Liisa-Irmelen Liwata, Exhibition view, Still I Rise, Kunsthalle Seinäjoki, Photo: Krista Luoma

Elham Rahmati (b. 1989, Tehran) is a visual artist and curator based in Helsinki. She is the co-founder and co-editor of NO NIIN. In 2019 and 2020, she worked as the curator and producer of the Academy of Moving People & Images (AMPI), a film school in Helsinki for mobile people.

Vidha Saumya (b. 1984, Patna) is a Helsinki-based artist-poet. She is the co-founder and co-editor of NO NIIN – an online monthly magazine in Finland, and a founding member of the Museum of Impossible Forms – an award-winning cultural para-institution in Kontula, Finland.

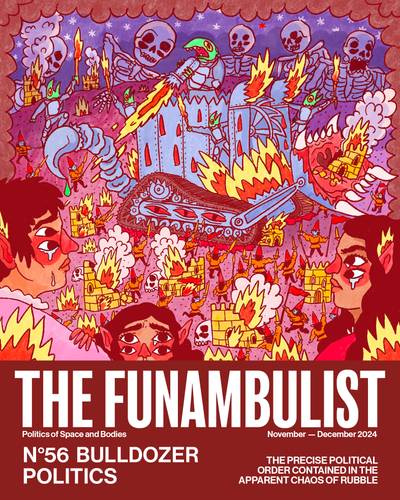

Liisa-Irmelen Liwata’s work turns inward and skyward. Rooted in the concept of napa—the Finnish word for “belly button”—her practice explores the navel as both physical origin and central point of orientation. This duality becomes a metaphorical compass, guiding an exploration of cultural identity, bodily memory, and belonging. Through symbolic instruments of navigation—compasses, celestial charts, and “belly button stars”—Liwata constructs a personal cartography. Her work traces constellations in the Finnish and Congolese sky, mapping parallel cosmic landscapes that reflect her own hybridity.

With Liisa-Irmelen, we—the curators of Still I Rise, currently on view at Kunsthalle Seinäjoki—discuss Finnishness, heritage, and the material transformations that shape her work, questioning both physical and conceptual borders along the way.

VIDHA: Your new work incorporates the motif of belly buttons. What inspired you to explore this part of the human body, and what significance does it hold for you in the specific context of this exhibition?

LIISA-IRMELEN: I’ve been fascinated by napa, which is the Finnish word for “belly button”, for quite some time, and it has become a core theme in my work. Over time, it has become more prominent in my pieces. What initially drew me to the word was its dual association with both the human body and a central point in general, extending even to the Earth’s poles, the North and South Poles. These connections between the body and the land have intrigued me, especially in relation to my cultural identity.

I describe it as having multiple belly buttons, various points of navigation in the world. This concept translates into a sense of orienteering, of positioning oneself in the world. In this exhibition, I focus on the theme of orientation, incorporating elements like the compass and “belly button stars,” which serve as symbolic tools for navigation.

Additionally, I include two different star constellations, one representing the stars visible in the Finnish sky and the other representing those seen in Congo. In this way, the work explores the merging of the body with the Earth, connecting personal identity with geography and celestial navigation.

V: The concept of parallel realities is central to your work. How do you navigate and represent intertwining realities, and what significance do they hold in understanding your personal identity?

This is a complex question. My work explores the relationships between the body, nation, and nature. A key starting point for me has been the idea that, to develop a more sustainable relationship with the environment, we must also question our sense of ownership over land. This, in turn, leads to a broader rethinking of our connections to each other, to nations, and to the concept of national identity, where land is seen as a fixed, owned territory. Instead of being tied to a specific area, could national identity be understood as a more porous and flexible concept? And how would that affect our relation to the land?

Through the presence of the body, land, and nature in my work, I aim to embody a sense of transformation. There is always some form of movement, whether it’s the process of decay, where the body becomes the land, or the reverse, where the land takes on bodily qualities. I incorporate both abstract and figurative elements to convey this transformation, creating a space where these boundaries blur and shift.

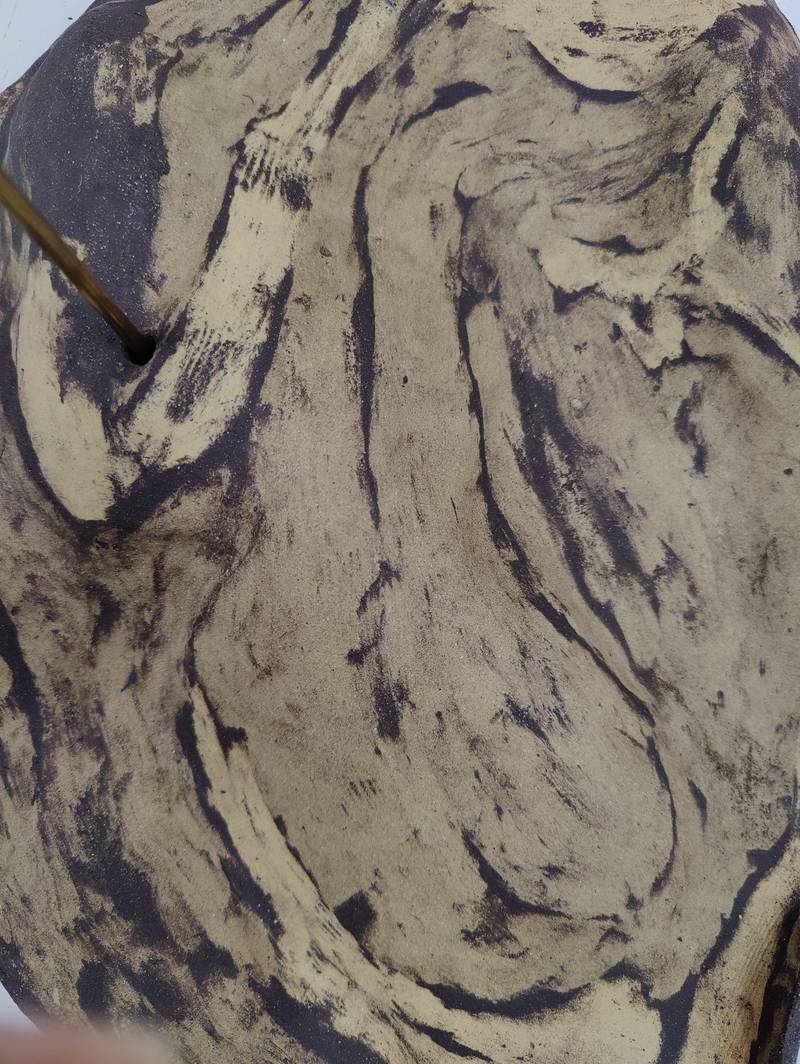

Liisa-Irmelen Liwata, detail view, Still I Rise, Kunsthalle Seinäjoki, Photo: Krista Luoma

ELHAM: If we go back a bit, before you started thinking about belly buttons, was there something that first led you to critically examine the idea of the nation-state and one’s connection to the land? Have you considered how this concept relates to current global events, such as the rise of nationalism and, more specifically, white nationalism? Has this broader context influenced your thinking in any way?

Sure. It started when I began my studies at Kuvataideakatemia in 2019. These ideas, along with my personal experiences, have shaped my perspective, especially my experience as a Finnish citizen abroad and the need to explain my Finnish identity both internationally and within Finland.

These personal experiences, along with the global political climate, have influenced my thinking. Around 2018 and 2019, there was a lot of discussion about migration, particularly at the Greek borders, which deeply affected my perceptions of others, otherness, and the idea of “us” versus “them.”

E: When you received the invitation to exhibit in Seinäjoki, a place with its own specific political and cultural landscape, did you consider this context while developing your work? Or was this something you intended to present regardless of location?

First and foremost, I created this work for my enjoyment and to express what I personally wanted to share. Of course, the location where the work is being shown has been a consideration, but it hasn’t been the most significant or defining factor in my creative process.

Liisa-Irmelen Liwata, detail from the work

Liisa-Irmelen Liwata, detail from the work

E: How do you translate the concept of ‘ancestral connections’ into the tangible, tactile qualities of your ceramic works?

For me, this connects to another Finnish word for land, maa, which refers not only to the land itself but also to earth, soil, and even the nation. Just working with this material carries meaning for me; it becomes a way to describe and shape these works.

In relation to ancestry, I am returning to the idea of transformation, particularly the transition from one state of being to another, especially in terms of decay. This theme has been on my mind a lot in recent years: the body dissolving into the earth, and the earth, in turn, carrying fragments of that existence elsewhere. Whether it’s soil or sand, these elements travel across borders, moving between places and nations, representing something beyond their point of origin. I’m thinking about this cycle of transformation of being, in a way, absorbed into another land, another nation. It’s about decay, returning to the earth, and then being reshaped by it once again.

E: In your artistic practice, you raise the question of whether new landscapes could reveal new ideas about nationality. What role do you think contemporary artists like yourself can play in reimagining national identity in the modern world?

Well, I think about this a lot because it’s interesting how the concept of Finnishness was shaped by artists and writers during the 19th century, particularly during the era of national romanticism. For me, this is an important tool, especially considering that, at that time, Finnish identity was closely tied to the landscape and nature to form a unified national identity, in contrast to the drive toward independence from Russia. That’s why I find it meaningful to incorporate elements of nature in my work. In a way, I’m revisiting and reinterpreting this historical connection, using nature again to explore and express ideas of nationality, but from my own perspective.

E: Apart from the connection to land and nature, what do you personally associate Finnishness with? Are there particular traditions, values, or experiences that feel especially tied to your sense of Finnish identity?

It’s interesting and also challenging to separate my own personal thoughts from the more branded or constructed ideas of Finnishness that have been instilled in me. But I would say that certain cultural traditions are a big part of it. It’s a difficult question, though, because I’m constantly questioning my understanding of Finnishness, wondering if what I think is truly authentic or just something I’ve been taught to believe.

E: I’m interested in knowing whether this has been a process for you and whether it’s still evolving. Where did you start? What questions have you been asking yourself to help define and, perhaps, redefine what it means to be Finnish?

I feel like now, when I’m in Finland, it’s easier to reflect on my relationship to Congo and to my father. But when I think about Finnishness, I find it more difficult; it’s almost like it’s too present, too close to me, and I’ve become blind to it. I wonder if being farther away from the country might help me gain more clarity and a better understanding of what Finnishness truly is.

Liisa-Irmelen Liwata, Exhibition view, Still I Rise, Kunsthalle Seinäjoki, Photo: Krista Luoma

V: Going back to the question of nationality, when you were talking about connecting the definition of Finnishness or Finnish national identity to the 19th century and the role of nature and landscape in defining it, I was curious: when you hear the term “national identity,” is Finnishness the first thing that comes to mind? Or do you think of national identity more broadly, beyond the borders of any one nation? What are the associations that come up for you? And in connection with Elham’s question, when we question or think about our relational identity, what are the things we ask ourselves to determine what we feel connected to, what we identify with, or what we reject? Do these kinds of thoughts cross your mind?

I’ve started thinking about national identity through Finnishness because it has been the easiest way to access references, literature, and resources here. But over time, I’ve also begun considering it from a Congolese perspective. The truth is, I don’t really know how Congolese people would define their national identity, how strong it is, or what elements might be associated with it.

More broadly, I find it interesting to explore the concept of national identity within the African continent. Unlike Finland, where people have had the opportunity to define Finnishness for themselves, many African nations had their borders and identities imposed on them through colonial history. In Africa, national borders were drawn without regard for the existing ethnic groups, which continue to exist despite these artificial divisions. It would be fascinating to research whether national identity in Africa is more closely tied to ethnic identities or to the nation-state, and how those two aspects interact or balance each other.

I’ve also been thinking about national identity in the context of war. When a state is under attack and must defend itself, national identity becomes much clearer and more urgent. In contrast, in Finland, where we are not currently experiencing an immediate crisis, it is easier to question the role and necessity of national identity from such a privileged position. I’ve been reflecting on this in relation to places like Palestine and Ukraine, where national identity is deeply tied to survival and resistance. It makes me think about how different circumstances shape our relationship to identity and belonging.

E: Working with ceramics as your canvas, you explore the impact of displacement and heritage. What emotional or intellectual journey do you hope your work initiates for viewers experiencing this exhibition?

For me, it’s just as important whether someone fully understands the work as it is that they experience it visually. I believe the conceptual ideas will reveal themselves naturally to the viewer over time. It’s open-ended. I don’t expect everyone to grasp the exact ideas I’m trying to convey immediately. What matters most is that the work sparks questions in the viewer. Rather than providing clear answers or dictating a specific way of seeing the world, I hope it leaves room for curiosity, reflection, and interpretation.

Liisa-Irmelen Liwata, Exhibition view, Still I Rise, Kunsthalle Seinäjoki, Photo: Krista Luoma

E: What new territories or concepts are you excited to explore in your future works?

Lately, I’ve been more interested in exploring the materiality of my works. I’ve been incorporating different earth materials that share similar elemental properties, such as clay, sand, and rocks, which exist in earlier states before clay forms through erosion and decay. At the same time, I’ve been working with glass, which represents another transformation: sand and rocks melt into something entirely new.

These material shifts and transitions are central to my work, mirroring broader ideas of change and transformation. Beyond the materials themselves, I’m also thinking about national identity, particularly in relation to African perspectives on it, which I continue to want to explore further.

E: What kind of reading materials have you been engaging with? Have you read or watched anything in particular that helped you explore the ideas present in this work and exhibition?

Yeah, well, regarding Finnish national identity, I’ve read some literature on the topic, though I don’t remember the exact titles. But one book I often return to is Bantu Philosophy, which belonged to my late father.

It’s not necessarily tied directly to nationality, but another book that has influenced my thinking is Pure Colour by Sheila Heti. There’s a moment in the book where the narrator describes her father, after his passing, transforming into a leaf. I think that kind of animistic perspective has, in some way, found its way into my own unconscious thoughts as well.