A bulldozer destroys the Israeli heavily militarised Israeli wall besieging Gaza during “Operation Al-Aqsa Flood,” on October 7, 2023.

Omer Mohamed Gorashi is a Sudanese American designer and photographer. His work interrogates contested landscapes, uncovering marginalised histories while addressing themes of power, memory, and disparity. He holds a Master of Architecture from Columbia University GSAPP and a pre-professional degree from the University of Virginia.

Ruins are not just naturally forming relics of the past—they are calculated, (de/re)constructed, and weaponised with intent. Some are left as reminders, others are wiped clean, their absence as deliberately planned as their destruction. In this conversation with The Funambulist’s editor Léopold Lambert and head of communications Shivangi Mariam Raj, we discuss Bulldozer Politics—how demolition and displacement are framed and justified through the rhetoric of modernisation, law and order, and national progress. While their contributions to this issue (#56 November-December 2024) focus respectively on Palestine and India, the experiences extend to broader struggles where architecture, law, and violence intersect in state-led erasure and resistance. Bulldozers, often seen as neutral tools of industrial demolition, are instruments of territorial domination, urban redevelopment, and political suppression. Yet within these acts of destruction, counter-narratives emerge—poetry, mourning, and collective remembrance—that reclaim agency in the face of state-sanctioned ruination. If ruination is a strategy of power, it is also a site of resistance.

With recent developments in Syria, Palestine, and Sudan, the reality of ruin—both as a physical condition and a political strategy—demands a renewed lens. Reading this conversation in the wake of these crises, we invite you to look at ruins differently: not just as remnants of loss, but as sites of memory, survival, and refusal.

OMER: How can the framework of Bulldozer Politics be applied to analyse contemporary redevelopment projects in contexts beyond those commonly discussed, such as Palestine, India, Egypt, or South America? Specifically, how are destruction and displacement justified under narratives of modernisation, progress, or law and order in these other scenarios?

LÉOPOLD: The Funambulist does its best to respect the uniqueness and specificities of each situation while recognising the commonalities that many of them share with each other. In the case of the Bulldozer Politics issue, the aim is to present an analytical method that applies particularly to Palestine and India but could also be relevant to other contexts. This method suggests that when we encounter ruins and debris, especially those caused by bulldozers, we should not be fooled by the chaotic spectacle they embody. Behind this destruction is a precise strategic political order designed to subdue certain communities. This insight is something many readers can apply to their own contexts or ones they are familiar with.

SHIVANGI MARIAM: What stands out in the popularly imagined figure of the bulldozer is its use as construction equipment, something that aids in building things rather than destroying them. However, this issue highlights the use of bulldozers as a weapon. When we examine the spatial contexts of Tamil Eelam or Indian-Occupied Kashmir, where methods such as chemical warfare, arson, and aerial bombing have been used against the colonised peoples, bulldozers become an extension of these destructive technologies, stripped away from the innocence often associated with them.

Take JCB, a British construction equipment manufacturer whose products are deployed for spatial violence not only in Palestine and Syria but also in India and Kashmir. It’s difficult for many to believe that JCB could be linked to such destruction, especially considering they sponsor a literary prize in India, claiming to support writers’ voices. This issue challenges the view of bulldozers as mere construction tools and aligns with *The Funambulist’*s broader editorial line that architecture, as a discipline, is complicit in the political domination we observe around us.

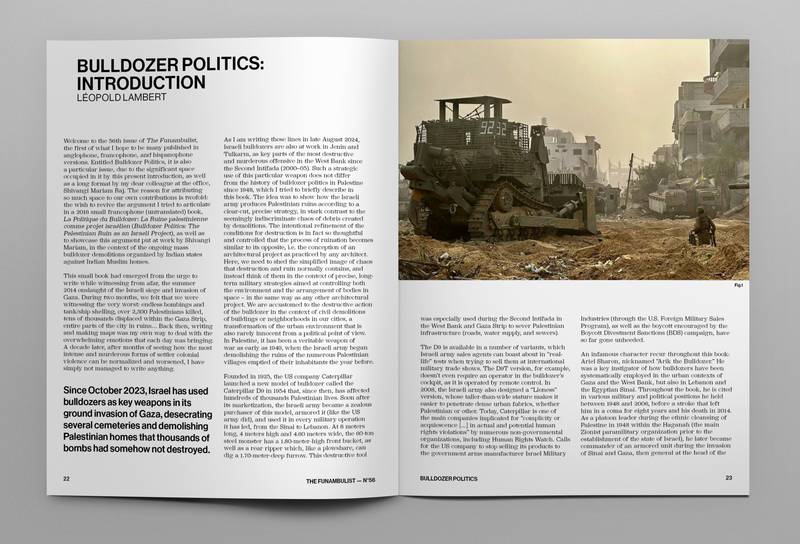

Introduction to The Funambulist 56 Bulldozer Politics by Léopold Lambert.

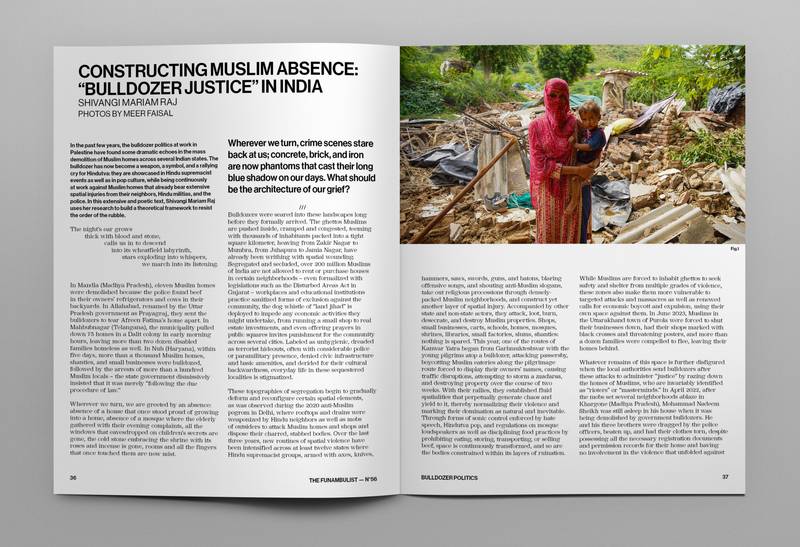

Contribution to The Funambulist 56 Bulldozer Politics by Shivangi Mariam Raj.

Léopold, you describe bulldozer demolitions as strategic and intentional, akin to architectural construction. How has the Israeli military’s use of bulldozers evolved since 1948 or during Ariel Sharon’s era? Was this shaped by changes in Palestinian resistance tactics or international pressure, though the latter seems minimal?

L: In my editorial introduction to this issue, which is mostly taken from a short book I authored titled Bulldozer Politics (La politique du bulldozer in French) back in 2016, I articulate an argument around ruination—the act of transforming something into a ruin, specifically in the context of Palestine, which is particularly extreme. The complicity of a US company like Caterpillar has been well-documented for years. The Israeli army has even customised their D9 bulldozer, weaponising and armouring it to operate autonomously in Palestinian neighbourhoods that are targeted for destruction.

What has changed since 1948 is the level of technology applied to the bulldozer. However, the methodology remains the same: the destruction of Palestinian homes is central to the Zionist project of denying and dispossessing Palestinians from the land claimed by Zionists. Even in the early years, during the 1950s after the Nakba, bulldozers were used not only to destroy Palestinian villages but also the ruins of those villages. This is significant because it’s not just the homes that are demolished; the ruins, which could have told the story of their past existence and the destruction they faced during the 1948 Nakba and the ethnic cleansing, were also erased.

The same bulldozers were used in 1967 to demolish the Maghrebi neighbourhood in Jerusalem, hours after the military invasion of the Old City (and the West Bank, Gaza, the Sinai, and the Jawlan). In just a few days and nights, an entire Palestinian neighbourhood was destroyed. These bulldozers were again used in collective punishment and home demolitions in the West Bank and Gaza during the two intifadas, especially the Second Intifada, which saw massive demolitions in the Nablus and Jenin refugee camps, as well as in Rafah along the Egyptian border.

The text’s conclusion discusses the image of a Palestinian bulldozer on October 7, 2023, destroying part of the militarised siege wall around Gaza. This image stands in stark contrast to the images we’ve typically seen of Palestinian homes being destroyed. In this case, it’s the settler-colonial architectural structure itself that is being destroyed, marking a significant shift.

With this question, I immediately recalled a recent image where the Israeli soldiers, after emptying out a Palestinian home in Gaza, stole children’s teddy bears and stuck them onto their bulldozer. The D9 bulldozer is nicknamed “Doobi,” which means teddy bear in Hebrew. Genocide domesticated as cuteness.

It’s interesting that you bring up the counterimage. I was about to ask you about how you view this inversion. How do you see this tool, which was previously oppressing and now liberating, resonating with other anti-colonial struggles?

L: Something I fundamentally believe is that there is no architecture of emancipation. There’s no architecture that enables a person to transition from being oppressed to being a free subject. However, there is the opposite: a space where you enter as a free person and end up unfree. This is what we call a prison. And so while construction cannot be emancipative in itself, destruction carries an emancipatory possibility because, quite literally, you can destroy the walls of a prison.

I’m not suggesting that all architecture is doomed to serve oppressive regimes and that only destruction can set us free. Architecture can serve emancipatory politics; it just cannot enable emancipation in itself. Both construction and destruction represent a certain violence being applied by the same kind of forces against the same kind of communities. And we can use it as long as we understand what we’re dealing with. For some reason, destruction is usually more understood as something disruptive or violent. My work on architecture argues that we can harness the violence inherent in architecture—the violence of construction—towards our own struggles. It’s a more complex issue, but I believe it’s possible.

Shivangi Mariam, I wanted to ask about the poem that you use at the beginning of your article in which you weave these intimate moments of the day-to-day, such as the braiding of hair and haggling over produce like cucumbers, with these images of vast yet violent political landscapes. How do you see the intimate mode of poetry functioning within the political discourse on bulldozer demolitions and spatialised violence? How might moving away from conventional forms of writing or journalism help us resist and rethink these narratives of legality and order that we already see state actors imposing to fulfill their violent desires?

SM: That poem emerges from multiple sites of ruination and destruction, some of which I’ve witnessed firsthand, while others I’ve experienced as a secondary witness through screens. At its core, poetic language involves a practice of silence. We use words, but there is also the negative space of the gaps, which is why line breaks are so significant. These gaps reflect the moments of horror we witness that are unutterable and untranslatable. Destruction is not a singular event; it’s not simply a day when bulldozers arrive, destroy, and leave.

In the calculated process of reconfiguration of cities, bulldozers come much later. This violence has been embedded in the formation of the modern Indian nation-state itself, beginning with the British Raj and intensifying after the Partition, where the Muslim population was viewed with suspicion. In a newly independent India, Muslims were segregated into “Muslim Zones,” so as to maintain “communal order” and “harmony.” From the outset, why should certain communities bear the cost of upholding peace and the burden of maintaining order?

The first recorded instance of bulldozers being used against Muslims of India emerges from 1976, when thousands of homes were razed in the name of urban development in the Turkman Gate neighbourhood of Old Delhi. Because Muslims are constructed to be backward, lacking hygiene, and the ones practising segregation by confining themselves to these unsanitary spaces, beautification drive was used as an excuse to render them homeless. And during the 1990s, Bollywood and the media jointly dubbed Muslim-dominated neighbourhoods across the country as “terror outposts” unsafe for the general population, a threat to the nation and its secular order. So, through various constructive iterations, segregation and erasure have been systematically reinforced over the decades, gradually building the justification for bulldozers today. Now, over the past four or five years, their presence is a logical consequence of this foundational violence that we are taught to forget.

At the same time, Muslims of India have continuously affirmed their place in the nation-state, emphasising their sacrifices in the independence struggle and uprisings against British rule. Yet this historical link is being deliberately severed—they are told that they do not belong, reduced to the descendants of so-called invaders, “the offspring of the Mughals.”

This spatial violence is also a violence against history and a sense of belonging. We are being cut off not only in space but also in time. The home, a space of intimacy and safety, is destroyed, mirroring the historical segregation in the city itself. In Gujarat, for instance, as per the Disturbed Areas Act, real estate deals between Muslims and Hindus must be approved by the district collector of the area, and in several parts of the country, Muslims are explicitly prohibited from buying or renting a home. These ruptures break not just a sense of national belonging but also one’s connection to history and humanity—even to one’s psychic self. When these links are severed, language itself breaks down.

Much of what we experience cannot be fully expressed in words. This essay grapples with that loss of language—through theory, anecdote, and journalism. Sometimes, what we feel can only be conveyed through sighs, screams, or silence. Poetry, then, becomes a space to honour that absence of language. Erasure is the language of the state, and absence is somehow this poetic reclamation. In my home state, six martyrs recently died defending an old mosque from being bulldozed. These martyrs, like the mosques and homes lost, are not erased—they remain like a lump in our throat. Poetry becomes our act of maintaining a spectral presence amid the wreckage.

These homes are not just physical structures—they hold entire worlds. Within them are the lives of families and individuals: objects, photographs, books, artworks, and personal belongings. When a home is destroyed, these are not always retrievable.

I have two follow-ups—one specific to India and another broader in scope. Since you mentioned Gujarat, I can’t help but think about Ahmedabad, particularly because I took a summer course focused on the city. In that course, we discussed the formation of religious zones, but also the way Ahmedabad has been described as Modi’s playground of development. From the Sabarmati Riverfront project to the upcoming Olympic Park, large-scale urban projects have transformed the city. Do you think these mega-projects accelerate the alienation and displacement of Muslims in urban spaces? Are they directly incentivising such segregation, or is it more a byproduct of broader exclusionary policies?

SM: Yes, I think that perspective deeply informs how I view these processes. Léopold’s book, La politique du bulldozer, makes a crucial argument: there is nothing random or disorderly about ruination. It is a deliberate act, closely folded in architectural construction. I find this argument particularly relevant not only in India but also in Indian-Occupied Kashmir, which I expand upon in my research framed as architecture of ruin.

Let’s shift focus from Ahmedabad, which represents the ‘Modi model’—the same model under which the 2002 genocide of Muslims was choreographed. Consider instead Uttar Pradesh, specifically Akbar Nagar in Lucknow. Authorities announced a riverfront development project along the banks of the Kukrail river, and suddenly, all the homes in the area were deemed illegal constructions that had to be cleared. This led to mass displacement. Bulldozers surrounded the neighbourhood from all directions, backed by heavy police and paramilitary presence. This is the ‘Yogi model’ of spaciocide. Residents were beaten up and not even allowed to take back the rubble of their own bulldozed homes. We’re talking about a class- and caste-oppressed Muslim population, which is not even allowed to have the remainder of their home so that they can sell it to start life elsewhere. Who is this debris being sold to? To a Mumbai-based private firm that won the tender to earn profits over the rubble of these homes. So, this ruination is not mere abstraction nor is it limited solely to the ideological articulation of the majoritarian Hindu sentiment; there is a material profit that is extracted out of it as well. Maybe to construct another middle-class housing project or another dam or another deception of development. But why must one community have to sacrifice itself for the broader national good?

When we think of October 7, there’s a sort of moment that I found crazy where there’s a festival group that decided to host this leisurely activity directly adjacent to a tense colonial border. What is the importance of leisure in these moments of destruction or erasure, in desensitising individuals to them?

SM: With this question, I immediately recalled a recent image where the Israeli soldiers, after emptying out a Palestinian home in Gaza, stole children’s teddy bears and stuck them onto their bulldozer. The D9 bulldozer is nicknamed “Doobi,” which means teddy bear in Hebrew. Genocide domesticated as cuteness.

Just as development or beautification are used to sanitise and normalise violence, the idea of leisure lodges the bulldozer even deeper into the cultural landscape. In India, bulldozers are not just tools of destruction—they have become symbols to flaunt majoritarian triumphalism.

We see this in everyday life: toys shaped like bulldozers, T-shirts emblazoned with their images, and massive religious processions featuring tableaux with bulldozers. Recently, a photograph from Gujarat showed tourists sitting in the jaw of a bulldozer, roaming around the city. This pervasive cultural presence makes it difficult for people to associate bulldozers with their destructive role. Instead, they are celebrated as a protraction of majoritarian will—where not only is violence against minoritised or colonised communities carried out unapologetically, but it is also aestheticised and woven into public spectacle.

What is the role of mourning in countering not only spatial ruination but also the ruination of memory, particularly in keeping communities and their culture alive despite efforts to erase them?

L: We can think of two categories in this context: the destruction of a home and the annihilation of a home. Destruction leaves behind a ruin—what Shivangi Mariam calls an architecture of grief. A ruin tells the story of both its past existence and its destruction, preserving a memory of both. In contrast, annihilation leaves only rubble. In Palestine and India, we see this clearly: There’s only rubble being left. Sometimes alongside the trees of the forest, planted by the Jewish National Fund to dissimulate the former Palestinian villages being emptied and destroyed during the Nakba. In such cases, memorialisation becomes even more difficult, relying on whatever traces remain.

These homes are not just physical structures—they hold entire worlds. Within them are the lives of families and individuals: objects, photographs, books, artworks, and personal belongings. When a home is destroyed, these are not always retrievable. People often cannot even recover the debris of their own homes. The remnants—walls, partitions, ceilings—become intertwined with the objects that once made up daily life. Perhaps in this destruction, in what remains amid the wreckage, we can find a way to orient our mourning.

SM: One image is from Nai Basti in Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, where I spent some time last year. As far as the eye can see, the entire neighbourhood is reduced to rubble. Bulldozers have left behind nothing but destruction, yet people continue to live among the ruins because they have nowhere else to go. This is the reality for the dispossessed in India, particularly Dalits and Muslims, who have historically been landless. Their displacement does not begin with bulldozer violence—it predates it. Without access to formal housing, due to both legal and extrajudicial discrimination, many have no choice but to stay.

Even amidst the debris, makeshift shelters appear—tarpaulin sheets, thick cloth draped over broken structures. Many women I spoke to in Nai Basti told me firmly, This is our place, and we will not leave. Staying in the rubble is nearly impossible, especially in the cold, during rains, or with children who often fall ill. In some cases, it has even been fatal. There have been reports of deaths, including a child who was killed when a broken wall collapsed on him as he slept. Yet, despite the hardship, people refuse to let the present destruction define the future of their home. Let the government send orders again, they say. We will rebuild whatever we can, because this is where we belong.

In August 2023, Nai Basti in Mathura, Uttar Pradesh witnessed the demolition of more than 150 homes belonging to the caste-oppressed Muslim community. Photograph by Shivangi Mariam Raj, September 2024.

The second image that lingers with me is from the Mehrauli forest area, where one of Delhi’s oldest Sufi shrines, the 12th-century grave of Baba Haji Rouzbih, has now been destroyed. Imagine a bulldozer making its way deep into the forest, crushing a cherished history in its path. What struck me the most was that the khadim, the shrine’s caretaker, continues to move through the ruins with quiet determination. He carefully rearranges the stones, placing them in a particular order, restoring some semblance of how the shrine once stood—how he remembers it. He lights incense sticks amid the wreckage, lays rose petals and ittar, letting their fragrance mix with the dust of destruction. In this small act, he maintains his connection to the shrine. Erasure may be the language of the state, the tool of political forces seeking domination, but honouring absence—creating a relationship with what remains—is how we resist. It is how we continue to inhabit spaces that have been taken from us.

Do we simply resign ourselves to this order? Do we accept this cycle of ruination and normalise living within the wreckage? That would mean romanticising loss, turning survival into something passive. But resistance exists—active, defiant, and often unpredictable. There have been moments when communities in northern India have refused to watch their homes be reduced to rubble. They have set fire to the bulldozers that came to erase them. Cradled by the Aravalli mountains, Muslim communities in Mewat have taken up arms, fighting to defend their land and homes.

There is no single way to resist. Mourning takes different forms, and we have to accept them all. Some grieve in silence, others with action. Some turn to poetry, others to weapons. Too often, there is a false hierarchy imposed between violent and nonviolent resistance, as if one is more legitimate than the other. Both are expressions of the same refusal—refusal to disappear, to be erased.

Take, for example, the figure of the Palestinian bulldozer on October 7, where the very machine of destruction was repurposed into a tool of defiance, reclaiming agency over mourning, over loss, over how we resist colonial sovereignty. It is mourning with political force, an assertion that the people who have been shattered will not just endure but will fight to exist on their own terms.

In the settler-colonial framework in Kashmir and Palestine, we see a different dynamic than the one Léopold mentioned. The distinction between an armed combatant and a civilian in the occupied population ceases to exist—everyone is considered a threat. One is either an armed fighter, or one is aiding, shielding, or hiding an armed fighter. In this logic, every colonised body becomes a spatial blemish that must be cleansed.

At the beginning, Léopold, you mentioned a quote from Mohamed-Ali Berhouma: “Caterpillar is the same for both tanks and bulldozers.” I initially understood this literally—their moving mechanisms are identical, and they even sound the same. But beyond that, it raises a deeper question: What does “civilian” mean anymore? People who have long been citizens of a land are suddenly deemed non-citizens by the state. At the same time, tools that seem civilian—bulldozers, legal frameworks, bureaucratic procedures—become instruments of militarisation. The language bends to serve power. A home is declared illegal. A neighbourhood is labelled a security threat. A person is reclassified as an outsider. These shifts are not arbitrary, though they may seem so. Instead, they follow an internal logic designed to justify displacement and erasure. This is especially evident in places like Palestine and India, where legal and bureaucratic structures are weaponised against communities.

L: I think this is the very nature of the nation-state—it fundamentally operates by distinguishing between who is deemed a citizen and who is not. It doesn’t matter whether this distinction is applied to a foreigner or to someone who has lived on the land for generations. The principle remains the same.

The question of who gets to be called a civilian must be understood within this paradigm. The state is not just an abstract entity; it actively controls the forces of coercion—whether through the police, the military, or other institutions. But beyond that, people themselves become part of the state’s machinery—whether as workers within its structures or as individuals who align their interests with its policies. None of this operates without the participation of people who do not wear a uniform.

Does that mean the term civilian is no longer relevant? I’m not sure. It’s not a word I tend to use, as it’s primarily a legal designation—one paradoxically defined within the framework of war itself. In certain contexts, particularly settler-colonial ones, the more significant distinction may not be between civilian and non-civilian, but rather between those who are armed and those who are not—between those who actively participate in militias or enforcement structures and those who do not.

As for the bulldozer, I know you were asking about that specifically. But I think the same logic applies. None of these technologies are purely civilian. Even something as ubiquitous as the Internet has military origins. Whether or not the bulldozer emerged directly from a military framework, it functions today as a weapon. It is a machine built for destruction. As Mohamed-Ali Berhouma puts it, whether it’s a tank or a bulldozer, the mechanism is the same—the sound is the same, and in many ways, so is the effect.

SM: In the settler-colonial framework in Kashmir and Palestine, we see a different dynamic than the one Léopold mentioned. The distinction between an armed combatant and a civilian in the occupied population ceases to exist—everyone is considered a threat. One is either an armed fighter, or one is aiding, shielding, or hiding an armed fighter. In this logic, every colonised body becomes a spatial blemish that must be cleansed.

“Bulldozer justice,” a term that has gained popularity among Hindu supremacists in India, is, in fact, deeply legal. It may seem extrajudicial, but it is a retributive form of justice that operates within the structures of the law. Upon closer examination, we find that often the police assist mobs in attacking Muslim neighbourhoods, paramilitary forces accompany bulldozers and terrorise residents, and courtrooms lack adequate judicial mechanisms to address these demolitions: they do not serve as antidotes to this violence, they function as its extension. This is the fundamental crime of the nation-state: its legal system sustains fictions that we are compelled to believe in, presenting certain forms of violence as legitimate while condemning others. But ultimately, violence against certain communities—whether legal or carried out by non-state actors—remains embedded in the very logic of the nation-state that demands our obedience. Coming from our oppressors, there is no “better” violence, even if we are conditioned to see it that way. Law itself becomes an instrument of violence in the context of settler-colonialism; and our justice will never come from law.