Ingrid Fadnes is a Norwegian journalist, currently working at the feature department in the newspaper Klassekampen. Fadnes has lived in Latin America for more than a decade and has followed political occurrences especially surrounding the conflicts between agriculture and indigenous peoples. She has made several radio documentaries from Latin America, as well as the Sápmi region. Between 2015 and 2018 she spent time in the state of Bahia in Brazil investigating and documenting the substitution of natural forest by eucalyptus plantations designated for paper production. As part of this work, she made the documentary film MATA.

I am standing in between rows of eucalyptus trees. I cannot hear anything. Not a single sound. The silence resembles a winter-dressed and dark Norwegian wood. It is the deepest and most soothing silence I have ever experienced. We have a children’s song in Norway describing this, a Christmas song, where a stanza goes like this: “all the sounds are wrapped in cotton wool”. Though, what I am standing in is not a winter forest. It is warm. The temperature must be around 27 degrees Celsius and it is in the light of day. The absence of sound is not soothing at all. There is something unnatural about this apparent forest.

My eyes go from the dry ground and up, following a trunk, about thirty meters to the top where I can see the green crown of the trees. All the branches below the crown have lost their leaves. I grab one of the dry and naked branches, and it snaps off almost without any effort on my part. It is like it has drily rotted, from the inside out. I take a step forward and I hear the ground.

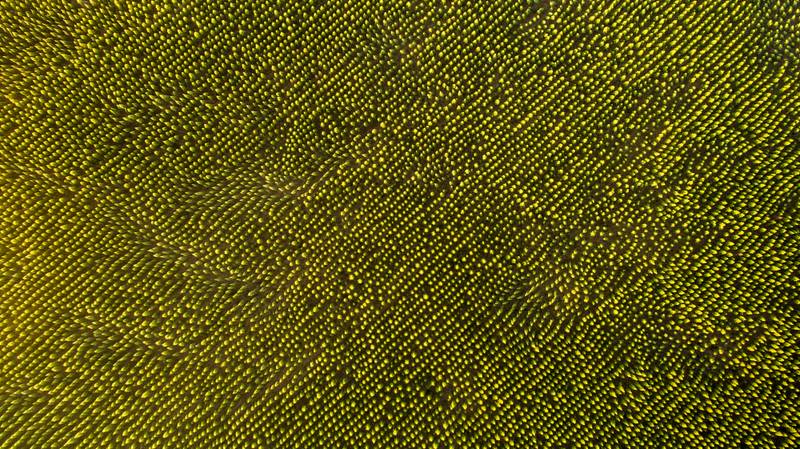

Dry leaves. Dead branches. This is the only sound I can hear in this “forest”. No birds. Not even insects. We want to see this silent area from above. What does it look like? How big is it? The continuous unvaried humming from the carbon fiber propellers of a small drone breaks the silence as it leaves the ground. The drone will be our eyes in the sky. It goes slowly upwards as we fix our eyes on a small screen. For every meter, the drone ascends, the visible area of rows of planted eucalyptus trees increases. When we have reached 500 meters above ground, the maximum reach of the drone we are using, the camera is still not able to capture the entire area. It is too big, it is continuous, it seems endless, like the ocean.

With the view from above, we can see that it is moving. Slowly, in circles, some of the trees bend a bit forward, and then back again, looking like waves, sometimes moving in the same direction, other times brushing against each other. They make patterns, constantly changing. Is it choreography? Yes, they are dancing. That is my first thought. It is beautiful to watch. Eucalyptus is famous for its aesthetics. It is an elegant, sophisticated tree, with oval-shaped leaves. But by looking again the movement appears more stressful. Are they anxious? Are they uncomfortable, suffering, trying to escape? Do they communicate with each other, are they trying to send us a message? All these thoughts flow through my head while observing the trees from the perspective of a bird.

The humming sound of the drone increases as it descends. We let it hover in the air a few meters above the ground, among the trunks, before we let it move forward, slowly, revealing a systematic plantation of rows and rows of the same tree. Same size, planted with an exact distance from one another. I wonder if their roots can touch underneath the ground. They might be intertwined, growing together without us being able to see it. I come to think that maybe they use their flexibility to move with the wind and at least touch each other with their crowns; giving each other some kind of comfort, a small touch of care. “Hang in there”, they might say while bending towards the other, and “maybe they will forget about us, and let us grow old and have other species around us”. Being forgotten will be the only way to live. A eucalyptus tree can live for at least 250 years in the wild. The ocean of eucalyptus trees I am looking at has a life cycle of seven years, maximum. They are only kids.

This is not the wild. This view, this absence of sound, and beautiful but unnerving choreography are from a region called the Extremo Sul in the state of Bahia on the Eastern coast of Brazil. This is the same place where the Portuguese colonizers first reached land, naming it Costa do Descobrimento (Coast of Discovery). This marked the beginning of colonization and what the Indigenous peoples of the continent called the ‘500 year long night’. It is also the beginning of the end for the natural forest – the Mata atlântica, that once stood here, and where I now look at rows of silent trees. I am sure that they do want to tell us something.

After my first meeting with the silent “forest”, together with the Brazilian photographer Fabio Nascimento, looking at it from the inside, from above, and trying to record its silence, we realized we needed to come back and try and find its story. Between December 2015 and December 2018 we visited the region several times, trying to observe a landscape that has changed over time with a noticeable escalation in the last four decades. In our visits during a few years, we could see and hear how the accelerating rhythm of capitalist productivity constantly changed the landscape. Both Fabio and I have been to several places and documented people and nature, but what we could see and document in this particular region is perhaps one of the most profound examples when it comes to mankind’s destructive use and abuse of nature.

Observing and becoming aware of the consequences of landscape changes is often difficult unless you spend time in a place. We spent only a few years there. The ones who often will hold specific, accurate, and deep knowledge of how their surroundings have changed are those people who live in a region throughout their lives, and generations: They can tell you how humidity has changed, if it rains more or less, they can imitate the sound of a bird that they no longer hear, they can tell us what once was here and what we no longer can see. This reminds me of the words of a Sámi reindeer herder from Sápmi, the Indigenous territories in the northern part of Scandinavia and Russia. The reindeer herder was fighting against wind turbines on their pastoral land. She looked at the mountain where the planned turbines were to be constructed and she said: “If we lose something we need to know what is lost”.

Knowing what is lost was something we also heard from the people in Extremo Sul da Bahia. We heard it in the rapidly growing, almost improvised cities in this region, we heard it from the Indigenous people Pataxó, the Pataxó Hã-Hã-Hãe, and the Tupinamba. We heard it from the fishermen – and women, we heard it from people living in lonesome and small houses on the narrow strip of vacant land between the walls of plantations and the highways, we heard it from the quilombolas – the villages where the descendants of African-Brazilian slaves live. We heard it from the workers who transport timber during the day, during the night, a never-ending working routine. We heard it from the small-scale farmers, and the farmers with no land, the thousands occupying areas to get a plot where they can plant food crops. They all have stories of what once was there: “Over there we had a lake, but now it is dry”, “Our well was full of water before, now we have to dig deep to find a drop”, “There used to be a lot of fish in this river, now we have to go far out to the sea to find sufficient hauls”, “I remember the forest when it had thick trees,” I remember… It used to be… What they tell is based on lifelong experience and observations, but their knowledge is often reduced to myths.

The myth

A myth can be understood as a sacred story, a narration of sacred history. In the understanding of Mircea Eliade (1971), every myth shows how reality came into existence, and explaining how things came to be is also indirectly answering another question: Why did they come into existence?

However when people’s knowledge about nature is described and reduced to “myth” the “myth” is understood as a narration without a historical basis, a superficial and superstitial knowledge.

The world is full of myths, narrations on how reality came into existence, and why it came into existence. The many creation myths all describe the earliest beginnings of the present world – how we came to be. In Mesoamerican creation myths, the Gods created human beings from maize. In Norse or Scandinavian mythology, the world arose between light and darkness, between fire and ice; in the vast void of Ginnungagap – all life was set to begin. According to Christian belief, God created the world and the universe in seven days; on the first day, the light was created, and by the seventh day, God finished his work of creation and rested. Whether we choose to believe it was created in seven days, out of crop plants, in between light and darkness, fire and frost, or with the modern scientific Big Bang, the world came to be with diversity in species and colors. This we know. How do we today, in our present time, - create those opposite “myths” of the creation: those myths about how we slowly demolish what once was created. What would be our myths of destruction?

The history

In 2012 the United Nations created The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). The role of IPBES is to provide the state of knowledge regarding the planet’s biodiversity, ecosystems, and the contributions they make to people. The very creation of IPBES is due to human destruction. We need to understand more of our actions. What is lost? Seven years after the creation of IPBES, in 2019, they published the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. The report claims that nature is declining globally at rates unprecedented in human history – and the rate of species extinctions is accelerating. Numbers and figures from almost the entire planet give us small drops of what has become an overwhelming and almost uncontrollable development, the destruction of something that we once had. The reports have gathered and systematized information that people connected to their land have held for generations – they already knew what we have destroyed, but do we believe in their “myth”?

In the last 75 years, the world has lost more than half of its rainforests. In Finland, the Landscape Rewilding programme tells us that 1.7 million hectares of biological peatlands have been lost, along with more than 90 percent of old forests below the Arctic circle. In mid-September this year, huge fires in California were close to making ash off some of the world’s largest trees, the Sequoiadendron giganteum - giant sequoia – one of the oldest living organisms on Earth. In the 2020 year fires in California, we lost several thousand of them. In Norway (as in many countries), if you want to observe and enjoy thick and old trees you must go to the cemeteries. It feels strange but almost prophetic, that where we bury our dead ancestors, we let the trees we have killed in the wild, live and grow old - in peace.

In the Extremo Sul da Bahia in Brazil, only 4 percent of the original Mata atlântica remain “intact”. When we observed it from a bird’s perspective, with the help of our humming drone, it looked like small islands in the landscape, surrounded by eucalyptus. The Mata atlântica originally held an incredible amount of biodiversity. Eucalyptus plantations are the extreme opposite, being a complete homogeneity.

The eucalyptus is an introduced species in Brazil. It is originally from Australia. There have been 800 species of eucalyptus registered so far, though there is no need for several hundred species for the industrial production of eucalyptus, primarily for cellulose for papermaking. The cellulose and paper-producing companies need only a few that they can manipulate and force to grow at a rapid pace, meeting “the needs” of the international market. In Brazil, the cycle of one eucalyptus tree, from being a small sapling to becoming a thirty-meter tall tree is about seven years. On April 9 2015, one of the world’s leading cellulose companies, the Brazilian ‘Suzano’, attained official permission from the Brazilian National Technical Commission on Biosafety to use a genetically modified variant of the eucalyptus called “Evento H421”. This modified innovation can shoot from the ground and thirty meters into the air at record speed. Imagine now standing in front of a silent wall of 30-meter high eucalyptus trees, with nothing but dry and dead leaves in between, and then – all of the sudden - it is gone. A huge area of the landscape will open up around you. And all of a sudden it is there again. What does this rhythm do with the trees, the soil, the people around it?

The story of how eucalyptus plantations started in Brazil does not go so many years back. It was in the 1960s and 1970s, while Brazil was under the control of a brutal military dictatorship, that the state-run bank BNDES financed plantation projects. Natural forests have increasingly been replaced by plantation “forests” and what happened in Brazil was part of the desired policy. In the 1970s, The Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO) gave the tree plantations official recognition as forest. Planting trees was, and still is, part of a narrative of reforestation.

One of the first companies in Brazil, ‘Aracruz Cellulose’, run by the Norwegian businessman Erling Lorentzen, started tearing down what was still left of the Mata atlântica with the help of huge chains, tractors and local inhabitants – in need of paid work. In 1972, Lorentzen established Aracruz Cellulose, and in 1978 the first factory was opened. From this moment on the eucalyptus plantations began to spread in a steady but unstoppable motion. By the time of our visits, the number of companies, factories and harbors had increased considerably. Together with Aracruz Cellulose and Suzano, the companies Fibria and Veracel operated in the region. Veracel came to the region in 1998 as a joint venture with Fibria and the Finnish-Swedish company Stora Enso. One of the goals of Finnish forest policy (according to themselves) is that “forestry should aim at structural features similar to natural forests”1, and that “when attention is paid to the economic profitability and social sustainability of forestry, the natural cycles will be altered as little as possible”2. Norway’s oil fund, or the Government Pension Fund Global in its official name, has invested in all of these companies. On their homepage, there is a continuous update of the continuous flow of money that trickles into the Norwegian people’s collective account. It is as if the water that disappears from the two main rivers in the Extreme South of Bahia, río Jequitionha and río Mucuri, flows into the account in the form of numbers.

When people in Bahia started to protest, claiming that the eucalyptus emptied their lakes and rivers, and later that the pesticides used continuously in the plantations harmed the soil and the people’s health, it was rejected as a myth. In our work in Bahia, and in what later became the documentary MATA, we talked to one of the most important researchers on forest resources and forest engineering with a focus on the hydrographic basin, Walter de Paula Lima. He is a researcher at the Escola Superior de Agricultura Luiz de Queiroz (ESALQ) in Brazil, a school where they had courses on how to deforest wetland areas and tropical forests when he was a young student in the 1960s. Later on, he became deeply involved with the expansion of forest plantations in Brazil, especially eucalyptus. He wanted to prove through his research that people’s assertion that eucalyptus dries the soil was merely a myth. Those were the words he used. A myth. However, at the same time, he observed how the model of eucalyptus plantations, with an extremely short rotation, expanded, not only in Brazil but in several countries in South America, and decided to research their effects on streamflow. What did he find? After six years of observing a eucalyptus plantation, measuring the rain and the flow of the stream, he concluded a statement he shared with us in the documentary film MATA: “The people were right. It went from being a myth to becoming a truth”. The river dried up. Due to how the eucalyptus was planted.

Walter de Paula Lima underlined in our interview how it is now up to the companies to deal with this truth. They created the silent “forest”. How they will deal with the myth that became the truth will condition our future.

The absence of sound was what shouted loudest to us during the first visit to this region in Brazil, and was what convinced us to stay and listen. The silent “forest” has a lot to tell. Both on how it came to be, and why. How the future unfolds depends upon how the “myth”, the narration of how it came to be, is understood – and believed.