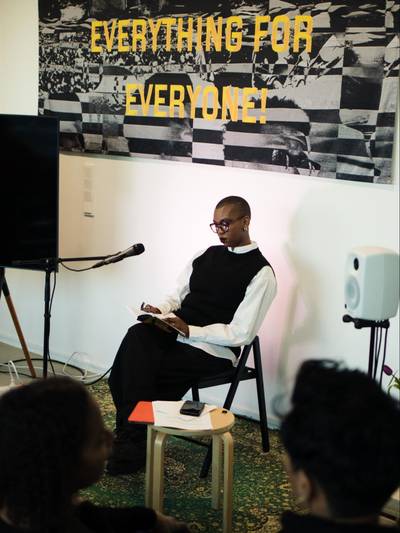

Lola Olufemi at SLOW Seasonal Laboratories for Other Worlds, Museum of Impossible Forms, Helsinki, 2025. Photo by Yelyzaveta Babaieva.

Anna Karima “AK” Wane (b. 1994, Dakar) is an artist, writer and curator currently based in Helsinki.

Dr. Lola Olufemi is a writer, researcher and activist based in London, UK. Her work involves studying archives of sociopolitical movements and imagining the otherwise alongside those who have come before. On March 21, 2025, Olufemi gave a talk entitled Clearing Space for the As Yet Unseen at the Museum of Impossible Forms in Helsinki. The following conversation makes reference to this talk as well as to Olufemi’s 2021 book Experiments in Imagining Otherwise.

AK: I wanted to begin by asking about your take on the archive. You asked the question, ‘do we need to know the past to know it or feel it?’ which made me think about Saidiya Hartman’s Venus in Two Acts, one of my favorite texts. I was wondering if you could elaborate on this notion a bit.

LO: In my work, I’m thinking with Saidiya Hartman to arrive at a point where the archive is not simply a site of restitution or rediscovery. One of the vital questions she asks in her essay, Venus in Two Acts, is: Are there textual practices that can function as modes of redress against the violence found in the archives? That question is central to her engagement with the archives of slavery. I agree with Hartman that things like critical fabulation, ways of engaging with archives, can help us undo the narrative totality that State archives impose, but I’m trying to use that method for myself. I’m interested in how engagements with the archives of radical social movements can provide us some strategic insight into their political demands.

One has to enter the archive with this ambivalence. You can’t necessarily imagine that the archive will give you a truth, because then you succumb to the same narrative totality that erases you or erases me as a black subject from the great timeline of History.

Often, when we find objects in the archive that have been produced by these movements, we read them as merely political documents. Basically, we fail to understand some of the artistic elements that their form, their style or their content give us. And I’m interested in examining the aesthetic qualities of those objects. There is a relationship between the visual, textual, sonic formality of those objects and the demands that are being made. So we can learn from their color design, the kind of language that is being used, and what this group’s sense of themself, of their politics, was, or how they organized, or whether they were communists, whether they were liberals, how they’re envisaging the future and futurity.

One has to enter the archive with this ambivalence. You can’t necessarily imagine that the archive will give you a truth, because then you succumb to the same narrative totality that erases you or erases me as a black subject from the great timeline of History. We can approach the archive, not seeing it as a container or marker of history, but as the protector of specific sets of objects which are acquired in and held through violent processes. It gives us another way of understanding what the material can do for us and others when we attempt to free it or unlock it through these creative modes.

AK: I liked what you said about approaching the archive with ambivalence. A few years ago, I went to France—to the colonial archives—trying, as you said, to look for the gaps, almost hoping to fill them. And I remember this moment, sitting there going through all these documents, and thinking: This is so boring. What am I doing here? It was all this very administrative, bureaucratic language that didn’t seem to represent anything. So I wondered, what’s the point?

LO: There’s also been a real archival turn recently for lots of artists or researchers. I also note that that kind of research can often become quite depoliticizing, because you take the text at face value, or you do this job of filling in the gaps. The reason why, in my practice, I’m so interested in the archive is because when I go in there and I engage with the material of radical social movement, my own capacity to imagine a different mode of social organization is shored up. I create an effective environment through modes of engagement which move me to actually believe that I am capable of making material political interventions in life and my work.

I never want the impetus to be part of a radical social organization to be divorced from the engagement with the archive. I’m not necessarily interested in the everyday lives and textures of black people in a specific location. I’m interested in those black people or political subjects that took up forms of radical, grassroots political mobilization and how they conceived of themselves. I’m interested in the future that I operate in as a researcher, looking back on this material, what kind of cross-temporal collaborations can I, as a researcher, create with the producers of these documents, whether they’re alive or dead?

AK: This brings me to my next question, which is, how do these things look in practice? What is the interplay of these theories with your lived reality? As you say, you’re digging and looking at the aesthetics of these political and social movements, and you’re trying to create this cross-temporal collaboration. How does this manifest within your work?

LO: It manifests in many different ways. I do many workshops with young people and workshops with organizers, where we engage with the material of radical social movements in a manner of archiving from below. So we think together about political strategy. We think about the conditions of a specific moment that creates strategies or formations, how that differs from the time that we exist in, and how it’s the same. Within those workshops, I also create moments of creativity that encourage participants to engage with any creative skills they possess. I’m a writer, so usually it’s textual. I get them to write back to the systems and structures that they live in. Or I encourage them to think creatively about how the world could be organized. Or I get them to think about the material interventions that they need to make in the landscapes that they exist in to bring about this change that we’re talking about. So there’s that.

My interest in aesthetics also influences my work in fiction. I’m a fiction writer. I write novels, and I write nonfiction as well. I’m interested in exploring the connection between aesthetics and political demand. So I do it there, but also mainly I do it through forms of political organization that I engage in. You know, as someone who belongs to grassroots groups and radical formations, I’m practicing the ethics that I’m trying to weave in my theoretical work practically: when I go to a meeting, when I engage in forms of direct action, when I help to plan those forms of direct action, or when I engage in forms of mutual aid. So for me, it’s a holistic way of understanding oneself as a researcher or a writer. I belong to a tradition of cultural workers who saw themselves as workers and who defined themselves as workers, crucially. Defining yourself as a worker enables you to understand the conditions in which your labor takes place, how your labor is exploited and why and who gets to make art and who gets to assign value to the art. My conceptualization of aesthetics follows bell hooks’ understanding of aesthetics as not just the theory of beauty or art, but as a way of seeing, and that’s what I think of the otherwise, as a modality that we use to confront the political crisis of our times.

A lot of organizers, a lot of people, find themselves in this pit of despair, which means that they’re unable to really understand that they’re a political actor with agency and that collective agency is the engine and driver of any form of social transformation.

AK: This makes me wonder, because you talk a lot about the language and about structural limitations to our imagination, what kind of tweaks or what kind of language you use in these organizing circles. How do you try to reword or reworld these notions so that you don’t also fall into the same schemas?

LO: That’s an interesting question. I was doing some reading today about the materiality of language. I belong to that school of understanding that language has material power. The way that it comes to interact with objects, bodies, and people imbues it with the power to actually change things, not on a systemic scale, but it creates the texture of our everyday lives and the modes of interpretation through which we understand social reality. So it’s a powerful tool in reframing the way that we engage, for example, with crisis. In the UK, the onset of neoliberalism has produced this effective stuckness in people. A lot of organizers, a lot of people, find themselves in this pit of despair, which means that they’re unable to really understand that they’re a political actor with agency and that collective agency is the engine and driver of any form of social transformation.

What I’m trying to do with the materiality of language in these workshop spaces, for example, is to get people to interrogate the effective environments that they build with their own language, to get people to rethink, reword, and reshape the timeline such that we don’t produce our own inability by saying things like, the left is not organized enough, or we’re not strong enough, or we’re not unified enough. In a way, it’s an attempt at eradicating what Sylvia Winter calls pre-nuclear thinking—this idea that we’re just careening towards a catastrophic failure. There has to be a narrative reworking of that in order for us to free up the space to believe that it will be possible for us to make certain interventions. We have to change the way we think about ourselves, others, and the world. Language has a core part in that.

AK: I have a question related to this. The question is simple, but not simple. I wanted to ask it because you brought it up in your talk, and it has been on my mind. And the question is simply, how do you refuse crisis?

LO: You’re right. That’s a simple, not simple question: how do I refuse crisis? A part of my research is the investigation of the ideological operation of crisis. I believe that investigation enables me to stop myself from falling into pessimism or idealism, because I understand that the conjuncture we are currently in wants us to believe there is no other way of organizing human life—that we have somehow reached the end of history, that the things we’re witnessing are so beyond our comprehension that we can do nothing.

But the atrocities that we witness are extremely comprehensible, and the process of tracking why and how they emerge across centuries and decades is an important analytical tool that enables us to frame and bolster our own resistance. If we know how the enemy operates, then we know how we need to operate. We know how we need to enact forms of community defense. We know where the sites of struggle will be. We know how to prepare the arguments that we need in order to move through fascist culture wars. So, for me, investigating the ideological operation of crisis and the notion of catastrophe, or the notion that the world is ending, and people’s attachments to inaction, is one way that I do that.

Another, on a more haptic and affective, creative level, is going into the archives. So much of my research for my entire PhD project came from the experience of going into the archive and, you know, holding an image of Sylvia Erike, or holding the first OAD manifesto, and feeling—on a very deeply bodily level, on an entirely non-rational plane—that somebody I knew wrote this, or that I was meaningfully touching the past and connected to what these people had written. Rather than dismissing that experience as merely affective or emotional, I wanted to give it justice. I wanted to see whether there was a political weight or a political grounding behind my feelings of connection to a past that I could not reach.

There’s this really good Wendy Trevino poem—I’m gonna butcher it—but she says: “when you’re engaging in any kind of struggle or political experience, it becomes very clear to you who’s on your side and who isn’t, and don’t waste your time trying to convince those people who aren’t on your side to be on your side. Look at the people who are around you, and fortify that.”

AK: I went to a panel discussion last year here in Helsinki about surviving as an international artist in Finland. It was a strange panel. Most of the ideas were to study business, and it was just this odd rhetoric. At some point, I raised my hand and asked about alternatives, knowing that these systems do not work. The moderator said to me, “Well, we all have to pay our bills. We don’t have time to reinvent the wheel.” And I just looked at that woman and thought, This is such a privileged position, because you can work within that wheel, but many of us don’t have that ability—and that’s why we’re trying to reinvent it. It was such a frustrating moment of realizing we’re not speaking the same language at all. How do you deal with these moments?

LO: In much the same way as you’ve just articulated—by trying to challenge them in the moment, but also being frustrated if I can’t. There’s this really good Wendy Trevino poem—I’m gonna butcher it—but she says: “when you’re engaging in any kind of struggle or political experience, it becomes very clear to you who’s on your side and who isn’t, and don’t waste your time trying to convince those people who aren’t on your side to be on your side. Look at the people who are around you, and fortify that.” That has been a major guiding maxim for me ever since I left university. You can spend a lot of time engaging with your enemy and trying to get them to understand you as a human being, but it’s more important in moments of crisis to fortify the pre-existing structures you have, to grow those networks through political consciousness raising, and to reach those who can be awakened—those who can be encouraged to think more critically—rather than the people who hate you. I think that’s a much more fulfilling political task.

AK: That’s interesting, because there’s so much talk about bubbles. It’s fascinating to engage with the people responding to it, of course—but at a certain point, do you start to feel like the folks just outside your bubble have no idea what you’re talking about?

LO: I find this concept of the liberal bubbles to be quite an interesting one, because it assumes that everyone in the world does not live in some proximity to people who think similarly to them. It can become a way to self-flagellate for no reason, and it’s underpinned by this assumption that the role of anyone on the left is to do the work of persuasion. I agree that it’s important to build mass movements through political consciousness raising, but not this idea that we must endlessly sit down and debate people whose minds can never be changed. For some people, the politics that we’re engaged in are just about a rhetorical exercise or a slick turn of phrase, rather than very serious political and ethical commitments that we’re making to the people around us. And if my commitment is to keep my community that is under attack alive, I’m not going to waste time debating the person that wants to kill me or flagellating about how I’m not reaching them. I’m going to ensure the community defense and safety of those people that are oppressed in my community. But I’m also going to ensure that I have resources like political education and consciousness raising, resources that can help me reach those people who are capable of critical thought, rather than those people who will never want what I want.

AK: I want to talk about finding balance. Recently, I have been thinking a lot about my grandfather. He was a politician and sportsman, and he worked for the community and the country his whole life. I am realizing that there’s a lot of similarities between us, but also thinking about the fact that he wasn’t able to be there for his family because he was busy, because he was building stuff. And so that’s something that’s been on my mind a lot because, of course, you want to work and you want to do stuff and run around and build community, but I’m also trying to ground myself and be there for the people around me. So I am wondering how to stay present.

LO: It’s always a delicate balance. When you read the memoirs or accounts of people who have been involved in political organization, personal relationships are often sacrificed. There are ways that it becomes impossible to balance the work of political organization with the demands that the world under capitalism places on you, whether that’s through your work, whether that’s through your familial commitments, whether that’s through your caring responsibilities.

I think of how many people are not able to be involved in social movements because of their own disability or their caring responsibilities, or the way that forms of social violence take away their capacity, or their ability to fight that social violence, because they’re simply trying to stay alive. So much of enacting the otherwise, as a modality or a process, is in the same way that abolitionist theory tells us to do. It’s about trying to pry apart organized violence from organized abandonment, trying to make political demands that affirm life in an environment where life is not only not being affirmed, but actively destroyed. What political demands would enable us more free time, more ability to connect with each other, more ability to see each other meaningfully, to have transformative gender relations, to remove violent apparatus from our lives and the way that we engage with one another? All those things free us up to engage in forms of political organization more and more.

I get there is always a trade-off, but I think so much about the discipline it takes to dedicate one’s life to the cause of freedom. When I’m tempted to fall back into pessimism, or whatever, I just think that for so many, it means life and death, and that’s a serious commitment that not many people are capable of making. It means that you have to sacrifice something. That’s a very humbling way of thinking about building the future, that level of sacrifice, but also that level of discipline, that level of belief. A lot of the work that I do is about fortifying structures of belief. I want people to move away from anything that I make or create or write with some sense of the affirmation of life, rather than the inevitability of its destruction.