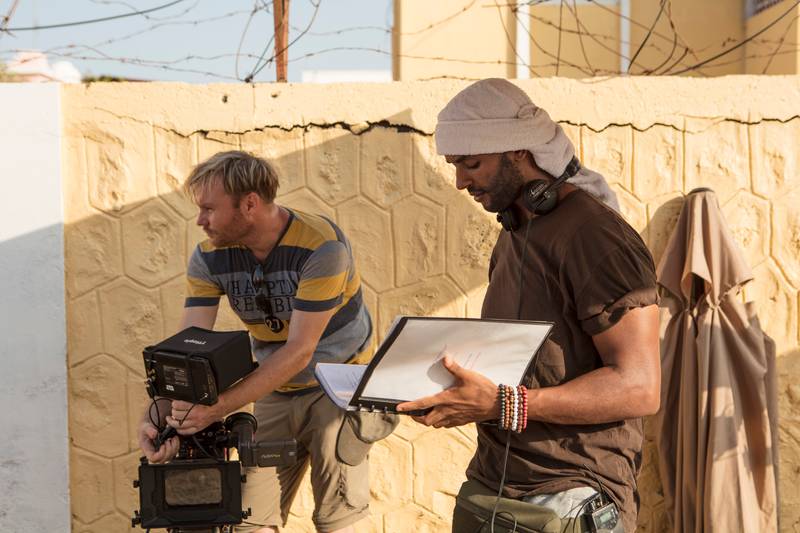

Photo courtesy of The Helsinki International Film Festival – Love & Anarchy, Photography by Mari Mur

Sharron L. Todd is a writer, filmmaker and creative professional. She has lived in Helsinki for ten years via Brooklyn, New York and other parts of the world. During her time as a co-owner/operator of Finland-based Brooklyn Café and Brooklyn Baking Co, she has published articles on social topics and both edited and wrote for an award-winning grassroots book No Justice, No Peace. She wrote and directed her first short film, Dear Elijah, released in 2020. Prior to her life in Finland, Sharron wrote screenplays, poetry and essays for over 20 years.

The first time Khadar Ahmed’s mother had ever seen a Somalian film was when she saw her son’s first feature, Guled & Nasra (internationally known as The Gravedigger’s Wife). She could never guess that her love would lead to her son’s greatest accomplishment to date. Guled & Nasra hit the international film community like a storm, and it is just getting started. The film has already won many prestigious awards, including Africa’s most coveted prize, FESPACO’s Golden Stallion of Yennenga. It is also the first Somali film to ever be submitted to the Academy Awards for Best International Feature Film.

Guled & Nasra was released in theaters on November 12, 2021. Before that, it had been an official selection at many international film festivals (with 12 nominations, 13 wins and counting). Khadar’s mother was his date to the 2021 Cannes Film Festival. She stood next to her son as his film competed with renowned Chadian director Mahamat-Saleh Haroun’s Lingui. Haroun is one of Khadar’s favorite African filmmakers. His mother watched on as her son’s film was being judged by Cannes’ jury member and Mauritanian-Malian filmmaker Abderrahmane Sissako, another one of Khadar’s film heroes. Khadar reminisced, "I remember watching Haroun’s film A Screaming Man in 2010 and I remember leaving the cinema crying and overwhelmed by the impact the film had on me. I felt the same way when I saw Sissako’s Oscar-nominated Timbuktu. These were the two African pioneers that I deeply admired. I could not believe my film was in competition with Haroun’s film and that Sissako was a jury member judging my film. Being in the company of Haroun and Sissako, who said so many beautiful things about Guled & Nasra, my very first feature, was more important to me than winning an award and something I could never imagine. It brought me to tears.

During the Somali Civil War that began in 1991, Khadar’s mother shielded her children with laughter. “As the war happened around us, with the sounds of bombs and gunfire shaking our home, my mom would gather us together and tell us stories to make us laugh, she made us forget about the madness and craziness around us”, Khadar said. “She taught us that even in difficult moments, we must remember to love, to enjoy, and to dance, because we never know when our final moment will be.” This exemplary display of resilience clearly shaped Khadar as a person, but it also had an undoubted impact on his creativity as a filmmaker.

Khadar attributes the strength and love of the women in Guled & Nasra to his mother and other women in his life. “I was raised by a very strong Somali woman and have been surrounded by very strong African women. They do everything to make sure that their families are healthy and strong.” He laughs, “The men think they are in charge, but they are not. They may be the head of the family, but the woman is the heart.”

Photo courtesy of The Helsinki International Film Festival – Love & Anarchy

In the film, Nasra, who is beautifully played by Canadian-Somali actress Yasmin Warsame, is in need of a kidney transplant. Even though she is gravely ill, she does not want this to define her family’s life. Her husband, Guled (in a stunning performance played by first-time Finnish-Somali actor Omar Abdi), is a gravedigger who desperately searches for odd-end jobs to pay for her surgery. He is heartbroken because of her illness, but even in her frailness, Nasra comforts him and reminds him to find the beauty around their circumstances. In one ethereal scene, she builds up enough strength to leave her sick bed and convinces Guled to crash a stranger’s wedding with her. After they bargain their way in, they dance close together the rest of the night, against a backdrop of swinging fairy lights and the laughter-filled celebration of the strangers next to them. Khadar explains, “I really wanted to show these small moments. We understand why Guled is in love with Nasra; she deserves it. She tries to temporarily forget the bad moment they are experiencing by shining a light on the good happening at the same time. I think this is real life. In one day, we go through so many different emotions. In one, we are laughing; in another, we may cry. I want to show all these moments, not just the bad ones.”

There is no question that Khadar’s upbringing had a major influence on his film. This is what makes it surprising that the first important person he said “No” to was his mother. Khadar and his family immigrated to Finland in the late 90’s to escape the Somali Civil War. Khadar found himself in a place where no one looked like him or his family. “It was the first time I realized I was black. It had never occurred to me before, because in Somalia, everyone looks like me. There is no one to compare my blackness to. But here in Finland, where the majority is white, I realized how different I was from everyone.”

At this point, Khadar felt something he had not experienced before. He had an overwhelming need for representation to combat his new identity, one of isolation and as a sometimes unwelcome stranger in his new home country. Khadar sought refuge in watching films.

My mom said three things: you are black, there is absolutely no representation here. You are Muslim. There is absolutely no representation here. You are a refugee; there is absolutely no representation here.

Khadar’s family immigrated to Finland in 1997. At that time, there was very little available to draw from in Finnish television programming, and online films were not yet developed. He frequented video stores in search of movies with stories that had black characters. He rented African American films such as Hurricane and Poetic Justice and anything else he could get his hands on. Khadar knew virtually nothing about the fundamentals of filmmaking at the time and learned more about it from watching movies and also from interviews on the British Broadcasting Channel (BBC). In one interview with Denzel Washington, Khadar only then realized that Denzel was in fact an actor and that he had not just come directly from the Hurricane set for the interview. The first time Khadar learned about the Oscars was in 2002, when Denzel Washington and Halle Berry became the first two African Americans to win an Academy Award in leading roles.

In his search for something familiar, Khadar found his calling. He wanted to make films. When he shared his future dreams with his mother, her fears set it off. He said, “My mom said three things: you are black, there is absolutely no representation here. You are Muslim. There is absolutely no representation here. You are a refugee; there is absolutely no representation here.” She was afraid because there were no known examples of successful black Muslim refugee filmmakers in Finland. She did not believe he would get the support he needed. She had witnessed the ill treatment of other African refugees and did not want her son to suffer. She told him to study instead and seek another profession. Khadar said, “No.”

Instead, Khadar chose to rely on the counsel his mother had given him out of love, and not the one she gave out of fear. He remembered to “enjoy and dance” even in the difficult moments, and those moments did in fact come. He applied to film school many times, but he was never accepted. He tried to get one of his first short films publicly funded in Finland, but one of the funders did not believe it would be successful (he later received an apology from that very person when his film was selected for the festival circuit).

I decided to write a story about a person like me, one that was raised by parents who put importance on dignity, love, and compassion. I only know Somalians like me and my family.

Khadar began writing Guled & Nasra ten years ago. He had considered calling it “Black Love.” He wanted to write a story about Somalians he had not yet seen. “I’m so tired of seeing depressing African films about slavery and civil wars; about suffering. And though I wanted to address an issue like the health crisis in Africa, I wanted to tell it through love.” He could not identify with the Somali films that had been made. He said, “You’re making a film about me, as a Somali, and I cannot relate whatsoever. There are mostly films out there about Somalians being pirates, warlords, or us either showing cruelty or being victims of it. I cannot relate to these characters who were meant to represent me, my friends, and family.”

Khadar was frustrated by the misrepresentation of everyday Somalis like him and his family. He agrees with the idea that the global image of black people is negatively affected by one-dimensional caricatures meant to represent real people and is further harmed by unrealistic depictions of black culture in film. He says, “I decided to write a story about a person like me, one that was raised by parents who put importance on dignity, love, and compassion. I only know Somalians like me and my family.”

Photo courtesy of The Helsinki International Film Festival – Love & Anarchy

When deciding on the language of the film, Khadar was advised to release it in French; he was told that the film would be better received by a larger audience if he did so. He said, “No.” He thought a Somali film should be in its mother tongue. The fact that this was in question during modern times brings up a larger issue of the digestibility of real black stories and experiences among the international audience. Khadar did not let this stop him.

When Khadar was getting pressured to shoot the entire film in a European country, he said “No” again. The film was shot in Djibouti. Though there were local logistical issues when shooting, the film would not have enjoyed its current success and glory had it been shot anywhere else other than Africa.

Most emerging filmmakers would cave in under the pressure of investors and industry veterans. Guled & Nasra, a film that Khadar finally received funding for, could have easily been dismantled before shooting. Experienced filmmakers constantly face the challenge of funding their ideas, no matter how grand their previous work may have been. However, Khadar could not be moved, even if there were to be repercussions. Instead, he relied on the power of his ability to say “No,” especially when his gut told him he was going in the right direction.

Khadar Ahmed is an anomaly in today’s world of fast opinions and unsolicited advice. He rules himself and decides his own future, despite the societal odds stacked against him. When asked what he would say to a young Somali refugee coming to Finland today and struggling with achieving their dreams because of a lack of representation or support, he said, “I would tell them to never let another person decide who you are and what you are capable of. If someone doesn’t believe in you, do not quit. Use it as a power to prove them wrong. It may not be easy and it may not happen today or tomorrow, but you keep doing it until it happens. It may take five years, 20 years, or even 50, but never give up.” Because of his humble nature, it seems Khadar forgets a major piece of missing advice to young Somalis moving to Finland today: He is the representation on which they can now rely. He (and other rising African leaders in the Finnish community) became the very representation he was looking for years ago, and he did not wait to be invited. Khadar knew when to say “No” and to persevere, even if he was alone in his ideas.

When he watched Boyz N The Hood for the first time several years ago and found out that its African American director, John Singleton, was nominated for two Academy Awards, Khadar knew that he too wanted to achieve the same level of success. “My worst nightmare as a filmmaker was that I had only made a short film. I knew I could do more, and so I did.” At the end of November 2021, Guled & Nasra won five African Movie Academy Awards including the Ousmane Sembene Best Film in an African Language, overall Best Film and Omar Abdi deservingly won the Best Actor in a Leading Role. As of December 2021, Khadar was signed to one of the most elite talent agencies in the world, Creative Artists Agency (CAA).

Khadar’s mother has seen his film four times now and even sometimes travels with him to film festivals. She reads and watches any news related to him. There has been a lot of news about her son and his film. Before its official release in theaters, the Minister of Information, Culture, and Tourism for the federal government of Somalia conducted a national broadcast to encourage Somalians to watch Guled & Nasra. Khadar has made his country proud, but no one is prouder than his mother. Hardly able to sleep, she stays up late at night scrolling the web, hearing what the world has to say about her son. She says to Khadar excitedly, “Have you seen this?” anytime she discovers a new article about him. Khadar smiles and says, “Yes mom, I have, but you must put the phone down now. You should get some rest. It is time to sleep.”