Photograph of rooftops and antennas in the city of Pucallpa. © Arcaica ry.

Renzo Signori, artistic researcher and curator, directs the Koynē Program in Helsinki, exploring more sustainable materials and technologies. His work bridges art, ecology, and culture through immersive projects integrating biomaterials and digital media.

Pedro Favaron, PhD, is a Peruvian-born researcher, poet, and thinker. Together we spoke about language as a living technology, Indigenous cosmologies, and the critique of cybernetic modernity from a perspective rooted in Amazonian knowledge systems. His philosophical approach, deeply informed by the Shipibo-Konibo cosmovision, challenges the ontological foundations of the Western technological paradigm, proposing instead a “cosmoethics” that recognizes the subjectivity of all beings as the basis for an ethical relationship with the world.

The Shipibo-Konibo are an Indigenous people of the Peruvian Amazon whose spiritual, artistic, and medicinal practices are profoundly intertwined with a vision of the universe as a web of living energies. Their knowledge is transmitted through songs, visions, master plants, and symbolic designs that operate as technologies of healing and communication with the non-human world.

As curator of the Koyne Program—a platform for situated thought that intersects art, transmeridional exploration, and recycled technologies—I am interested in fostering dialogues that explore alternative perspectives at the edges of modern thought. This conversation unfolds with that intention: to build bridges between ritual practices, vibratory languages, and possible futures beyond technocracy, guided by respect, reciprocity, and a deep connection to life in all its forms.

Lagoon at the Botanical Garden of Pucallpa. © Arcaica ry.

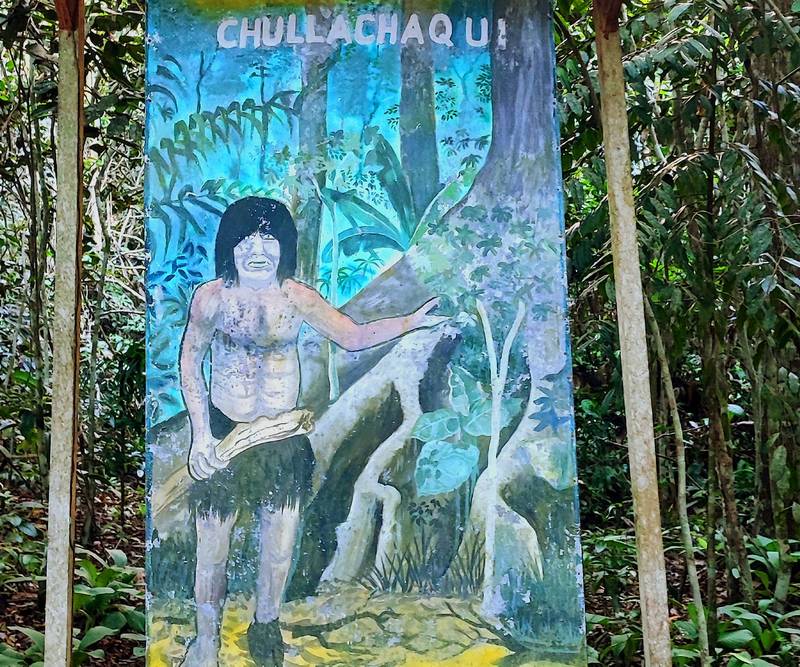

Photograph of a sign depicting a graphic representation of an Indigenous Amazonian figure in a natural park on the outskirts of Pucallpa. © Arcaica ry.

RENZO: Pedro, throughout your work, we can identify a critique of the contemporary technological paradigm. What is the starting point of this critique?

PEDRO: Yes. Together with a Canadian colleague (Keith Williams), we’ve been developing a critique of cyber-modernity grounded in ancestral knowledge – knowledge that is both interpreted and revitalized in the present. One of our central hypotheses is the existence of a sacred web of life: a profound, pre-existing interconnection among all beings that predates the Internet of Things. From this perspective, contemporary cybernetics is a technological project founded on an ontological distortion – it fails to recognize that all beings are already interconnected. It imposes a model of connection that obscures rather than reveals the already-existing interdependence of all beings. Instead, the sacred web of life entails a cosmoethic. It goes beyond ecological ethics (often framed within modern and materialistic moral or utilitarian terms) because once we acknowledge that all of existence is bound through subjectivity, consciousness, and spiritual breath, other beings can no longer be treated as mere objects to be manipulated at will. This shift challenges the instrumental treatment of the more-than-human world and affirms a form of accountability to all beings, not just as resources or data points, but as participants in a shared, sacred existence.

In that sense, do you see a link between ancestral Amazonian practices and contemporary phenomena such as virtual worlds?

Absolutely. Indigenous sages have long cultivated ways of navigating suprasensible realms – worlds in which one can exist in multiple spaces simultaneously. There is a meaningful analogy between these spiritual displacements and the immersive experiences offered by virtual environments. For centuries, Indigenous wisdom has developed a sophisticated expertise in inhabiting multiple planes of existence at once, an ability that can even be applied therapeutically to address contemporary pathologies. I once witnessed a difficult case in which a teenager addicted to video games was healed through the intervention of an onaya (traditional healer), who “entered” the symbolic world of the game to recover fragmented parts of the patient’s soul. The very possibility of virtuality is grounded in the human spiritual capacity to dwell in more than one ontological dimension at the same time. However, there is a crucial distinction between cybernetic virtuality and the spiritual displacements of the onaya: the former is often driven by entertainment, simulation, and consumption, while the latter is embedded in a cosmological and ethical framework that seeks healing, balance, and relational restoration. These journeys undertaken by the onaya require deep preparation and ancestral knowledge, allowing for responsible therapeutic engagement with altered states of consciousness.

Based on your experience with the Shipibo-Konibo nation, how is the idea of interconnection expressed in relation to dualistic categories such as nature/culture?

What’s particularly interesting is that, although the Shipibo language does make distinctions among beings, it does not do so through the irreconcilable dichotomies characteristic of Cartesian thought. For instance, joni designates a human being, but there is no single term that generically encompasses all “animals” in the way Western taxonomies do. If you ask an everyday Shipibo speaker how to say “animal” in Shipibo, they might reply joina. However, joina is not equivalent to the Western category of “animal.” A hummingbird, for example, is not joina – it is isá. A fish is not joina either – it is yapa.

If we interpret axe as “culture,” then culture becomes something distributed across all beings, not exclusive to humans. This reflective possibility undermines the human exceptionalism that underlies much of modern cultural theory.

Moreover, isá does not refer to all birds. A hummingbird is isá, but a hawk would be classified as joina. Turtles, interestingly, do not fall under any of these categories. There is fascinating work to be done here from the perspective of ethnobiology. I am currently developing unpublished texts in collaboration with the linguist Roberto Zariquiey, director of the Chana Scientific Station. He has conducted similar research with the Cacataibo people, and together we’ve identified an area that remains largely unexplored: the role of odors in Indigenous botanical knowledge.

In terms of the nature/culture divide, such a binary does not exist within the Shipibo worldview. The closest equivalent to “culture” might be axe, which could be translated as “custom” or “habit.” But upon closer examination, one finds that a jaguar also has axe – it, too, has customs. If we interpret axe as “culture,” then culture becomes something distributed across all beings, not exclusive to humans. This reflective possibility undermines the human exceptionalism that underlies much of modern cultural theory.

For example, jema means “village,” and ni means “forest.” While there is a kind of distinction between the two, the village cannot exist without the forest. And the forest, too, has axe – it possesses custom, memory, and intergenerational knowledge. So it’s not that there are no distinctions. All languages make distinctions; the very act of saying “you” and “I” already creates a difference. But in the case of the Shipibo language, these distinctions are not absolute or oppositional in the Cartesian sense – they are relational and porous. This suggests an alternative epistemological foundation for thinking about human and more-than-human relations. Also, a more inclusive cosmology in which beings are interconnected through custom, memory, and reciprocal relations.

Regarding the notions of good and evil, how is that dualism applied in the Shipibo-Konibo cultural context?

In Shipibo, terms like jacon and jakoma refer to what is good and what is not good, respectively. In Quechua, the equivalents are allin and manam allin. However, these pairs do not express an absolute dualism between good and evil. Instead, they reflect a situated, contextual, and relational understanding of value. A similar dynamic applies to the distinction between onaya (sage or healer) and yobé (sorcerer), a pair whose differences are complex, fluid, and often subject to interpretation.

Drawing from my personal and familial experience – one also shaped by Christianity – I understand the onaya as someone who possesses spiritual weapons, used not out of hatred, but for protection and healing. The line between medicine and sorcery, therefore, is not fixed; it depends greatly on the perspective from which an action is interpreted.

This is a controversial and sensitive topic. I always clarify that my understanding comes from the knowledge passed down through my family. And since my Indigenous family is also Christian, it is difficult to fully disentangle Christian elements from the ancestral wisdom I have inherited and now reflect upon. While the foundation of my thinking is rooted in ancestral knowledge, its expression is heterogeneous and often intertwined with Christian motifs.

In Shipibo, onaya refers to the traditional healer, while yobé is commonly translated as “sorcerer.” Yet some argue that yobé is not necessarily negative but simply refers to someone who possesses and manages spiritual weapons. In the everyday discourse of my family, however, yobé usually carries a pejorative connotation. Interestingly, those who offer more neutral interpretations tend to be more assimilated into Spanish-speaking and mestizo cultural frameworks – at least from my perspective.

What is certain is that all onaya possess spiritual weapons. That much is indisputable. The real question is, where do we draw the line between legitimate defense and harmful sorcery? Two main distinctions can be made. First, the sorcerer tends to act compulsively, driven by antisocial impulses they either cannot or choose not to restrain. Their actions are motivated by the intent to harm. The onaya, in contrast, uses their abilities in response to harm already inflicted, whether upon themselves or their patients—and ideally, they do so without hatred.

Nonetheless, accusations of sorcery are fraught and often ambiguous. In my own family, individuals regarded by some as healers are seen by others as sorcerers. One recurring pattern I’ve noticed is that the person who initiates spiritual harm is often the first to accuse the other of being a yobé. This cycle of accusation and counter-accusation further obscures the boundaries.

Still, an ethical distinction remains possible, and I hold firmly to that conviction. Whether this distinction was more apparent in precolonial times is uncertain. I suspect it may have been, though I have no empirical evidence – only a strong intuition. Even today, people I recognize as healers are sometimes labeled sorcerers by others. Ultimately, this is a relational matter, shaped by one’s position and the nature of their relationship with the person in question. Accusations of sorcery often express deeper emotional or social tensions – envy, resentment, ruptures in kinship – which complicate the moral clarity of such judgments. Despite the conceptual distinction I advocate, in practice the boundaries between healer and sorcerer remain fluid, often evaluated less by intention than by perceived outcomes.

In my writing, I have made the conscious decision to uphold a conceptual distinction between onaya and yobé. I make no claim to neutrality; rather, I consider my perspective valuable precisely because it is situated – shaped by family lineage, lived experience, and spiritual inheritance.

Within the ritual setting, how does language operate from a technical or technological perspective in the healing process?

In healing rituals such as those involving ayahuasca, the chant is not merely expressive – it is performative. It acts as a poetic technology that inscribes vibrational designs, known as kené, upon the body. These are not static, geometric symmetries, but living, dynamic patterns. Through the chant, the body is cleansed, reordered, and realigned by the medicinal strength of the plants, a healing strength that is transmitted through sound.

Some contemporary healing chants even incorporate technological imagery – antennas, motors, tanks, airplanes – revealing that Indigenous knowledge is not frozen in an idealized past. Instead of portraying Indigenous knowledge as fixed or archaic, this show it as generative, adaptive, and capable of absorbing and transforming modern imaginaries.

Importantly, the chant is also scented. To interact with spiritual beings, the onaya must transform their bodily odor through strict dietary practices and the application of specific plants. Only when the healer’s body “smells” like a plant can they access other spiritual realms. The need to change one’s scent is fundamental, as the performative force of the chants arises from the healer’s relationship with suprasensible beings and worlds. The human voice gives body to the energetic flows that descend from these spiritual realms. This underscores the profound corporeal commitment required of the onaya: healing is not just a matter of knowledge but of bodily metamorphosis.

The chant is not a communicative tool in the conventional sense; it is a vibrational conduit through which the onaya channels the curative force of the plants. In doing so, the chant traces sonic kené upon the body, reconfiguring it through rhythmic, symmetrical sound patterns. And these designs, too, are scented: they are accompanied by a transformation in the healer’s bodily odor, which is crucial for attracting spiritual allies. In this sense, plant medicine requires an integrated transformation of the senses—auditory, olfactory, tactile, and beyond.

Some contemporary healing chants even incorporate technological imagery – antennas, motors, tanks, airplanes – revealing that Indigenous knowledge is not frozen in an idealized past. Instead of portraying Indigenous knowledge as fixed or archaic, this show it as generative, adaptive, and capable of absorbing and transforming modern imaginaries. It is dynamic and responsive, continuously reconfigured. Onaya have integrated modern imaginaries into their visions, including futuristic technologies not yet realized in our world. From this perspective, the spiritual owners of the plants (rao ibo) are sometimes envisioned as scientists more advanced than humans, appearing in dreams as beings operating laboratories or complex systems.

The role of scent is fascinating. Even in the development of virtual realities, incorporating olfactory elements is being explored to enhance immersion.

Exactly. In modern hierarchies of perception, smell is frequently marginalized. Among the Shipibo, there is an extraordinary capacity to distinguish between subtle variations in smell. For instance, the Shipibo have specific terms for distinct odors, including those associated with menstrual blood or armpit odor, for example. This heightened olfactory sensitivity is integral to the healing process: the perfumed chant both purifies and reweaves the body. There is a poetic expression that encapsulates this power – min yora abano, “I am making your body.” The chant does not function as a mechanistic form of communication; it enacts transformation. It does so from a kind of multisensory poetics in which healing is at once vibrational, aromatic, and aesthetic. All these ideas open space for a radically different ontology of language – one where words do not just signify, but quite literally shape reality.

How do you relate this to the idea of a different conception of technology? Could we speak of a situated techno-diversity?

It’s important to clarify what we mean by “technology.” My understanding is, in part, informed by Heidegger’s reflections on technē – not as mere instrumentality, but as a mode of revealing. From this perspective, technical language in its modern, utilitarian form is oriented toward efficiency, precision, and neutrality. It seeks to transmit information in the most direct and unambiguous way possible. Ritual language, on the other hand, is not concerned with transmitting data. It is poetic in nature, and its function is performative. It acts upon the world – it shapes, transforms, and reorders.

In this sense, the healing chant can be understood as a form of poetic technology. It is a precise and intentional use of sound, breath, and rhythm that activates a transformation in the body and spirit. Unlike modern machines, whose efficacy is judged by output and functionality, poetic technologies operate through resonance, alignment, and relationality. They do not impose control over the world but rather attune the body and the cosmos to a shared vibrational field.

Do you believe these practices could contribute to a rethinking of technology?

Absolutely. I often think of the Andean quipu – a system that enabled sophisticated astronomical and administrative calculations without severing the sacred bond with the cosmos. Temples were aligned with celestial cycles through external visual records, demonstrating that not all technologies entail a rupture with the sacred. What truly matters is the paradigm within which a technology is embedded. In the context of modernity, writing, printing, and algorithms have largely served logics of control, extraction, and standardization. But these tools could be deployed otherwise, within other cosmological frameworks.

The quipu stands as evidence that alternative, culturally grounded technological trajectories were – and still are – possible. Had such systems continued to evolve uninterrupted, we might today speak of an “Andean cybernetics” – a mode of information processing and world-organization grounded in relationality rather than domination. Based on my experience, I believe it is possible to imagine and even design technologies that do not isolate us from the living world but instead deepen our sense of connection with the totality of life.

Viewed through this lens, medicinal chants can be understood as a form of poetic technology – a term that challenges the dominant association of technology with mechanical or digital devices. It invites us to recognize that Indigenous knowledge systems generate technologies as well: not of metal or code, but of voice, breath, scent, and vision. These are not symbolic stand-ins for science but precise and rigorous practices of world-making. The onaya’s chant is not merely a cultural artifact; it is an embodied technique of transformation. It heals not by extraction or repair, but by restoring balance among human and nonhuman beings, and by attuning the body to the vital forces that sustain existence.

How are the youth and the broader Shipibo-Konibo community engaging with information and communication technologies (ICTs) today?

The relationship is remarkably organic. Young people—and the Shipibo-Konibo community more broadly – engage with information and communication technologies (ICTs) in a fluid, intuitive way. This coexistence is also reflected in symbolic and ritual expressions. I have written an article (currently unpublished) that explores how these technological motifs are integrated into ritual discourse and everyday healing practices. This is far from anecdotal: young people in the community are deeply familiar with platforms like Facebook and make widespread use of mobile phones. Digital life and ritual life are not seen as separate spheres – they intertwine, and this convergence finds expression even in the most sacred aspects of Shipibo healing.

Crucially, these are not superficial borrowings or symbolic decorations. In expanded states of consciousness, visionary experiences frequently depict spiritual technologies that are more advanced than human ones, associated with both benevolent and malevolent entities. Plants, for example, are often envisioned as scientists operating complex laboratories filled with computers and technical equipment – suggesting a vision of nature as a bearer of highly specialized, even futuristic, knowledge. Likewise, harmful beings – sometimes described in extraterrestrial terms—are imagined as wielding advanced technologies linked to illness or spiritual warfare.

Such representations offer a strong alternative cosmotechnical vision – one that redefines the very notion of technology. In many chants, the onaya (healer) is described as a kind of receiver, like a radio, capable of tuning into spiritual frequencies and adjusting channels with precision. One of our uncles, who is an onaya, told us the other day that his connections to the suprasensible worlds are like electrical cables. While I have yet to encounter a chant that explicitly references the “internet,” I believe such imagery could soon emerge, given the continual evolution and creativity of ritual language.

From this perspective, plant-based technology is not only imagined as functionally superior but also ethically wiser. While modern societies strive to build an “Internet of Things” to artificially link objects and systems, plants are already part of a living network – an ontological web where knowledge, perception, and ethics are inextricably bound. This vision challenges the prevailing technological paradigms of modernity and repositions the forest as a site of innovation.

Within this framework, my wife and I are working on projects that start from a simple but counterintuitive question: What if the most advanced technologies are not being built in Silicon Valley but are already singing in the forest?