Jonas Staal, Climate Propagandas Congregation (2024), BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht. Photo: Ruben Hamelink

Sumugan Sivanesan is an artist, researcher and writer currently based in Berlin. His interests include: music, minority politics, activist media, artist infrastructures and more-than-human rights.

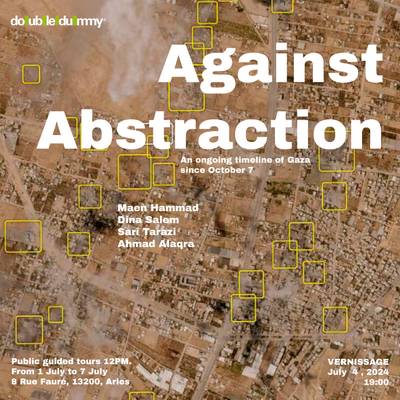

Over two days, Climate Propagandas Congregation brought together theorists, artists and organisers involved in struggles around the world to present on ideas raised in artist Jonas Staal’s recent book, Climate Propagandas: Stories of Extinction and Regeneration (2024). In it, Staal identifies and analyses competing climate propaganda, grouped according to their ideological attributes: “Liberal”, “Libertarian”, “Conspiracist”, “Ecofascist” and “Transformative”. Climate Propagandas was co-published by MIT Press and BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, an organisation in Utrecht that triangulates politics, activism and aesthetics across a range of practices, including visual and performing arts, theory, publishing and pedagogy.

I first encountered Staal through the New World Summits (NWS), which he launched in 2012—alternative parliaments staged within visual arts and theatre contexts featuring non-state actors. Inspired by Brechtian theatre and Occupy movements, NWS makes spaces for democratic assembly. Notably, in 2015, NWS was commissioned to design and build a public parliament in Rojava, the Kurdish “stateless democracy” in northern Syria, completed in 20181. A version of this architecture is now part of the Van Abbemuseum’s permanent collection in Eindhoven and continues to host gatherings.2

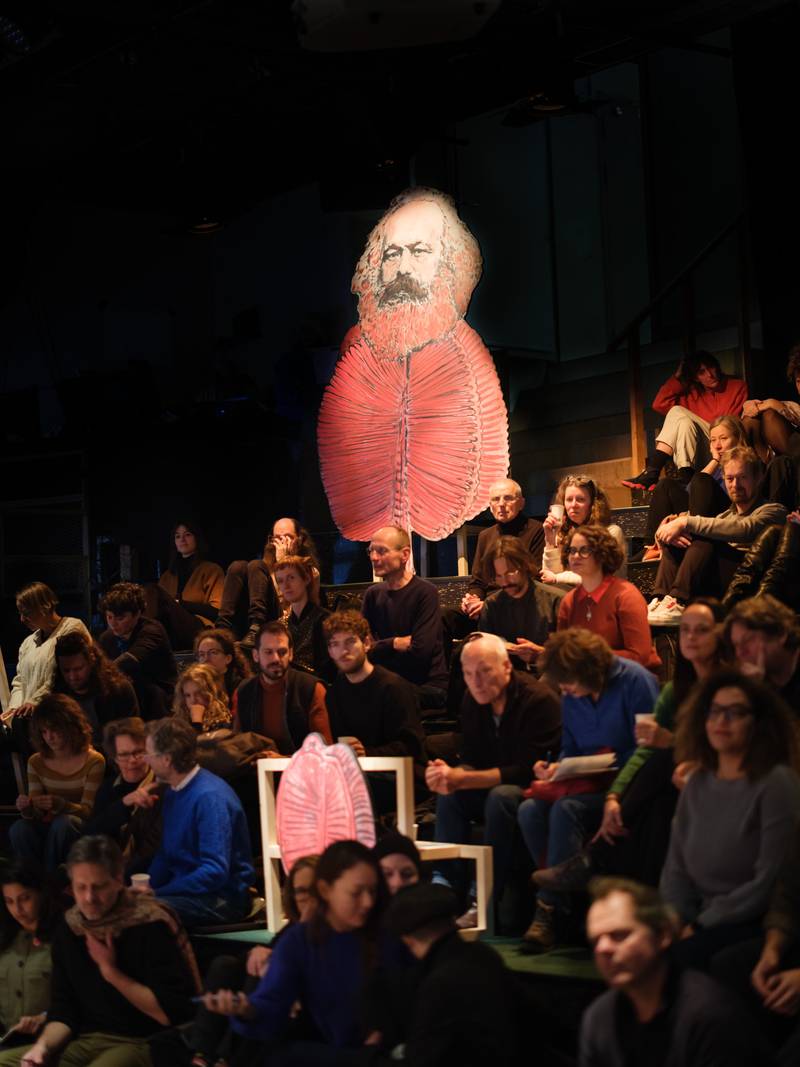

Jonas Staal, Climate Propagandas Congregation (2024), BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht. Photo: Ruben Hamelink

Continuing Staal’s practice of staging political assemblies, Climate Propagandas Congregation occurred in BAK’s auditorium among a diorama of “ancestors”; large cut-out chimeras propped up on wooden stands. Based on paintings made by Staal, these fantastic characters featured the heads of leftist icons, including Karl Marx, Rosa Luxemburg, and Ho Chi Minh, grafted onto the bodies of complex organisms that were dominant in the Ediacaran period (635 million to 541 million years ago). This geological period, proposed by geologist Reg Sprigg in 1946 and eventually ratified in 2004, was named after the Ediacara Hills in South Australia, near where the trace fossils were found, and the word is derived from local indigenous languages. The period is notable for the non-predatory cohabitation of its dominant sessile species, neither plant nor animal.

Staal, alongside philosopher Vincent W.J. van Gerven Oei, are developing a field of “proletarian geology”, contracted as “proletgeology”, to read the symbiotic relationship between these underwater creatures as a “proto-socialist ecology”. A short video, 94 Million Years of Collectivism (2022) opened the Congregation and the following day, van Gerven Oei closed the gathering with a lecture about this peculiar field of study, contextualising the represented interacting collectivist movements in deep time.

Rhada D’Souza, a professor of international law and collaborator with Staal on The Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (CICC), opened her lecture on “Liberal Climate Propaganda” by highlighting a notable absence in the diorama: Mao Zedong, founder of the People’s Republic of China and CCP chairman of the Chinese Communist Party. She recalled Mao’s appearance at the Conference of World Communist and Workers’ Parties, Moscow, November 1957, where he was asked by a journalist if he had been brainwashed. D’Souza elaborated on Mao’s response that it is beneficial to wash one’s brain regularly to get rid of ideologies that have been imposed by imperial education, to which I would add governmental regulations, industry pressure, advertising, and social media influencers. This idea of cleansing the mind from harmful propaganda resonated throughout subsequent discussions.

Rhada D’Souza: Jonas Staal, Climate Propagandas Congregation (2024), BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht. Photo: Ruben Hamelink

The congregation rejected the modern rationalist nature-culture divide in favor of “more-than-human” modes of thinking—embracing indigenous ontologies, feminist science thinkers like Donna Haraway, and the academic field of Environmental Humanities. This concept expands personhood and agency beyond living beings to include inert objects. US political theorist Jodi Dean, who described herself as a “communist object”, expanded on the “comradeship” between humans and things. She referenced “Sinwar’s Stick”, a meme derived from a video released by Israel Defense Forces in which Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar threw a stick at a drone before he was presumably killed.3 This final act of defiance spread across Palestinian solidarity networks and social media as a kind of counter-propaganda. Sinwar’s Stick can be juxtaposed with “David’s Sling”, Israel’s sophisticated air defense system named after the Biblical battle between David and Goliath, which Finland purchased in 2023.4

At the conclusion of the first day, Dean was in conversation with Julie de Lima, an elderly representative of the National Democratic Front of the Philippines, who has lived in exile in the Netherlands since 1987 with her late husband Jose “Joma” Sison (1939–2022), founder of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP). They observed how we in the so-called “Global North” have “internalised the neoliberal position” and come to regard ourselves as human capital and thus competitors rather than comrades. Discussing the Party’s efforts with land workers, farmers, and peasants for whom climate change is not propaganda but a lived reality, there arose a notion of “common sense communism”—of working collectively with land, ecosystems, and more-than-human entities as comrades.

Jodi Dean and Julie de Lima: Jonas Staal, Climate Propagandas Congregation (2024), BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht. Photo: Ruben Hamelink

Also present at the congregation were Isabelle Fremeaux and Jay Jordan from the unorthodox theatre collective Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination (Labofii). Since 2016 they have lived and organised at la ZAD (Zone à Défendre), an anti-airport occupation and semi-autonomous zone at Notre-Dame-des-Landes, France. Dean drew comparisons between Sinwar’s Stick and the field of batons that supporters of la ZAD planted there in 2016 after they fended off an eviction effort undertaken by militarised police, “Opération César.”5 This champ de bâtons is a monument and pact, as la ZAD supporters pledged to retrieve them if the occupation must again be defended.

At BAK, Labofii presented two performances, or rather rituals, proclaiming that: “Magic is not theory. It either works or it doesn’t!” On the first evening they distributed sigils drawn on paper that we then tied up with string and danced upon. A binding ritual, it sought to prevent Geert Wilders, leader of the far-right Party for Freedom, which is the majority in the Dutch House of Representatives, from doing any further harm. The following afternoon, we assembled around a large bushel of laurel leaves, hung like a pendulum from the lighting rig. The duo invoked the elements of earth, water, air and fire as they discussed la ZAD’s clashes with police in 2016. They explained how mud—a mixture of water and earth—was a comrade that bogged down police vehicles and that was hurled into their assailants’ visors, obscuring their vision in the dense forest and bocage surrounding the fields.

Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination: Jonas Staal, Climate Propagandas Congregation (2024), BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht. Photo: Ruben Hamelink

In Greek mythology, laurel or Daphne is affiliated with the deity Apollo, who is associated with the Sun. It became a symbol of victory when adopted by the Roman Empire and emperors (ironically “Caesars”) were often depicted wearing a crown of laurel leaves. Swinging the bound-up laurel branches between us, we sipped on beer brewed at the occupation and named in honour of a local species. As such, Labofii taught us to recall successes during difficult times and to imagine victories yet to come.

During the congregation b.ASIC a.CTIVIST k.ITCHEN, a community kitchen network and an essential part of BAK’s infrastructure that was run by La Cantina Sciocchina, served substantial vegetarian meals alongside coffee and tea to the faithful and hungry. An opportunity to socialise and recharge between sessions, meals also kept the congregation together. Attendees were asked to donate to the Gaza Soup Kitchen and to Sea Shepherd’s Operazione Siracusa which patrols the Plemmirio Marine Protected Area.

b.ASIC a.CTIVIST k.ITCHEN: Jonas Staal, Climate Propagandas Congregation (2024), BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht. Photo: Ruben Hamelink

During one of these breaks I found myself chatting with D’Souza, who reminded me that “we all come from places of genocide”. As I was raised as part of the multicultural settler-colonial majority of so-called Australia, where we are so inured to the genocide of Aboriginal people that it is like breathing air, this rang true. Then, having studied the genocide of ethnic Tamils in Sri Lanka at the conclusion of the civil war in 2009, I was struck by how the military and political tactics being deployed by Sri Lankan Armed Forces then were similar to those being used by Israel Defence Forces in Gaza following Hamas’ operation Al Aqsa Flood, 7 October 2023.6 Over time, I’ve become interested in how the international crime of genocide is strategically used to serve political-economic—let’s say neocolonial—interests, often under the guise of eliminating terrorism.

I took D’Souza’s quip as not being intended to normalise genocide but rather to remind Europeans that genocide is not exclusive to the Jewish experience and that there are international legal processes in place to deal with it. The problem arises when states conspire to obfuscate, hinder and block these processes, especially states like Germany, who are among the architects of these laws.

In Germany, many are sensitive to how the genocide in Gaza is brought to bear on other German genocides, notably that of the Ovaherero and Nama in Namibia between 1904 and 1908, the first genocide of the 20th century. Recently activists have drawn attention to Germany’s culpability alongside other EU states in the humanitarian crises afflicting Southern Sudan. EU states have supported programmes to control and restrict migration, investing significantly in the securitisation of Sudan’s borders.7 Researchers on the ground claim that Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF), one of the main military factions accused of war crimes, were strengthened by these programmes, notably the Khartoum Process, although EU representatives deny that the militants are direct beneficiaries.

Political scientist and genocide scholar A. Dirk Moses notes that his German peers often portray the Second Reich’s colonial violence as “limited and pragmatic”, justifying it economically, while framing the Third Reich’s ideological genocide of European Jews as a unique “Zivilisationsbruch”—a break from civilisation—beyond comparison with other coordinated mass killings.8 Around the world, scholars of critical race are flustered with their German counterparts for refusing to examine the links between these genocides and their ongoing legacies, frustrated by their reluctance to critique Israel for fear of being labelled antisemitic under German law.

So, I took D’Souza’s quip as not being intended to normalise genocide but rather to remind Europeans that genocide is not exclusive to the Jewish experience and that there are international legal processes in place to deal with it. The problem arises when states conspire to obfuscate, hinder and block these processes, especially states like Germany, who are among the architects of these laws. For example, since the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague issued an arrest warrant for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu last November, leaders in Germany—the biggest democracy in the EU—have indicated that they would not comply.9 Perhaps then, it comes as no surprise that the states that designed these laws are adept at finding ways around them.

The congregation marked BAK’s final event in its current form. After over 25 years of fostering “theoretically-informed, politically-driven art and experimental research,” BAK was defunded in 2024 by both the City of Utrecht and the Dutch State. Newly appointed artistic director Jeanne van Heeswijk vowed to persevere, even suggesting they might “squat the building” if necessary. Days earlier, BAK announced it would offer its publication archive for donations to ensure their continued circulation. Among the titles on offer, Propositions for Non-Fascist Living: Tentative and Urgent (2019), featuring contributors like Jumana Manna and Eyal Weizman, founder of Forensic Architecture, seemed notably relevant.

At the book stand, I also came across a copy of Ana Teixeira Pinto’s essay, “Shrinking Horizon: The German Struggle Against Universalism” (2024).10 Originally published for Third Text’s online forum “Thinking Gaza: Critical Interventions”, it appeared on the table as a hand-bound risograph-printed pamphlet produced by CUTT PRESS at Hopscotch Reading Room, Berlin. A cultural theorist and writer living and working between Germany and the Netherlands, Pinto’s text is a useful explainer for many of us Ausländers who are bewildered by Germany’s response to the war in Gaza. Since October 2023, we’ve learnt that Israel is an ideological pillar of the contemporary German state—its Staatsräson. While not a legal statute, right-leaning politicians want to make applying for German citizenship conditional on pledging allegiance to Israel,11 and Staaträson is currently being cited in Berlin to deport foreign residents involved in pro-Palestine actions.12

Berlin is home to a significant community of Palestinians who have settled here over generations fleeing Israel’s oppressive measures, and their presence is at odds with the position of the German state. Subsequently, Berlin’s cultural and intellectual community has been rattled by the cancellation and intimidation of Palestinians, alongside the policing and silencing of Jewish people critical of Zionism who are accused of not being aligned with “German sensibilities”. Nan Goldin’s provocative speech last November is understood to be a remarkable exception, proving that the Jewish-North American photographer is “too big to cancel”. At the opening of her major survey exhibition, Nan Goldin: This Will Not End Well, at Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie, she expressed her outrage about the “genocide in Gaza and Lebanon” and criticised Germany for conflating antisemitism with anti-Zionism. As the majority of attacks on synagogues and Jewish sites of significance in Germany are carried out by neo-Nazi groups, the same groups who terrorise Muslim, Turkish and Arab communities, it would be pertinent to heed the advice of anti-racism scholars and emphasise the connections between anti-Jewish and anti-Arab racisms in Europe.13

As we are coerced into normalising genocide in Germany, I wonder about the function of institutionalised art in this year of regression. In an exchange between Staal and D’Souza about the CICC originally published in Errant Journal (2022)14, D’Souza offers:

Today, art is the only small island left that gives the space for thinkers to think. Of course, art is also hugely commodified and there is a global art market out there. Yet, at a time when universities are closing down philosophy departments, when philosophers are called upon to produce practically “useful” knowledge, when the rupture with nature has alienated so many, that even many radical thinkers are often unable to join the dots, radical art offers the space from where new thinking can emerge about the big existential questions of our times.

In the early 2000s, when I first encountered the “art world”, it was caught up in “radicality”—radical pedagogy, radical philosophy, radical conviviality, etc.—which my peers and I concluded was a way of doing “politics lite”. We came to understand that contemporary artists were not so concerned with politics per se, but rather its representation in exhibitions, performance and discourse, and in a way that seemed to facilitate a liberal endorsement of critique. As Staal wrote in 2014, contemporary art had become a “form of a permanent critical questioning insulated from affecting the foundation of violent exploitation that sustains the capitalist-democratic doctrine.”15 More recently, I’ve noticed artists emphasising “professionalisation” and wonder if this marks a shift in trends, away from the aestheticisation of radical politics to instead insist upon the “pragmatics” of establishing and sustaining artistic careers under compromised circumstances.

Alternatively, Errant Journal, based in the Netherlands, recently published a manifesto by The Palestinian Pavilion, who urge their readers to consider that what is happening in Gaza will have consequences for us all. They call to us to use poetry and resistance to reject the “prevailing power” of technocrats, colonisers and corporations and to transform these imaginations into “affirmative actions”16, declaring:

Art is inherently political—in its message, production, and presentation. It engages with society, assuming a role either in complicity or resistance.

Having worked across art, activist, community, academic and commercial sectors, I know that professionalised artists do not have the monopoly on “creativity”. In Errant Journal, Staal also rejects the notion of the individuated “autonomist artist” to instead emphasise artists working in “a relational alliance with progressive lawyers, activists and emancipatory political leaders”, as it is only through collective organisation that the political imaginary can manifest as a political reality.17

With less public funding for the arts, as state offices succumb to the pressure of powerful corporate, industry and ideological lobby groups, and as states across Europe swing to the right, one can deduce that, in these challenging times, states will commission artists to uphold a façade of democracy.

So, while the political project of racial capitalism was democracy—or rather “democratism”, to use Staal’s revival of a term attributed to Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin18—it seems the political project of neoliberalism is the renewal of fascism. In Germany, we have witnessed the cancellation of exhibitions, art prizes, and awards based on the artists’ affinity for the Palestinian cause. Well-known examples include Jumana Manna, Candice Breitz, and members of Ruangrupa; the Archive of Silence keeps a public ledger of these incidents. The passing of the so-called “antisemitism resolution” by the Bundestag in November 2024, makes cultural funding dependent on applicants’ adherence to the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s (IHRA) Working Definition of antisemitism, which has been widely criticised for being too vague for such purposes, including by one of its lead authors, Kenneth Stern.19 Another concern is that decisions about applicants’ suitability are being made without public scrutiny, and many are anxious that state bureaucrats are effectively assembling a list of undesirable artists and watchwords, e.g., “lumbung”, the Indonesian word for rice barn that was the theme of ruangrupa’s documenta fifteen (2022). With less public funding for the arts, as state offices succumb to the pressure of powerful corporate, industry and ideological lobby groups, and as states across Europe swing to the right, one can deduce that, in these challenging times, states will commission artists to uphold a façade of democracy.

From provocative political statements, state narratives and institutional pressure to witness videos on social media, I find myself overwhelmed by competing propaganda—indeed, I wonder if there is anything but propaganda! So it is timely that Staal announces himself at the congregation as a propaganda researcher and artist. In his introductory address he gave a brief history lesson, recalling how the first office for propaganda was founded by Pope Gregory XV in 1622. The Vatican’s Congregatio de Propaganda Fide (Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith) task was to “propagate Catholicism” and counteract the Protestant reformist ideas gaining popularity across Europe. He acknowledged that propaganda got a bad name, associated with the mass brainwashing overseen by Nazi Germany’s Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, while reminding us that all political projects commit significant resources to promoting their ideas.

In the post-truth era, propaganda has become synonymous with Donald Trump’s “fake news” rhetoric to cast doubt on science and journalism to discredit his critics. “All I know is what’s on the internet,” he told NBC in 2016, spotlighting the influence of Meta, Mark Zuckerberg’s data empire. By 2022, Elon Musk had transformed Twitter—a popular platform for journalists and political spokespersons—into X, his personal propaganda tool. His debated straight-armed salute at Trump’s January inauguration signalled his alignment with far-right movements, particularly in Germany, where his Tesla electric car company has established a Gigafactory in Brandenburg, a stronghold of the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD). Musk openly endorses the party, using X to amplify its agenda. The convergence of Trump, Musk, and Zuckerberg makes clear how those who own the means by which information flows, shape the political imaginary.

Jonas Staal, Climate Propagandas Congregation (2024), BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht. Photo: Ruben Hamelink

Some are dismissive of Staal’s mode of “communist climate justice”, which arguably says as much about the success of capitalism’s “public relations” as it does about the demise of communist states. I’m also wary of those who romanticise the Soviet bloc, as I learn of postcolonial perspectives from the former USSR that I’m sure also resonate in Finland. Relevant aids for “non-fascist living” can also be gleaned from contributions to decolonial praxis by scholars, artists and activists from Ukraine standing against Putin’s aggression, who point out the blind spots of “western” analysis.20

Staal considers a range of internationalist, socialist and anticolonial struggles and during the congregation, he highlighted the “eco-socialist” efforts of Thomas Sankara, a revolutionary leader who was president of Burkina Faso from 1983 until 1987. An adamant Pan-Africanist, Sankara is recalled for advocating for women’s rights, installing literacy and vaccination programmes, and his criticisms of the World Bank. At the congregation, Staal foregrounded Sankara’s efforts to “make the Sahel green again”, emphasising how this effort of regeneration was one in which “comrade tree and comrade human needed to struggle side by side.”

Later, Andrew Curley of the Diné Nation and a representative of the indigenous Red Nation, Turtle Island (encompassing North America and Canada), spoke alongside Steve Lyons of US activist-art collective Not An Alternative and their institutional interventionist and revisionist programme, The Natural History Museum. Together, they discussed their initiative “Red Natural History,” which re-orients natural history—originally organised according to colonial, extractive, and capitalist interests—towards overlapping indigenous, socialist, and communist concerns that resonate with Staal and van Gerven Oei’s concept of “proletgeology”.

Jodi Dean: Andrew Curley and Steve Lyons: Jonas Staal, Climate Propagandas Congregation (2024), BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht. Photo: Ruben Hamelink

Andrew Curley and Steve Lyons: Jonas Staal, Climate Propagandas Congregation (2024), BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht. Photo: Ruben Hamelink

As Staal and D’Souza argue, one of the reasons to learn about propaganda is to be able to make better propaganda. So, it is worth noting that Staal hosted a propaganda training session at BAK as part of its “Making Public” programme. I am curious about what will come from these workshops to stimulate “transformative propaganda” and which institutions will support these and other artistic efforts to propagate a world that is just and equitable. Notably in April 2025, London’s Serpentine Gallery hosted Staal and D’Souza’s Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes where it put the East India Company on trial. While a degree of postcolonial critique is courted as evidence of cosmopolitan societies, such as the British UK, will institutions use their influence to pursue legal redress and reparations?

The suffocation of spaces for critique marks the political shift to the right in Europe, as initiatives founded to address inequalities, or indeed consider alternative political imaginaries, are defunded and dismantled. The notion of public intellectualism as a public good that ultimately benefits society seems to have been abandoned, while popular social media platforms have become a means of delivering finely tuned messaging, instrumentalising users and leveraging the interests of the “vectoralist class”21 who own them. As the critical arts sector adapts to the current challenging conditions, many will be paying close attention to Staal and BAK’s next moves.