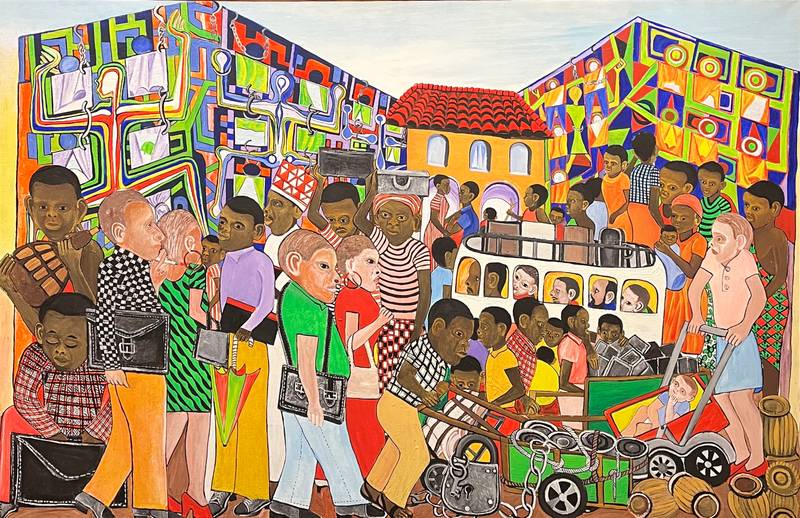

Installation view showing Mmapula Mmakgabo Helen Sebidi, Who are We and Where are We Goin?, 2004-2008, oil on canvas. Photo: Jean-Baptiste Béranger

Mmabatho Thobejane (she/they) is a sangoma and cultural practitioner working across curating, craft and text as material practices. Mmabatho’s curatorial practice encompasses pono ya moya, an African Traditional Health practice focused on ancestral healing, through which, guided by their ancestors, they curate and facilitate workshops like altar sessions. Mmabatho’s practices take up the triad relationship between ourselves, each other and the earth.

When We See Us: A Century of Black Figuration in Painting, originally conceived and organised by Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (Zeitz MOCAA), currently on view at Liljevalchs until August 2026, underlines just how far into the age of “the end of the innocent notion of the essential black subject” we are.1 The exhibition acknowledges that Black subjectivity is not fixed but continually shaped by history, politics and culture. It offers beauty and serenity while also revealing the complexities and limitations inherent in “representing” Black life. It makes bare the complex contexts within which Black artists are creating today. By taking our time to look closely, we can engage with what these artists are theorising and proposing in their content and form. Since its opening at Zeitz MOCAA (2023), When We See Us has travelled to Kunstmuseum Basel (2024) and Bozar, Brussels (2025), and now arrives at Liljevalchs in Stockholm. This international migration underscores the resonance, relevance, and urgency of Black figuration for the global art industry, including art institutions and the market. What meanings abound with its arrival in northern Europe? And, if Black subjectivity resists fixity, how does When We See Us attempt to hold, organise, or even choreograph this multiplicity across its themes?

When We See Us is organised around six themes: The Everyday, Joy and Revelry, Repose, Sensuality, Spirituality, and Triumph and Emancipation. While the unofficial starting point of the exhibition is The Everyday, the most intuitive entry point is Spirituality, which sits on the bottom-most floor adjacent to the cloakroom and lockers. Spirituality contains works in which the human body collapses, disintegrates and collaborates with its environment. One of the first works seen here is Sthembiso Sibisi’s Baptism: Spiritual Healing in the Sea (2005). At the forefront of the oil on canvas painting scene is a pastor, dressed in yellow and green, baptising a churchgoer in green and white. In the background, another churchgoer is being baptised by a peer, both dressed alike. The sea around them is wavy and turbulent, perhaps made so by the group’s movements or Moya. To the left, a surfer stands in calmer waters and watches the scene unfold. In the distance to the right is what looks like an oil tanker. This scene is both humorous and serious to me. Perhaps it is mme wa kereke on the far right, whose coming up for air or being enraptured by Moya, looks like resistance and struggle. And how all this is being witnessed by an unsuspecting surfer, perplexed and intrigued. The surfer has an air of unknowing and innocence, while the small congregation is engaged in serious spiritual business. There is, in this meeting and juxtaposition, a difference in gazes and thus in experiences.

Sthembiso Sibisi, Baptism: Spiritual Healing in the Sea. 2005, oil on canvas. Photo: Friyal Mohammedsadik, courtesy of Liljevalchs

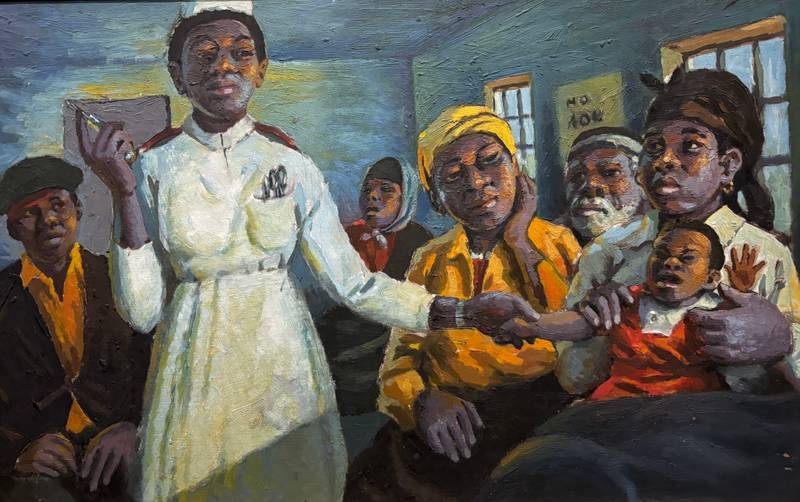

George Pemba, At the clinic, 1979, oil on canvas. Photo: Friyal Mohammedsadik, courtesy of Liljevalchs

Sthembiso Sibisi (1976-2006), trained as a mechanical engineer before applying his draughtsman’s skills to a career in art. Sibisi worked across painting and printmaking to depict everyday scenes and was inspired by the painter and writer George Pemba (1912-2001), known for his social realism, which portrayed the daily lives of Black South Africans under apartheid, capturing the community’s joy and resilience along with its hardships through a blend of realism, impressionism, and expressionism. Sibisi’s work in the exhibition is part of a series (across media) that depicts and reprises indigenous African spiritualities through gatherings inherent in African-initiated churches such as the ZCC and the Nazareth Baptist Church, as well as those within the ubungoma tradition.

The scene Sibisi paints in Baptism: Spiritual Healing in the Sea reveals an epistemic and, perhaps, ontological difference in how Black and White communities relate to the sea presently and historically. In his work, the sea emerges as a central site and collaborator, while the ship evokes intertwined histories of colonialism and racial capitalism – histories of Black subjugation. Sibisi collapses time and worlds with differing arrangements of knowledge. This exploration of collapse continues later in the section with works such as Edouard Duval-Carrié’s plexiglass mural The True Story of the Water Spirits (2004) where, by looking past the ornate lattice of leaves and spirit-bearing flowers, we discern small embedded vignettes – archival images of lynching and torture – which highlights that Black spirituality is always in conversation with and respondent to Black suffering.

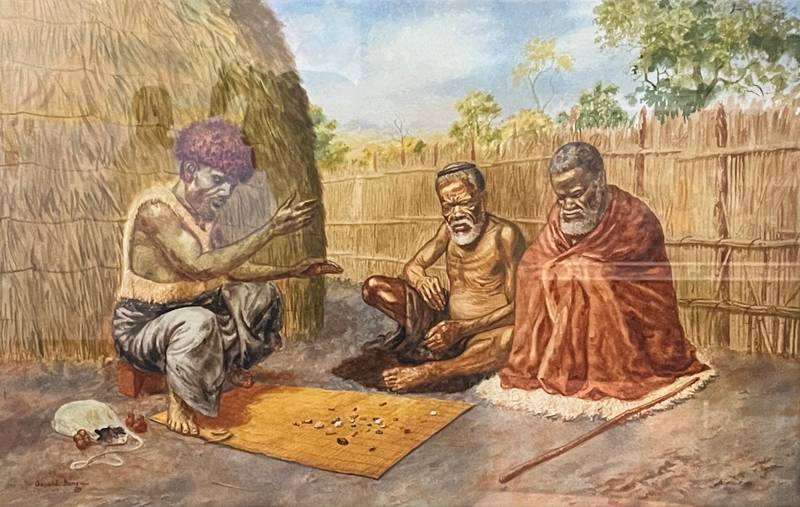

Other notable works within this section are an oil on board painting titled O Curandeiro (The Sangoma or the Healer) (1964) by Malangatana Ngwenya, and Gerard Bhengu’s watercolour, Consulting the Isangoma (u.d). Installed next to each other, they pique my interest in how they depict the same scene of ‘consulting a sangoma’ through distinct painting styles, and how their respective colour schemes highlight and omit varying aspects of the scene, perhaps proposing differing concerns, preoccupations, and intentions.

Gerard Bhengu, Consulting the iSangoma. n.d. watercolour on paper. Photo: Mmabatho Thobejane

Malangatana Ngwenya, O Curandeiro (The Sangoma or the Healer), 1964, oil on board. Photo: Friyal Mohammedsadik, courtesy of Liljevalchs

This observation about the contrast and dialogue between the two paintings recalls Sean O’Toole and Simphiwe Ndzube’s response to a question by When We See Us co-curator Tandazani Dhlakama, during a conversation held as part of Congress: The Social Body in Three Figurative Painters – an exhibition curated by O’Toole and presented at the Norval Foundation from October 2021 to January 2022. Dhlakama asked O’Toole and Ndzube whether the recent spotlight on figurative painting might be connected to social politics. O’Toole emphasized that the works featured in The Social Body in Three Figurative Painters – including Sibisi’s Baptism: Spiritual Healing in the Sea (2005) and George Pemba’s At the Clinic (1979) and Xhosa Beer Drinker (1973), also shown in When We See Us – are not simply documentary records of a moment in time, but rather “interpretations and translations and in interpretation and translation things are lost and gained.”2 As part of his response, he highlights that for George Pemba, the greatest discovery was not the figure but “colour and what colour can do.”3

The invocation and repetition of the we, our, us conjure, cast and hail a collective that is unified even as all its differences are named. Of course, one meets this first in the exhibition’s title.

In Naudline Pierre’s oil on canvas painting, Close Quarters (2018), a red figure communes in the dark with an angel and/or other spirits. In Devan Shimoyana’s The Abduction of Ganymede (2018), made on canvas using oil, coloured pencil, dye, sequins, collage, glitter, and jewellery, a bejewelled figure with a shimmering afro is flying and entangled with an eagle in a kaleidoscopic setting. Jacob Lawrence’s series of silkscreen prints from 1989-1990, created for a special edition of the Book of Genesis published by the Limited Editions Club, Genesis Creation (1989), proposes a porous relationship between the church and the landscape. In this section, there is a reaching for a beyond that casts the human figure as a vehicle. The body emerges as porous and in an intimate exchange with worlds seen and unseen. At their root and through their insistence on the relationship between the body, land, spirit, and being, Black spiritual beliefs and practices offer other ways to animate being and thus to ‘look’. Beginning my arrival in Spirituality then feels like a sort of tuning fork, attuning my gaze and concerns to these other sensibilities. From here, I set off to look further.

Devan Shimoyama, THE ABDUCTION OF GANYMEDE, 2019, oil, colour pencil, dye, sequins, collage, glitter, and jewellery on canvas. Photo: Friyal Mohammedsadik, courtesy of Liljevalchs

Uses of Language and the Troubled We

It is after Kambui Olujimi’s artwork All I Got to Give (2019) that I encounter the wall text introducing the Spirituality section, which begins with “Our spirituality cannot be separated from everyday life”. It continues, “We embrace the waves during a Baptism: Spiritual Healing in the Sea with Sthembiso Sibisi, or we gain revelation with Edouard Duval-Carrié’s The True Story of The Water Spirits. This is our metaphysical world – our utopia.” Each themed section of the exhibition opens with a similar language of invitation. At the entrance to The Everyday one reads: “There is beauty in our everyday lives… [o]ur domestic spaces emit aromas of chapati, thiéboudienne, guru, collard greens or plantain.” Moving into Sensuality the text declares: “Here we make love and love each other unapologetically… [We] can be as delicate as Elladj Lincy Deloumeaux’s À mes yeux…”. Before Triumph and Emancipation, we are greeted with: “here we are strength personified… we are reminded that we come from a continent of kings and queens. After all, we built the pyramids”. Entering Repose: “In our resplendent outfits, away from obligations, we take leisurely strolls, travel and traverse new emotional and physical horizons.” Finally, within Joy and Revelry, we read “… we know how to have a good time; see how we kwasa kwasa, jaiva and step to the musical beats of… you can feel our soul in Romare Bearden’s Jazz Rhapsody, you can feel our rhythm in Chéri Samba’s Live dans les sous-sols du Rex.”

The curators express a desire to turn away from struggle and suffering, the contexts in which Blackness is often stereotypically represented, by foregrounding ‘Black joy’ and ‘self-representation’. The result is a tone that, in its optimism, overly guides the viewers’ gaze, leaving little room for interpretation. In this process, the works are reduced to illustrations of ‘black joy’ and the curatorial framing.

The tone and style of the wall texts do two things. First, the invocation and repetition of the we, our, us conjure, cast and hail a collective that is unified even as all its differences are named. Of course, one meets this first in the exhibition’s title, When We See Us. Secondly, the tone and style of the wall texts risk overdirecting the viewers’ gaze, and, in so doing, relate to the artworks as illustrations of the curatorial framing, foregrounding “joy and self-representation”. This overdirection risks flattening the works and burying their artistic intention and the myriad meanings they produce and imbue. It risks diminishing complex readings in favour of conditioning the audience toward noticing joy and self-representation. I begin by attending to the proliferation of the we, us, and our.

Installation view showing Mmapula Mmakgabo Helen Sebidi, Who are We and Where are We Goin?, 2004-2008, oil on canvas. Photo: Jean-Baptiste Béranger

In the exhibition catalogue, co-curator Dhlakama writes that, “[t]here are numerous Black identities that emerge in diverse contexts where differences manifest themselves – historically, geographically, culturally and politically, to name a few”.4 This is reminiscent of Stuart Hall writing, “if the black subject and the black experience are not stabilised by Nature or by some other essential guarantee, then it must be the case that they are constructed historically, culturally, politically.”5 At face value, there is little difference in what Hall and Dhlakama are saying, but upon a closer reading, distinctions in their respective views of what constitutes the black subject emerge. For Hall, history, culture and politics construct the black subject. There is no black subject before and without these. For Dhlakama, the black subject is always in existence “stabilised by Nature or by some other essential guarantee”6 – blackness lies first and foremost in the body – and history, culture, politics, and geography are external accretions that create difference therein. This view recurs throughout When We See Us. Why is it possible to hail and speak about an undifferentiated and unified Black “we” even as the exhibition attempts to “celebrate multiple temporalities, contradictions and contestations of Blackness.”7? To make exhibitions about Blackness, especially Black figuration, one has to ‘accept’ the parts of race that are ‘stable’ and hopefully move beyond them to engage what the works are proposing as sites of critical and embodied thinking and theorising.8 Recent publications such Dear Science and Other Stories by Katherine McKittrick, A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See by Tina Campt, Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Antiblack World by Zakiyyah Iman Jackson and Anteasthetics: Black Aesthetics and the Critique of Form by Rizvana Bradley excavate Black creative practices for their theorising and knowledge-making capacities, revealing how they challenge and find ways out of liberal humanist ways of being to move beyond “Man”.9 These theorists approach work by black and anticolonial artists for how it challenges the ‘human’ instead of being purely illustrative of liberal humanist notions of ‘representation.’

For When We See Us, the curators express a desire to turn away from struggle and suffering, the contexts in which Blackness is often stereotypically represented, by foregrounding ‘Black joy’ and ‘self-representation’. The result is a tone that, in its optimism, overly guides the viewers’ gaze, leaving little room for interpretation. In this process, the works are reduced to illustrations of ‘black joy’ and the curatorial framing. For example, Romare Bearden’s Jazz Rhapsody is illustrative of ‘our’ soul; ‘our’ rhythm can be felt in Chéri Samba’s Live dans les sous-sols du Rex and Elladj Lincy Deloumeaux’s À mes yeux is illustrative of black delicacy. For Black joy to emerge, the works are described and explained in foreclosed, flat ways. Who might this kind of framing be for?

On a recent visit to the exhibition, I turned around after taking in Mmapula Mmakgabo Helen Sebidi’s monumental polyptych Who Are We and Where Are We Goin? (2004-2008), to find a large group of white museumgoers and their guide, at the end of their introductory walk, standing behind me. It dawned on me that these wall texts could be read, in part, as translations for a largely white audience. This translation-like language flattens the artworks and overlooks the distinct theorising and meanings they produce. Subsumed under the curatorial voice is an implicit deprioritisation of the complexity and multiplicity therein. One notes that it is only in front of a white audience or for a liberal humanist agenda that Blackness and Black people must emerge as “coming from a continent of kings and queens”.10 Is this translation-like language a failure of the exhibition or an inevitable feature of exhibiting Black art in predominantly white institutions?

Inherent in this translation, paralleled and perhaps spurred on by the focus on ‘Black joy’, is the desire to inscribe Blackness within the frames of liberal humanism. In an interview, Dhlakama says of the exhibition: “Why Black joy is so powerful and why maybe some people can call it a weapon is that it refuses the flattened, reduced, limited reading of Blackness because Black people sit outside and read just like other people and Black artists have been expressing themselves in nuanced ways: reclining, sitting, doing whatever just as every other artist have.”11

In African Modes of Self-Writing, from which When We See Us borrows the notion of ‘self-styling’, Achille Mbembe writes:

… denial of humanity (or attribution of inferiority) has forced African responses into contradictory positions that are, however, often concurrently espoused. There is a universalistic position: “We are human beings like any others.” And there is a particularistic position: “We have a glorious past that testifies to our humanity.”12

In foregrounding Black joy, in When We See Us, we witness a curatorial framing that navigates both universalistic and particularistic positions, as per Mbembe. This posits that the gaze is not entirely inward but responds to epistemic configurations that historically cast Blackness as inferior. Consequently, When We See Us emerges as belonging “to the discourse of rehabilitation and functions as a mode of self-validation” that “does not challenge the fiction of race”13. In this context, one can argue that the exhibition contributes to what Zakkiyah Iman Jackson calls ‘plasticity’, whereby

black(ened) people are not so much as dehumanized as nonhumans or cast as liminal humans nor are black(ened) people framed as animal-like or machine-like but are cast as sub, supra, and human simultaneously and in a manner that puts being in peril because the operations of simultaneously being everything and nothing for an order—human, animal, machine, for instance – constructs black(ened) humanity as the privation and exorbitance of form.14

For Jackson and Wynter, blackness is the site through which ‘the human’ coheres itself.15 This suggests that the lamented failures of liberal humanism – such as the dehumanisation of Black people through synonymising Blackness with struggle and pain – are not failures but central features of liberal humanist notions of being. Furthermore, Jackson argues that plasticity is the mode through which Blackness is produced as sub–, super–, and human all at once. It functions as a “mode of transmogrification whereby the fleshy being of blackness is experimented with as if it were infinitely malleable lexical and biological matter…”16 This dynamic is most demonstrated in the trajectory of Black people within the ‘exhibitionary complex’, including the white cube and museal frame, which have been globally exported.17 For example, on Djurgården, the island where Liljevalchs is located, the ‘Kolonialutställningen’ (The Colonial Exhibition), also known as ‘Senegalutställningen’ (The Senegal Exhibition), was staged as recently as 1931. It was an ethnographic exhibition where the Serer people of what is present-day Senegal were exhibited in what has been understood as a ‘human zoo’.18 Today, also at Liljevalchs and on Djurgården, blackness is on display as part of an exhibition on Black figurative painting, black joy and self-representation. Of course, When We See Us is far from being a human zoo. However, what I am trying to underline, as spurred on by Jackson, is that in both cases Blackness is the vehicle through which the liberal humanism of the respective time establishes, expresses and updates itself through the use of exhibitionary devices. We have seen how the liberal humanist framework has rearranged itself in response to uprisings and movements against antiblackness, such as #BlackLivesMatter and student movements like #RhodesMustFall. The widespread response has been one of inscribing Blackness into the grammars of Man, whereby Black people can be human ‘mimetically’ and as ‘homo oeconomicus’.19 We are also witnessing liberal humanism doubling down in the face of pro-palestine sentiments and movements.

In recent times, it is increasingly clear that liberal humanism is deeply flawed and, at its core, is genocidal. What does it mean to use the exhibition format as an attempt to inscribe Blackness into humanism’s frames and legibility at a time of concurrent genocides?

When We See Us opens with BNP Paribas named and listed as Liljevalchs’ ‘Main Partner’. In 2024, BNP Paribas, a French bank operating globally, launched its Nordic Foundation ‘to support culture, solidarity and the environment.”20 The bank, which has sponsored Liljevalchs since 2021, was found to be complicit in the genocide committed by the Sudanese government under Omar al-Bashir in Sudan by providing banking services.21 The bank is also alleged to be complicit in the genocide in Gaza and was named by Francesca Albanese in her report From economy of occupation to economy of genocide as one of the companies that are profiting off the genocide.22 The bank’s engagement in ‘culture, solidarity and the environment’, while being complicit in crimes against humanity, has earned the bank accusations of engaging in artwashing.23 Liljevalchs has since ended its partnership with BNP Paribas as the konsthall felt that questions received around the partnership were distracting from its mission.24 In some ways, When We See Us at Liljevalchs feels dated for its reprisal of liberal humanistic values and its focus on Black recognition and representation at a time when those values, their causes and effects, are as bare as they have ever been. ‘Elite capture’25 through the institutionalisation of Black recognition and representation has revealed deep betrayals that have cemented the death of the ‘innocent essential black subject’ and yet we find in 2025 a curatorial framing attempting to reprise this figure.26 However, even if the curatorial framing is pegged to a liberal humanistic lens, this is not necessarily synonymous with the narratives and meanings inherent in most of the artworks in the exhibition.

A Quiet Meandering

When We See Us is an exhibition that was created in response to the recent proliferation of Black figurative painting. The curators of When We See Us, aware of this proliferation, propose with their incisive and incredibly well-researched contribution to this dialogue that Black figurative painting has a more extended history than has been recently acknowledged, particularly by the market.27 To explore Black figuration through the grammar of a glossy ‘Black joy’ and to exclude pain and suffering certainly engages with Blackness as sellable and surfaces the art market as an additional target audience. Theorists Francesca Sobande and Emma-Lee Amponsah, in pursuit of holding onto Black joy’s radical potential, posit that it is necessary to distinguish ‘Black joy’ from ‘Black Joy™’.28 The latter signals the invocation of Black joy “in ways that are intended to be eligible to the competition and, often, commerce-oriented marketplace”, denoting “the commodification of Black emotions”29.

Having shrugged off the wall texts and now walking through the exhibition with a less glossy view of ‘Black joy’, one can earnestly make room for the other emotions that the works bring to the fore. Meleko Mokgosi’s mural-sized Pax Kaffraria: Graase-Mans (2014), immerses one in a familiar scene of Black labour: having work, not having work and the gendered nature of work itself. The quiet and everyday violence below the surface of this painting is the uninterrupted social organisation of Apartheid, even post-Apartheid. It is fascinating how Mokgosi simultaneously highlights and disappears place/context, which is always highlighted or disappears in relation to people, labour and property. The use of figuration here highlights not only self-representation but also the construction of the people-labour-property relation. It is not to be taken as fact or as stable. It has had to be drawn out from the abyss. I can take in the layers of Pax Kaffraria: Graase-Mans (2014) while reclining on Wolff Architects’ exhibition design, and with some quiet, can name the painting’s invocation of melancholy and a sense of pasts and futures foreclosed. In this quiet, I begin to sense a different kind of joy - one grounded not in spectacle but in interiority, labour, and persistence. Perhaps this is a feeling of grief?

Ancent Sol f., Nairobi City Centre, ca. 1985, oil on canvas. Photo: Mmabatho Thobejane

![Kangudia f. okänt, *Untitled \[im Autobus\]*, 1987, oil on canvas mounted on plywood. Photo: Mmabatho Thobejane](/images/cmj748i499nqo07thgqb6jmwv-800w.jpeg)

![Kangudia f. okänt, *Untitled \[im Autobus\]*, 1987, oil on canvas mounted on plywood. Photo: Mmabatho Thobejane](/images/cmj748i499nqo07thgqb6jmwv-lqip.webp)

Kangudia f. okänt, Untitled [im Autobus], 1987, oil on canvas mounted on plywood. Photo: Mmabatho Thobejane

Cinthia Sifa Mulanga, Wait your turn – Competitive Sisterhood, 2021, mixed media on canvas. Photo: Mmabatho Thobejane

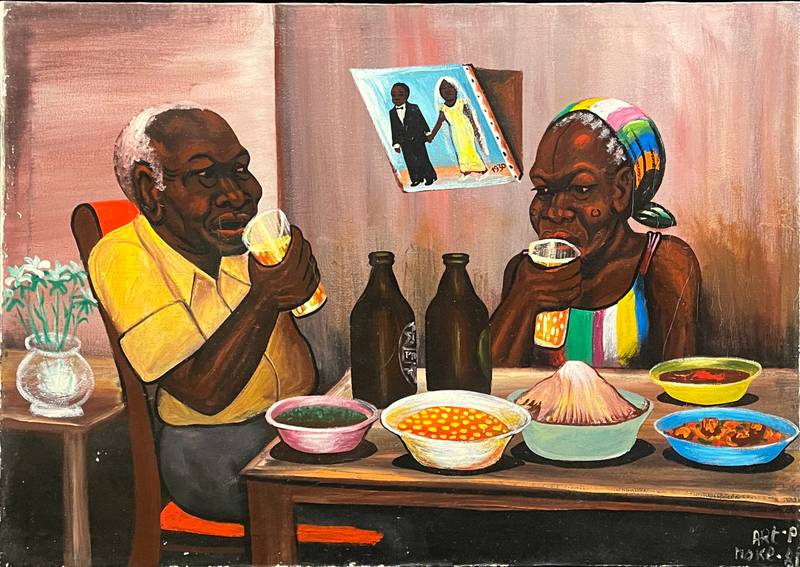

Moké f., Couple à table, 1981, paint on flour bag. Photo: Mmabatho Thobejane

Throughout the exhibition, we are drenched in quotidian scenes of black life. The chaotic commute is captured in Ancent Soi’s Nairobi City Centre (1985) and Kangudia’s Untitled [im Autobus] (1987), the latter of which takes on a more comedic quality. In both, packed public spaces evoke feelings of claustrophobia, spaciousness, and the going-on-ness of life. Intimacy between the two is depicted in Luis Meque’s Untitled (1992), Moké’s Couple à table (1981), Michalene Thomas’s Never Change Lovers in the Middle of the Night (2006) and Tiffany Alfonseca Espero que ya le dijiste a tu madre de nosotras (2020). The differing styles texture this intimacy in different ways. Meque’s Untitled (1992), leans towards abstraction and gives a sense of fleetingness or of a conversation one is not privy to, especially with the pair’s backs to the viewer. At the same time, Moké’s Couple à table (1981), created on a flour bag canvas, is more stable. One can make out the specificities of the who and the why, and, for a moment, is invited into the intimacy of a couple sharing a meal, an act they may have done over years of companionship. Gathering around a centre is present in works like Monsengo Shula’s Choix de troisieme sexe (2010), Cinthia Sifa Mulanga’s Wait Your Turn – Competitive Sisterhood (2021), Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi’s Ceremony (2020) and Gerard Sekoto’s The Evening Prayer (1942). The paintings’ respective compositions and artistic concerns together frame the centre as simultaneously stable and unstable ground continually made and remade by fluctuations in difference (or sameness) and inclusion (or exclusion). As Divine Fuh says, ‘the we is quite problematic’.30 Nomusa Makhubu furthers this by noting that invoking a Black ‘we’ is challenging to do without acknowledging the deep betrayals that are constitutive of it, betrayals such as xenophobic violence against African migrants in South Africa and the necessitated flattening of Black women and queer subjectivities that encompass this ‘we’.31

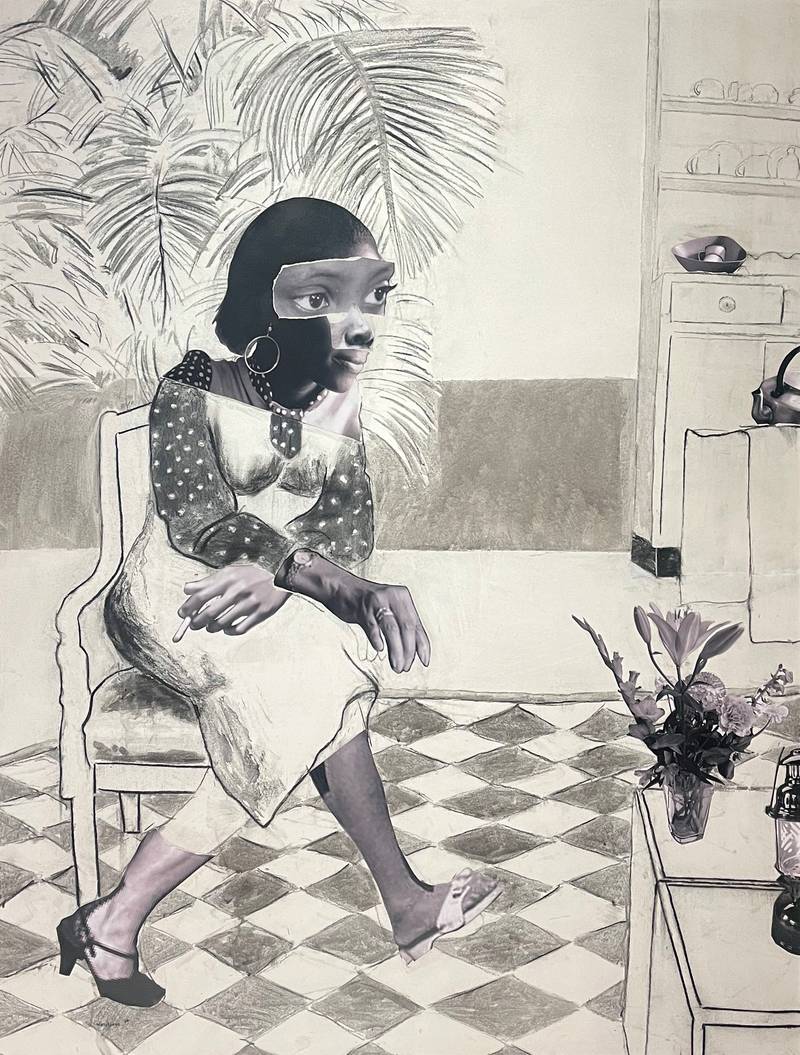

Many of the artworks display what Kevin Quashie calls ‘Quiet expressiveness’. For Quashie, quiet is a turn towards the interior and with an understanding of the interior as a political space that “is a simple part of what it means to be alive.”32 It feels to me as though works such as Olusegun’s Adejimo’s Ovie’s Repose (2012), Dominic Chambers’ All This Life In Us (2020), Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s 11 pm Friday (2010), Yoyo Lander’s I Can’t Keep Making the Same Mistakes (2021), Neo Matloga’s Mmadira (2020), and so much more, are tracing the quiet, revealing “desires, ambitions, hungers, vulnerabilities, fears” and emotional registers that encompass and exceed joy.

Neo Matloga, Mmadira, 2020, collage, charcoal, charcoal liquid and ink on canvas. Photo: Mmabatho Thobejane

To insist on representing and framing Black figuration within liberal humanism is a choice that narrows when it is represented within its institutions. Attention to Black creative and artistic practices that employ figuration in their expression reveals and depicts the complex workings of liberal humanism and the entangled positionings therein. Such close readings, coupled with the rejection of representation as the primary form through which Black humanity is recovered, complicate joy and underline that deep pain, grief, and difference are not in opposition but are co-constitutive of it. In this view, we find that it is not only joy that gains complication, but being at large. Rehabilitation aside, we may be reminded that the subjugation of Black people is not only the story of Black people but of humanity at large, which implicates whiteness and modernity. One deduces that inherent in reprising ‘the essential black subject’ is also the solidification of the innocent white subject, who could at one point look on at ‘human zoos’ and watch a lynching while picnicking, and who, today, can take in the proclaimed splendour of Blackness through an exhibition. The struggle and violence that When We See Us attempts to circumvent is not self-inflicted. The exhibition as a format presents liberal humanism’s trajectory, highlighting how it is, at its foundation, a vehicle for a particular genre of being. To highlight joy through liberal humanist grammars contributes to this trajectory. In times of concurrent genocides, in an effort to interrupt liberal humanism, it would be more honest to acknowledge and take a critical position against it.