Grounding Soils workshop exploring soil as body, land, and commons, Surabaya (Java), July 2024, Image: IIAS documentation team

huiying ng-lou (she/they) is a doctoral researcher at the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society, Ludwig-Maximilian University of Munich. They are a scholar-practitioner and writer working towards critical and empathic rural-urban agricultural learning networks, agroecology, and community-led action research in Southeast Asia.

I often think of the circuitous ways we come to know something and the surprising power with which that knowing emerges. On a visit to a textile-weaving village in northern Thailand, Lamphun province, I came to know a 62-year-old Karen Pwo1 woman. Let’s call her Mae (mother).

‘What do you study?’ the farmer I was visiting asked me in Thai. Mae was sitting with us.

‘Manusayaawithaya’, I say, trying to pronounce the word carefully and stumbling over it.

‘The study of people, she says. Why not [study] agriculture at Maejo [University]?’

I had a ready answer for this since others have asked the same.

‘I’m more interested in people, I say. And agriculture is not just about science (withayaasaat วิทยาศาสตร์) but about mindset (khwaam khit ความคิด).’

Hearing this, Mae perked up and spoke:

“If the rains don’t come, then where will the water be? If the water doesn’t flow, where will the fish go? If the fish don’t come, where will the…” At this point, I was distracted, and when I tuned back in, I realised she was still speaking… “then hed เห็ด (mushrooms) won’t come up.”

What if hed does not come up because it doesn’t want to or lacks the necessary nourishment? Robin Wall Kimmerer (2013) writes of the Anishinaabe word, puhpowee: the force it takes for a mushroom to push up from the earth overnight. Puhpowee rolls off my tongue. It is a transformation as sudden and conditional as the startled awakening of the insects, jīng zhé 惊蛰, in a chinese calendar’s springtime. And just as easily, it can be absent: the mushrooms simply don’t appear.

From Cultivating to Organising

The Peasant Federation of Thailand, founded on November 19, 1974, was one of the most influential movements of that decade in Thailand. It grew out of a simple reason: immense class stratification and agrarian transformation in Chiang Mai Valley, northern Thailand. Membership quickly grew across the northern and upper central provinces, where similar conditions were felt (Glassman 2004). The effects of this stratification are clear today: the very spot where I sat listening to Mae in this valley, is today dotted with monoculture longan orchards. But the effects of that mobilisation remained; with farmers choosing to occupy unused land in 1997 and 2000 (Nattakant 2011).

Agroecology challenges the ways in which agricultural capitalism prevents people from acquiring skills, technologies, and knowledge to cultivate nourishing food. It opposes capitalism’s treatment of food as a commodity.

Nationwide, a rice tax instituted in 1955 was followed by the muzzling of labour unions and an increasing rhetoric of capitalist development from the 1960s. Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat took power in 1958 with US military backing (Glassman 2020). By the 1970s, years of rice taxes had kept agricultural incomes so low that the average wage for agricultural labour was 5-6 baht a day in 1970; by 1976, wages as low as 8 baht a day on larger agribusiness farms were still reported (Turton, 1978, p. 114 cited in Glassman, 2004, 63). Peasants began having to rent land (as tenant farmers), and many left agriculture entirely. Their destination was often the city—so Bangkok has, for decades, enjoyed a surplus of cheap food and labour. This is one kind of agrarian transformation—one that the global South today recognizes well. US support, via its military and intelligence institutions, fostered a Thai military that would learn to use counter-insurgency tactics on students and farmers. However, this fledgling recognition of shared imperial conditions does not reach today’s average urban consumer. In these circumstances, how would the middle-class bourgeois find commonality with farmers enough to coalesce?

As a Singaporean, I focus on agroecological practices among smallholder farmers in Thailand in order to explore how food is grown and sold from the countryside to the city. In one part of my work, I follow—or try to follow—debt trails and chemtrails, tracing the slow evacuation of germplasm’s present and future from soils in Thailand. Soil scientists are beginning to talk about bombed-out soil—the term “bombturbation” coined by US scientists Hupy and Schaetzl (2006) is, to my ears, an awkward description of the destruction left behind. Research by Ukraine’s Institute for Soil Science and Agrochemistry has found that toxicity from chemical residues and reduced diversity of microorganisms leads to a loss of the energy that corn seeds produce as they sprout.2 How often does one think of the energy that propels life?

In another part of my work, I trace historical and ongoing struggles in urban life to establish connections between them, approaching social relations and production through concepts of learning, such as agroecology. Agroecology challenges the ways in which agricultural capitalism prevents people from acquiring skills, technologies, and knowledge to cultivate nourishing food. It opposes capitalism’s treatment of food as a commodity. Peter Rosset and Miguel Altieri (2017), who bring peasants’ politics into scholarship, define agroecology as a set of practices that work against industrial colonization and agricultural capitalism. I am interested in how the very act of processing something—let’s say, coffee being harvested and then sunned—has an emergent quality to it that is both material and vital/alive/living at the same time.3

Agroecology can be thought of as a learning assemblage of the non-human world, cultivator, and eater. Dialogue between two or more processes involves transformation at a systemic and structural scale. Other processes at work between the microbes, water molecules, and chemicals the human body encounters in the soil must be reduced to the physics of contact, the chemistry of ionic and covalent bonds, or the ecology of microbial populations in contact. Machine learning is off to a good headstart; how about studying more-than-human assemblages as they interact? As agroecology entered FAO discourse (Loconto and Fouilleux 2019), its use has spread to more fields that work with FAO language—participatory design, systems thinking, and future thinking. This has been useful. However, I increasingly desire both to name things and celebrate their naming. The former brings clarity, while the latter enriches the world with their presence.

Learning to live, be, feel, and see differently enables substantial change. This is one reason I continue to put effort into building community-led action research with the Living Soil Asia team in Singapore. We ask: How do we follow the work of the extended network and provide support through iterative cycles of research and action? Action that reconnects land bodies with human social relations.

Weaving with the Earth and Plants

Mathana Aphaimool, or Pui as she is known, is the daughter of Phat Aphaimool, a farmer who independently chose to switch from chemical-based corn monoculture to organic agriculture, and who became a well-known leader of his time amongst farmers in the north and beyond. Pui has chosen to plant these heirloom tomatoes this season—and she will save the seeds for the following years’ replanting. These tomatoes are the large and fleshy, irregular-sized ones that now frequent the shelves of organic grocers, small and large.

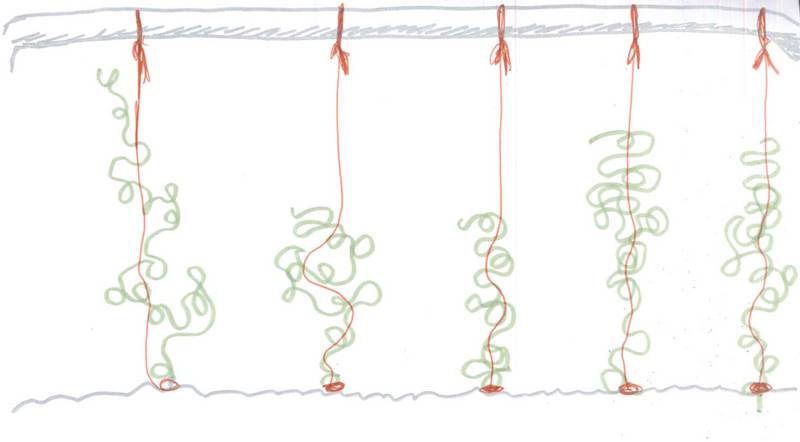

In the waning light of dusk, I creep along the row, twining the yarn around older plants, their dark red fruit spilling out of their basket of leaves. I am twining tomato vines around off-white yarn strings dangling from an aluminium pole. I’m trying to finish three more rows before the sun sets beneath the crowns of the trees cradling Pui’s home and farm. I’m a bit disoriented as I begin—do I tie the tomatoes to the yarn or the yarn to the tomatoes? I’m supposed to wind the yarn through the tomatoes and knot them to the base of the stems so the yarn stays semi-taut—slightly loose but taut enough to act as a scaffold for the curly, wavy green tomato stalks to lean on. But how do I take the measure of tautness till I’m through the tomatoes’ scraggly, curly waves?

February 2022, author’s fieldnotes

It takes a while, but eventually, I get it: by taking the measure of the plant and its body’s slant, the yarn goes just here—along the curve of a crooked spine—and there—beneath a convenient branch—and there again—supporting a leaning stem weighed down by its fruit, pulling it up so it can catch the light.

The yarns are part of a balancing act, and as my fingers grow less clumsy, I reach behind the plant, shifting the yarn around its body. Some plants get a tauter yarn—and some less. My satisfaction with the results differs along the row. The point is not to get them all right but to give them “good enough” support—as with those ideas of scaffolding Vygotsky’s writings inspired. Indeed, the yarns don’t just support the tomatoes; they also show them how and where to grow. As I move along the row, I ponder how old generations need to be unravelled or unwound so that new generations can gain a more solid structure.

The analytic of the learning assemblage, as a concept in geographical literature, focuses on how “learning is produced not simply as a spatial category, output, or resultant formation, but through doing, performance and events” (McFarlane 17, emphasis in original). The place(s) of the learning assemblage is crucial to assembling reciprocal, “sticky” relations to build an ethics of exchange in a “knowledge-intensive agriculture.” These sticky reciprocal relations can also be thought of as ritual: for instance, with this notion of “ritual as a busy intersection” where “distinct social processes intersect” (Rosaldo 1989, 174). In this anthropologist’s view of ritual, ritual is not a “recipe,” “fixed program," or “book of etiquette” (Rosaldo 172) but an “open-ended human process,” an “intersection of multiple co-existing social processes” (172).

In the activities occurring in place, the frustration and calm accommodation with which Pui accommodates her many rituals—watering, maintaining the garden, receiving visitors and bringing them to the agroforest—can only be understood in relation to the force of her conviction. These events are not the kind of events that Rosaldo’s (1989) generation of ethnographers preferred to study: with “definite locations in space with marked centres and outer edges” and temporal “middles and endings” (172). These events are messy, held together by a force of emotion that drives change, and it is this force that catalyses “processes whose unfolding occurs over subsequent months or even years” (173).

Weaving with the earth and the plants with these winding structures, the skills of stitch and weave, knot and loom, spindle and thread may, by happenstance, weave a new kind of light into the architecture of a space and time.

Thinking with the forest

One morning, Pui brings me and the Living Soil team—a small group of friends and co-workers from Singapore—to her family’s agroforest. We are in the foothills of Chiang Mai province. This patch of land, about 18 rai (6-7 acres) in size, was purchased by her father years ago and planted with seeds and plants sourced from the forest. She leads us through the forest, pointing out lianas, shrubs, and herbs. The trees are young and walking paths wide; sunlight sifts through. Pui tells us about the tracks squirrels make as they dig up the galangal bulbs and leave their droppings, which act as fertilizer for the trees. We come to a sapparot grove; the trees have grown large and are shading them, so the sapporot/pineapples receive less light and bear smaller fruit.

This is a place for plant genetics (phan thu kam pheuk พันธุกรรมพืช), Pui says. I plan to sell these as pineapple cultivars. My mother will not be able to return to the forest for the next 5-6 years, as driving a motorcycle may be difficult for her. And because she is busy, perennial plants are more economically feasible. To illustrate her point, as she will do iteratively over the morning, Pui gestures to phak liang, a tree whose young leaves can be harvested. An intern had helped her plant phak liang seeds just last month. She motions to look close to the ground, and I stoop with my video camera, filming, looking, and find a small green sapling with four leaves, just three inches tall. Over this morning, I will find myself chasing to capture each moment of speech-gesture-elaboration, trying and failing to keep up with the fluidity with which Pui lives and thinks with the forest.

“If I don’t learn with my dad, I won’t know the history of this plant, and we will lose this knowledge. Society now is covered with other knowledge, making you feel small and unconfident and think you need to eat some plants and not others. They create changes through the structure.”

The forest—or perhaps Pui’s speech-gesture-elaborations of the forest—is a lot to take in. Phak liang, from just three trees, has grown into saplings sown by animals. To get a closer look at the sapling through the lens of my video camera, I crouch down to look at a little shoot she points out, filming. Close to the ground, the sapling is tiny amidst the leaf litter of old trees, leaves bigger than its own leaves. How strong its ability to shoot up and find its way to sunlight is! I marvel at the size of the plant. As I reencounter the seed-grown sapling through the film I recorded, standing tall at its diminutive height next to the taller pineapple, I recall my sensation in the forest of split time—momentarily pulled into the life of the forest, an arching, layered space with its own temporality, its multiple lives interwoven with Pui’s family’s, and occasional visitors like us.

Pui has already taken several steps, and I am several steps behind, my camera trained on the small sapling. I recount its name, repeating it for the camera. This phak liang sapling was planted from seed three months ago. Phak liang came from three trees visitors had given her, and now their seedlings are sprouting everywhere, planted by animal droppings. They will grow as shrubs for about two meters, are easy to harvest, and are high above the pineapples. They will grow well together, she says.

I want to expand this area as phak liang, Pui says, and grow nang lao in another area as a cover crop. She motions to a large ground shrub plant with spreading dark green leaves, drooping where their weight bears them down. There are three long rows of them, fanning beneath the taller trees. “Do you eat the leaves?” I ask. “No, just the flower. It grows one year, one time; it’s a special menu. My mother comes every week and can harvest all the flowers in a month and sell them at the market. The taste is special, sweet and bitter, mixed, kom kom nit nooy (a little bitter). Usually, it flowers in December and gives ten flowers each season.

Nearby, we spot jak khan, which a member of our group, Na, enthusiastically points out as an edible climbing herb whose stem can be cut and put in soup. Then Pui points out small saplings on the ground amidst shrubs and vines, and before my video camera deciphers the image, I spot a tree whose canopy arches over a bed of tiny green shoots. Maak faay. You can eat the fruit, Pui says. What looked like grass turned out to be saplings; they were shooting up all around the roots of the tree. Na crouches where the blanket of saplings ends and gushes, “Can I take one of these home to plant?” Pui approves, and Na produces a small plastic bag and gathers soil and a sapling. We hover around looking at it, and as I hold my camera close, the others dip their hands into the soil, smelling.

Pui needs to learn the uses of all these plants. As we reach a cluster of low-lying plants with wide, broad leaves fanning out from thin stems, she introduces them. “If I don’t learn with my dad, I won’t know the history of this plant, and we will lose this knowledge. Society now is covered with other knowledge, making you feel small and unconfident and think you need to eat some plants and not others. They create changes through the structure.”

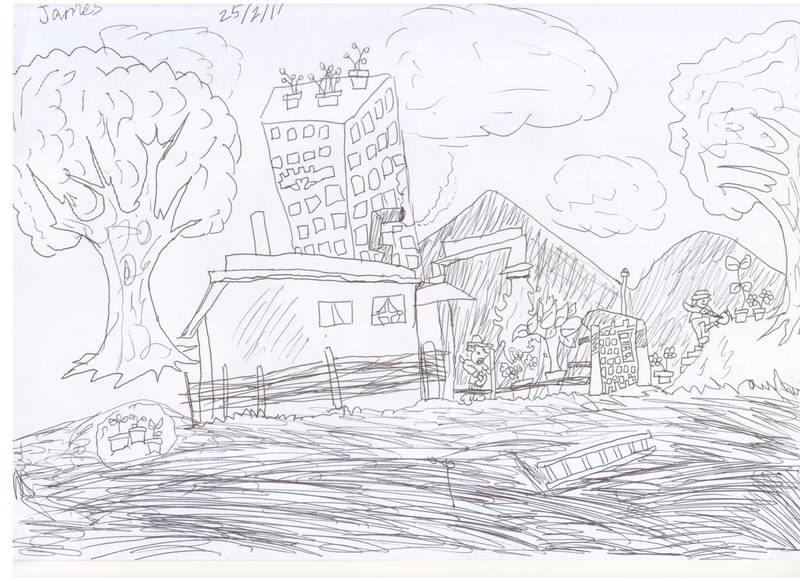

Participants’ sketches of urban nature, 2017.

When narratives about agriculture overlook sound and story, they lose agriculturalists’ referential worlds, where mimesis and play, the material and the semiotic, are central. In my work on urban natures in Singapore, I have tried to understand the limits of Singaporean understanding of where food comes from. I have always aimed to shift local understanding beyond the limiting frame of reference. As this work has grown (and I have changed), speaking with the same optimism and confidence about this possibility has become harder. But regional solidarity remains the aim. And I learn equally, from groups in Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Myanmar. One keeps going despite typhoons, floods, and governments that focus on their own politics. Learning from Pui, who embodies a deep connection to the land, valuing intergenerational knowledge and sustainable practices, makes us view agriculture as a complex system that respects nature and its resources. Mae’s story—which took me around the forest—gives listeners a way to place the relational, sensory world, which science calls an ecosystem. So, one can place the energy that pushes life’s currents in memory and imagination.4

The cover image is courtesy of the IIAS documentation team. A short description of the ‘Grounding Soils’ workshop is available on the online IIAS newsletter: Workshops and Film Screenings at ICAS 13. Available at: https://www.iias.asia/the-newsletter/article/workshops-and-film-screenings-icas-13