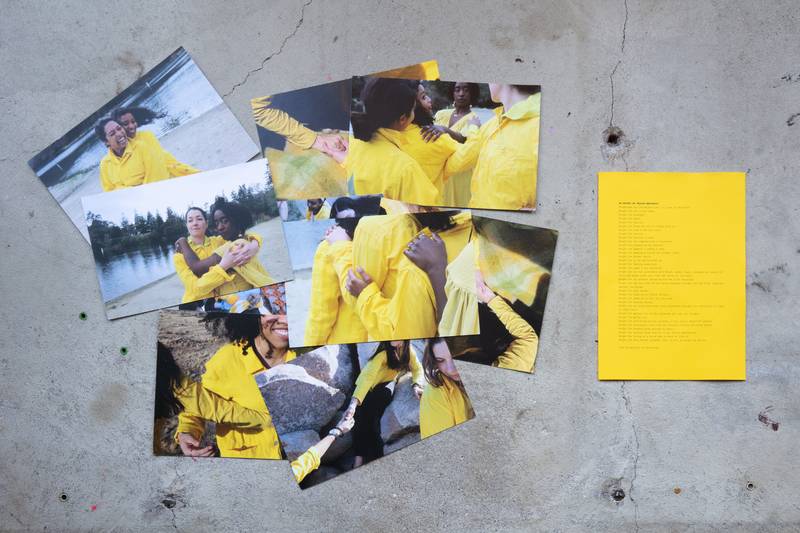

Amol K Patil, The Politics of Skin and Movement, Site specific installation, Kochi-Muziris Biennale, 2022. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Mansi Kashatria is a researcher-writer based between Sweden and India. With a postgraduate degree in Ethnic and Migration Studies and soon completing her PhD. in Culture Studies, she is tracing how the histories and imaginations of select-few contemporary art institutions are shaping their practices.

The recent ‘global turn’1 and ‘historiographic turn’2 in contemporary art discourse both rest on the claims that the contemporary is our shared now and that the global is our shared common. Claiming a contemporaneity3 brings a relevance and addition to the platform of the global where values, histories, and claims over the future are shared equally, as if on the same horizontal plane. But the ways in which artistic and curatorial as well as institutional practices respond to and negotiate with such claims are countless. And the existence of that multitude is a sign in itself of how the contemporary and the global are actually shared in hierarchical relationships, not equally.

These assumptions emerge from glossed-over fundamental structures that guide and make the hegemonic frames of references in the world. The reality is that the local-global binary persists, global south-global north binaries exist, and the dichotomy of individual versus collective still informs socio-political imaginaries that are primarily based on hierarchies and exclusions.

Once in a while, a slight recognition of these assumptions triggers responses such as more representation, better inclusion, a dive into antiquity or historicity to dig out better imaginaries to build futures, or of simply situating the ‘global south’ as a site of futurity. These attempts can be seen as ‘fixing’ the structural and experienced hierarchies of our world, and they probably do so—temporarily. There is nothing to say that any of these actions or responses are wrong or not necessary. But the pitfalls of such triggered responses are equally aplenty.

The practices of digging into the past to imagine more cosmopolitan or global futures often bypass a key question: Whose pasts are being invoked, and how is the contemporary actually being shared? In such reimaginations, the global south and its people are not just spatially homogenised but more strikingly, temporally displaced—imagined either as a reservoir, as tradition, or as some speculative, emancipated site of futurity that could save the world from the ills of capitalism. They are never truly here and now. And when it comes to representation practices, these have put a bracketing or lock on the identities of people who can then only perform within and through that identity, at the risk of otherwise being unheard or unseen. On the other hand, although sometimes contemporary art institutions can reveal what is being kept hidden or is being erased, sometimes they become spaces that neutralise the threat that anti-caste and anti-race works pose. However, the fundamentals of such kinds of reimaginations or of building alternative realities are mainly rooted in euromodern bias and a glaring assumption of western historical references as a universal overcast, leaving us with much unexplored and unchallenged. All leading to a condition of being spatially and temporally locked.

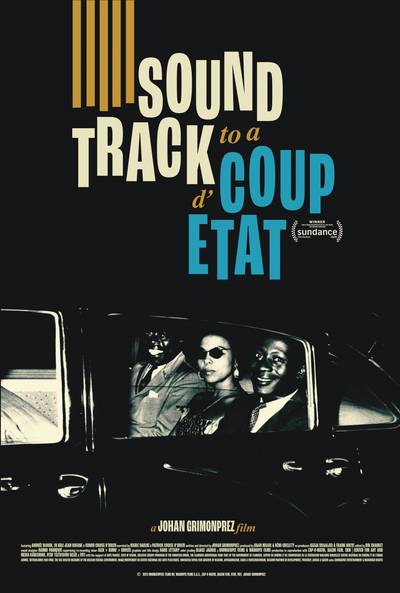

Allow me to illustrate these circumstances by drawing on two richly contextualised case studies: one biennale, ‘Kochi-Muziris Biennale’, Kerala, from the so-called global south, and one small-scale institution, ‘Konsthall C,’ Hökarängen, from the assumed periphery of the global north. I follow firstly, and perhaps more broadly too, the foundational narratives and practices of these two institutes in the context of the socio-political relationships in which they are geographically situated. Secondly, the inquiries then narrow down on select-specific artworks exhibited as part of their curatorial programs during the time period 2022-2024. In the case of Kochi-Muziris Biennale, I study their fifth edition called ‘In your veins flow ink and fire’ and therein Amol K. Patil’s artwork ‘The Politics of Skin and Movement.’ And for Konsthall C, I look at Ulrika Flink’s curatorial program from her time as the artistic director of the institute between 2021-2024.

Naturally, putting these two case studies side-by-side also opens up the analysis to the same mistake that divides the world and its people in binaries. That is of building comparison of practices situated in the global north versus the global south. So, to actively refuse such a comparative analysis, I move fluidly between deep, situated analysis and broader, relational critique. In other words, I use a retrospective form of writing, prioritise storytelling and regard what happens on the ‘field’ as the basis from which to arrive at a theoretical analysis afterwards. The engagement with people, institutions, and structures in both places therefore happens in a manner of ‘speaking nearby,’ taking from Trinh T. Minh-Ha’s works, to help in recognising that rigid boundaries and definitions of disciplines, borders, caste, race, and gender are interpersonal and ever-present.

Let’s now explore them one by one in some detail:

The Kochi-Muziris Biennale began with its first edition in 2012 in Fort Kochi in the southern state of Kerala, India. Since then, it has had five editions, and in December 2026, it will inaugurate its next edition. The Kochi-Muziris Biennale has given itself a hyphenated identity to claim, on the one hand, cosmopolitanisms from a mythological city called Muziris that existed 2,500 years ago and was characteristic of its maritime trade attracting Arab, Chinese, and Portuguese merchants over centuries. On the other hand, it lays claim to the multi-ethnic, religious, and communal identity of present-day Kochi, which has been the result of its colonial mercantilism and settler colonialist history. Even though Muziris’s official or formal existence remains contested, it has been used by the Keralan government to authenticate all the historical sites’ narratives and prep them for a coherent logic for tourism, locally as well as globally. In fact, the biennale became a medium for the re-imagination of Muziris as that desired cosmopolitanism that stretches the temporality, and thereby histories of people, much further back in time. Kochi-Muziris Biennale’s premise is set in this imagination, where the biennale returns every two years with a vision for future that resembles the past. There is a sense of nostalgia too, nostalgia that can’t really be touched or reached but is there to set the cards of future against.

Jithinlal N R, Chathippunilangal / Swamps, 2022. Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2022

Nathalie Muchamad, Non-Aligned Non-Alienated, Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2022

In addition to pulling on the histories from the sea and grounding itself in the idea of a region, Kochi-Muziris Biennale’s decade-long identity has been built on offering, for example, an artist-as-curator model, the art mediation programme as a link between the audience and the curator’s vision, a considerable in-situ production as well as a rich art education programme. However, the biennale’s history has been equally informed by its financial instabilities, production and accountability issues and, to an extent, many environmental disasters that shook the people of Kerala in last ten years or so.

The grounding itself in the local of Kochi, in the imagined pasts of Muziris and at the same time using the format of a biennale to create a discourse—it is in this nexus that I read Kochi-Muziris Biennale’s specificity and materiality. I question the biennale’s form itself as a site of imagination and ask how its memory can be read. Is it as an event, because of its rupture-like recurrence every two years, or an institution that the ever-present issues of sustainability, accountability, and belongingness seem to reveal?

Amol K Patil, The Politics of Skin and Movement, Site specific installation, Kochi-Muziris Biennale, 2022

Now, the consequence of such a discussion of a biennale’s foundational narrative, format and memory is also determined by its contemporary art and curatorial vision. The proposal of the curator of the fifth edition, Shubigi Rao, of biennale as commons, when read together with visual artist Amol K. Patil’s conversation of the everyday body politic, marked a discourse where norms of representation and spectatorship were upended. Patil’s work did not only display caste and class realities but also pointed to the spectator’s active role in reproducing them. By insisting on the labouring body’s histories and present, ‘The Politics of Skin and Movement’ kept adding fire to the uncomforting question of how the commons are actually shared and asked - whose cosmopolitanism is being re-imagined?

Konsthall C

In 2004, Hökarängen, a southern suburb of Stockholm, Sweden, attracted an experimental artistic intervention called Konsthall C that shared half the space of the neighbourhood’s community laundry hall. It garnered support from its local and informal Hökarängen District Council and public real estate agency Stockholm Homes, where Konsthall C and the laundry are housed even today. Konsthall C’s context was formed at the time when relational aesthetics and socially engaged art practice was the conceptual norm to experiment with. So, while it still carries the elements of being an art experiment, Konsthall C today is a small-scale art institute that has inherited the neighbourhood’s archives as well as a micro-institution called Centrifug within its gallery space, keeping the dialogue of autonomy and participation churning like the laundry wash cycles.

Omar Victor Diop, Albert Badin, 2014. Under A Different Sun. Photo Johan Österholm, Konsthall C Archive.

Drawing largely on the socio-political history of urban design, the people’s home (folkhemmet) and the people’s movement (folkrörelsen) in Sweden, and with a belief that cultural participation will ultimately translate into representation in public spaces, Konsthall C expanded on the social contract of Swedish democracy and modernity. According to one of its founders, being embedded in folkrörelsen, conceptually and in practice, means building spaces where people can meet, experience culture, and learn how to behave in a democratic way. It even developed a model of reinventing itself every four years by changing the institution’s artistic director, so that each time the new curator develops a ‘new’ relationship with the neighbourhood. However, with that proposition of staying contemporary, the cycle of re-imaginations that is, what remains hidden is that contemporary art institutions’ identities are still shaped by and intertwined with imaginaries that minutely as well as broadly frame the institution. One is the long-lived imaginary of folkhemmet that travels temporally in nostalgia and utopian future and is easily exploited by the popular consensus. The other is the broader or deeper imaginary of colonial and racial structures that inform the social contract of Swedish modernity as well as the foundations of Swedish art history. The former is celebrated loudly and the latter remains subtle and ignored.

Now, these imaginaries also get picked up, translated, mediated, negated or challenged in myriad ways by each curatorial practice, and that diversity of curatorial forms the layers of Konsthall C’s institutional memory. At the time of my fieldwork at Konsthall C, the curator Ulrika Flink’s curatorial program exposed the exceptionalism, extraction, and ahistoricity that determine the field of contemporary art in Sweden. With a curatorial practice that can be better understood as a cultural relational practice, Flink worked with methods of witnessing and listening to illustrate how the histories of our rights and identity are entangled with the binary of individual versus collectivity. In other words, how the violence of erasure or denial of race, queerness, and indigeneity has built Swedish belongingness in specific and affiliation to modernity in general.

The Otholith Group, Infinity minus Infinity, Videowork 2020, Under A Different Sun. Photo by Johan Österholm. Konsthall C Archive.

Lukaza Branfman-Verissimo, As Bright as Yellow, 2020. Under a Different Sun. Photo by Johan Österholm. Konsthall C Archive.

But what further complicates these already several intersections of conflicting imaginaries at Konsthall C is that a curator’s relationship with Konsthall C, and towards Hökarängen, remains bound to a contract of temporariness and peripherality. Hökarängen as a suburb has been a testing/trial/innovation ground for many ambitions of the county of Stockholm as well as Sweden as a nation. And when it comes to financial support from the public sector as well as the legitimacy of curators and curatorial knowledges in Sweden, much remains overlooked. So then, how are we to read these local and global intersections in the processes of memory building at Konsthall C, along with the circumstances specific to Hökarängen and Sweden?

To arrive at an explanation, I identify and conceptualise the existence of a deep trench between institutional, curatorial, and artistic practices. It is not to suggest that they are three separated poles, but it is an attempt to trace the kind of dynamics that contemporary art institutions, curatorial and artistic practices together create. It helps highlight the inquiries that certain artistic and curatorial practices are raising, such as who gets excluded in reimaginations, representations, and in supposedly shared visions. More importantly, to delineate how these practices are related to each other through their negotiations with the existent hegemonic rules within the field. Because by throwing a spotlight on such negotiations, what comes to surface is a reality where the existent tools cannot be used to read and understand representation and collectivity. One cannot use subject-object as a frame of reference to speak of representation and identity. Likewise, one cannot separate ‘my’ history from the history of ‘others’ to understand individuality.

All of this also shows the influence of modernity on contemporary art, its practices, and its institutions. Several recent studies in both decolonial and postcolonial thought have studied it as a ‘globalisation of contemporary art,’ showing how contemporaneity cannot be detached from ideas and processes of modernity.4 Their exploration on discovering the meaning of our ‘historical present’ has created a repository of artists’ and curators’ interventions from major fields around the world. In line with decolonial thought and praxis, my engagement with the spatial and temporal lock in contemporary art institutions of Kochi-Muziris Biennale and Konsthall C advances how certain contemporary art practices are moving beyond questions of representation and performance. Both cases present practices that restore the temporal continuity of the ‘past of others,’ which is otherwise systematically reduced to fragments.

Not just my case studies but other such critical works5 also show ways of understanding the specificity of location, bodies, and lived experiences in relation to the global. Their suggested methods on recollecting pasts, presents, and futures have served as critical flag posts from where I refocus attention on how multiple temporalities are experienced, claimed, denied, or exist in relation.6 Therefore, to critically interrogate the influence of modernity in the shaping of contemporary art means disrupting conventional notions of a re-imagined globality.

The problem, as I see it, is that the absolute foundation of the global itself is not challenged enough. The desire for a coherent narrative of the global is fundamentally rooted in a colonial, imperial, extractivist and deeply hierarchical vision of the world. In fact, categories and binaries such as local-global and ‘global south-global north’, or the assumptions that these binaries carry, are simply reflective of the existing temporal and epistemic hierarchies in the hegemonic understanding/definition of the global. So, what needs to be questioned is the assumed neutrality and wholeness of the idea of ‘global’ in contemporary art.

One way to do that is by foregrounding the present as a contested site in contemporary art discourse, an urgent and often ignored argument. And by staying with the present, I mean challenging the dominant temporality that currently underpins global art discourses, dismantling the rigid binary of local versus global, and advocating instead for an approach that recognises the complexities and entanglements of contemporary artistic production. A glimpse into that approach would be, for instance, to recognise that playing this contemporaneity and globality is also important for artists, especially those who have anti-caste and anti-race practices. Because if these works existed outside of the visual language of globality, they would easily be deemed irrelevant or illegible. For this reason, my intention with reading these case studies the way I do is to build a critical frame of reference for artworks and institutional practices that translates and mediates the present injustice of casteist and racist realities into specific visual and aesthetic languages.

My examples or case studies are not offered to be seen as solutions to the aforementioned structural hierarchies of the society, but they are to be read as propositions or seeds of possible nuisances. At best, they show a way to talk about spectatorship, representation, commons, and collectivity by bringing relationality to the core of our discussions. And, listening to their proposals on how different forms of relation can potentially take us beyond the binaries entrenched within modernity.