Portrait of Amol Patil by Fransisca Angela

Pranita Thorat, a Mumbai-based writer, specializes in the intersection of caste and gender in her research and writing endeavours.

Amol K. Patil’s work addresses the harsh realities faced by the Dalit community, focusing on the lives of people living in Mumbai’s chawls and working as sanitation workers and manual scavengers. His sculptures, paintings, performances, and archival work strongly portray the deprivation of basic human needs – body, skin, touch, access to clean water, food, and land – and the brutal, animalistic existence they are forced to live in. He makes us see a community that remains invisible in the shadow of the city’s towering progress. By transforming everyday objects and spaces into powerful symbols of systemic injustice, Amol draws from personal experiences, family histories, and historical research to create a compelling dialogue about land, labour, and the enduring struggle for equality in Mumbai’s rapidly transforming urban landscape.

PRANITA: I would like to know more about the kind of artworks you have presented in your recent exhibitions, particularly the different objects you used to symbolise the reality of the caste system and invisibilization of the working class.

AMOL: This year, I opened two exhibitions, A Forest of Remembrance at Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) and The Shadow of Lustre at Röda Sten Konsthall. I had started a conversation with BAMPFA a year ago. Around the same time, I went to Mumbai, and my brother told me that the Crawford building where my father and grandfather lived would be demolished. Some of my brother’s friends were looking for a place to live in Parel, so my brother found a broker. Our surname is “Patil”, which is thought of as an upper caste surname, and maybe that’s why the broker was really nice with them and took them to show a flat. When he asked for one of my brother’s friend’s surname, he said “Kamble”. The broker suddenly said that this flat was not available. They were all shocked that he had just shown them the house, so what had happened suddenly? When they went home, the broker called my brother and said that we can’t rent the house to a lower caste person; it gets complicated for the housing society. Their buildings are getting demolished, and the people are not allowed to rent a place or buy any property because we are from the lower caste.

I thought I should use this whole conversation for the exhibition at BAMPFA, a sculpture that was reacting to an idea about these moving bodies in the past and present. If we see, these bodies have been here for a long time. In the 80s, a lot of people migrated from drought-hit villages to Mumbai for jobs in mills, cloth factories, and docks. It was a major hub for trade and industry at that time, but there was an issue of housing for the people who migrated. So the British colonial government built chawls, which we call BDD Chawls (Bombay Development Department), with around 100 sq. ft. and 32 rooms on a floor. These people had to fit in these tiny rooms where the entire family or group of workers had to live, with a shared bathroom and no airflow, no privacy. These people came from very different cultures, different ways of cooking food, and different colour tones of their houses. When you walk on the floor, you can see the colours changing, different smells of foods, and different ways of talking; it is all very dramatic and fascinating.

In a few years, these factories started shutting down, and the workers were not paid for years. They were stuck here, as going back to their villages meant debt and starvation, so they stayed in Mumbai, doing risky and low-paying work while finding a place to live and survive. Most of these chawls in Mumbai are being demolished now.

So, if you see this sculpture, it is more performative because the body is performing in this city. It is stuck, working, and moving simultaneously to find a place to live. One can also see that this is also a stuck relation with concrete, demolished bricks, dust, cotton mills, and sanitization places.

Installation view from MATRIX 286/Amol K Patil: A Forest of Remembrance at BAMPFA | Photo: Chris Grunder

Installation view from MATRIX 286/Amol K Patil: A Forest of Remembrance at BAMPFA | Photo: Chris Grunder

In Mumbai, chawls in different parts of the city are being demolished, and people are being sent to the outskirts of the city. Everything around the chawls is being developed – roads, corporate buildings, and bridges – but people’s homes are not being developed. Would you like to talk more about the themes of the body and the city that you use when addressing these issues and your understanding of them?

I started working on this idea during the Kochi Biennale in 2022, just before documenta. I started doing research and reading a lot. I found out about a wall in Tamil Nadu, in Uthapuram village, called the casteist wall. They built this wall to maintain segregation between the upper caste and the lower caste in the village. Because of this wall, the lower caste community had trouble using local transportation and accessing roads. After some protests, they broke a small portion, and the dominant caste people moved three kilometres away from the wall—it’s funny what they are doing.

Installation view from MATRIX 286/Amol K Patil: A Forest of Remembrance at BAMPFA | Photo: Chris Grunder

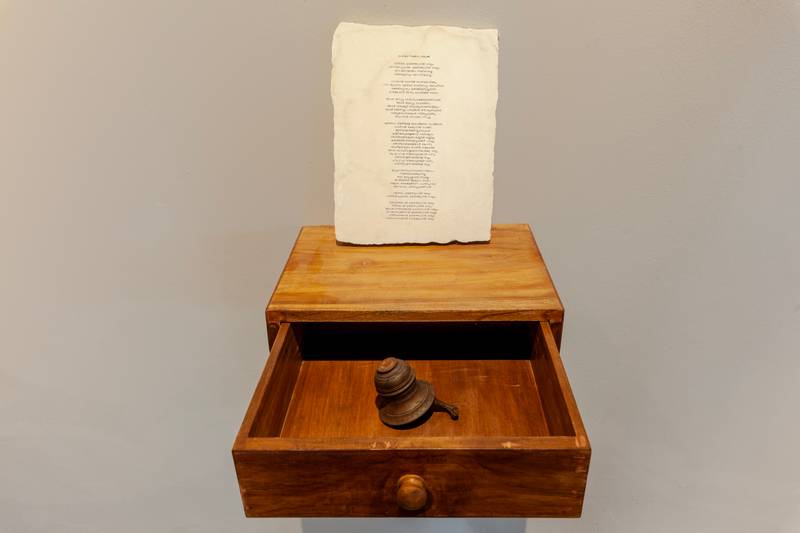

I grew up in Bombay, and I know that Bombay is also the same. So, I used this whole idea to make furniture – furniture moulds reflecting Bombay’s architectural spaces, the ugly buildings they’re constructing, the glass towers taking over labour lands. When they build new buildings, they make sure there’s a border. We are not allowed to buy property, even if we have money, just because we come from a lower caste. That’s the conversation I was making about the city and people occupying land, keeping documents of that occupied land in their drawers – that’s why I use the drawer, to transform a big landscape into a small one and to show how the body interacts with the land. The drawer represents how a bigger landscape is being reduced to a smaller one and how these bodies work every day in this society, literally cleaning everyone’s shit. Because of them, you’re actually surviving – they are supporting your environment. Our people are doing well, getting educated, finding ways to escape this kind of work. But those in higher positions are always there to push them down. No! You have to do this only because they come from the lower caste.

Installation view from The politics of skin and movement at the Kochi Muziris Biennale 2022-2023 | Photo: Kochi Biennale Foundation / Joseph Rahul)

Installation view from The politics of skin and movement at the Kochi Muziris Biennale 2022-2023 | Photo: Kochi Biennale Foundation / Joseph Rahul)

The initial generation who had to face all this in the city found different ways to support themselves. They built something for themselves through theatre, poetry and different art forms they created on their own. They also started engaging in artistic protest, and I think that’s one of the best things. It’s not just protesting; they’re creative, making beautiful banners and posters and using street art as a form of resistance. Like powada1, you know? I find it so interesting how they built this space for themselves and their creativity. Now, people from Crawford Market are travelling to the US and the UK for performances. We are enough on our own. We don’t need anyone’s help. We’re just fighting for equality, for freedom—that’s the thing.

And that, I think, is the conversation, too. It’s funny because the body is essential for survival here, yet no one talks about it. There’s no discussion about colour, blood, or the basic fact that a human is just a human. We’ve defined everything. We are racist and casteist, and the way we frame these conversations reflects that.

I am creating a conversation about lines, borders, how we build cities, and how the body interacts with space. Through touch and movement, the city becomes alive. It’s about how our bodies function daily in this society – not just working in different ways but improvising, adapting, and carving out new spaces for themselves. That is the whole idea about the body and the city.

Light is dominant and extensively utilised in your artwork, ranging from simple yellow bulbs to moving light in the sculpture. With light playing such a crucial role, how do you perceive the interaction of lights in your work?

Normally, whenever I install sculptures or drawings, I think of them as individual characters, each having a role in that specific space or gallery. For me, that space is a theatre, and these characters are playing a role. So, I use lightbulbs and spotlights to make the exhibition look like a theatrical space.

When it comes to the idea of “shadow of lustre,” it sounds very shiny, but I am using it as a reaction to create the opposite image since that work is talking about the manhole – a manual-cleaning site. When you look inside a manhole, there is black water, which is shiny, too. So it is a different reaction – an opposite one. Although this is scary and shiny, it is not that the people who clean it want to do it; they forcefully have to go in and clean. When you go in, there is only darkness, you cannot see anything, and when you are coming out, you start seeing the brightness slowly. I have kept a moving light so people can experience the same notion of light when they visit the exhibition. They cannot exactly know it, but it still creates some anxiety in the dark space, and then suddenly you see light.

The Shadow of Lustre” at Rijksakademie Open Studios 2024 | Photo: Amol Patil

I am fascinated by your use of simple materials like water, sand, and bricks. At first, they seem abstract or mundane, but for the Dalit community, they are resources they struggle to obtain. Can you describe the process of using these everyday objects to present the vast reality of a community?

The material I use heavily reflects my experiences and the scripts and poems written by my father and grandfather. I found my grandfather’s poetries around 2012 and I was surprised to see them – they were so loud and harsh. I also found a play written by my father, Saatha Patrachi Kahani. I was surprised; who could have thought about this in the 80s! It has minimal performance and amazing dialogues between a husband and wife. At first, it is just a conversation between them – the wife is in the village, and the husband has had to move to the city, and now they’re conversing through letters. By the end, it gets emotional and talks about how people are struggling in the big city. When I finished reading the script, I realised it is not an individual experience; it is a biography of a thousand people’s lives that he converted into one person’s story. It is one of my favourite scripts by my father.

There is one more script that talks about the cleaners working on the ground, which made me think about the relationship between people and soil. I didn’t get to spend much time with my father—he passed away when I was very young. But I remember how energetic he was about theatre, music, everything. Every May, he would go to our village in Konkan, where there was a competition among the villagers. There was a family from an instrumental music background – every year, they would have a competition between the father and son. They would sit on the land and keep a 500-rupee note in between. As they played, the vibrations from the music would move the note. Whoever’s side the note landed on won and got to carry the cultural tradition forward. I was around 10 years old, and I still remember the vibrations and the way they were playing so passionately. It wasn’t a fight for the money but a fight to continue their culture. That experience made me think about land and using vibration.

In 2013, I used this idea of land vibration to have a breathing land and use kinetic movement. These vibrations of the land are also the vibrations when a building is being demolished. The workers come a day before the demolishing, make a hole, and put water in it so it will be easy to demolish. Tiny bubbles keep coming from it – it feels like the people are still there. It feels like they came and built a graveyard for the people, but they’re still living, they are still surviving. That’s the image I wanted to create. In a way, the elements of the artwork are make-believe; it is a holographic video, but the protest is real.

It is so weird that the upper caste people are always lying. We did the Mahad Satyagraha and drank the water, but they will still purify the river by putting cow dung and urine in it. They say this will purify the whole river – are you serious? So I’m also lying to people, and that’s my work too – I want to lie, and I said it is holographic, but it is not. It’s a drinking glass, and there’s a cleaner in it who’s cleaning his body in the river. If you can put cow dung in the river, why can’t a person swim in that?

The Politics of Skin and Movement, at the Hayward Gallery, 2023

Your work depicts our reality in a poetic and performative way – it makes the audience feel the stories and experiences through materials, movement, and memory. What does this entire process of sharing your stories through art mean to you?

Since I started working in Europe, I have been travelling a lot, and my artwork is a medium to share and interact with people. My grandfather used to do powada, and it is an amazing art form. The practice is to write it in a way that raises questions and provides answers. These people would keep moving from one village to another, passing messages through their art form. In the last few years, I am just like them. I am taking all the conversations about my community and moving from one place to another. Sometimes, performing for a hundred days for new people who do not have any idea about the caste politics. My job is to share and pass on the messages.

I have this visual medium which I can show at different places to show how we are making our spaces. Art is a responsibility to represent my community, not just a conversation about suffering. The conversation is also about our past, present and future. In the past, we had Ambedkar, who started the conversation and was such a contemporary thinker. We are learning and changing, and we are conversing about our futures. I know I can’t change anything, but I have the right to see my future, and nobody can take that away from me. So, I keep improvising not only for my future but also for the sake of our whole community. We are finding our way by supporting each other. It’s not a protest but more about finding a way.

Black masks on roller skates, 2022 | Photo: Frank Sperling

Black masks on roller skates, 2022 | Photo: Frank Sperling