In his writing Karjalainen has focused on topics such as the ecologies of art history, museum collections, criticism as collectivity, and contemporary painting. Karjalainen has also initiated exhibitions in Finland and internationally.

How to transform smell through a painted picture? And what ethical questions are at hand when depicting a friend in a picture? Joel Slotte has, in the past decade, developed a style of painting that reminds of numerous pop culture references and recognizable aesthetics which has been called “slotte-like” and ”slotte-esque” in Finnish art criticism. As an artist, Slotte works across drawing and sculpture in addition to painting, as the different mediums emerge in surprising ways.

EERO: I am glad that we are now discussing your practice, because I have thought, as early as 2021, when you were awarded the Young Artist of the Year award, that I would approach your works by writing and language. The same idea also emerged at your latest exhibition in Galerie Anhava. There may be references in your works that I am certain I do not recognise and, at the same time, very clear references, for example from pop and art history. It would be interesting to hear at the outset how you work specifically with paintings: how is the process?

JOEL: The process is both slow and fast, and I could start with its faster side, drawing, with which I work in a sense without censorship and erasure. I am aware that in drawing the physical mark of the work is visible to the viewer: by drawing the viewer is more difficult to deceive than by painting. In general, the themes in my drawings are more filtered than in paintings, and they contain, for example, goblins and characters familiar with fantasies and different mythologies.

In painting, the process of thinking and development is much longer than in drawing. I usually write an idea open on a sketchbook or my phone notes. With painting, I start expressly with text, writing short notes or stories, and wonder where this image came from and what could still be attached to it. For example, if the painting is a portrait – of which there were many in my latest exhibition at Galerie Anhava – the process might start with the different traditions of portraiture.

I am aware that not all references in the works are clear. I also think that in general, if we think about references and symbols in, for example, medieval paintings, the viewer does not recognize everything that the artist points to – they are forgotten.

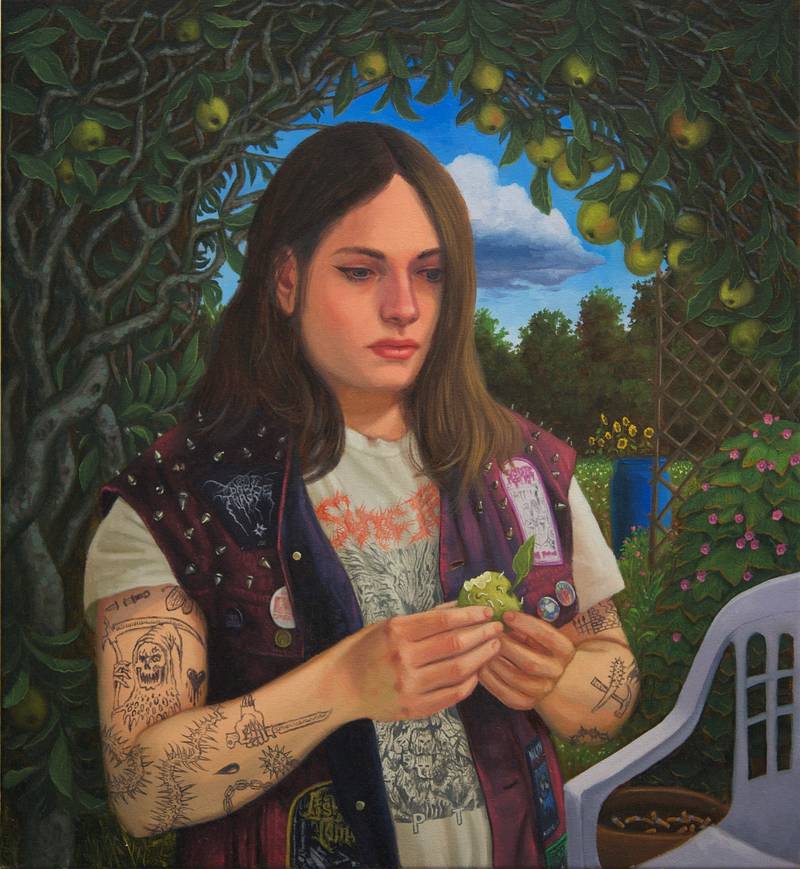

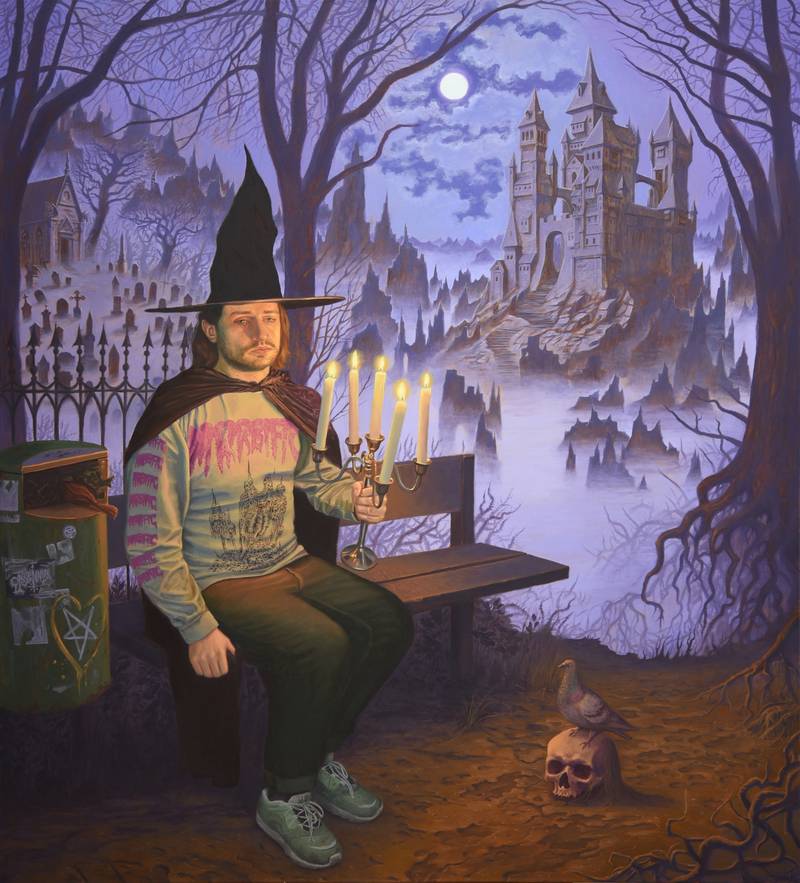

The oldest references apparent in my paintings are from the paintings of 15th-century Florence, where artists depicted more of the bourgeois than the nobles with objects in the portraits that conveyed the person’s interests. I have also included elements which tell the viewer something about the character – in reference to naturalistic milieu portraiture – for example, band shirts. As someone who has worked in the gardening industry, elements of plant symbols have always interested me and are also present in the works.

Joel Slotte, Kuihtunut ruusu ja rauniot, 2024, Oil on canvas, 70x65cm, Photo: Joel Slotte

If I think about the time span from 2015, when you participated in Kuvan Kevät MA exhibition, to this date, the display of reference material in your work has always been quite visible. Is working with background or reference material systematic or random, emerging from social relationships or personal preferences?

Most of it is the latter, but it is also systematic. As background work, I may interview a friend who knows a certain subject well. However, I mainly rely on a certain type of autobiographical tune in how I perceive certain references, for example, in the clothing of the characters.

The works in the 2015 Kuvan Kevät emerged from a classroom photo type, where the characters can be thought of as being related to the classroom and class in an archetype manner. When I made the works, I tried to remember how different characters dressed during my own school term. Nowadays the references are consciously selected, but I have recently focused more on the sub-cultures in which I have spent time myself. The closer I am to the theme I work on, the more truthful the work becomes. This also prevents the characters from becoming stereotypical.

An important opening for me in regards to reference has been literature especially literature with an autobiographical tune, such as Johannes Ekholm’s Rakkaus niinku or Ville Verkkapuro’s Pete. These books are filled with personal history and imagery from popular culture that is close to me. This process intrigues me as a painter – How to bring the lived experience of being in touch with certain popular culture to the works?

The personal conjoins with the cultural (which is always to some extent personal itself). You brought up the idea of autobiography. In some contexts,1 attempts have been made to adapt the concept of autofiction to your works. What do you think about this concept in your own work?

At the moment it does not seem relevant, even though I create a character of myself which is not myself but rather an exaggerated side of a fictionalized self. The process is self-reflective and through it, autofictional material may born, but the method itself is not autofiction per se.

Continuing on this thematic, it is still interesting that you are present in the paintings, as the viewer can find your face in the picture. What is behind this?

It is a conscious decision. For me, making portraits originates from drawing. In 2020, I made an exhibition titled Tonttuyö – Goblin Night at Galleria Live, for which I produced drawings where I portrayed myself as an elf or a goblin. This was during the pandemic and the nearest and easiest-to-get-to model was myself. During that process, I noticed that by making self-portraits I can carve out new features of myself and think about myself as a character.

As well as the presence of yourself, your work could be seen through a certain level of intimacy, collectivity, and nurture which comes from the presence of your close ones in the works. Thinking about the ethical side of personal references, what is the impact and role of people close to you?

Mirroring this to the earlier notions on autofiction, I am reminded of the monstrous examples of the writer Karl Ove Knausgård, using one’s close ones as material, which were present, when I graduated. I have tried to approach the theme by staying in close dialogue with the people I present in my painting. When painting a shared experience I always engage in discussion with the pictured person and the one I have shared the moment with to see if we have experienced it in the same way. Also, the subject pictured in the work gets a provision of the sale if the work is sold.

Looking at early 20th-century portraits painted by male artists of their spouses’ one can see elements of invalidation. I am not interested in working at the expense of the ones close to me. The majority of my friends work in precarious conditions in the cultural field, where every small gesture is important.

Joel Slotte, Nektariineja metrossa, 2023, Oil on canvas, 70x60 cm, Photo: Joel Slotte

Joel Slotte, Omenanpoimija, 2024, Oil on canvas, 60x55 cm, Photo: Joel Slotte

If I broaden the perspective of the last decade to the discussions of the precarious working conditions and infrastructures and their fragility in which we operate in the field of art, how does it seem to you and what is your experience of the field in the last 10 years?

At the beginning of my artistic career, I worked night and shift jobs, living somewhat hand-to-mouth. Nowadays, as I have gotten working grants, the feeling of insecurity still prevails. In general, I would say that feelings of uncertainty and fragmentation. The structures on which this profession is built are extremely fragile and the situation does not get better by the new government cuts to arts and culture – these cuts create an immense lack of vision for the future.

In general, the societal realm doesn’t understand the profession of an artist. For example, the Office of Employment and Economy (TE-office) sees working on an exhibition as work even if one doesn’t get paid. The situation is contradictory: the more one is committed to this profession, the less one can lean on the structures. Many artists work too much at their own expense or don’t get an opportunity to work at all.

In the field of contemporary art in Finland, painting still has quite a strong position, at least compared to some other forms of practicing art and in, let’s say, the Academy of Fine Arts. What are the major discussions in the field from your perspective, compared to the situation 10 years ago?

In the last Kuvan Kevät, to give an example, there was a large amount of interesting and inspiring paintings through which I felt a fresh excitement towards the medium. It seems that a sense of surrealism prevails in painting at the moment – the current situation seems so absurd and incomprehensible that it calls for a visualization of this absurdity. Figurative painting also seems to enhance its role in the field, which is something that differs from the time that I was studying. During my studies, I got comments that figurative painting is, in some sense, embarrassing. Now it seems that the field of painting at least is more permissive.

A thought that I have run into is the virtuosity in your figurative paintings – that the paintings are technically so fantastically executed. Critic Sanna Lipponen has written about the painted surface in your works getting more and more precise and clear.2 When I was looking at your exhibition A Kiss at the Cemetery at Galerie Anhava, which you already referred to, I noticed that I was thinking the same thing: that the trace of the brush is more concise than two years ago in the works at ARS 22 exhibition in Kiasma, for example. A Kiss at the Cemetery presented a range of new works. How did it come to be?

When it comes to being clear and precise, I always strive for as clear a result as possible without being hyperrealistic. A painting is made up of small details so a single element such as a pimple could be thought of as a separate painting itself. The smaller details are pictures within the picture. Another example is the painting Weeping Rain Poncho (festival in Kokkola) and the visual depiction of plastic in it. It was a challenge where I just needed to come up with a solution. Actually, it [the paintings depicting plastic] was the simplest surface to paint in the end.

With the exhibition at Anhava, I started with to work via singular works. Quite early on I wanted a pair of paintings which came to be a diptych of dayside and nightside mirror twins, the works Endless Cape and Howling Candles and Iridescent Wings and the Crackle of Bottle Money, which were separated in the gallery. Next to those I also worked on some larger paintings and still lifes, something that I had not exhibited independently before. For me, exhibitions as such are not any kind of statement but a peek into an ongoing process.

Joel Slotte, Endless Cloak and Howling Candles, 2024, Oil on canvas, 170x150 cm, Photo: Joel Slotte

Joel Slotte, Iridescent Wings and the Crackle of Bottle Money, 2024, Oil on canvas, 170x150 cm, Photo: Joel Slotte

With the exhibition at Anhava, I noticed that I was drawn to the landscapes, especially forest landscapes in the works, something that gives the work a cinematic mode and guides the focus to one’s senses.

I have always liked moving around and spending time in forests. I am aware that the landscape in which I move is often a commercial forest or a tree park, and I have tried to bring this angle to the paintings; the landscape in the work may include paths or other traces indicating that a human has been here. Even if the forest is not completely untouched, it can still provide something important for well-being. Still, at the same time, the works contain a sense of foreignness or bleakness. For example, in the work Wader and Water Striders, where you can see the head of the character in the middle of the water lilies and the thick forest in the background, a complete effect of sensing a certain place is present. I try to keep a hold of this in my work because you can’t touch the forest in a painting but you can sense the landscape.

I used to think that painting should be something that the viewer can step into and that it should be immersive. Now I have learned to trust that this comprehensiveness cannot be expected from painting but it should rather offer small details and surfaces that one can get a hold of and get closer to one’s senses. In 2019, in my exhibition Folklore from the Middens at Huuto Gallery, I showed a painting titled At the Festival of the End of Times in which two characters are smelling – or rather sniffing – Marsh Labrador tea. Depicting smell via the medium of painting is an intriguing task to give an effort. I was glad of the feedback I got: some people felt that the smell was allergenic and disgusting, and for others, the tea-like smell was present in the work.

Just to take a last turn to another sense: the sense of materiality. In your exhibitions, there are sculptural elements such as ceramic works, and these elements can be found depicted in the paintings. What is your relation to these spatial elements?

Through senses of physicality and concreteness, I try to create a weightiness and a spatial possessiveness to how the work feels in the space. I feel like a tourist in sculptural thinking, and I am not well acquainted with the uses of different materials. Still, the feel of the material and three-dimensionality – how the work is in relation to the body – are present in the sculptural works. This has to do concretely with my handprint. As my hands are small, I make small sculptures. The link to painting in this sense is also present: I am not a large person, so my biggest paintings are the length of my reach and my body. And often, of course, much smaller.

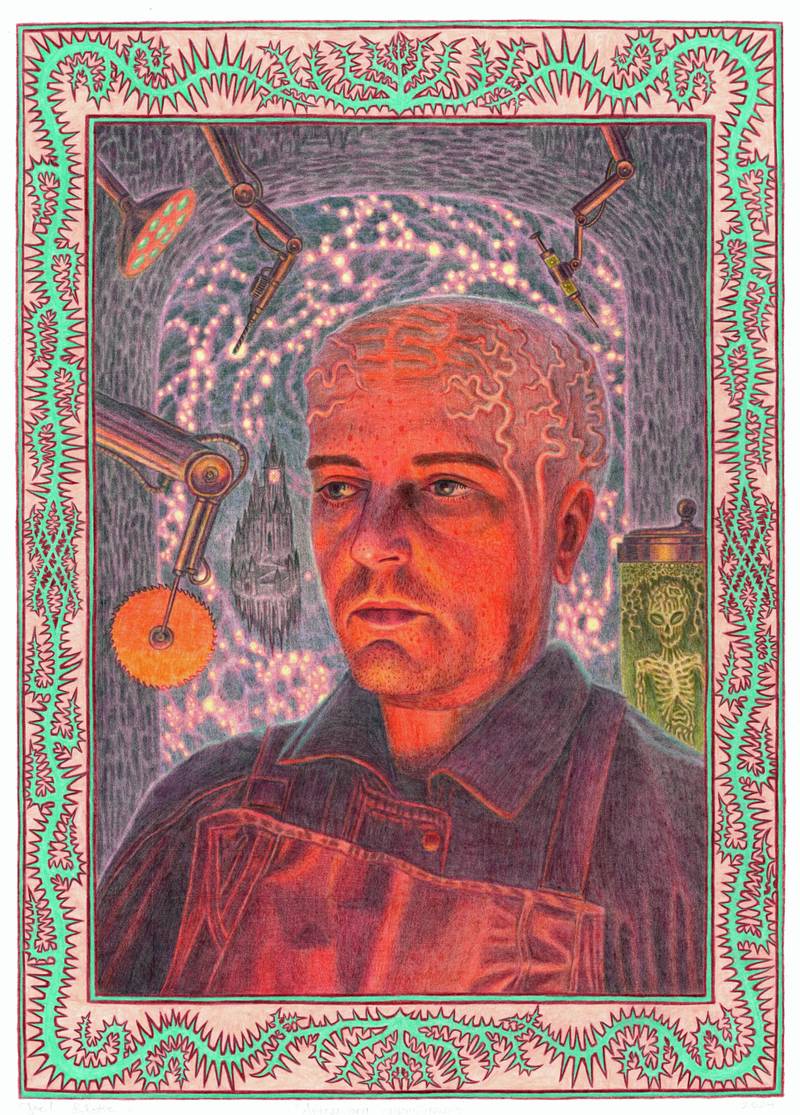

Joel Slotte, Astraalinen ruumiinavaus, 2024, coloured pencil on paper, 51x36cm, Photo: Joel Slotte

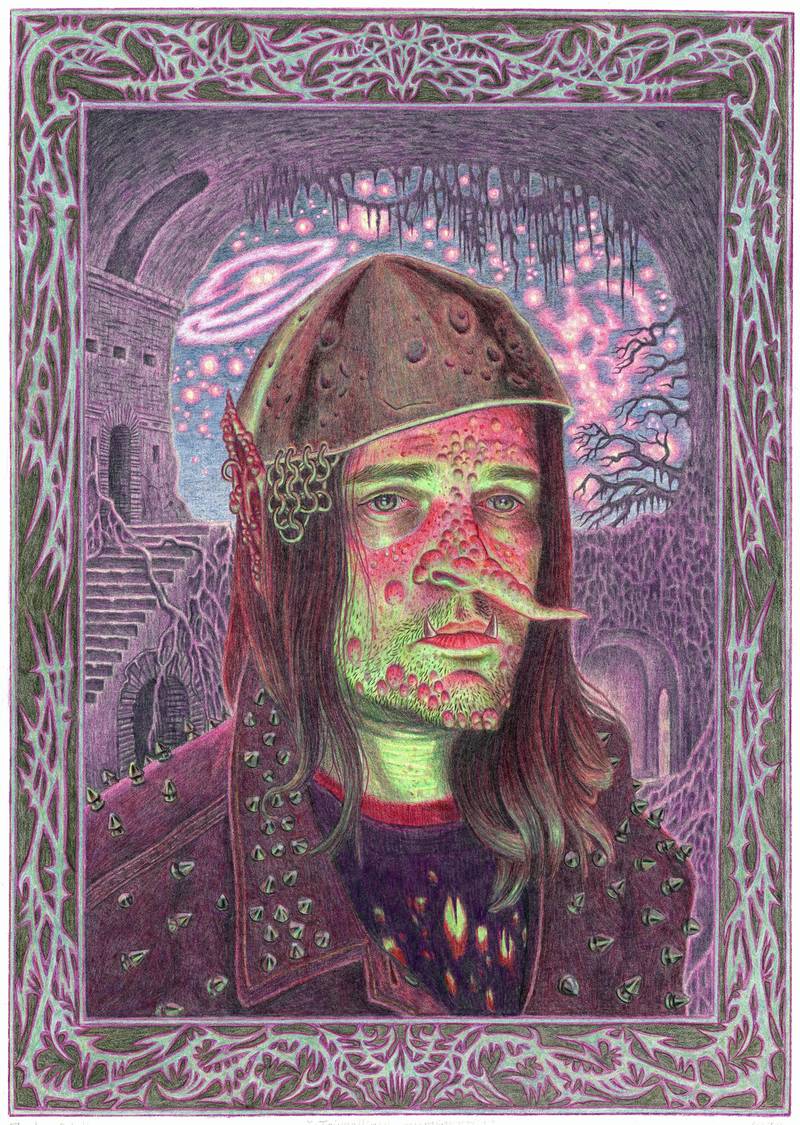

Joel Slotte, Celestial dungeon keeper, 2024, coloured pencil on paper, 51x36cm, Photo: Joel Slotte