Poster for the short film ‘Heaven Reaches Down to Earth’

Sharron L. Todd is a writer, filmmaker and creative professional. She has lived in Helsinki for ten years via Brooklyn, New York and other parts of the world. During her time as a co-owner/operator of Finland-based Brooklyn Café and Brooklyn Baking Co, she has published articles on social topics and both edited and wrote for an award-winning grassroots book No Justice, No Peace. She wrote and directed her first short film, Dear Elijah, released in 2020. Prior to her life in Finland, Sharron wrote screenplays, poetry and essays for over 20 years.

A review of African Express Short Films screening at the 34th Helsinki International Film Festival.

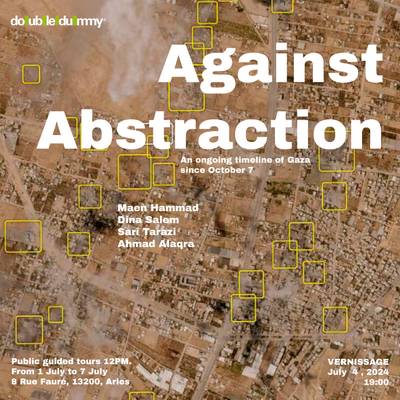

African cinema played a major role at the 34th Helsinki International Film Festival – Love & Anarchy (HIFF). As one of the central themes of HIFF this year, a diverse selection of African films took Finnish audiences across the culturally rich continent and into the vast imaginations of African filmmakers. HIFF partnered with Helsinki-based organizations Think Africa and Ubuntu Film Club, the embassies of Morocco and Tunisia and the National Audiovisual Institute, to choose a selection of films labeled as the African Express program.

The African Express selections showcased 11 feature-length films from various countries, such as the 1966 film, Black Girl, directed by Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembène and Tunisian director Sonia Chamkhi’s 2015 film, Narcissus. These eclectic selections were further complimented by the five extraordinary short films chosen for the African Express – Short Station. Each of these short films was able to deliver a wealth of human experiences in under 30 minutes of cinematic splendor.

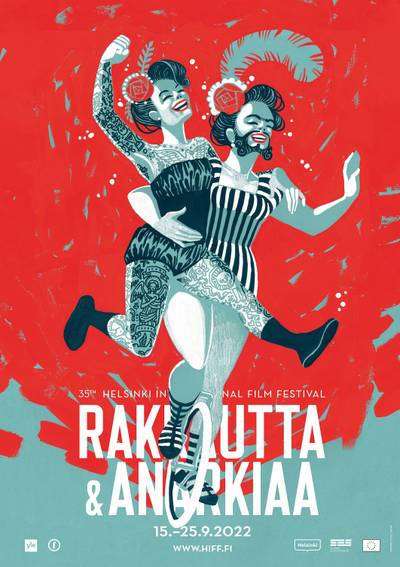

Poster for the short film ‘So What If The Goat Dies’

The short film program opened with French-Moroccan director Sofia Alaoui’s cinematographic feast, So What If The Goat Dies (winner of the Short Film Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival 2020). Abdellah, played by Fouad Oughaou, is both an obedient son and a young, diligent shepherd who lives in the remote mountains with his elderly father. Harsh weather forces him to travel to the nearest village in search of food to save his goats. Abdellah is also a man of unwavering faith. He relies on his religion for guidance and comfort throughout the film, especially when he reaches the village only to find it abruptly deserted by its inhabitants. He soon finds out that the evacuations have been caused by a sudden supernatural phenomenon. Abdellah must contend with the limitations of his faith and the mysterious bright green lights that fill the desert sky.

It is a treat to be able to experience a film made by an African woman that includes subtle elements of science fiction seen in Hollywood blockbusters. Alaoui gives audiences a refreshing new perspective in a space normally reserved for male storytellers. The backdrop of a sprawling Moroccan desert (captured by stunning cinematography) interrupted by streaks of alien lights is enough to want to see this film in feature length. Alaoui introduces a subject that may be more befuddling than an alien invasion: what in fact happens when reality contradicts the purposed confines of one’s faith and religion? This film ends at this question, with the shepherd and his father huddled together in a wooden shed, fearing the unknown and the undoing of everything known to them. So What If The Goats Dies is in desperate need of a lengthier sequel, or even a trilogy, and Alaoui is undoubtedly a gifted filmmaker who would be completely up to the task.

Poster for the short film ‘Troublemaker’

Through her film, Troublemaker, Nigerian writer and director Olive Nwosu confronts internal questions about her country’s history and the inherited problems of a new generation. Nwosu speaks through the main character, Obi. Obi is a young and curious boy who wanders around his small village in boredom. He is constantly scolded by village mothers for his childish pranks and his behavior toward his seemingly mute grandfather. His grandfather, dressed in traditional tribal garb, stays seated on a bench throughout most of the film. He is troubled by the nightmares of past wars, but his grandson cannot identify with him. The film touches on the struggles of Nigeria’s younger generation, many of whom want to live without the burden of being a solution to their inherited pains. The delicate dichotomy between maintaining old and new traditions is brought out through Obi’s strained relationship with his grandfather and other village elders.

Troublemaker brings into question a reality facing not only Nigerian culture, but that of the emerging generation who find it difficult to draw a line between familial duty and personal freedom. In a recent interview with the African in Motion Film Festival, Nwosu says, “Growing up, every Nigerian child is told that they are the leaders of tomorrow. It’s a slogan that’s heard everywhere, and it frustrates me. It feels like a passing of the buck—the next generation will be the ones to solve the problems, as our parents and grandparents did very little. They were in too much pain.” Ironically, Obi plays to the title of the film, and he is seen as a constant nuisance rather than a child in search of his place and freedom. Where the audience may also see his character as a troublemaker, Nwosu sees him as a change agent. She says, “Obi holds no blame in doing what he does. It’s inevitable, even worthwhile. He’s only doing what has been whispered in our ears for so long, and yet has hindered many of our lives.”

In the South African film Heaven Reaches Down to Earth, filmmaker Tebogo Malebogo broaches the subject of queerness versus the traditional expectations and roles of men in some African cultures. The story’s poetic style of narration is consistent with the physical landscape of the film, which was shot in the stunning Du Toitskloof Mountains and waterfalls in South Africa. Two young men, Tau and Tumelo, hike cascading mountains with their camping gear in tow and little to say to each other. They camp for the night on top of a mountain and come to a realization about their sexuality. They woke up the next morning knowing that their friendship would change forever.

There’s a feeling that this film has been done before. Some could even compare the premise to the critically acclaimed 2005 film Brokeback Mountain, starring leading white male Hollywood actors. However, the difference here is clear. For one, Malebogo had to exercise undoubted boldness to make this film. He bravely raises the topic of sexuality, a subject considered extremely taboo among many African cultures and even illegal in some. Audiences have only in recent years been able to hear the stories of queer black characters (most notably in the 2016 film Moonlight and the 2018 Kenyan film Rafiki). Heaven Reaches Down To Earth is a story that must be told, and it does, ever so quietly, tell the story of two men forced to live double lives by a society that holds them to opposing cultural standards.

Poster for the short film ‘I Am Afraid To Forget Your Face’

Egyptian filmmaker Sameh Alaa’s I Am Afraid To Forget Your Face, tells a captivating story of a young man, Adam, who is separated from his beloved for months. The film is mostly silent except for the ambient sounds surrounding Adam as he inconspicuously journeys through the busy streets of Cairo to reach his nameless love. Adam, seamlessly played by Seif Hemeda, shows he will let nothing stop him from reaching his destination.

Alaa shows his skills as a master storyteller in I Am Afraid To Forget Your Face. He is the first Egyptian director to have a short film screened at the Cannes Film Festival and to also win the coveted Palme d’Or. There is no surprise as to why his film is being well-received. Alaa has a classic filmmaking talent, one that tells a story through motion and picture, rather than words. His ability to tell a love story and a much bigger story of domestic repression without using dialogue, is truly impressive. The film has no voids. Not only is it beautifully shot, it is written in such a way that we are able to meticulously follow the main character through his visible strife and the natural buildup of suspense to his final destination.

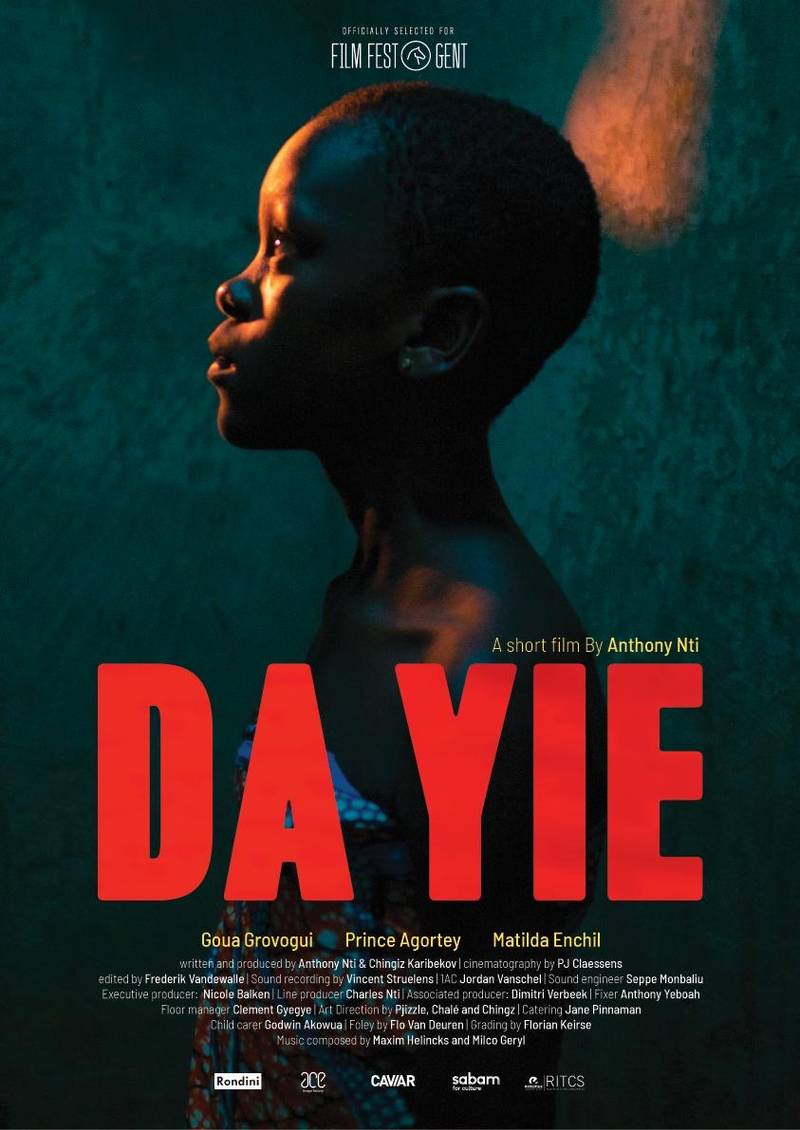

Poster for the short film ‘Good Night’

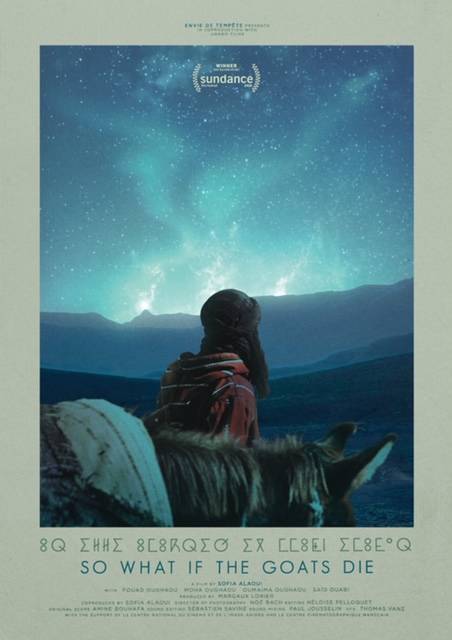

The last of the short film selections takes us to Accra, Ghana, with Anthony Nti’s Good Night (Da Yie). This powerful semi-autobiographical film follows the daily lives of two children, Matilda and Prince. Matilda and Prince, played by breakthrough child actors of the same names as their characters, are close neighborhood friends. The two impressionable children meet Bogah, an adult with knavish intentions. Bogah lures the children into a joy ride with him and impresses them with hard-to-get meals and a day at the beach. At times, Prince seems hesitant about Bogah, but the whimsical and imaginative Matilda convinces him to seize the day. Bogah’s guilt in the end is brought on by Matilda’s infectious personality and the day spent with the children.

Good Night is not a film that is relevant only to African experiences. It is a real story of the human condition, one that has the impossible task of pinpointing the very moment innocence is lost. Though the film focuses on the idiosyncrasies of a child’s naivety and innocent ways, it also shows us that Bogah is an adult who perhaps never had the opportunity to be a child himself. It is in this unexpected juxtaposition that we experience the true beauty of this film.

HIFF’s collaborative selection of African short films for this year’s festival is a hopeful preview of the expansion of diverse stories told in the movie-making sphere. Since its inception in the late 19th century, film has been governed by those who had the means to possess the camera and the platform to reach audiences. Until recently, the world has been heavily influenced by the cyclical images of certain lead characters and storylines- leaving out a breadth of experiences and stories lived by the majority of the world. The time has finally come where stories about Africa, in Africa, about African people – are told by Africans.

HIFF’s move to make African cinema a central theme of this year’s film selections is a sign of progress in tackling issues surrounding diversity and inclusion in Finland. It creates a benchmark for other Finnish film festivals to follow and to make room where there is already space. A lack of space for non-white filmmakers in the Finnish and global film industry was never the real issue. There has always been space for people to tell their own stories; it has only been a matter of the “gatekeepers” relinquishing their keys.

Film is more than art. Film and other sources of media help to shape the imagination of its audiences- feeding them images of people, perspectives on their lives and the nuisances that make us all individuals. It is with this in mind that we see the elevated impact of African films shown at HIFF. The short films in the African Express – Short Station told stories that are not only relevant to African people but to others across the world. Humankind versus religion is not only an African story. Obligation to family and to self is not only a black person’s issue. Domestic repression is a problem in western culture too. Sexuality is a sensitive off-limit topic in many communities. And finally, the loss of innocence is the reason we are all here now. It is these commonalities in being human that will bring about true progress and a better understanding of each other. In the words of filmmaker Nia DaCosta, “I just want to tell good stories in ways that will shine light on lives rarely seen on screen, because stories can push humanity forward.”