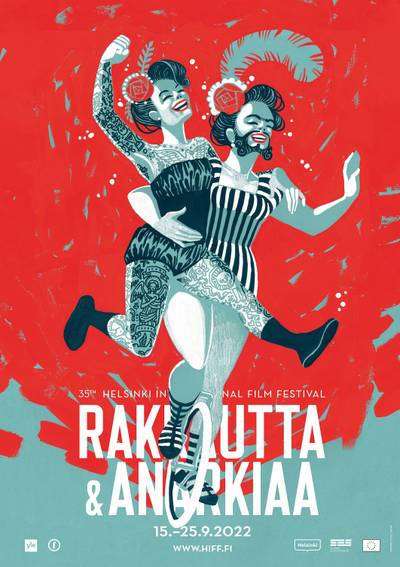

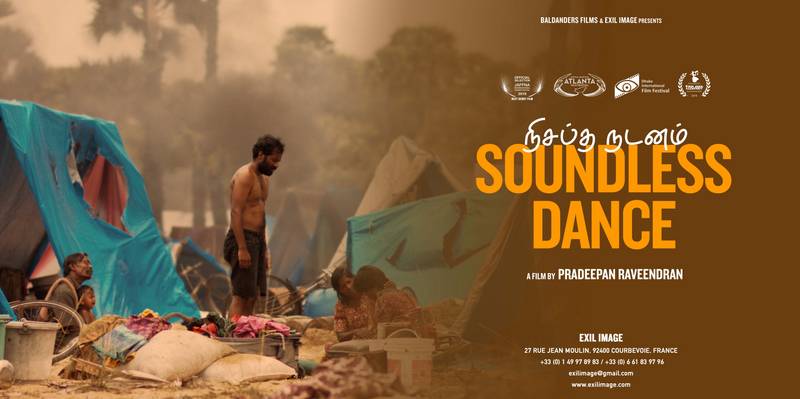

Soundless Dance, directed by Pradeepan Raveendran

சிந்துஜன் வரதராஜா (Sinthujan Varatharajah) is an independent researcher and essayist based in Berlin. The focus of their work is statelessness, mobility and geographies of power with a special focus on infrastructure, logistics and architecture. Their first book “an alle orte, die hinter uns liegen” (“to all the places we have left behind”) was published in September 2022 in Germany by Hanser Verlag.

Soundless Dance | Directed by Pradeepan Raveendran | Duration: 1h 29min | Language: English, Sinhalese, French, German, Tamil | Streaming on CINELOGUE.

In his remarkable 2019 debut feature film Soundless Dance, Raveendran narrates the horror of the Vanni genocide (2008-2009) through two physically and politically vastly different places. Thousands of kilometers apart, both lands are bridged by a young refugee who sleepwalks through them, neatly weaving them into a single landscape that is inhabited by a torn, oppressed and uprooted people who are seeking stability, safety and a future across these grounds. The director, a refugee himself, opted to optically differentiate both of these spaces through aspects of climate, landscape, flora and clothes, but sternly not through matters of language and emotions. Feelings are what tie together what appears as two separates at first glance into one.

The film begins with Siva, who is seen on his way to an appointment at a French visa office, where his political asylum claim is under review. To his surprise, his French case officer nonchalantly rejects the documents he had carefully assembled and brought with him. He dismisses them as mere family documents, i.e. documents without “real” meaning. Siva is asked to provide written proof by the “Sri Lankan” state instead that supports his claim to a personal threat to life that would justify his asylum case in France. The refugee, visibly irritated by this demand, asks his Tamil translator in an astonished voice how it was possible to retrieve such a state-issued document to begin with, let alone at this very moment. The protagonist’s temporal annotation - the now - is a reference to the timeframe of Pradeepan Raveendran’s film Soundless Dance. Set sometime in January 2009, we observe Siva, played by Patrick Balaraj Yogarajan, in his struggle to find security and peace in his new European exile in the midst of a live genocide in his physically distant homeland.

Siva in the lawyer’s office at the French Visa Application Centre

Young Siva and his friend Rhagavan by the aquarium

From Paris, we suddenly move onto a rural road squeezed between palmyrah trees and bamboo fences. A tractor approaches, carrying a dozen men in militant camouflage and guns in its loading area. The sound of the vehicle fades as the voices of children emerge. In a front yard adjacent to said road, we see three Tamil children play with water guns. Young Siva and his friend Rhagavan pause to head to a small aquarium kept in a hut in that same yard. There, they curiously watch and comment on the fishes trapped inside. Realising that one of them was pregnant, they innocently begin to wonder how fishes may give birth, before deciding to just feed them. A loud humming interrupts this warm scene. In the next scene, Rhagavan has run off and is heard from a distance warning his friend of the arrival of an aerial bomber. With a loud detonation, the yard the Tamil children had played in moments before, submerges in dust. When the dust slowly settles, we see wounded Siva helplessly lying on the ground.

In Soundless Dance, Raveendran collapses time and space through recurring motifs of dreams, memories and imaginations. These motifs help powerfully subvert the very common assumption that being physically removed from violence can be equated to escaping its very reach.

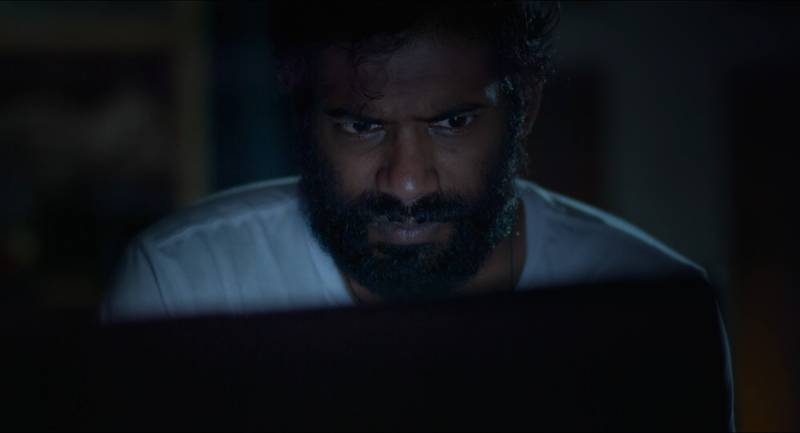

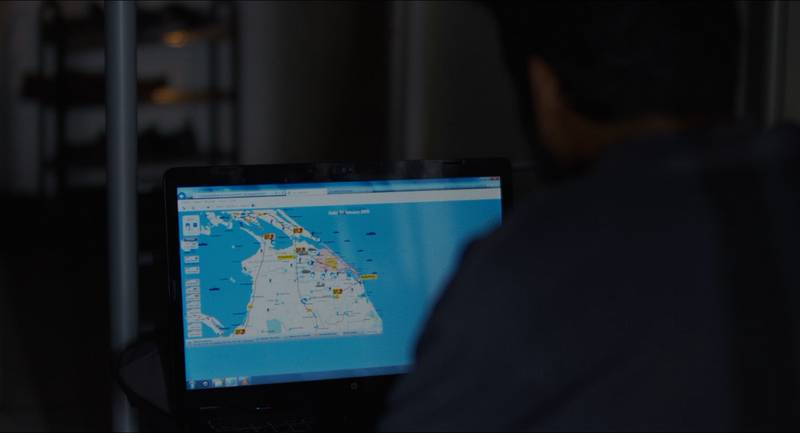

Back in the present, Siva walks into a northern European forest, pausing at a lake to reflect. He later returns home, where he switches on a desk computer and types into a web browser the domain of the “Sri Lankan” Defence Ministry. Siva clicks on a virtual map showing the Vanni with little thumbnails of soldiers, tanks, artillery trucks and navy ships plastered on top of it, indicating the advance of the same army whose website he was consulting. The young man hovers with the cursor for some seconds over the western edge of the region, moving eastwards towards Kilinochchi, the capital city of the de-facto state of Tamil Eelam, and the city Siva once called home. According to the map, Kilinochchi had already been captured by the “Sri Lankan” Army and declared a “liberated area”. Siva zooms further into the eastern corner of the region, which had been marked in red and parts of it declared a “No-Fire-Zone”, an arbitrarily demarcated area by the “Sri Lankan” state where displaced Tamil civilians were told to find protection from state bombings. This red zone was small and alarmingly cornered by several blinking arrows that pointed from all directions towards this tiny edge of land, which, at its easternmost, disappears in water. Siva is seen carefully studying the military map before switching to another website, an Eelam Tamil news website, where he clicks on the thumbnail of a video. A scene in the midst of a jungle appears. Recorded with shaky hands, the lens moves as hastily as the eye of its recorder. Tamil civilians are seen taking shelter from constant and advanced state shelling in and between tents, metal sheet buildings, mud bunkers and vehicles. Screams of death and the injured blast through the device’s speakers. From a sterile map, the Vanni had transformed into a living nightmare in front of Siva’s eyes. It was here, right in Siva’s room, and in front of our eyes.

Siva starring at screen

Computer screen map

In Soundless Dance, Raveendran collapses time and space through recurring motifs of dreams, memories and imaginations. These motifs help powerfully subvert the very common assumption that being physically removed from violence can be equated to escaping its very reach. While Paris seems far enough to be spared from the bombings of the “Sri Lankan” state, it isn’t for the effects of these bombs to still affect related people. By observing a genocide from outside its centre of violence, Raveendran manages to show how, when life can fall apart for some in the face of genocide elsewhere, the every day under racial capitalism forces the affected to continue to function almost unruptured and unmoved by that same violence. This isolation and tension accompanies the film up until its very end. It first appears in the opening scene in the visa office, where Siva’s asylum case officer seems entirely ignorant of the devastation unfolding in parallel in his homeland. And it continues at his workplace, where he is expected to leave his sorrows outside of his working hours. During his long commutes to and from work, his worries and frustrations are then met with complete indifference by his human environment.

When an early morning call abruptly wakes him, Siva unexpectedly finds himself connected to Vanni again. On the other end of the line is his mother. She tells him of the destruction of their house and their repeated displacement thereafter. The “No Fire Zone”, as the arrows in the military map from before had indicated, didn’t live up to its promise or name, his mother continues. The bombs were arriving from all directions into this small patch of land, she narrates. Amidst the horror he was processing, this however wasn’t the information that devastated him most. It was the news of the disappearance of his older sister Pushpa, who his mother reports to have been lost amidst the chaos of mass displacement and, worse, the abduction of his younger sister Kala by the resistance to fight on the front lines. Kala’s fate begins to shake him. It quickly translates into recurring nightmares for Siva, in which he is seen frantically searching for his younger sister across the carnage in besieged Vanni. The focus of his hurt points not only to his close relationship to his younger sister, but also to his seemingly troubled ties with the Tamil armed resistance. This is confirmed in another memory, in which Siva is seen in a heated argument with his childhood friend Rhagavan, who reappears as a grown man following the yard bombing scene. As grown ups they deliberate the merits of armed versus non-armed resistance. Rhagavan, who, unlike Siva, had in the meanwhile joined the movement, tries to convince him that only by holding onto their arms will the state ever engage in serious negotiations with them; that what Siva considers peace is no real peace for his people. A ceasefire isn’t the same as actual freedom, Rhagavan tries to convince him. Siva combatively claims that it is everyday people who are forced to pay the price for armed resistance. His friend sharply cuts him off. If Siva is convinced that the armed struggle is useless, he too can leave and let them fight, he states in a raised voice.

Siva at home, having a panic attack

Later, Siva is actually seen departing Killinoichchi at the behest of his parents. Though visibly reluctant, they were hoping for him to be able to better financially support his family, particularly when the peace talks between the state and the resistance were to end. It indicates that Siva must have left the island sometime after November 2005, when the Sinhalese chauvinist Mahinda Rajapakse first came to power, and an end to the Norwegian-brokered peace talks between the colonial state and the independence movement became imminent.

While these socio-economic realities allow for Siva to be employed in this restaurant without requiring higher French language proficiency, and while being able to communicate in his mother tongue there, the director hereby also sheds light on another reality: the omnipresence of his people in the inner city, who are, even when kept in invisibility, very present in its central workings.

This was also a time when many Eelam Tamil asylum seekers were arriving in France, something Siva’s lawyer anecdotally states at the beginning of the film. In France, Siva ends up taking a job in a French restaurant in central Paris, working in a cramped backdoor, maybe even a basement kitchen. Raveendran hereby references a common employment dilemma for refugees rooted in a political and economic conundrum, in which a lack of French language skills, a notorious dismissal of foreign educational achievements and severe insecurities surrounding their residency status in France creates a bottleneck for many of them. It forces refugees, particularly young men, to join a shadow workforce in France’s capital’s restaurant industry. This is especially true for Eelam Tamil refugees. Today, Paris’ restaurant industry, almost irrespective of cuisine, is to some degree dependent on Eelam Tamil workers. Some claim the gastronomy sector would even crumble wasn’t it for these exploited refugee workers from this faraway conflict that seemingly produces an endless stream of low-wage labourers. Siva’s workplace, for instance, serves what appears to be French food. Still, almost all of the kitchen workers, including the head chef, are poignantly Eelam Tamil, who most likely never experienced formal training in French cuisine. Like the protagonist and his colleagues, most Eelam Tamil workers are confined to back kitchens, where customers of upscale restaurants never get a sight of them, let alone associate them with the food they consume. While these socio-economic realities allow for Siva to be employed in this restaurant without requiring higher French language proficiency, and while being able to communicate in his mother tongue there, the director hereby also sheds light on another reality: the omnipresence of his people in the inner city, who are, even when kept in invisibility, very present in its central workings. This was recently highlighted when French national baking prizes were awarded to Eelam Tamil bakers in Paris, bringing their disproportionate presence in the local food industry and in their hands in the maintenance and excellence of French national culture to the fore, allowing for these workers to be shifted from constructed racial and class invisibility to temporary national fame. But for how long?

Siva at work at a French restaurant in central Paris

And while most of these blue-collar workers help improve the quality of life for the inner city wealthy, they can’t afford that same increasingly expensive city. Like other racialised working class people, Eelam Tamils are often forced to live outside the circular highway in satellite bedtowns, notorious for bad housing, inferior public transport, job scarcity, poverty and police brutality. From there, they are compelled to take tedious early morning and late night commutes on buses, suburban trains and then metros to their inner city workplaces, where they meet a largely white bourgeois inner city that depends on them, yet mostly pretends they don’t exist and don’t matter. At the end of their shift, they repeat their long arduous journeys to their outer city world, to leave that very city they serve before being forced to continue this cycle the following day. Likeso, Siva is often seen in the film commuting, showcasing how much valuable lifetime he and people like him are forced to waste in transit; how, through the spatial manifestations of socioeconomic inequalities, the convenience of few is by design; manufactured and dependent on the inconveniencing and vertical demobilisation of the many.

Siva in his daily commute from home and work and back

Following one of these shifts, Siva is revealed sleeping in a bunk bed in a crowded flat where he lives with other Eelam Tamil men, all refugees and all unrelated to one another. They share a cramped space that leaves little room for privacy and intimacy. To escape such suffocating environments and the social difficulties they may produce, many banlieu residents seek relief outside, be it in public spaces, parks, streets or malls. Many also venture to some of the inner city’s boroughs, particularly those adjacent to said banlieues and accessible through RER trains (suburban trains), areas that are then considered “sketchy” because of their presence by inner city residents. In one scene, Siva is seen venturing into La Chapelle, the Eelam Tamil neighbourhood in Paris. The area adjacent to Paris Gare du Nord station in the 10e arrondissement, frequented by the RER B train that connects the city to its northern suburbs on the way to CDG airport, formed an important gateway for Eelam Tamil refugees in the 1980s and 1990s. There, they found warm shelters and a receptive care infrastructure. Today, however, despite the area being popularly known as Little Jaffna, very few Eelam Tamils live in the grand Haussmanian buildings rising from and around Rue du Faubourg Saint-Denis’ skies. La Chapelle is primarily a commercial area in which Eelam Tamil presence is concentrated and displayed on the street level, but largely absent from the higher floors due to the inner city’s steep rental market. Nonetheless, it forms the heart of Eelam presence in the city and country even, where a semblance of community and spatial normalcy can be mimicked and felt; where Eelam isn’t just a memory but a physical manifestation.

La Chapelle, the Eelam Tamil neighbourhood

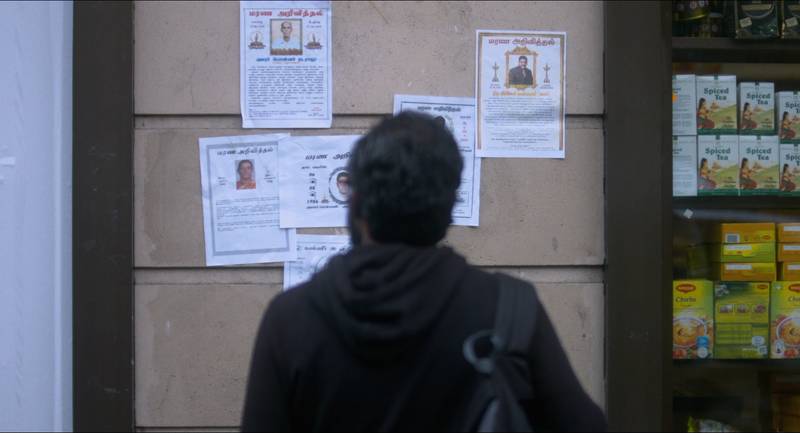

Besides people and food, Tamil presence can easily be identified in the area through the ubiquitousness of Tamil letters, religious signs, shop names that are often direct references to lost geographies as well as political imagery and symbols of the independence movement. When carefully observing the walls between shop fronts, you will also quickly come to note obituaries put up for people who have died either at home or in exile. It is a way of conveying information on death that takes inspiration from Eelam and has also become widespread in exile. While connecting new geographies to old ones, this needs to also be seen as a response to the condition of forced mass displacement, in which the severing of personal ties through mass dispersion is counteracted by techniques that serve to inform, remind and reinforce ideas around community and social cohesion. On the way to meet his friend, Siva passes one of these walls and halts. He studies several obituaries hung for a number of people, some attached with coloured, some with black and white photographs.

Considering that most genocides often do not achieve the goal of completely wiping out a population, the realpolitikal intention of many is to destroy as many as possible while deterring the remaining from staying. Additionally, genocidaires often ensure that the surviving population becomes unable to continue life as it was before.

By the date and place of origin legible on these handouts, it becomes evident all of the people had been killed only days before in Vanni by the “Sri Lankan” Army. As was common during this carnage, most of those killed were, if they were lucky, hastily buried without actual rituals and/or left in unmarked graves there. For those for whom cremation was their way of sending off the soul of the dead, it was a stark departure from their own traditions and a painful reminder that the state even denies their selfhood in death. And while their bodies were left to rot, while the state denied their killings, they were still remembered somewhere far away from the soil they were killed for and the state that denied their existence. The scene is a moving reminder that though the bombs were absent in Paris’ Eelam Tamil area, death wasn’t. Paris wasn’t Vanni, but Vanni was present right here, in Paris, too, through Eelam’s displaced people.

Siva looking at the obituaries posted on street walls at La Chapelle

When Siva is later seen having a cup of tea with his friend in a nearby Tamil restaurant, he begins to enquire about his family’s well being. From the dialogue it becomes clear that his friend’s family was also trapped within the war zone. Unlike Siva though, he hadn’t heard from them for months. The International Red Cross, the only humanitarian organisation left in the area after the state had evicted all foreign aid organisations from Tamil Eelam, was not able to provide him any viable information about their whereabouts. The conversation sheds light on the severe difficulties displaced Tamil families experienced throughout these long months in their search for their relatives, and how this anguish pushed many into despair. This anguish forms an aspect of genocide that’s often underdiscussed in the portrayal of such violence, something the film clearly attempts to counter by narrating a genocide from a significant physical distance. While violence is commonly reduced in analysis to its immediate impact area, the actual toll of such violence often reaches far beyond the obvious crime scenes. This is especially true in the case of mass atrocities and resulting mass displacement, where the psycho-social repercussions of such crimes are incredibly wide reaching. Considering that most genocides often do not achieve the goal of completely wiping out a population, the realpolitikal intention of many is to destroy as many as possible while deterring the remaining from staying. Additionally, genocidaires often ensure that the surviving population becomes unable to continue life as it was before. They actively and intentionally produce a people that are slowly disintegrating from the inside. Thus, it becomes paramount to consider genocides in their actual scopes, i.e. to consider them in their real depths, directions and lengths. Just as a ceasefire can’t be equated to actual peace, a genocide doesn’t just an end with the silencing of weapons.

In the film, the protagonist dictates our point of view, forcing us to confront questions of proximity, safety and affect from this particular angle, helping us to understand that to live a genocide is a distinct hell, but to watch the genocide of your own people from afar isn’t an entirely different hell, but a segment of that same hell designed by perpetrators. In the case of the 2008-2009 Vanni genocide, displaced Eelam Tamils weren’t just forced to watch the annihilation of their homes and people from afar, but also the wiping out of all physical traces of their dream of political independence. Unable to meaningfully change this course of actions despite prolonged global protests, occupations, hunger strikes and even the self-immolation of several, a crisis started to set in amongst many. Raveendran chose to introduce the film with real footage from such protests in Paris. In one moving scene we can see a Tamil uncle being manhandled by French police officers, desperately asking them in their language to respect them, people protesting for the survival of their families. It showcases the frustration many Eelam Tamils, internally or externally displaced, felt at the time in face of the complete idleness of the world towards the crimes against their people.

Raveendran consciously chose to tie original footage from Vanni sent by Tamil journalists and resistance networks into his film, blurring the fine line that separates fiction from reality. By doing so, he confronts non-Eelam Tamil viewers with visual evidence of a crime many will most likely never have seen or heard of before.

Symptoms of depression, sleeplessness, and eating disorders, all indicating a collective mental health crisis, were common at the time. Self-harm, including suicide, was also a daily affair, reminding us that no statistic will ever mirror the real scope and depth of such violence on a people. The killings continued, even far outside of the “Sri Lankan” state’s claimed borders. In a later scene we see Siva visit a Tamil house in a Parisian suburb where a large number of people had gathered. What looked like an ordinary gathering turns out to be a death house for Siva’s friend’s father. He had found out that his father had been killed by the Sri Lankan Army days before. Here, Raveendran provides a glimpse into the difficulty of mourning at a distance and the absence of a body. Besides that the information of the dead arrived days later, delaying the act of mourning; rituals couldn’t be performed without his presence. And yet people had gathered in a helpless attempt to mimic how they would mourn weren’t they displaced across different parts of a world; weren’t they suffering from genocide. While death had become a looming present, it similarly became an abstraction, detrimentally informing ways of remembering. Anguished by his friend’s resignation to the news of his father’s killing, Siva begins to question the reliability of the information. To his surprise, his friend remains unmoved by Siva’s scepticism, rebutting that the only surviving eyewitness to his father’s death, his cousin, was able to escape the caged territory before being able to reach him to pass on this vital piece of information. If he can’t trust his own relative, his friend continues, who else would he be able to trust? With communication infrastructure severely hampered from targeted attacks against hospitals, medical staff and humanitarian aid workers, with media institutions, telephone and internet lines repeatedly cut off, and journalists systematically murdered, information about life and death became increasingly more difficult to obtain from within the remaining non-government occupied territories.

Siva with his friend

Footage from Eelam Tamil protests in Paris

The obituaries Siva had seen in La Chapelle, in addition to the news of his friend’s father’s killing, pushed him to finally face the likelihood of his family suffering a similar fate. In a desperate attempt to find evidence for his family’s survival, he returns home to search through more recent videos sent from Vanni. This became a common and daily practice for many situated outside of the besieged area, fearing for their relatives’ safety. Forced to rummage through endless videos and photos arriving every day from within the besieged area depicting mass killing and suffering, the images of the time slowly burnt themselves into their memories. At some point in the genocide, this became the only viable way of attesting to their kith and kin’s final living and dying moments. Unlike the rest of the world, they couldn’t afford looking away. Here again, Raveendran consciously chose to tie original footage from Vanni sent by Tamil journalists and resistance networks into his film, blurring the fine line that separates fiction from reality. By doing so, he confronts non-Eelam Tamil viewers with visual evidence of a crime many will most likely never have seen or heard of before. A crime much of the world remained idle and ignorant towards when it occurred, when it was still possible to stop it. Back in front of his computer, Siva pauses at the sight of a young woman dressed in a red nightgown, lying injured in what looked like a makeshift hospital. He zooms into the picture, towards the face, before whispering Kala, the name of his younger sister. But was it really Kala or Siva’s despair recognising his sister where and when she was no more?

Still screen from video footage showing Siva’s sister, Kala

Soundless Dance feels like a sleepless nightmare, in which Paris-based director Pradeepan Raveendran manages to captivate many of the gruelling emotions exilées experienced during these seemingly endless weeks between September 2009 and May 2009. It is a convincing and intimate portrayal of the violence of genocide through the eyes of a young refugee and his surroundings, who sees his life fall apart when he was told it was just about to improve. By choosing to center Siva, a single individual, in what is an entire people’s tragedy, Raveendran allows us to observe at a micro-level, through the protagonist’s inner and exterior world, the depth of individual and social ruptures caused by such violence; that even when traces of physical injuries have disappeared, their afterlife can continue to take shape somewhere between and in you. In this film, the director, an Eelam Tamil refugee himself, sensibly approaches the question of how genocide in one place impacts its people in another place. Observing Siva, we see that physical distance is but a variable that reflects on and speaks little to emotional distance; that even when uprooted oceans apart, organic ties between people remain – particularly in the face of settler-colonialism and a people’s genocide.

When viewed within the present, much of the film will possibly remind non-Eelam Tamil viewers of Palestinian refugees abroad experience and struggles against Israel’s genocide of their people in Gaza. And while the similarities are self-explanatory and by political design, significantly more attention has been given today to the Gaza genocide than the Vanni genocide.

Considering that at the time of production of the film, less than ten years had passed since this “Sri Lankan” genocide had wiped more than 170,000 Eelam Tamils from the surface of this earth within a short span of nine months – 6% of the overall Eelam Tamil population and a quarter of the population of the Vanni –, and considering that no feature film had yet portrayed this part of our recent history, this film arguably also functions as an advocacy tool against the forgetting of the fate of Raveendran’s people and the recognition of their plight and struggles. Using the means of film, Raveendran introduces the subject to an audience most likely unaware of what is already considered historic to some, but remains a living and breathing nightmare for others. He responds to the need to tackle the lack of political and legal recognition and accountability for these crimes by using the realm of cultural production to establish and normalise Eelam Tamil experiences, testimonies and perspectives where they are rendered absent.

Soundless Dance by Pradeepan Raveendran is as much fiction as it is non-fiction. Its relevance is also not limited by time. It is historic as it is current, the past and the present. When viewed within the present, much of the film will possibly remind non-Eelam Tamil viewers of Palestinian refugees abroad experience and struggles against Israel’s genocide of their people in Gaza. And while the similarities are self-explanatory and by political design, significantly more attention has been given today to the Gaza genocide than the Vanni genocide. This discrepancy is often argued by way of images, claiming that the images existing in Gaza rendered this genocide difficult to ignore for the world. It assumes that Vanni didn’t didn’t produce any or enough images at the time. In a twisted way, such rhetoric helps shift responsibility away from viewers towards violated people, who are indirectly told not to have forced themselves enough into someone else’s eyes and consciousness. This argument peaks in questionable claims that, for instance, the Gaza genocide is the first live broadcasted and documented genocide in the world. Raveendran’s film, however, quietly reminds us that the Vanni genocide, like many other genocides of this European century, didn’t happen off-screen. Quite the opposite. Siva searches for images and videos from the carnage, be it on the TV, his computer or his phone. And if he was able to access them, then so were others. The difference wasn’t the absence of the image but how different images from different places, people and histories evoke very different reactions in outsiders. Soundless Dance remains the response of the world to the many souls that turned into ghosts in Vanni.