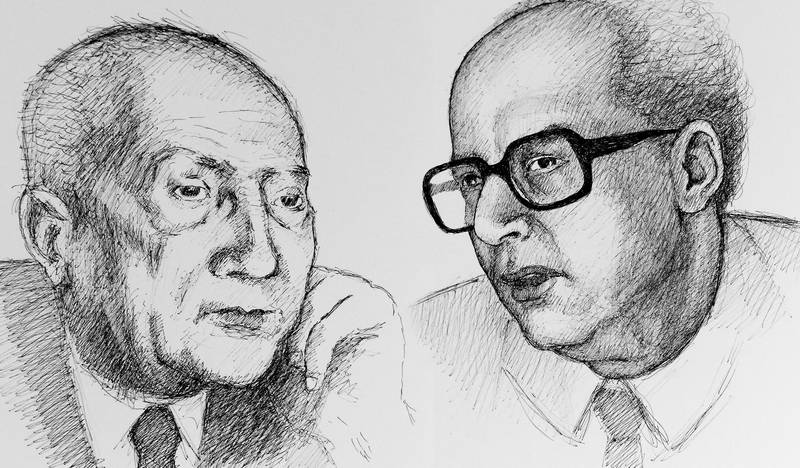

L to R – Salama Musa, Louis Awad. Illustration by Savu Korteniemi.

Ismail Fayed is a writer, researcher and curator based in Cairo. His interests span contemporary artistic and cultural practices, historical research and teaching the humanities. Together with anthropologist Fouad Halbouni he established the History and Cultural Memory Forum looking at historical narratives and cultural memory post-2011.

The recent fall of the Assad regime in Syria and the meteoric rise of HTS (Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham), led by Ahmed El Sharaa (formerly al-Julani), raised several alarm bells in Egypt and the region at large, as well as stirring an ongoing debate since the late 19th century as to what place religious minorities belong in a failed modern nation-state, specifically one where there is a Muslim majority.

Since the British occupation of Egypt, in 1882, the question and the status of the Copts became a contested issue, oscillating between archaic claims of the Copts being the legitimate descendants of the pharaohs, to refusing the existence of the Copts altogether as a religious other (that latter position is the official and not so official position of many of the Islamist revival movements of the past five decades1). The debates in Egypt, of course, did not revert to a century-old discourse, many cited a phenomenon as recent as al-Qaeda, as the ultimate manifestation of any political Islamist project, punishing women and annihilating all religious difference. The Egyptian Copts have always been thrown under the metaphorical bus of either conceding to corrupt political systems or risking the devastation of the angry masses. The last two hundred years bear witness to several incidents where political elites did just that2. It is an extremely precarious and treacherous position to occupy. The occupation of the British, made that position even more difficult, by trying to play out sectarian differences and stirring sectarian strife.

Many blame the Copts for their natural choice of safety above everything else. I can’t imagine having to choose between a military dictatorship (the current situation in Egypt right now) and the horrors of any Islamist project (what happened in Syria and Iraq is still too fresh in memory to be forgotten). But what happens when the Copts are not forced to choose between two horrific evils? What kind of worlds do they imagine?

In this essay I would like to look at the thought of two prominent Coptic intellectuals, Salama Musa (1887-1958) through his quasi-autobiography, The Cultivation of Salama Musa3 (1957) and Louis Awad (1915-1990) through his epic autobiography, Traces of a Lifetime: The Formative Years (1989)4. As some of the few Coptic intellectuals to acquire a prominent status among their peers and in their own time, and as Coptic intellectuals who did not belong to typically aristocratic backgrounds (the only social status that would allow Copts any semblance of power or access to resources), they both were quite unique in their unwavering progressive positions, with Awad being the more “liberally” minded of the two.

A Brief Biographical Sketch

The lives of both Musa and Awad span the majority of the late 19th C and the 20th century covering close to 120 years of modern Egyptian history. Musa was born to a middle class family with some means, in a province in the Delta and Awad was born to a typical middle class family in the south of Egypt, in Minya. Musa characterized his upbringing as being uneventful, he grew up fatherless, with a devoted, and devout mother, but was not educated in any particular religious sense. He was sent to study at both Coptic and Muslim kuttab (a quasi-elementary school where children learn basics of reading and arithmetic and principles of religion), and by his own admission could not read very well till we sent to an official elementary school run by a Coptic charity organization. Musa described his schooling experience as quite a negative and violent one. This was the height of the British terrorising the Egyptian population and expanding forms of control and surveillance that would lead to the uprising of 1919. Schooling was monopolized by the British, and schools were run as a military regiment. A fact that other Egyptian intellectuals of the time also bitterly complained about5. Musa would only get a slight reprieve when he embarked on a program of self-study, first in France (where he learnt French and later immersed himself in Parisian cultural life) and then London where he spent four years studying law and got heavily involved with Fabian Socialism. The Fabian Society and its intellectual atmosphere would exert enormous influence on Musa and his thinking (especially the ideas of Bernard Shaw and Havelock Ellis).

Awad had a slightly different experience, although not less violent. Awad was initially sent to a missionary French school, run by very stern, and equally violent priests, who took every chance to physically discipline the children. Awad speaks very negatively of the experience of corporal punishment and how it institutes forms of fear and subjection that can last a lifetime. Awad would eventually join a public school and speak of the impact of the 1919 revolution, detailing how politicized public life at the time was. We can sense from Awad’s recollections of his upbringing and education, a much more politically charged experience than Musa. On the other hand, in Musa’s recollections, a feeling of despair characterizes the period between 1905-1915, before and during WWI. Musa aptly described the position of the Copts at the time, being caught between a rising nationalist movement (exemplified in the struggle of Mustafa Kamil (1874-1908) and his nationalist party) that espoused an Ottoman/Islamic banner, which most Copts found politically and culturally repulsive6 and a British colonial administration that constantly used the Copts as a wedge and pretext to assert its control over Egypt.

Image of soldiers marching in 1915 is retrieved from the National Army Museum - New Zealand

Awad would refer to the way the British used the Copts to institute a policy of “divide and conquer”, and how, thanks to the very progressive thinking of his father and his uncle, he never really believed the propaganda of sectarian violence or threats against Coptic communities (not that such incidents didn’t happen, but what Awad describes is that in the everyday life of a small village in the south of Egypt, he rarely witnessed any sectarian strife of this kind. And not to the scale and degree the British used to publicize).

Both Musa and Awad tried to establish a career in public letters and in journalism, and both faced the harsh censorship of the monarchy and the British, and later on the Nasser regime in the case of Awad. Musa would rely for most of his life on the inheritance his father left him and would detail in his autobiography how little money he made out of his journalism.

In Awad’s epic autobiography there is a tender recollection of meeting Musa at the local chapter of the YMCA, Awad describes Musa as a hero and a “giant” of an intellectual, who introduced him to socialism and social realism in literature and in thought. From Awad’s description we get the sense that Musa was truly a modest man, of sharp intelligence and vast knowledge. There is a certain dignified gentleness and generosity in Musa, a certain openness and trust that is revealed through his writing, but also the writings of someone who was mentored by him, like Awad.

In the writings of both intellectuals, there are three aspects that I think are useful in trying to understand what positions two prominent Coptic intellectuals had vis-a-vis the extremely polarized landscape of pre and post independence. But also incredibly relevant to the political and social moment in Egypt, and the region as a whole. The three aspects show how two intellectuals belonging to a minority that historically faced varying degrees of oppression and marginalization, were thrown into the crucible of modernization (read: colonialism and capitalist integration into the world economy) and the limited political imaginary of their times and the ways they chose to articulate their subjectivities vis-a-vis a minoritarian status. Eliding questions of secularism and traditions in ways that are not only “incredibly contemporary” but also critical of Western so-called rationality and considerate of categories such “religion” and “religiosity”.

The cover of Louis Awad’s book Traces of a Lifetime

The cover of Salama Musa’s book Cultivating Salama Musa

Utopian Optimism

Towards the middle of his quasi-autobiography, Musa quotes the famed Lebanese literary star and pioneering feminist, May Ziyadeh (1886-1941), telling him that his optimism hides a deep internal pessimism. It is hard to see this pessimism in either Salama Musa’s quasi-autobiography and the epic autobiography of Louis Awad. Unlike Musa’s more personable and more humble recollections, Awad attempts nothing short of a complete history of 20th C Egypt seen through the prism of his own life growing up in the second decade of the 20th century. And yet both Musa and Awad, show a remarkable degree of utopian optimism that seems to place them at odds with the quite violent and in many cases deeply oppressive context they lived in. There is something uniquely democratic about the way both got introduced to and assumed a political and intellectual careers, an experience that shaped their personal but also intellectual trajectory. Both remained staunch democrats till the very end of their lives. In the sense that both Musa and Awad maintained a firm belief in the possibility of community and organizing within a community and staking a claim as a community. The civic aspect of their thinking and their work remained constant and consistent throughout the different political contexts they lived in.

And by utopian optimism, I mean an inherent belief in political possibility yet to come. Such possibility is not constrained by realpolitik, but remains aspirational even in the darkest of moments. Musa’s own recollection of how dire the politics of the early 20th C in Egypt was, from the brutal occupation of the British to the corrupt machinations of the monarchy, is balanced by his belief that Egyptian society can and is open to education and to go beyond the oppressive weight of tradition, occupation and exploitation (to Musa, all three are interrelated). Musa cites the public debates that were stirred when Qasim Amin wrote his The Liberation of Women (1899) and the need to reconsider the misery of middle class and upper class women who have steadily sunk into a social pariah status because of Ottoman norms and traditions7. While both Musa and Amin were heavily influenced by Darwin’s and Herbert Spencer’s ideas, and reading some of their ideas now might shock contemporary readers, writing in the late 19th C about the need for upper class women to leave the confines of the home and take off the face veil was definitely a cause for scandal back then. Amin’s writing and the debates surrounding his ideas, were definitely elitist. But Musa saw in them a particular opportunity to change public discourse about the way women are perceived and the way they are allowed to exist in the public sphere. A cause Musa kept advocating for, all his life.

Image of book cover of Qasim Amin’s Liberation of Women retrieved from Wikipedia (Arabic Language)

Musa’s utopian optimism, did not stop short at espousing and advocating a feminist position (he was one of the first Arab intellectuals to state that domestic work is unpaid labour8), it extended to attempting to establish a socialist party in 1921 (the project soon failed) and advocating tirelessly for agrarian reform to counter the devastating effect British policies had on Egyptian farmers and peasants (turning to monocrop farming, specifically cotton). As a modest landowner, Musa constantly wrote about the misery of the Egyptian peasantry, and the way patterns of ownership and land rental disadvantaged the average farmer. He wrote that the Egyptian farmer was twice exploited by the aristocratic elite (described as feudal overlords) and the British. He firmly believed that better agrarian policies have to take into consideration the ecological impact of monocrop farming (and this is in 1920s!) and to respect the biodiversity of the Egyptian countryside.

Awad as well saw a particular civic culture that was slowly taking root in Egypt over several decades, since the Urabi Revolt (1879-1882), and in fact both Musa and Awad, take that date, the date of the Urabi Revolt, as the moment of where their own family modern history begins9 and both give anecdotes as to how Egyptians rose in a moment of extreme authoritarianism and imperialist domination, to identify as a people with a claim. The idea of resisting despotic Ottoman-mediated rule (through the Muhammad Ali dynasty) and the French and British imperialism, and seeing all Egyptians as implicated in the same unjust reality, established an enduring sense of the collective. That experience would once again be affirmed by the 1919 revolution, in attempting to articulate a national identity that supersedes any other affiliation.

Of course this discourse, the nationalist movement discourse has been critiqued by many, and rightly so. Because the Copts were not one10, and there was definitely a distinction between the aristocratic class, the rest of the middle class Copts and Coptic peasants. What is interesting in both Awad’s and Musa’s experience, is not just the political slogans of a liberation movement. Both of them embodied an ethos of a citizen. Musa describes his life’s work as being busy with the interest of the people. And in another part of his autobiography, describes his life’s work, as similar to Socratese’s gadfly, stirring debate to alert the people and to stir the acquiescent11. The work of Musa as a mentor at the YMCA, his tireless advocacy through his writing, calling for a collective cultivation of consciousness rooted in progressive thinking and action (sometimes too much on the eugenic side, but that’s another story) was not just falling for an ideological program or sacrificing a minor identity for a fictional collective one. But rather a genuine concern for the emancipation of his fellow Egyptians.

In Awad’s life history we also see the citizen, rather than the Copt. And Awad goes to great lengths to show how Egyptian society in those years, between WWI and 1931 (when he joined Cairo University), was a crucible for political and social action. Awad weaves the history of that period (in quite obsessive detail) against his own formative years. He described the active sense of the collective taking root during the third decade of the 20th C, right before and leading to the 1919 revolution. Awad explains that the political foment of that moment engendered a sense of the collective that extended even to the furthest corners of Egypt (his own southern province included) and to social groups that normally would be excluded from such political action. Awad mentions the many ways school children participated in the political agitations of the time. Impulsively of course, and in many ways mimicking what the adults were doing, nonetheless with an idealism and honest belief that such actions would reach the unreachable capital, Cairo, and undermine the formidable foe, the British. The experience of identifying with a collective, taking action within a collective and projecting a possibility of change due to this collective sense and action is an enduring element in Awad’s recollections, even when he becomes cynical or weary from political disappointment or frustration.

1919 images retrieved from the website Egypt at the Manchester Museum

Musawar cover shows mourners commemorating the 40-day anniversary of 1919 Revolution Leader Saad Zaghloul at his mausoleum 1927

Alienation vs Integration

The second aspect that becomes apparent from the writing of both Awad and Musa, is the sense of alienation from a particular social group that is marked by its minoritarian identity. Musa repeatedly throughout his autobiography distances himself from the Coptic Orthodox Church and its traditions (calling them Byzantine relics12) while developing a much more “civic” form of engagement with the Coptic community, one that is premised on openness and degree of sociality that is absent within traditional coptic social life. The clearest manifestation of that is in Musa’s long career supporting the YMCA, giving talks, mentoring youth and promoting intra-communal dialogue. Musa never really subscribed to the ethos of “muscular christianity” that the YMCA advocated (he did however believe that physical activity and aesthetic regimens such as a dance cultivates the senses), but regarded the social and cultural spaces and the cultivation of practices of dialogue, exchange and collective doing, as crucial in creating modes of integration that are not identitarian and that can generate politics of action that is progressive and uplifting. This, of course, does not mean that Musa did not see the Coptic community as a community with a history and culture, quite the contrary, Musa saw that there was a longstanding connection between the Coptic community and Egypt’s long history. He had an enduring fascination with Ancient Egyptian history and was also one of the early advocates in claiming that history and finding ways to reconnect to this civilization heritage. That could be seen as the influence of Coptic nationalism, and this might be true. But nothing in what Musa did or wrote showed any political connection to Coptic nationalism or its overall vision. Musa remained thoroughly integrated into a political practice that was never premised on being a Copt.

Similarly, Awad also goes to great lengths to show his family were never particularly religious, nor close adherents of the church. Awad’s parents taught him and his siblings very basic tenets of Coptic christianity and sent him to Church on Sundays until he was twelve. After that Awad stopped attending church till he died. He wrote, saying, he would only enter a church for a wedding or a funeral. Awad believed that for many Coptic families of his social class and background (middle class, quasi-urban families), the issue of adherence to the Church was never mentioned or questioned. It never played a role in his life. In contrast to that, Awad talks effusively of his experience with the Muslim Youth Association, for example, in the late 1920s and 30s (before the Islamic revival movement undermined such kind of association – for context the Muslim Brotherhood was established in 1928 and didn’t really exert that much influence before 193613). He wrote how he attended several plays there, how there was a vibrant theatre culture thanks to the association and how, in one of the few times he stayed out late and, was reprimanded by his mother, was because he attended a play at the Muslim Youth Association and spent hours talking to one of the actors after the play ended.

Awad also speaks of his experience attending the YMCA and using its facilities and library and how it became a mentoring space for him, through the guidance of someone like Musa. Through those long conversations with Musa and others and by emphasizing that the YMCA did not restrict its membership to Christians only (there were Muslims, Jews, Baha’is as well), Awad credits this form of civic space and organization in acculturating him as a political and social subject. It was not only a learning space, but a space where those kinds of bonds became possible.

Literary Imaginary and the Possibility of Universalism

It is nothing short of a wonder, that both Musa and Awad credit literature as the key factor in introducing “other” worlds for them. Musa credits Western literature, first translated into Arabic and then later read in its original language, as the first possibility of seeing a world beyond the confines of his small village or the political despair of British Occupation. For example, he talks about Ibsen’s plays as the conduit through which he understood the predicament of the modern woman (in a Western context that is), citing how A Doll’s House (1879) helped him understand the limits patriarchy places on women and denies possibilities of autonomy and emancipation, and the need for women to rise from what he calls, femininity to humanity14. Musa’s reflections are rife with literary references that all contributed in helping him understand the inner workings of a human mind but also to try and imagine how that can expand to the context of Egypt.

Musa contrasts the literary imagination of late 19th C Western literature, the likes of Ibsen and Shaw with the literary imagination of his own contemporaries in Egypt. In one of the most scathing critiques in his book, Musa compares the kind of literary imagination that produces socialist and realist drama such as Ibsen’s and Shaw’s, to the literary imagination of someone like Taha Hussein and Abbas Mahmoud El Aqqad, that could only encompass the past and has no capacity to envision the future or even the present. Musa saw the literary imagination of two of his most prominent intellectual contemporaries as regressive and shortsighted. He believed such imaginary failed to embrace its nearer history (both Hussein and al-Aqqad were primarily classicists, who focused on early Islamic history and Classical Arabic poetry), it does not touch the issues of progress, the value of science and lacks all concern for current social and economic issues.

Musa shows a lot of fascination with (modern) Western literature and the possibilities it created, politically and socially. He saw that progress and understanding can only be advanced through cultivating this expansive literary imagination, stating that the objective of art (and literature) is humanity not beauty. Such imagination is borderless, and belongs to no one. He emphasized, repeatedly, that he is able to distinguish between Western literary imagination and Western imperialism. He gives the example of many of the intellectuals he associated with in England (the Fabian Society primarily) while he lived there, as being fundamentally opposed to colonialism. To him his anti-colonial struggle does not in any way infringe upon his deep appreciation of the Western literary imagination.

Awad also credits translated literature as a way outside the confines of the small town he lived in. He mentions with great fondness his father’s library and how this initial selection of English books were his gateway into another world and another time. It is clear from Awad’s recollections that he had a certain affinity to the written text and had quite a photographic memory, in not just recalling texts, but also in memorizing thousands of lines of poetry in several languages. It is through the literary imagination of Arabic poetry for example, that Awad is reconciled with Arabic culture and Islam. He indirectly writes about this in his autobiography, explaining that the emotive expanse of Arabic poetry, for him, went beyond the strictures of grammar, the religious demarcation and even the sense of alienation a Coptic school student might feel reading classical Arabic.

This is not just an overwrought claim, but an actual embodied effect of a particular literary imagination. Awad, through 600+ pages, frequently quotes again and again, Arabic poetry from across a broad timeline and many genres. The fact that someone like Awad can be very critical of the way Islam or religion has been used, and at the same time be remarkably open and appreciative and engaged with Arabic poetry in such a manner, is a clear indication that a certain kind of universalism is possible.

What life histories and reflections of both Musa and Awad can tell us, is that there is a possibility of thinking of the world, through literary imagination that is reconciliatory, open and that can be politically emancipatory. Neither showed any naivete about the political context where they are, and neither failed to show a very critical stance against colonialism, exploitation, authoritarianism, and all the political ills that plagued Egypt before and after independence. For them, the task of thinking had to start from an expansive intellectual imaginary, and this was not purely idealistic and was not politically inept. Both reiterate the need to think, but both believe it can never be done without that kind of imagination.

In a moment where massacres are happening throughout the region, perpetrated by occupying powers, but also by citizens against each other, the immense intellectual and humane impulses of Musa and Awad, reflected in long careers of service and advocacy, is a much needed reminder that minorities are not imprisoned by their social demarcation neither are they bereft of imagination. The force of life, Musa talked about so much, is rooted in that expansive imagination of the other. Both saw no other way.