Installation view, Maan läpi (Through the Earth), Gallery Augusta

Juha Hilpas works in video, writing and in contemporary art through various mediums of expression. His artistic work deals largely with material experiments in the context of mythologies, language and ”for the fun of it”. His works have been exhibited mostly in the Helsinki area, but have also been featured in various instances and events in Estonia and Croatia. Besides arts, he works to develop media content for finnish nonprofit organizations and has an interest in both fictional and non-fictional writing practices.

Taidekoulu MAA (henceforth MAA), a private art school in Suomenlinna, is a place that holds a special meaning for those (like me) who have attended it in the past. Just walking along the stone roads of the island brings me back to when I would migrate there daily, or semi-daily, depending on if I actually caught a ferry back to continental Helsinki the day before. Within the belly of this historical island, one was safe to explore and expand on what making art meant, and it’s not uncommon to find out that many established artists in Finland have done their time here.

I visited Gallery Augusta, to see Maan läpi (Through the Earth) – the final exhibition of MAA’s latest graduates. To write this review in a post isolationist time, it actually took me three trips to get my head around the exhibition, the feel of the island, the spring, and the memories. Especially after coming across a rumor that the independence of MAA and other private institutions like it are being threatened by cuts in funding. This review is a description of my trail through the exhibition, followed by ruminations on the situation that MAA is facing, based on a chat I had with MAA’s current principal, Minna Henriksson.

Maan läpi (Through the Earth) the final exhibition by the students of MAA. 15.4–1.5.2021. Gallery Augusta.

I sit in front of a blank white square. It is projected on the wall of Gallery Augusta, in Suomenlinna. For a moment, I wonder if the video is playing, if the art is on. Am I just too blind to make out what is happening on the white walls of this gallery on a sunny day? Then, little squiggly lines start to form. They crawl across the screen, like the ones on imaginary maps, leading me to X.

The words appearing on the screen are those of E.V.’s work, “Difficulty saying”. simple to the point. “That’s how ______”, “and it feels like______”, “If you have nothing good to say, say nothing”, followed by conversational phrases, conveying a need for social avoidance and distancing. Because I don’t know the exact context of these exchanges, I jump to the obvious and likely erroneous conclusions about These troubled times we live in (COVID). There’s a sudden embarrassment of my own tunnel vision in my interpretations. I scribble down notes about how the work signals a compulsion for disconnection and distances from one another, even without These troubled times we live in (COVID).

I haven’t been to exhibitions for a while, mostly because I’ve been experiencing growing indifference towards contemporary art. (Can indifference have a measure?)

That being the case, I am momentarily mesmerized by the messages while trying to decode them. I snicker, as they seem to point towards my own willingness to take distance from the plains of art. I make a careful effort to replace my complacent joy in this discovery with another wave of embarrassment. I remind myself that only moments ago I was ranting to a colleague about how self-obsessed contemporary art and artists are. And, as we can see, I am now indulging myself by writing about a young artist’s work from this first-person perspective.

To make amends, to repent and to recover some humility I decided to make an effort to remove myself and let E.V. welcome me to the exhibition.

Ida Lindgren, Submerged, 2021, installation, 16 mm film, mixed media

Ina Gabrielsson, Depths and Heights, 2021, series of five screenprints

On the right side of the projected image, hanging from the ceiling, a sheet of linen sways slightly from gusts of air as visitors pass by it. A visitor takes a moment to admire the delicate embroideries of plants and berries on it. Lit by the afternoon sun, they are pleasantly illuminated before the viewer. Audiences otherwise inclined find amusement from a wax seashell, or a snail, that has made its way across the pedestals. The snail has left behind a joyful trail of coily excrement. For some meaning to all of this, E.V. gives clues in the exhibition pamphlet. A recommended read if you’re not content to just enjoy the immediate materiality of these pieces.

E.V., Difficulty Saying, 2021, installation series

Poster art and prints should never go out of fashion, especially with their history in democratizing art and communication. These particular prints, like many other works in the exhibition, do solid work in inviting back a sense of wonder to the world and its phenomena, a sense that we at times might forget In these troubled times we live in (COVID).

On the wall opposite the video image, Ina Gabrielsson has presented us with a series of screenprints on paper. The prints titled Depths and Heights swing gently in mid-air, and much like the linen, they have a sense of lightness to them. These are printed images of chaotic scenes and bizarre creatures. Some members of the audience stop to examine their finer details closely, and again visitors’ movement through the air gives new life to the images.

At the opening of the exhibition, patrons of art were heard making comparisons between themselves and the printed beings. Your beloved editor of the NO NIIN magazine took the form of a deep-sea fish, and another aspiring writer who promised not to refer to himself anymore was judged to be like one of the more erratic forms presented in these poster-like images.

Poster art and prints should never go out of fashion, especially with their history in democratizing art and communication. These particular prints, like many other works in the exhibition, do solid work in inviting back a sense of wonder to the world and its phenomena, a sense that we at times might forget In these troubled times we live in (COVID).

Scrap aluminum, thick steel wire and chicken mesh coil into one another, forming Cycles by Anastasia Anikina. Putting a list of the materials in writing directly contradicts the lightness and movement Anastasia has managed to forge out of her scrapyard findings. The impressive structure towers at 2 meters high with little effort – its beams of steel wire more like light strokes of a pen. ‘Nature is never static; it is always evolving and creating’, declares the text for this work. Anastasia’s Cycles is a kinetic sculpture. With a twist of irony, at the time of this visit nature had decided to introduce the effects of entropy into the mechanical parts of her work.

Anastasia Anikina, Cycles, 2021, kinetic sculptures

E.V., Difficulty Saying, 2021, installation series

I (forgive the I), however, would not have guessed this, as there’s plenty of movement in the intertwining loops of metal as it is. As a confession, for more haptic people like me (sorry…), it is nearly impossible to not give the arching steel and aluminum coils a slight nudge. To see how they sway and vibrate hypnotically, again echoing the viewer’s presence.

Ida Tomminen, Viheriö (detail), 2021, installation

The next work, by Ida Tomminen, gladly invites the visitor to join in with their touch, even to lay on it. Viheriö, which loosely translates to the greenery is an installation impeccably executed on a foam mattress, with techniques familiar from Finnish Rugs, Ryijys. While laying down quite comfortably on a piece of art set against the wall, one can meditate on the joy we take in interactions with nature, plants and gardening.

To those of us who’ve had the pleasure of experiencing the caresses of green grass, of plant life and the abundance of clear water, it is a good time to remind ourselves that they are, in the end, privileged experiences, and should be appreciated as such. If I’m being totally honest, I utterly zoned out of thinking about this review while watching the screen on Ida’s installation, and now I just want to buy some cacti…

Moving on.

A corridor leads us to a darker area of Gallery Augusta.

Saija Vihervuori, RETRACE/MENTAL EVOLUTION, 2021, drawing installation

Saija Vihervuori, RETRACE/MENTAL EVOLUTION, 2021, drawing installation

Installation view, Maan läpi (Through the Earth), Gallery Augusta

Installation view, Maan läpi (Through the Earth), Gallery Augusta

Ratrace/Mental Evolution is an installation of drawings with ink, pencils and markers on plastic and paper. They form a tunnel illuminated by a video projector. A cone, or rather a tube of delicate lines, landscapes and animals, shoots out a stream of light that explodes into abstract shapes on a wall opposite the projector. Judging by the exhibition text, Ratrace points towards the artists, Saija Vihervuori’s, previous life as a landscape architect, and to her escape/evolution into artistry. Vihervuoris drawings set before us a coastal scenery with swaying grass, broken sand mounds and seagulls. For me, it is near impossible to experience the land, the earth breaking into the sea as anything but peaceful. While there is no sound in the installation, I still hear how the inky waters mold the shore. The voice, the smell, the noise of the sea. With each wave hitting the sands, the landscape is never the same, but the picture as a whole outlives us all. Even the birds.

It is evident that I was not unable to remove myself from this text for long.

No matter.

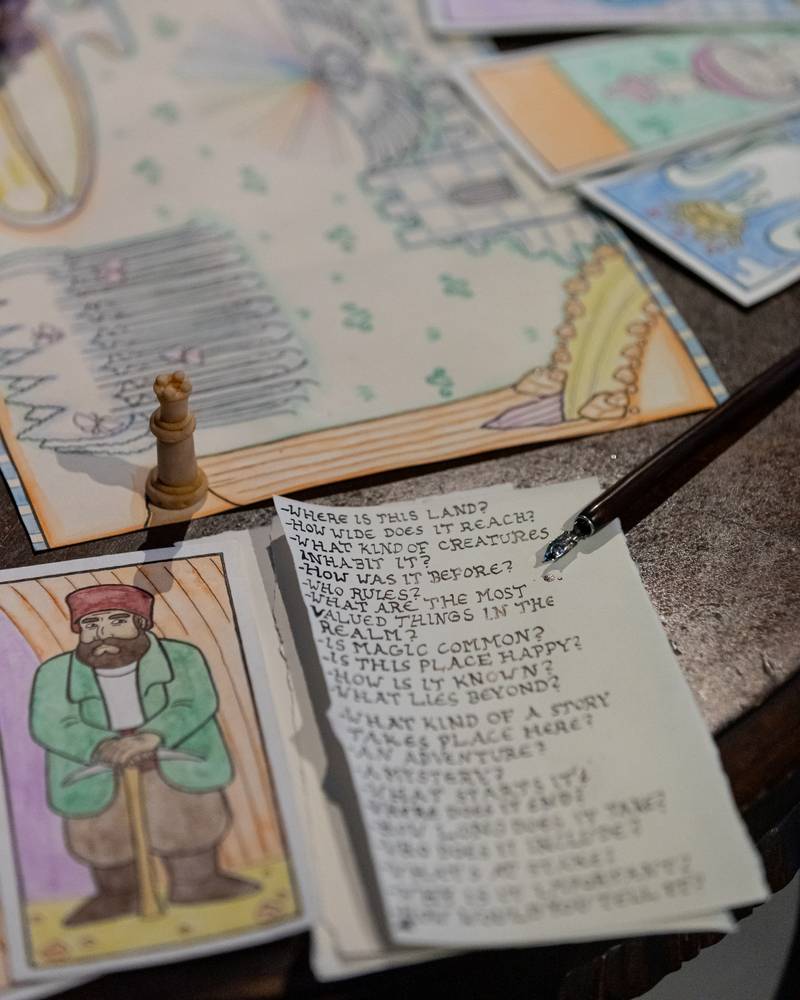

‘Is there rules to this game?’, is a note I’ve scribbled down among the cryptic poetries of the exhibition pamphlet. Antrei Riukula’s written entry in the booklet is more straightforward than most. They explain how they’re inviting us to sit down around a table covered with maps, tarotesque pictures of creatures, notes and a number of dice with strange symbols on them. The table has everything that one needs to embark on a journey like the one he has experienced with role-playing games. Notes on the table are written with quill and ink. They feature questions and suggestions of the nature of his imaginary world. I fiddle with the dice and pick up the pen before quickly reminding myself how it is often inappropriate to touch art. Pictures of creatures, reminiscent of tarot cards lay around a map of this world. We start picking our favourites again. Mine is the Goatboy.

Antrei Riukula, Imaginauts, 2021, installation

Antrei Riukula, Imaginauts, 2021, installation

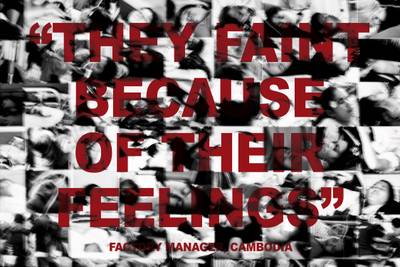

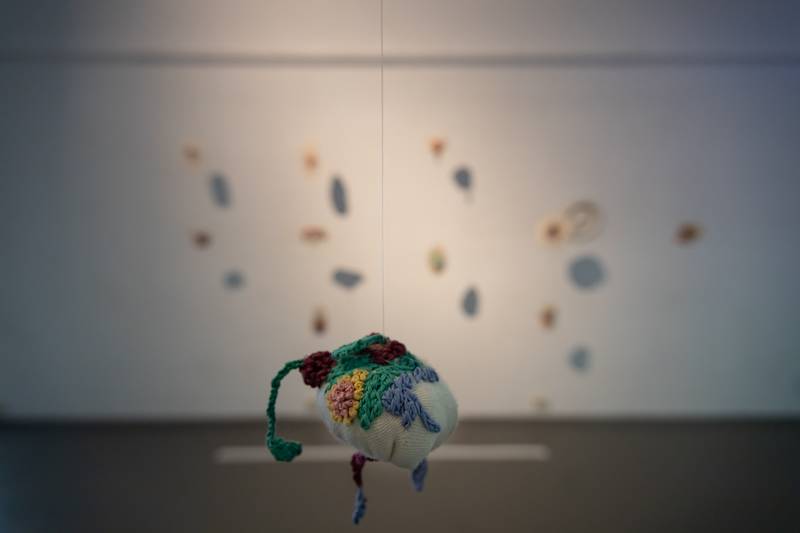

I love all manner of weird little creatures. Luckily there’s more behind me, floating in mid-air in front of an experimental 16mm film. They are part of Ida Lindgren’s installation Submerged.

As a fan of crafts, I should be more confident in stating that the weird critters, creatures and shapes hanging before me are crocheted with great care. If I’m mistaken by their technique, I beg for forgiveness. For me, they seem to be emerging from the film in which Ida is conducting all manner of corporeal experiments with matter, objects and penetrating the soil. Of the artworks in the exhibition, Ida Lindgren’s submerged addresses the exhibition’s theme, or title Through the earth most directly, with its tiny creatures emerging from the darkness of the room, as they are illuminated by the earthy warm tones of 16mm film.

Ida Lindgren, Submerged, 2021, installation

Stepping outside from the shades of Gallery Augusta, I appreciate the naive symbolism of the afternoon sun, in the first warm days of this spring. After experiencing lockdown and self-imposed distancing from the contemporary art world and events, Maan läpi (Through the Earth) feels like a welcoming, dare I say it… breath, full of enthusiastic takes on art and expression. Something I haven’t felt for a while, around the more established sects of contemporary art in Finland.

Full disclosure

I was asked to write this review on account of being a MAA alumni myself, graduating way back in 2013. While walking along the path laid in cobblestones, I try to put all of my memories of my time in MAA into a more current perspective. Those who’ve attended the school will likely remember the warmth of wooden floors of the old barracks building that serves as a nest and base of operations for most of MAA activities.

At the time I was studying there, I was experiencing fairly heavy phases of transitioning from one period of my life to another. Let’s say a transition from a state of being to a more sustainable one. I suspect that a lot of my classmates were going through something similar. In those three years, we shared a lot of joy, experimentation and even grief. Throughout it all, it didn’t seem to matter that much what your background was, or what your inclinations were as a human being. Many of us would have described ourselves as a bit of an outsider in our respective fields of life and on the subject of art, MAA tends to share some of that aura as an institution as well.

It’s tempting to write all of this off as some form of strange magic, with MAA attracting and caressing the odd in its stone belly, but to give credit where it’s due, a lot of what makes MAA is the result of its staff and teachers who were all professional artists. Headed by Bo “Isse” Karsten, who was MAA’s principal at the time, they had done an excellent job of creating an environment that was both open to all manner of free experimentation in life and expression, whilst still managing to foster a sense of safety. It was a free and safe space if you will. So free in fact that I probably still remember where the front door key can be found, in case I find myself stranded in Suomenlinna.

MAA differs from a lot of other schools in Finland also because it is a private entity and, as such, it is not strictly tied to the same format and curriculums as public institutions tend to be. This, coupled with the practical knowledge of teachers who are active in the fields of art, gives the education in MAA a unique perspective for their students to go on and conduct their business after graduating.

Now, Finnish politics dealing with culture and education has never seemed very straight forward or sensible to me. While visiting gallery Augusta for Maan läpi (Through the Earth), which exhibits the final works of all the latest graduates from MAA, a rumor reached me that MAA as a whole was currently under threat, due to having its funding cut off. I then had a brief talk about this matter with Minna Henriksson, an artist and the current principal of MAA. What I gathered from our discussion was that the rumors were true and are part of a trend in Finnish culture and educational politics dating back to at least 2018.

The basic idea behind this is the Ministry of Education and Cultures desire to streamline Finnish art education by gathering all of the various art schools in Finland under the bureaucratic and financial regime of the Ministry of Education. MAA has previously received much of its funding through TAIKE, who under Paula Tuovinen’s era as its head, has taken the stand that TAIKE should not be funding arts education, and focus solely on giving grants to professional artists and art organisations (other than educational).

As such, MAA has been basically given few options. Either merge with some of the existing institutions of arts education, adopt their curriculum and practices, find private funding or fade away.

It should be mentioned that mergers of art schools have a history of ending in full shutdowns. Remember Lahti Institute of Art, the Fine Arts program of TAMK and Kokkola Nordiska Konstskolan? Higher education in arts is already disproportionately focused on a single institution, whose professors are getting more and more tenure positions, narrowing the authoritative voice on how the profession of art is to be conducted.

I admit the role of private schools in the Finnish system can be a bit messy, as most schools are fully publicly funded and share their curriculum and politics. Still, I agree with Minna Henriksson when she states that by merging independent entities like MAA into the official structures of Finnish education, we risk experiencing a tragic loss of diversity in artistic ways of thinking in Finland. Unfortunately, the current trend is threatening to wipe such discussions away. Under the disguise of streamlining and efficiency, we are in danger of ending up with less and less people who get to decide what is art or how it should be interpreted.

We tend to often overlook the many other functions that schools and other such communities provide. As a small, even niche bubble of reality, MAA has over the years nurtured a sense of belonging and networking, especially for the younger students. This is an invaluable aspect in any effort to create a vital, dynamic scenery of culture in Finland.

On a brighter note, Henriksson stated that however the discussions between MAA, the Ministry of Culture and Education, TAIKE and any other parties/instances involved unfold, the conditions from which she thinks that it doesn’t make any sense to waver from—for it to continue to be Taidekoulu MAA (Art School MAA)—are: the right to choose what is being taught, who gets to teach and the right to choose their students. In addition to these the aim is to keep MAA’s tuition fees as agreeable as possible, as they are at 1200 Euros/year.

We tend to often overlook the many other functions that schools and other such communities provide. As a small, even niche bubble of reality, MAA has over the years nurtured a sense of belonging and networking, especially for the younger students. This is an invaluable aspect in any effort to create a vital, dynamic scenery of culture in Finland. Not to mention, small private schools like MAA have since the beginning employed countless working artists, who then can share their experience and knowledge, perhaps more freely than in the bureaucratic settings of the more established hierarchies of education.

MAA was a period in my life that still holds importance to me to this day, and I know many others who feel the same way. I do have faith in MAA’s staff members and in their resolve to keep MAA as a living entity within Finnish art scene. Meanwhile, the rest of us should do our best to keep these discussions alive and do our best to give our support to them and other independent actors within the narrowing scope of the cultural narratives floating around. Almost ten years have passed since I did my time in Suomenlinna. Still, when I meet someone who has attended MAA, I make a knowing nod to their direction, followed by a sting of spoken memories about the school, the space, the Space and teachers. Which is a sense I hope all their newly graduating students share as they are welcomed back into the world from that strange and comforting belly of Suomenlinna.

And again, congratulations to the artists Anastasia Anikina, Ida Tomminen, E.V., Ina Gabrielsson, Ida Lindgren, Antrei Riukula and Saija Vihervuori.

Installation view, Maan läpi (Through the Earth), Gallery Augusta