Kosisochukwu Nnebe, A Palimpsest for the Tongue, Photo by Ben Yau

Golrokh Nafisi (b. 1981, Isfahan, Iran) is an illustrator, animator, writer, and contemporary artist based between Amsterdam and Tehran. Golrokh has studied at the Art University of Tehran in Iran and at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in the Netherlands. She has frequently exhibited her work in galleries, as interventions and performances, and at film festivals, among which Art Rotterdam in the Netherlands, MACRO in Italy, and the Beirut Art Center in Lebanon.

Walking into Shapeshifters (2025) at Framer Framed feels, like stepping into a museum that is quietly remaking itself. The fabric walls soften the architecture, transforming the space into a modest, pliable museum—one that breathes. Within these supple boundaries, a lively dialogue unfolds among the works of twelve artists. Their gestures, materials, and stories form a dynamic constellation, each piece leaning toward the next, seeking connection across the soft contours of the exhibition.

Borrowing its title from Octavia E. Butler’s narratives of metamorphosis, the exhibition summons the idea of “shapeshifting” as an invitation to collective transformation. It extends Framer Framed’s long-standing commitment to unsettling and reconfiguring museum narratives—stories that have anchored the foundations of colonial heritage. Shapeshifters grows from this ongoing resistance, aligning itself with the four-year research project Pressing Matter, which investigates the value, ownership, and future of colonial collections.

In many ways, the exhibition becomes a visual translation of layered academic thought—a gesture that mirrors Framer Framed’s ethos: to bring critical research, artistic practice, and social inquiry into a shared, accessible, and evolving space.

GOLROKH: I’d like to begin with this exhibition. As we know, here in the Netherlands the conversations around restitution and cultural heritage are particularly resonant. Your work is shown alongside that of twelve other artists. How do you perceive the dialogue unfolding between your works—through harmony, through contradiction, or perhaps both? And what is the experience like for you, taking part in this collective presentation?

KOSISOCHUKWU: I think that in a lot of ways, my work seems almost out of place because it’s not dealing directly with those issues, the looting of cultural objects, the restitution of them, and so on, whereas some of the other works deal with that more directly.

My research looks at food as a counter-archive of colonial history. By following the movement of crops, recipes, and foodways, you start to see how enslaved people carried not only their bodies but their expertise. Yet in most historical diagrams—the triangular trade, the Columbian Exchange—we track the movement of goods, people, and plants, but never the movement of knowledge.

Take cassava: historically it was poisonous unless processed correctly. The plant could travel, but without indigenous knowledge it was useless. The same is true for bananas, which originated in Oceania and Southeast Asia, moved to Africa, and reached the Caribbean and South America through enslaved Africans who already knew how to cultivate them. That story is rarely told, even though their knowledge shaped global agriculture long before bananas became a commercial crop in the 19th century.

For me, the dialogue in this show is about widening what restitution can mean. It’s about recognizing the histories of indigenous and African knowledge systems that travelled, transformed the world, and yet remain largely unacknowledged. My work tries to foreground that, and that’s what makes participating in this exhibition particularly meaningful for me.

Kosisochukwu Nnebe, an inheritance / a threat / a haunting, 2022, Photo by Justin Wonnacott

I want to go back to the idea of ownership and also talk about your background in economics. With your example of the banana, I feel you’re speaking about a different kind of ownership that doesn’t immediately come to mind when we talk about “ownership.” Now, with movements like Land Back, people are beginning to understand issues of property and recognition, but what you’re saying goes one layer deeper: you’re talking about knowledge—indigenous knowledge.

I’d love to hear about your journey: studying economics, then encountering contemporary art, and eventually arriving at this strong visual language that allows you to transmit knowledge. Can you speak about that journey?

I’ve found that economics was important to me because it trained me to simplify complex ideas—to work with diagrams, axioms, and foundational structures that you build on and rearrange. At the same time, I’ve had to unlearn many of its assumptions, which helped me understand what to question and what to push back against. But what really shaped how I work was my eight years in policy. Policy forces you to be concise, accessible, and convincing: you take a huge amount of research and translate it into something clear and actionable. That discipline now shapes my art. My work has to communicate, it has to break complexity down, and it has to be persuasive.

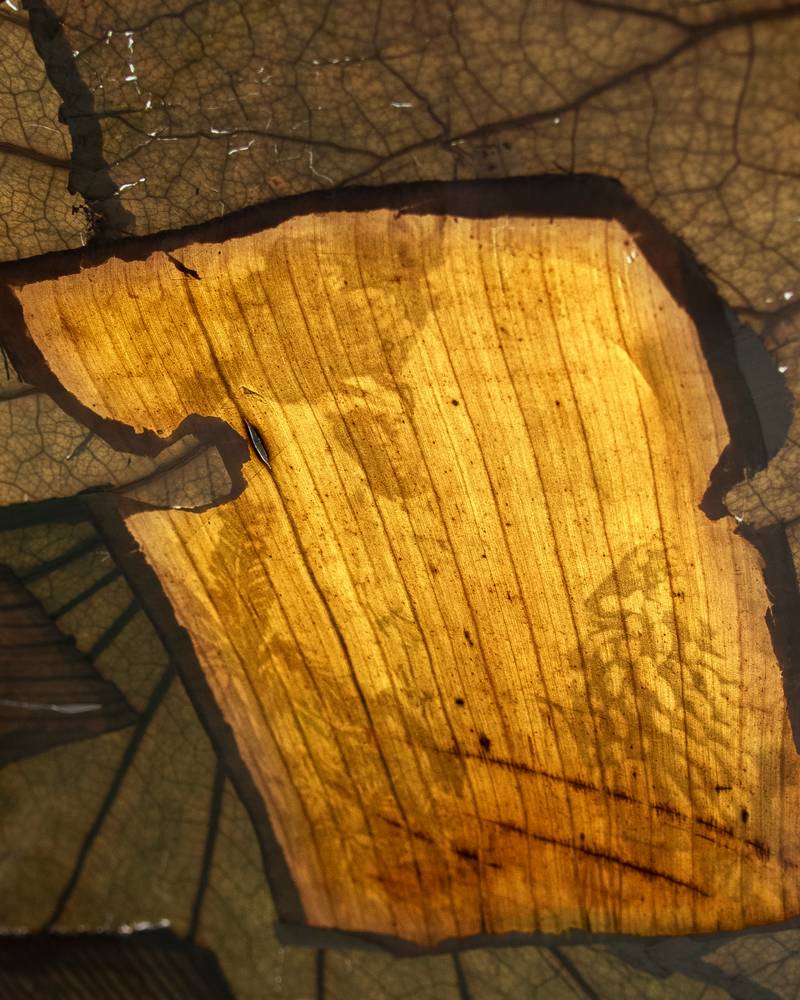

Art, though, allows me to do what economics and policy can’t—it lets me engage people directly, even physically. That’s why I’m drawn to installation. With the banana piece, for example, I’m not only presenting archival images; I’m trying to recreate a memory from being in banana groves in Jamaica and Nigeria—the sun filtering through the leaves, that sense of intimacy. I want to counter the colonial logic that reduces the banana to fruit or aesthetics alone, erasing the centuries-long experience of actually living with the plant.

My background in economics still helps me understand how others perceive value, and I use that to make visible the forms of value that have been dismissed—especially Indigenous and African knowledge systems. I often work through parallels: with cassava, for instance, the knowledge of how to prepare it, which enslaved people carried, became visible to slaveholders because it threatened their control. That tension reveals whose knowledge has mattered and why.

Even elements like the shadows in the installation—which emerged naturally from the lighting—speak to this play of value and perception. Historically, the banana leaves themselves were considered more valuable than the fruit because they provided shade for crops like cacao and coffee. These shifting ideas of value, and how they shape our relationships with plants, people, and histories, are central to how I make work.

Kosisochukwu Nnebe, A Palimpsest for the Tongue, Photo by Ben Yau

I want to move to the idea of the archive. We all know we need to shift how we think about archives, because everything we have is essentially a colonial archive. There seem to be two approaches: one says, “Let’s add our stories to the existing archive.” The other is more radical and says, “We need to change the entire idea of the archive.”

In many of your works—and in your printing techniques—I see something closer to this second approach: rethinking what an archive can be. Do you think that’s an accurate interpretation?

I think so. I think the way I approach archives is that I don’t necessarily work with them. For example, the photographs are obviously from somewhere, but what I’m trying to do is to draw attention to the food itself, like the crop itself as an archive that reveals different stories. That’s one way of getting away from this emphasis on having access. People often ask me, “Which archives have you been to?" I don’t really do that. I’m not trying to access the National Archives, because there’s always this thing of power and control and authority and seeking access to something to then uncover what’s always been missing.

Instead, what I try to do is use cassava—much like I use the banana—as a way of drawing out different narratives and counter-histories. The banana remains one example, of course, but cassava, and the story I am telling through it, offers a layered sense of connection across geographies and across time. Cassava is indigenous to the Caribbean and South America, and I have been focusing in particular on Jamaica, where its histories and transformations continue to resonate. For me, cassava shows how Indigenous knowledge has always been central—not just to make the crop edible, but also to transforming it into poison. In Jamaica, the Tainos shared this knowledge with the Spanish, the British, and with enslaved people. That transfer shows up in colonial botanical catalogs, which were created out of fear and surveillance. In one description, the recipe for the poison begins with Indigenous practices and ends with a warning about enslaved people using it—revealing a quiet slip in the archive where knowledge passes between communities. That gap hints at a kind of cross-cultural solidarity that was never considered important enough for colonizers to document, but it’s there if you look closely.

That’s what I try to excavate: the way everyday materials, like cassava, carry histories of resistance, collaboration, and survival. The crop itself becomes an archive. And when I work with archives, I don’t reject them, but I try to close their gaps through imagination and embodied practice. For this project, I actually replicated the steps for making cassava poison myself. Through that labor, I tried to imagine the emotional world of enslaved women—what circumstances would drive them to prepare it. That process gave me a deeper understanding and shaped the body of work that followed. My approach to archives is grounded in food, physical experience, and imagination, using these to reach toward the lived histories the documents can only hint at.

Kosisochukwu Nnebe, A Palimpsest for the Tongue, Photo by Ben Yau

I wonder how you moved between these lenses—classical colonialism and settler colonialism—and then back again, especially since you’ve also traveled to South America. I feel you are tracing routes in reverse, like a fish swimming back upstream. And now you’re in the Netherlands—one of the historical sources of colonial thought. Can you tell us about this journey—this movement against the current?

It’s a good way of describing it. A lot of it is simply trying to get back home—the place I left when I was five. It feels like a return, but through the wrong path, one shaped by the experiences I’ve faced in migration. Even with the foods I work with, I am always moving in almost the opposite direction. When I moved to Canada—flying into North America—my main identity suddenly became one of Blackness. I spent a lot of time engaging with the works of thinkers like Frantz Fanon to understand the process of racialization.

In Canada, I found that conversations around who counts as a “settler” lacked nuance, especially given the heterogeneity of Black identities—refugees, recent immigrants, descendants of Loyalists, and so on. My work focused on Black–Indigenous solidarities, especially through shared losses of language caused by both settler colonialism and neocolonialism. But I also felt a dismissal of my own experience as an Indigenous African displaced from her land, even though I recognize that these histories of dispossession are not the same. The goal, for me, is not to collapse the differences but to build solidarity from the shared ground we can identify.

That is where this desire to understand the differences comes from, but also to create opportunities to show what is, what has traveled, and what has been shared. And again, this is indigenous knowledge that is traveling. It has been the way we’ve kept each other alive, something we’ve lost sight of because of the ways in which archives are organized, the ways in which histories are told as if they have always existed in a fixed form. It is up to us to identify those moments.

Based on those experiences, I have found myself retracing, going back to Jamaica. I am returning with the intention of understanding those moments of exchange between enslaved people and Indigenous peoples, but also the ways in which Indigenous knowledge and African knowledge were retained. I was tracing that.

The reason I went to Jamaica is because I was trying to trace Igbo heritage there, and it is one of the strongest places. Oftentimes, Nigerian heritage is referred to as Yoruba, so the Orishas and all of that are Yoruba cultural heritage, not Igbo. I went to Jamaica specifically for that. I am trying to understand the ways in which knowledge, language, and other forms of cultural memory have been retained and reformulated, and all of that is part of going back home.

I want to finish with the word “transformation,” because I think there is hope in that word. Every work in this exhibition has some form of transformation or hope in it. You went from economics to politics and now to art.

What is your horizon of hope?

That’s a really good question. What is my hope? Because I do have a lot of hope—I wouldn’t be doing this work if I didn’t. A lot of it is rooted in a deep love for Black women. That’s the consistent thread, and a deep admiration for the ways in which, even in their suffering, they have found ways to sustain community and sustain themselves.

Even in the work here, many of the images are of market women in Jamaica. I think it’s a fascinating history, because so often—whether through the Chiquita Banana label or old postcards—Caribbean women have been exoticized: the woman with fruit piled on her head, the stereotyped imagery repeated over decades. But the real history of why so many market women dominate food markets in the Caribbean comes from slavery. Enslaved people were often given small plots of land to tend on Sundays, growing crops like bananas, and allowed to sell the surplus. These moments created pockets of financial autonomy within oppression.

Colonial narratives, however, warped these histories, fetishizing these women, printing their images on postcards, and erasing the real story. I’m interested in uncovering these histories of ingenuity and resilience, how Black and Indigenous peoples made something out of nothing—and connecting them to the present. My work asks, what can we learn from these acts, and how might they shape the way we engage with each other today?

I have learned so much from the histories I engage with. I am transformed by them, and that transformation guides my work. There’s a playfulness that emerges out of scarcity—this idea that if resources are few, you improvise. You take something like cassava, which is meant to feed you, and you turn it into a weapon. The way they would bring it into the home was by packing it under their thumbnail, turning the thumbnail itself into a weapon. There is humor in that. And that sense of humor, I think, also comes through in my work.

It’s a reminder that if they could do it, we can as well. And I’m all for burning things down, truthfully, I really am.

Thank you for sharing this beautiful horizon with us.