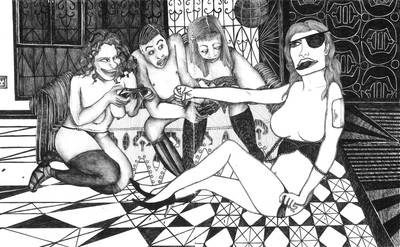

Drawing by Vidha Saumya

Elham Rahmati (b. 1989, Tehran) is a visual artist and curator based in Helsinki. She is the co-founder and co-editor of NO NIIN. In 2019 and 2020, she worked as the curator and producer of the Academy of Moving People & Images (AMPI), a film school in Helsinki for mobile people.

Vidha Saumya (b. 1984, Patna) is a Helsinki-based artist-poet. She is the co-founder and co-editor of NO NIIN – an online monthly magazine in Finland, and a founding member of the Museum of Impossible Forms – an award-winning cultural para-institution in Kontula, Finland.

Good and bad, I define these terms

Quite clear, no doubt, somehow1

Elham Rahmati

“Solidarity does not assume that our struggles are the same struggles, or that our pain is the same pain, or that our hope is for the same future. Solidarity involves commitment, and work, as well as the recognition that even if we do not have the same feelings, or the same lives, or the same bodies, we do live on common ground.” — Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion2

This summer, instead of staying in Helsinki and enjoying that one month of the year where it’s possible to wear sundresses, float around the city and smile at strangers without freaking them out, I decided to travel to Iran. I was overwhelmed by how much I missed my family, friends, and good food, so the minute I received my first dose of vaccine, I hopped on a plane and left. It was only a week or two after my arrival that a looming rumor started spreading around about Iran’s parliament debating whether to restrict the use of international social media platforms and instant messaging services, a legislation that threatened to plunge the country into cyber-darkness. Journalists, political and online activists, and ordinary citizens were all concerned that the restrictions would devastate Iran’s fragile civil society and eliminate the already limited online rights and liberties that remain open to the public.

To self-isolate an already isolated country is beyond any common-good-serving logic. What do I mean by an isolated country? How about a quick history lesson here?

Despite invasions by the Greeks, Arabs, and a variety of Turko-Mongol armies and enduring massive losses and casualties, Iran has somehow managed to keep its own language and culture while also carving out its own distinct niche within Islam by accepting Shiism. According to Shirin Hunter3: “Iran has also paid a price: loneliness. In its neighborhood Iran has no natural allies or ethnic kin. Those who are closest, like Afghanistan and Tajikistan, are separated by religion while those who are close by religion like Iraq and Azerbaijan are separated by ethnicity and language. This loneliness also means that one can mistreat Iran without having to face opposition from other states.”4 Add to this, the decades long, torturous political and economic sanctions imposed on Iran by the US and its countless allies, sanctions that have negatively impacted the country and its people’s livelihood in every possible aspect.

I have often thought about how this situation, geopolitical and otherwise, has affected us in terms of our understanding of solidarity with people of other nations/races/ethnicities/religions and their social/political/economic struggles. What does solidarity mean to us? Who do we choose to extend or not extend it to and who do we wish to receive it from? This is a complex question on many levels and I don’t have an oversimplified answer for it. All I have are observations which will not amount to any solid answer. I have tried to approach it on a personal level though–as one does on NO NIIN.

For the generation of my parents–those currently in their 60s and 70s–history is divided into before and after the Iranian Revolution in 1979. If you ask the same question of us millennials, I reckon many would recall the Iranian Green Movement in 2009 as their personal turning point. The Green Movement protests were a significant event in modern Iranian political history, possibly the largest since the Iranian Revolution of 79. Protests by the Green Movement erupted following the 2009 Iranian presidential election, with protestors demanding that Mahmoud Ahmadinejad be removed from power.

In 2009, I was 20 years old and studying in a painting BA program in Isfahan. I was and still am very interested in politics, with the exception that back then, I was clueless about what was going on. What narratives are at work, and to whose agendas am I contributing? I have a memory of myself on Quds Day, which is celebrated in Iran as a day to condemn Israel. That year, the protestors were hoping to use it as an opportunity to vent their anger under the legal guise of an official rally, so we took to the streets with our green wristbands and victory signs, blending with the crowd and chanting our own slogans. There was a popular slogan that was birthed that day and one that I mindlessly ended up repeating after: “No Gaza. No Lebanon. I give my life for Iran.” People were tired of the neverending economic problems, and there was and still is a popular belief that all our money is being spent in Gaza and Lebanon and that we’ll be better off if Iran stops its “meddling” in the affairs of the region. Meanwhile, we were also chanting slogans like: “Obama, Obama — either with us, or with them!”. Apparently, we thought it was fine for the US to intervene in our affairs. I have to add that there were more progressive voices within the Green Movement that denounced these slogans, but sadly I couldn’t hear them. The movement didn’t last more than a year, it was quite brutally suppressed, and our “leaders” were put under house arrest, where they still are. So we had no choice but to accept a temporary defeat and go back home. The Arab Spring followed a year later. I distinctly recall the night that Hosni Mubarak stepped down during the Egyptian Revolution of 2011. I remember it because I didn’t sleep the entire night, not because of the joy I was feeling for the Egyptian protestors, not at all that, but out of sheer jealousy. At that moment, in Tahrir Square, they were living our dreams. I couldn’t feel joy because it hadn’t occurred to me yet that we in Iran are not the center of the universe and that it’s ok if this is not our moment. I couldn’t feel joy because that joy is born out of sharing solidarity and empathy with others, and if no one has ever taught you what that looks like or feels like, then it won’t come to you that easily. Losing this notion of solidarity is a byproduct of surviving within oppressive authoritarian, imperialist, capitalist, or neoliberal systems as they do a great job of turning every single aspect of our being into a competition and alienating us from one another.

I did eventually move on from that self-absorbed and overly sentimentalized image of resistance that was carved in my head by less than intelligent opposition groups and diaspora stunt activists whose limited imagination couldn’t allow them to envision a world in which we are not alone in our struggle and one does not have to be indifferent or belittling towards other people’s struggles or pit them against each other, in order to be heard. I’ve learned that if one has truly understood devastation caused by oppression of any kind, they will see it, recognize it, be unsettled and enraged by it and speak up against it not only when it happens within their own borders but everywhere. To be positioned in isolated geopolitics, that we can’t do much to change, we can, however, stop allowing that isolation to leak into our mindset and our entire understanding of the world. So yes, I stopped chanting that cruel slogan and I don’t plead to Obama–or any other imperialist for that matter–anymore. I know far better these days.

To us, sharing lived experiences is crucial as it contributes in many ways to the arduous–at times hopeless–dream of building communities, reclaiming spaces that bring us together, and within them, sharing tools and ideas on how to resist oppression, whether online or in person. What is of great value to us is our personal journeys in understanding the interconnectedness of our struggles, our common ground and making space for the different roles and capacities with which we afford to partake in a movement or a community. What we all need and deserve is time to get there, patience, guidance and generosity from those who are already there and above all resources, resources, resources.

I started with a quote from Sara Ahmed and will end with a quote from Mir-Hossein Mousavi, the leader of the Green Movement, in his statement published on Quds Day in 2009:

“Our victory is not something in which one is left worse off. Even if some of us are slow to recognize the good news, we must all succeed together.” — Mir-Hossein Mousavi, Statement No.13

”پیروزی ما آن چیزی نیست که در آن کسی شکست بخورد. همه باید با هم کامیاب شویم، اگرچه برخی مژده این کامیابی را دیرتر درک کنند.“5 — میرحسین موسوی

Between comfort and catastrophe

Vidha Saumya

Whenever I want to find a new recipe, I prefix my YouTube search with ‘Easy and Quick’. Something in my mind says: making it once isn’t going to turn me into an expert, so why bear the burden of being full-too-authentic and processual about it? Delightfully, these searches lead me to accounts of people whose videos are a nuanced blend of food preparation, video production, instructions and audio tracks. The hosts’ voices are endearing and inviting, the kitchen is not located in a set, and the cooks are methodical and calm. I do get enamoured by overnight oats and chia pudding recipes, they don’t seem to stick around – anything formulaic although designed to make jobs easier are difficult bargains for me.

On the other hand, catastrophising something small comes ‘Easy and Quick’ to me, too.

Last week I was to attend a friend’s wedding and had long decided that I would wear a saree. A week before the wedding another friend who was also going to attend the wedding sent me photos of three dress options for herself. Without a second thought, I assumed the dress code for the wedding was a Western dress and I had somehow not received this information. Before I could properly consider what I had been asked for an opinion on, my mind raced through thoughts of what possible dress I could buy, how much that would cost and so on. I even looked up how to wrap a saree like a dress.

The relationship between comfort and catastrophes can be understood as a relationship between the known and the unknown. Our mind catastrophizes to grapple with the unknown while we undermine the known to be dull and repetitious – like daal-chaval-aloo ka bharta, which happens to be my favourite meal. The phrase is also used as a shorthand for ‘predictable boredom’ in India.

Both catastrophe, and ‘comfortable’ routine, bring impatience. While our catastrophic impatience stems in part from repeated accounts of our trust being mishandled, it also stems from a desire for some form of express speed justice – so that we can do what we can and move on to what we want to do. However, this approach usually leaves little room for dialogue and understanding of each other’s points of view. What is further demotivating is that the big players, those who truly need to be questioned on their working methods are frequently let off the hook, either because we assume they have a lot of power or because it’s exhausting to engage with someone who has much more resources to spare than you. This is why newer, smaller entities end up becoming overly cautious, self-censoring and politically correct – resulting in taking themselves so seriously that will put the seriousness of melting glaciers to halt.

Sometimes our imagination of loading someone with the task of making all wrongs right is shaped by our frustration but also emanates from a sense of hope. For example, when a non-male member is appointed to a powerful position in an organization, the newly appointed must handle all issues of discrimination, hierarchies, and care work flawlessly – at once. The pressure builds. For many people in high-pressure positions, it is inconceivable that they are allowed to take time, to ask for help or to feel that they can bask in the enjoyment of having left the box of an imposed identity unticked.

Growing up (in India) a hearty wholesome meal of lentils, rice and mashed potatoes – daal-chaval-aloo ka bharta – used to be the staple home-meal after any kind of longish time away from home or even after a rough day. Daal rice, in my opinion, is best cooked in a pressure cooker. When I moved to Helsinki, I brought with me a pressure cooker. This stainless steel vessel in my opinion is the fastest and safest way to cook daal-chaval. Sealing the steam in a pot, causing a safe, controlled rise in pressure that raises the boiling point of water and thus the cooking temperature also rises. It cooks faster and better – slow cooking, like slow travel, is a matter of debate and often requires a well-salaried job. The poet Kabir said, “Maali seenche sau ghada, Ritu aaye phal hoye”, a great metaphor for all those people who seek the fruits of the action immediately. But the poet’s fruit metaphor did not anticipate that the world is impatient and wants fruits fast. Sometimes I wonder if we put ourselves under this kind of pressure in order to save time and provide solutions faster.

A pressure cooker whistles, when after heating the contents on the stove with the lid and pressure regulator in place, it has reached the full operating pressure to cook the food. It’s then you need to reduce the heat and fine-tune the rest of the cooking time. Even a pressure cooker, the symbol of fast cooking, can’t be rushed after a point, it has to be slowed down.

Kamla Bhasin, one of my dearest feminists, teaches us how to whistle very seriously. It’s an activity of leisure and thrill that we all must master. When life jolts you to think catastrophically into a fight or flight mode, while it away in slowed downtime, creating comfort.