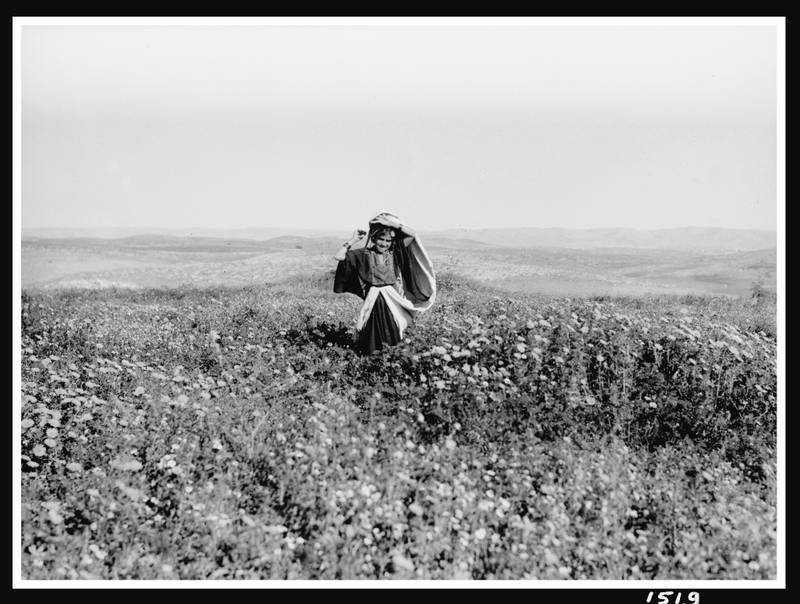

Image 12, American Colony, Lewis Larsson, and American Colony Photo Department. American Colony in Jerusalem Collection: Part I: Photograph album, Locust plague of. Jerusalem, Palestine, 1915. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/mamcol.058/.

Ahmed Alaqra is a Palestinian artist and curator whose practice of unmaking reconsiders architecture, landscape, and image-making as acts of reclamation, revealing the processes within the habitual and the everyday.

Following my arrival in Stockholm in mid-September, I had planned to focus on the technical side of my photographic practice, particularly long exposure, to explore how time could sediment into the image. Yet I quickly found myself pulled elsewhere, toward a more fundamental question: not how to photograph, but why, and from where.

A visit to Fotografiska in Stockholm sparked this shift. Three exhibitions of white European photographers, each narrating the world through what I would call a Eurocentric lens—which is understandable in the context I was in—left me questioning the historical practices of Swedish photographers. This inquiry led me far from Sweden to nineteenth-century Jerusalem, and particularly to the Eric Matson Archive, where photography was entangled with theology, empire, and myth.

The American Colony and the Sacred Image

In 1881, a group of Christian Protestants from the United States, led by Horatio and Anna Spafford, established the American Colony in Jerusalem, imagining it as a Christian utopia where faith could be lived in proximity to the Holy Land (Kark & Ariel, 1996). By the 1890s, they had set up a photography department that would become one of the most famous visual repositories of Palestine (Gröndahl, 1998).

Among their central figures was Lewis (Lars) Larsson, a young Swedish photographer who joined the Colony at the age of sixteen and remained active through the first decades of the twentieth century (Gröndahl, 1998). His collaboration with Eric Matson later produced what is now known as the Eric Matson Collection, preserved at the U.S. Library of Congress, a monumental archive of the so-called “Bible Lands.”

This archive, often treated as documentary, carries what historian Issam Nassar (2002) calls “the missionary gaze,” a way of seeing that fuses revelation and record, rendering the landscape not as land but as scripture. The Colony’s photographs were meticulously organized into albums that mirrored biblical narratives, including Bethlehem and Shepherds’ Fields, Scenes from Galilee, and The Road to Jericho. The most striking among them, however, is the 1915 Locust Plague Album.

![Riding party, 1903, American Colony. Photo Department, John D. Whiting, Lewis Larsson, and G. Eric Matson, photographer. *Members and activities of the American Colony Jerusalem*. West Bank Israel Jerusalem Jordan Palestine Egypt Syria Middle East Malta Tadmur, None. \[Between 1890 and 1906\] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2007675258/.](/images/cmj73hk758kqt07um7fl6nlls-800w.jpeg)

![Riding party, 1903, American Colony. Photo Department, John D. Whiting, Lewis Larsson, and G. Eric Matson, photographer. *Members and activities of the American Colony Jerusalem*. West Bank Israel Jerusalem Jordan Palestine Egypt Syria Middle East Malta Tadmur, None. \[Between 1890 and 1906\] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2007675258/.](/images/cmj73hk758kqt07um7fl6nlls-lqip.webp)

Riding party, 1903, American Colony. Photo Department, John D. Whiting, Lewis Larsson, and G. Eric Matson, photographer. Members and activities of the American Colony Jerusalem. West Bank Israel Jerusalem Jordan Palestine Egypt Syria Middle East Malta Tadmur, None. [Between 1890 and 1906] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2007675258/.

The Messianic Vision and the Biblification of Territory

The American Colony’s work cannot be understood outside the messianic and millenarian theology that guided its founding. The Spaffords were deeply influenced by premillennialist Christian thought, which interpreted the Jewish “return” to the Holy Land as a divine prerequisite for Christ’s Second Coming. The Colony’s spiritual ideals were entwined with the emerging current of Christian Zionism that gained momentum in the late nineteenth century (Ariel, 2013; Kark & Ariel, 1996).

Within this theology, Palestine was not simply a place to inhabit but a prophecy to fulfil. The land was imagined as spiritually dormant, awaiting divine restoration. Photography, therefore, became an instrument of revelation—a means to visualize the Bible, to render faith visible through geography (Gröndahl, 1998). The albums and tinted prints that circulated in Europe and America reinforced a powerful narrative: that the land’s “redemption” was both scriptural destiny and moral duty.

This alignment between religious imagery and prophetic geography quietly prepared Western audiences to perceive Palestine as an empty spiritual stage awaiting the coming of the Zionist Jews, rather than a lived homeland. What appeared to be an act of devotion—the colouring of fields into biblical golds, the naming of sites after scripture—was also a political theology in practice. By visually sanctifying the land, the Colony’s photographs naturalized a worldview that would later echo in Zionist and missionary discourses alike, transforming faith into a form of proto-colonial mapping, a step among others that paved the foundation to the Occupation of Palestine and the establishment of Israel (Ariel, 2013; Kark & Ariel, 1996).

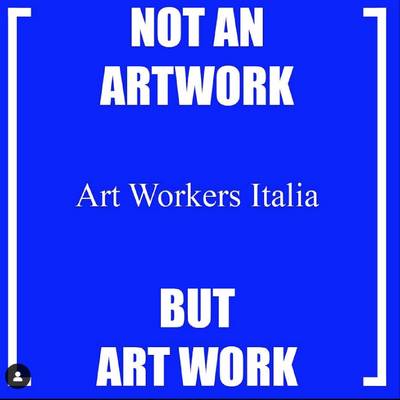

Image 1: American Colony, Lewis Larsson, and American Colony Photo Department. American Colony in Jerusalem Collection: Part I: Photograph album, Locust plague of. Palestine Jerusalem, 1915. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/mamcol.058/.

The Locust Plague: Nature as Divine Allegory

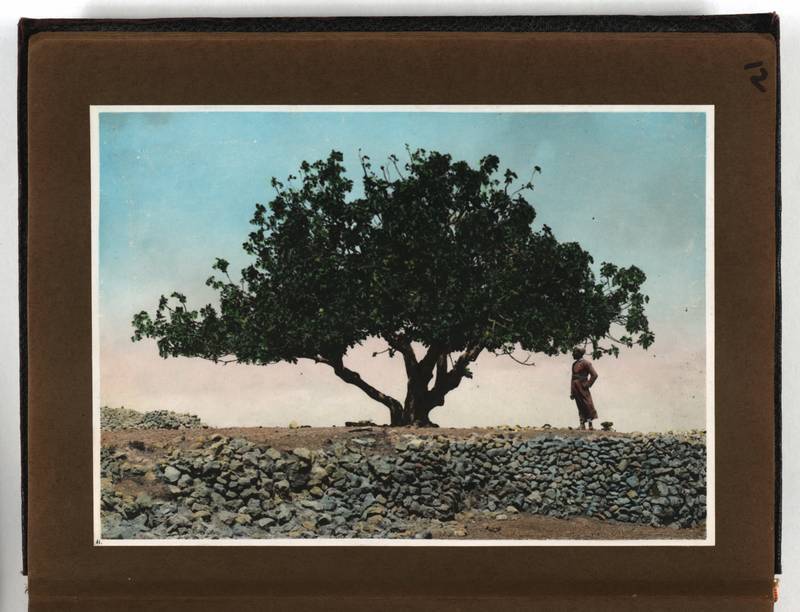

The Locust Plague of 1915, which devastated crops and caused famine across Palestine and Syria during World War I, was recorded by Larsson and the Colony photographers as both natural disaster and spiritual omen (American Colony [Jerusalem], 1915). Their album, titled The Locust Plague in Palestine, contains over fifty images documenting every stage: from the infestation of fields to darkening skies, from children gathering locusts to aerial views of barren plains.

Seeing these images, it becomes clear that Larsson and his colleagues were not attempting reportage but rather visualizing prophecy in a biblical land. For where else could a locust infestation be rendered as a “plague” if not on the land of God?

Looking more closely, one notices that although the photographs were accompanied by reports of agricultural and human suffering, the locusts were depicted not as insects but as biblical phenomena. The fields appear scorched in divine wrath. The horizon darkens dramatically, and figures are dwarfed beneath turbulent clouds, echoing apocalyptic imagery from Exodus and Revelation.

In this way, Larsson’s camera translates catastrophe into theology. His images perform a visual exegesis, transforming the local and ecological into the mythic and universal, as if every drought and every storm confirmed the Bible.

Image 13, American Colony, Lewis Larsson, and American Colony Photo Department. American Colony in Jerusalem Collection: Part I: Photograph album, Locust plague of. Jerusalem Palestine, 1915. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/mamcol.058/.

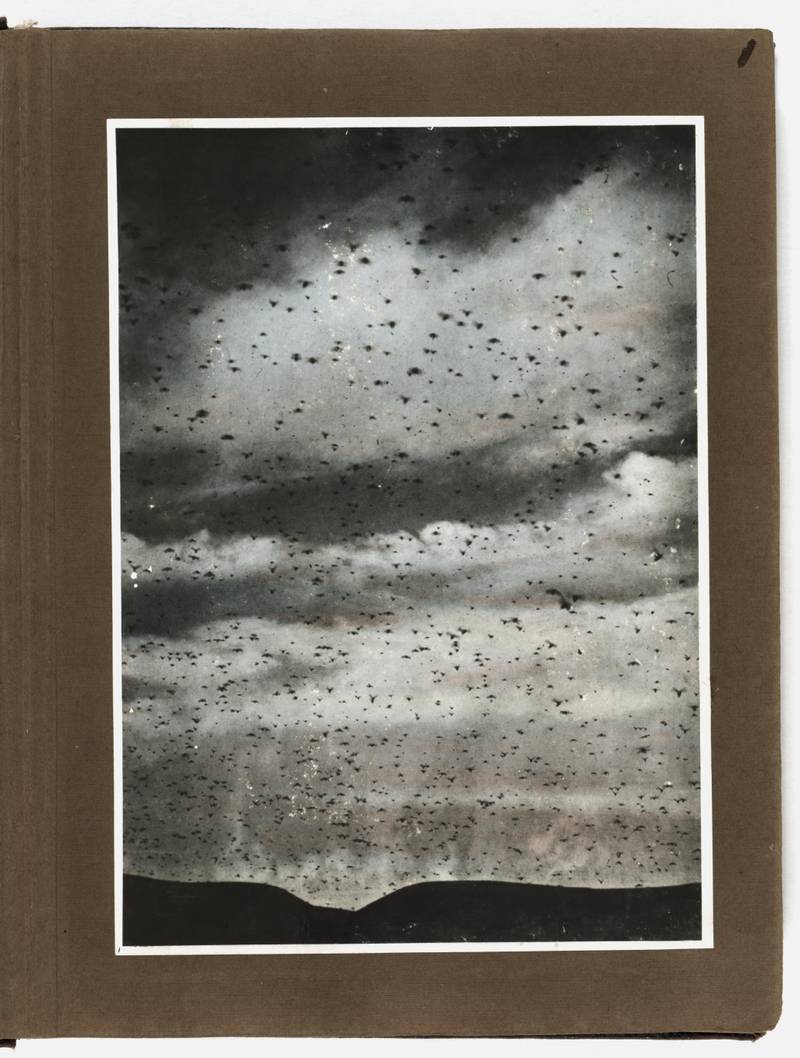

The Colour of the Divine: Hand-Tinting as Colonization

Originally shot on glass negatives in black and white, many of the Colony’s images underwent a delicate process of hand-colouring, a technique performed mainly by women within the Colony workshop (Graham-Brown, 1988). Using transparent water-based dyes and fine brushes, they tinted prints one by one, often referencing Western landscape painting palettes rather than the actual tones of Palestine’s soil and light. This process enabled them to project and impose certain visions onto the landscape. These colours were neither naturalistic nor arbitrary.

The skies were often tinted deep cobalt blue, the same hue used in European Romantic painting to evoke celestial vastness. The soil took on warm sienna or golden ochre, transforming dry earth into the “promised land” of abundance. Olive leaves gleamed in emerald green, even when the real landscape differed. Flesh tones were softened into idealized pinks, erasing traces of sun, labour, or ethnicity when needed, or left darker in other instances. The intention was not simply to show the opposite of the landscape, but to construct the Holy Land as it should appear to the European eye. This palette was not meant to reproduce reality; it was meant to redeem it (Graham-Brown, 1988).

By colouring the land through a European painterly spectrum, the Colony’s photographers effectively rebaptized Palestine in pigment (Gröndahl, 1998). The hand-tinting became a theology of light, with colour as revelation and dye as evidence of Eurocentric divine beauty, sometimes lush and green, and at other times reduced to relics of biblical sites and Bedouin dwellers.

As Sarah Graham-Brown has argued, such hand-colouring transformed documentary photography into a form of pictorial theology, creating images that reassured the Western eye that the Holy Land was still the land of faith, even if reality differed. The romantic hues covered not only the dust and desolation but also the colonial disillusionment that birthed them.

In the case of the Locust Album, this colouring takes on an even more paradoxical tone. The horror of famine is washed in aesthetic harmony; death glows under the same amber light as divinity. The manipulation of colour performs a subtle violence, where suffering becomes spectacle, calamity becomes confirmation, and a place becomes theology.

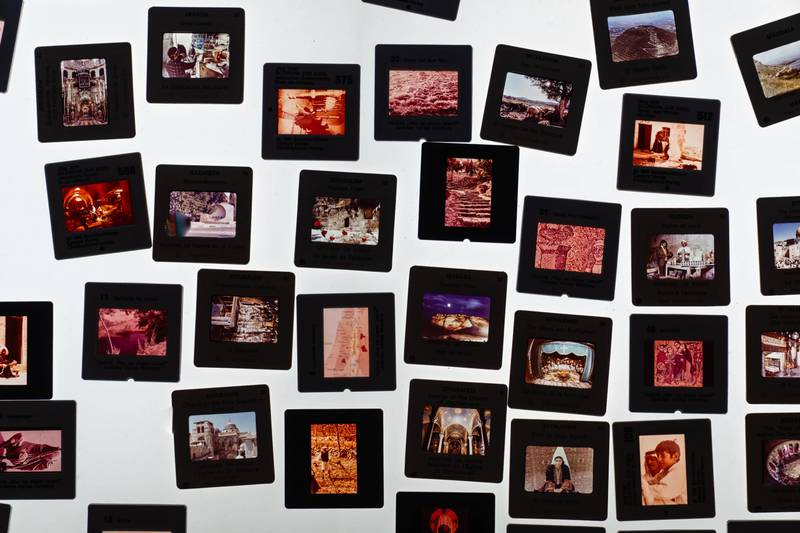

The American Colony sold these images widely as postcards, lantern slides, and illustrated albums, distributing them through their photographic bureau to tourists, missionaries, and publications such as National Geographic. The tinted images were not only devotional but commercial, functioning as souvenirs of belief and proof that one had “seen” the land of the Bible. Here, colouring becomes doubly charged: it bridges piety and profit, scripture and spectacle. It is not only aesthetic colonization but spiritual commodification, with the land made holy through pigment and then sold as image.

The Native Lens: Photographing the Everyday, Between Theology and Landscape

When one compares Larsson’s tinted locust scenes with local photographers of the same period, such as Khalil Raad or Daoud Sabonji, the contrast is profound, even if occasional formal similarities arise (Nassar, 2002). Raad’s street portraits and family scenes root the viewer in the everyday life of the city, not as divine but as habitable, situated within the temporal flow of ordinary existence. Larsson’s images, by contrast, suspend time and biblicize it.

Larsson’s landscapes exist outside history, in a perpetual moment of divine testing. The sky always gathers, the earth always thirsts, and the horizon always waits for salvation. If the American Colony’s images sought to sanctify the land, the early Palestinian photographers worked to humanize it, not as a counter-gesture, but as an affirmation of lived reality. Their gaze was directed toward the ground, streets, thresholds, and gestures, rather than heaven.

Khalil Raad, often cited as Palestine’s first Arab photographer, opened his studio in Jerusalem around 1890, a few hundred meters from the American Colony’s (Seikaly & Nassar, 2006). Yet his images belong to an entirely different world. Raad’s photographs do not seek revelation; they record habitation. His streets are not scenes of prophecy but of procession, with workers, shopkeepers, women walking through stone alleys, and children climbing walls. Where Larsson monumentalized landscape, Raad domesticated it.

Bethlehem Woman, Khalil Raad, 1918–35, Courtesy of the Institute for Palestine Studies.

Field of wildflowers, Khalil Raad, 918–35, Courtesy of the Institute for Palestine Studies.

In one of his images, a woman wearing the traditional dress of Bethlehem takes in the view of the Bethlehem hills*,* the figure stands at the edge of a rocky path, her embroidered dress tracing the local geography as much as the landscape itself. The photograph fuses posture and topography: the woman’s gaze stretches across the horizon, not as prophecy but as belonging. Unlike the missionary lens, which sought signs of divine promise in the land, Raad’s camera recognizes the sacred through continuity—in how the human body meets the hills, how fabric echoes stone, and how looking becomes a quiet act of dwelling.

In another image of Raad, a girl in traditional clothing standing in a field of wildflowers in springtime, the atmosphere shifts from stillness to renewal. The child stands amid the unruly bloom, her presence both delicate and grounded. Light falls softly on her face, and behind her the blurred field dissolves into colour and texture. The image resists allegory: spring here is not resurrection but rhythm, a seasonal pulse shared by land and people alike. Raad’s camera gathers this moment without imposing transcendence; his sacred emerges through the cycle, not revelation.

Through these scenes, Raad reclaims the photographic image from revelation and returns it to habitation. His work, though quiet, offers a profound counterpoint to the missionary archive: it speaks of a land that was never empty, a people who never ceased to live within it (Nassar, 2002).

Archives as Contested Territories

While missionary and colonial collections like the American Colony archive dominate Western institutional shelves of Palestine, retelling the history of the land over and over, the local photographic record has always existed in parallel (Seikaly & Nassar, 2006). Yet it remains concealed, intimate, fragmented, and dispersed. Family albums, studio portraits, and vernacular photographs, often tucked away in homes or private collections, offer glimpses into a Palestine that aligns more closely with the diaries and texts written by the land’s inhabitants at that time.

Initiatives such as Khazaen, the Palestinian Museum Digital Archive, and the Institute for Palestine Studies archives have allowed the local population to digitize and make accessible their private and familial collections of images over the past century. While still limited in number, these images offer another geography. Their narratives challenge the enduring myths imposed by outsiders. Access remains partial, but even fragments allow us to imagine alternative chronologies, counter-histories that prioritize the mundane, the habitual, and the lived.

A Photograph of Saadeah Bsoul, Jerusalem, Date unknown, The Saadeah Bsoul Collection, The Palestinian Museum Digital Archive.

Unbiblifying the Land in Contemporary Practice

Contemporary Palestinian photographers and artists build on this lineage by actively intervening in the archival record. The concept of “unbiblifying” extends beyond critique; it is a process of reclamation and reinterpretation.

In Rula Halawani’s Negative Incursions, for example, light and shadow are inverted, destabilizing photography’s documentary authority while foregrounding emotion. Affect is woven into the image, making it no longer static.

Mohanad Yaqubi’s archival explorations reveal the performativity of colonial images, highlighting what is intentionally omitted or obscured. His film Off Frame AKA Revolution Until Victory (2016), embodies this gesture most clearly. The feature-length documentary essay is built entirely from archival footage produced by the Palestine Film Unit (PFU) and other militant cinema collectives between the late 1960s and early 1980s, a period when image-making was explicitly political but later fragmented, lost, or suppressed. Yaqubi reassembles these remnants from European television vaults, NGO records, and forgotten film cans, allowing the archive to perform itself. Cuts, glitches, and absences remain visible, exposing how colonial and institutional frameworks mediated the visibility of Palestinian resistance. The performativity of the colonial image emerges through this tension. Whereas Western media once framed militants and refugees as objects of humanitarian pity rather than agents of history, Yaqubi reactivates these images so that the camera becomes a site of resistance rather than representation. What was once omitted or obscured—the voices, gestures, and self-representations of the colonized—returns through Yaqubi’s process of re-editing and re-contextualization (Yaqubi, 2016).

Dima Srouji, A Cosmogram of Holy Views, 2025. Installation view, Ab-Anbar Gallery, London. Photo: George Baggaley. Courtesy of the Artist and Ab-Anbar Gallery

In Dima Srouji’s recent exhibition, A Cosmogram of Holy Views, one sees a careful unpacking of these dynamics. Through the juxtaposition of missionary images, personal archives, and contemporary photographic practice, Srouji illuminates the persistent tension between mythologized vision and lived reality. Her work foregrounds Palestinians themselves, their presence, labour, and rituals, while destabilizing the Western gaze. Sacred objects are inverted, their overlooked aspects brought forward while conventional icons recede. In dominant visual traditions, Palestine’s people and land are rendered as background scenery to a mythologized conception of the Holy Land. Here, that hierarchy is quietly but powerfully reversed, and Palestinians are foregrounded (Srouji, 2025).

To unbiblify is to intervene in this flow, re-anchoring images in relational and ethical frameworks, allowing audiences to witness the ordinary textures of life rather than only the spectacular or the mythic. It is an invitation to see beyond the iconic, to dwell in the margins, and to honour the habitual rhythms of the land.

Toward a Habitual Sacred

To revisit these images today—historical, archival, and contemporary—is to confront multiple temporalities: the gaze of missionary projection, the habitual and the foreseeable. These layers coexist, sometimes always in tension, revealing the land’s persistence beyond imposed narratives. Unbiblifying is not about erasure; it is about recognizing the sacred not as revelation but as habit, not as myth but as presence.

As Ariella Azoulay (2008) reminds us, “every photograph contains the potential of a different gaze.” To cultivate this potential requires humility, patience, and attention to detail. It is an ethical practice: letting absence speak, letting margins guide, and letting the habitual assert itself.