The members of Girasolas | Courtesy of Kristina Konrad

Lorena Cervera is a documentarian, writer, teacher and holds a doctorate in Film Studies from University College London (2022). She has directed the short films “Pilas” (2019), “#PrecarityStory” (2020) and “Processing Images from Caracas” (2022). She has published various articles and chapters on documentary cinema, feminist cinema and Latin American film collectives.

Which films come to mind when thinking about the 1970s and 1980s? These decades saw the rise of the global blockbuster, stories led by patriarchal figures often fighting against the unknown and in which women were little more than a servient, orbital character. These films significantly shaped cultural imagination for generations and became the primary, if not the sole, focus of attention for film criticism and film scholarship. Far away from Hollywood, different understandings of cinema were also emerging. One of these cinemas grew out of another kind of global phenomenon and was led by women. Rather than being interested in commercial success, epic narratives, aesthetic excellence, or technical perfection, it was a cinema that sought to work collaboratively, raise consciousness, prompt public debate, and advocate for policy making.

Over these years, women around the world were gaining greater access to education and employment, were inspired by ideas of emancipation and equality, and formed movements that challenged traditional gender roles. One of the events that facilitated the rapid circulation of feminist ideas on a global scale was the UN World Conference on Women, held in Mexico City in 1975. This was the first of four conferences whose main objective was to tackle gender inequalities by involving women in decision-making.1 From institutional initiatives to grassroots organizations, women united to fight for their rights (Olcott 2017). Amidst this uprising, several feminist film collectives emerged, adding to this momentum by making films and videos that disrupted the representations of women on screen, challenged their seclusion from the public sphere, and both fuelled and documented feminist campaigns and events. Despite the magnitude and significance of feminist cinema, its influence remains largely unspoken. Recently, this marginalisation has begun to shift and, for instance, Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles was ranked first on the critics’ poll of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time in 2022, fifty years after its making.2

UN World Conference on Women, Mexico City, 1975 | UN Photo/B. Lane

Even though feminist film collectives were formed in different parts of the world during the 1970s and 1980s, in this article, I provide an overview of those that emerged in Latin America.3 The focus on this region is motivated by two primary reasons. First, in general terms, collective living, collaborative practices, and community solidarity are core values that articulate many societies from Patagonia to the Caribbean. Thus, collective filmmaking found its home amongst Latin American feminists. Second, as a cinema that operated at the margins, outside of Hollywood and Europe and within the then so-called Third World, Latin American films directed by women have faced a double exclusion because of the power imbalances caused by the North-South divide and gender inequalities. Today’s renewed interest in women’s cinema and the Global South has opened up the opportunity to revisit its history and reclaim its importance.

These collectives are the Mexican Cine Mujer (1975-1986), the Colombian Cine Mujer (1978-1999), the Venezuelan Grupo Feminista Miércoles (1979-1988), the Brazilian Lilith Video (1983-1987), the Argentinian Cine Testimonio Mujer (1983-1993), the Uruguayan Girasolas (1987-1993), and the Peruvian Warmi Cine y Video (1989-1998). Each of these collectives were preoccupied with inscribing women’s stories into film and articulating different ways of doing. By implementing collective and collaborative modes of authorship and production, they refused to attribute creative mastery to a single auteur and displaced the centrality of the director in the decision-making, subverting the hierarchies associated with film production. Some collectives chose not to credit individual directors; in others, its members rotated above- and below-the-line roles. They all made decisions based on consensus. In the making of their films, feminist filmmakers worked alongside activists, social organisations, and subaltern women to tell stories that had long been excluded from filmic representation. These collaborative processes fostered the development of affective relations that were ultimately reflected on screen through different formal strategies (Cervera 2022b).

A photograph taken by Ana Victoria Jiménez and included in Cosas de Mujeres (1975) of a protest for the decriminalisation of abortion held in Mexico City | Courtesy of Rosa Martha Fernández

The logo of the Colombian Cine Mujer | The Cine Mujer Foundation

Despite sharing the same name, the Cine Mujer groups did not learn about the existence of each other until 1981, when they met at the First Latin American and Caribbean Feminist Encuentro in Bogotá.4 The Mexican group was formed by film students of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM)–Rosa Martha Fernández, Beatriz Mira, and Odile Herrenschmidt, amongst others. They produced eight short films exploring some of the key feminist issues of the time, including on abortion, rape, domestic work, women’s gatherings, prostitution, and labour exploitation.5 The Colombian Cine Mujer was founded by Eulalia Carrizosa and Sara Bright, and later joined by Rita Escobar, Patricia Restrepo, Dora Cecilia Ramírez, Clara Riascos, and Fanny Tobón. From 1978 to 1999, this collective produced short films, documentaries, television series, and videos, and became a distributor of Latin American women’s cinema. Their films explored topics such as the unrecognised work of the housewife and the daily struggles of women living in slums or remote rural areas. They also made didactic films about health, sexual violence, and organising; and documented feminist events. As I have argued elsewhere, ‘its twenty years of activity make it one the world’s most enduring feminist film collectives’ (Cervera 2020: 150).6

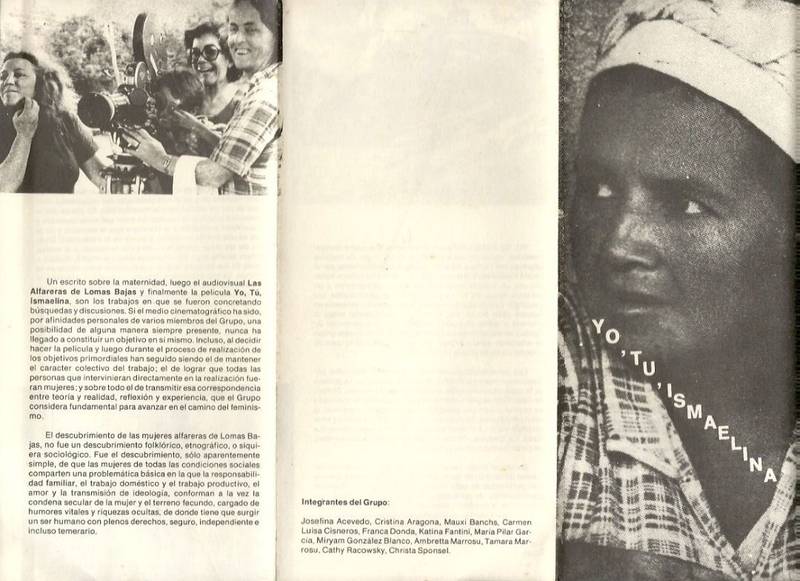

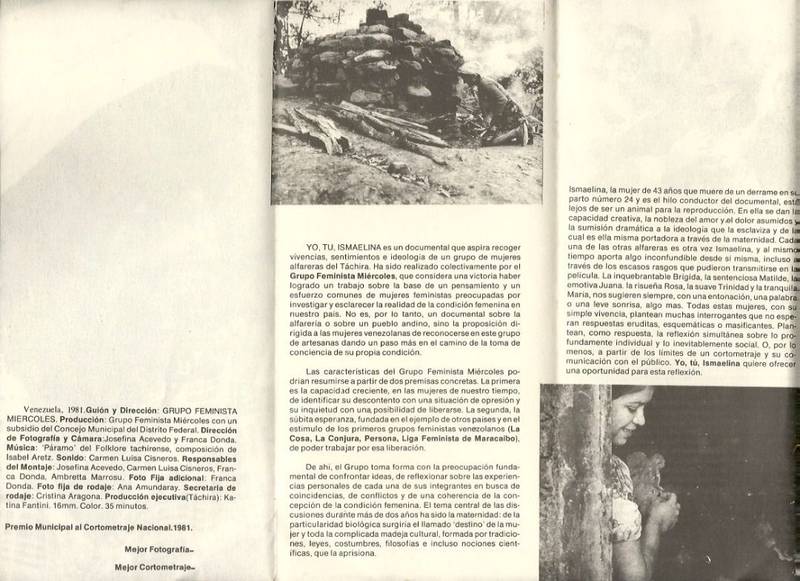

The Venezuelan Grupo Feminista Miércoles (1979-1988) and the Uruguayan Girasolas (1987-1993) were formed by an alliance between migrant European women and local women. For instance, many of Miércoles’ members were Italians who had immigrated to Caracas during the postwar. They produced the documentary Yo, tú, Ismaelina (1981) to raise awareness about maternal mortality and the videos Argelia Laya, por ejemplo (1987), Eumelia Hernández, calle arriba, calle abajo (1988), and Una del montón (1988). These productions responded to the urgency of creating an audiovisual archive of the feminist movement in Venezuela (Cervera 2022a). Girasolas’ driving force was Kristina Konrad, a Swiss camera operator who alongside Maria Barhum, Brenda Falcon, and Graciela Salsamendi made videos to illustrate the social changes that were happening in Uruguay in the aftermath of the dictatorship (1975-1985), including Manifestación negros (1988), Rompiendo el silencio (1988), and Yo era de un lugar que en realidad no existía (1988). Later, they focused on issues that specifically affected women, such as the lack of job opportunities, reproductive rights, motherhood, and the feminisation of poverty, in videos such as De la mar a la (1989), Por centésima vez (1990), and Comunamujer (1993) (Torres 2023).

[4a and 4b. Brochure of Yo, tú, Ismaelina (1981) | Grupo Feminista Miércoles]

The Brazilian Lilith Video (1983-1987) was a prolific collective founded by Jacira Melo, Márcia Meireles and Silvana Afram. Its main production was the television series Feminino Plural (1987), comprised of five episodes, as well as other videos addressing issues such as prostitution, women workers’ rights, women’s health, violence against women, and racism and black pride. Some of them are Os Direitos da Mulher Trabalhadora (1984), A Saúde da Mulher Trabalhadora (1984), Mulheres no Canavial (1986), and Beijo na Boca (1987) (Albuquerque 1988). Although lesser known, the Argentinian Cine Testimonio Mujer (1983–1993) was founded by Laura Búa and Silvia Chanvillard and produced three films: Lo estamos haciendo (1984), Solas o mal acompañadas (1988), and No sé porque te quiero tanto (1992), exploring themes related to motherhood, reproductive rights, and domestic violence. Like other collectives, its production sought to contribute to public debate surrounding legislative change –in this case, the 1987 law that legalized divorce (Campo 2022).

WARMI Cine y Video (1989-1998) was a Peruvian collective founded by María Barea, Amelia Torres, and María Luz Pérez Goicoechea. It was primarily concerned with instrumentalizing cinema to create consciousness-raising tools to empower subaltern women, such as those women and girls who lived in slums, worked in domestic service, or were involved in gangs. During its nearly ten years of existence, it produced the short-documentary Porque quería estudiar (1990), the feature-length film Antuca (1992), and the episode Hijas de la violencia [Daughters of War] (1998), amongst others (Seguí 2022). The renewed interest in Barea’s filmography is a clear example of how feminist scholarship can help the vast task of rescuing and resignifying cinemas that, despite their importance, were overshadowed.

Frame from Antuca (1992) | Courtesy of María Barea

However, in general terms, little information has circulated on these collectives and their filmographies. Much of the documentation that details their history and production remains uncatalogued, has never been published, or is stored in private homes, rather than in official archives. And most of what has been published is dispersed across small publications, rather than being compiled in the books and journals that document what is generally accepted as history. After years of neglect, many of these small publications have disappeared, while others remain scattered in different countries, often kept under inadequate conditions. Furthermore, many feminist films have not been properly stored and are rapidly perishing. This is the case of Yo, tú, Ismaelina and, more generally, the filmography of Grupo Feminista Miércoles. The absence of women’s films and other related materials from canons, archives, and historiographies has had profound effects not only on how knowledge is produced, but also on how collective identities are constructed and remembered. This article joins other efforts in recovering and restoring the value of feminist cinema, focusing on the work produced by feminist film collectives across Latin America during the 1970s and 1980s, and by doing so, intends to encourage more scholars, archivists, and curators to take further steps towards the study, preservation, and dissemination of this vital work.