Ihnestr. 22, Freie Universität Berlin

Miia Laine is a Helsinki-based radio producer, DJ, and cultural worker. Coming from a social science and ethnomusicology background, her work seeks to critically examine and redress existing power dynamics through people’s stories. She curates Sonic Club, a gathering and lecture-series on sound, music and people.

For the past year, I have been teaching the course “Decolonise your Studies” at Aalto University with Kiia Beilinson. Settling on this title was an effort to inspire action, despite believing it’s not really possible to decolonise academia. Teaching the course filled me with feelings of inadequacy and doubt. How can we make sure this course does its name justice, especially in a colonial country like Finland that is still oppressing Sámi peoples’ rights1? Are we only playing into an empty buzzword culture that is actually damaging to indigenous rights? How can we justify teaching this course at a university, with its structures of institutional violence?

In this essay, I would like to reflect on these feelings and my experiences with decolonial work at three different universities I have studied or worked at in Germany, UK and Finland.

FREIE UNIVERSITÄT, BERLIN - Finding legacies of colonial violence on campus

I did my first degree (BA in Political Science) at the Otto-Suhr-Institute for Political Science (OSI) at Freie Universität Berlin. The campus is located in South West Berlin, a green and wealthy suburb just a few metro stops from where I grew up. I spent four years at this institute, mostly learning about political theory. I grew up in an immigrant family, and for a long time, I had an urge to understand the big thinkers and explainers of the world. I wanted to have this knowledge and be able to talk about these respected philosophers and theorists. We read the “canon”: Plato, Aristotle, John Locke, Immanuel Kant, Thomas Hobbes, Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Michel Foucault. We learned about the history of European political thought, liberalism, rationalism, and nationalism. Education was free and the lectures and seminars were packed with more than 100 people sometimes. I found the atmosphere intimidating. I never spoke. I found it difficult just to understand these theories, let alone be able to critically engage with them. Only much later did I realise that it was the unspoken eurocentrism and whiteness of the knowledge, people, and institutional structures that made me uncomfortable.

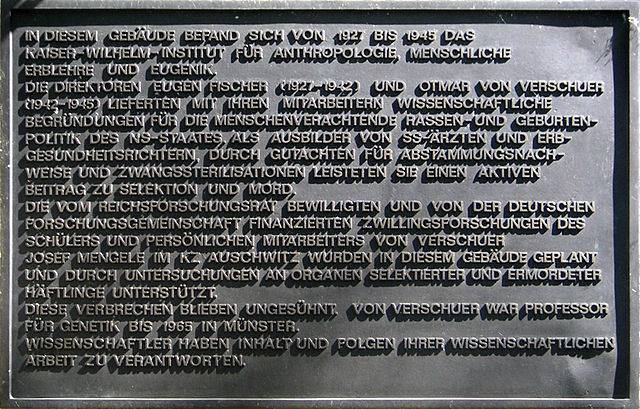

Opposite the main institute building was an older building located on Ihnestr. 22. Many of our seminars were held in the basement. In my first week, I heard one of the older students refer to it jokingly as the “Mengele-basement”. We quickly found an unassuming looking plaque on the front entrance.

What did it mean to study in a building with such a dark history? In the very same rooms that genocide was planned and pseudo-scientifically justified in?

The plaque outside Ihnestr. 22, Freie Universität Berlin

The plaque reads:

From 1927 to 1956, this building housed the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics. The directors Eugen Fischer (1927–1942) and Otmar von Verschuer (1942–1945) and their colleagues produced scientific justifications for the inhumane race and birth politics of Nazi Germany. As consultants to SS-doctors and hereditary health court judges, they produced assessments for proof of descent and forced sterilisations and made an active contribution to selection and murder.

Josef Mengele, who conducted the twin research in the concentration camp Auschwitz, was a student and personal colleague of Verschuer. The research was approved by the Reich Research Council, financed by the German Research Foundation, planned in this building and supported by examinations of the organs of murdered detainees.

These crimes remain unpunished. Von Verschuer was Professor of Genetics at the University of Münster until 1965.

Scientists carry responsibility for the content and consequences of their scientific work.2

What did it mean to study in a building with such a dark history? In the very same rooms that genocide was planned and pseudo-scientifically justified in?

Growing up in Berlin, you learn that every other building has some connection to Nazi Germany. My secondary school’s main door still had bullet holes from WWII. But, with history all around me, I learned to disassociate from it. I thought that using these buildings as spaces for learning is the best thing you can do. I thought that’s all there was to it.

During my studies at the OSI, I learned about colonialism in two classes, post-colonial theory and African political theory. In the post-colonial theory class, we read Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Edward Said, and Homi Bhabha, and in the African political theory class, Kwame Nkrumah, Frantz Fanon and others. They were good and interesting classes, but failed to make a connection to how they shaped our lives as students in that time, how they were connected to the buildings and institutions we were spending our time in, and how that history was still visible in the ways we learned and in the knowledge we learned. For a nation that prides itself with a culture of remembrance and openly coming to terms with its past3, Germany as a colonial empire was never or rarely talked about.

It was only a year after I left the OSI when a post-colonialism class with Dr. Bilgin Ayata produced an exhibition about our seminar building with the dark past: Ihnestr. 22: Manufacturing Race - Contemporary Memories Of A Building’s Colonial Past: “The exhibition aims to document the relationship between Ihnestraße 22 and German colonialism and to show how this history is remembered by people at the Institute today. We hope that this research will bring others, at the Free University and beyond, to engage with the colonial reality that exists in all spaces.”4

I realised my connection to these places and started to reflect on these seemingly far-away histories and systems we learned about in a more personal way, about how the buildings and spaces we move in connect us closer to the past.

The exhibition traced the history of the institute and how the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institute for Anthropology (KWI-A) was closely connected to the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Society, founded during the German Empire in 1911. At that time, the German Empire had occupied areas in Africa in what are today Cameroon, Namibia, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, and Togo. The exhibition talked about the often forgotten Herero and Nama genocides that happened between 1904-19085. In their research, the students found out that the attic of the KWI-A housed a skull collection that had been taken to Germany after the Herero and Nama genocides for “research”, some of which are still part of the Berlin Charité research hospital and unreturned today. And importantly, for the German Reich, such as the other empires, colonialism was primarily an economic project.

This was the first time I thought, “wow”, students at the same institute where I studied went on to connect the dots and engage with that plaque in a deeper way, finding and sharing new information and historical facts that had been hidden—something that I had the means to do equally. I realised my connection to these places and started to reflect on these seemingly far-away histories and systems we learned about in a more personal way, about how the buildings and spaces we move in connect us closer to the past.

Around the same time of the exhibition, construction workers found human bones in the grounds of the institute. In February 2021, after five years of archaeological excavations, 16.000 pieces of human remains have been dug out on the campus6. They belonged to the collection of the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institute. The fact that we were not only studying in the same buildings where genocide was planned, but actually among the very bones of murdered people, has been a harrowing continuation of finding colonial violence at the university today.

SOAS UNIVERSITY, LONDON - Decolonise, Decolonise! A political student body and institutional inertia

Feminist killjoy, academic and inspiration Sara Ahmed writes in her book Living a Feminist Life about doing “diversity work” inside universities. It is “pushy work” and will be resisted, and often the person highlighting problems becomes the problem.

In 2014, I moved to London to do an MA in Music in Development, which was part of the Ethnomusicology department at SOAS University. SOAS stands for the School of Oriental and African Studies, and, as you might expect, has a very colonial history. It was founded in 1916 as the School of Oriental Studies. It was a tool of the British Empire to educate colonial administrators, military, teachers, missionaries, and others working for the British Empire about the various ‘cultures’ they occupied, such as languages, customs, and religions, and to then send them out to the colonies to work more effectively for the empire.

At SOAS, the discussion around decolonising was more advanced than what I experienced in Berlin. Students were aware of the building’s colonial history, beginning with colonial geography: why was a school focused on Asia and Africa located in London? Discussions on how the institution’s colonial history shaped the knowledge that was being taught were present as part of every day, at least among the students. Student-led decolonising efforts, such as the “Decolonising Our Minds Society”, included questioning the taught curriculum or asking why there wasn’t a single black lecturer in African Politics. In a wider context, this was happening at the same time as the UK-wide “Why is My Curriculum White?” campaign and the Rhodes Must Fall campaign at Cape Town and Oxford University. After my MA, I stayed at the institution for three years, working at the university radio. During my time there, decolonisation was voted by students to become their number one issue, and the directorate eventually made it one of the main strategies: “Supporting further recognition and debate about the wide, complex and varied impacts of colonialism, imperialism and racism in shaping our university”.7

Still, there seemed to be a sort of big divide within the institution. The colonial idea of getting to know so-called ‘world cultures’, multiculturalism and exoticism was still uncomfortably present in many spaces.

Feminist killjoy, academic and inspiration Sara Ahmed writes in her book Living a Feminist Life about doing “diversity work”8 inside universities. It is “pushy work” and will be resisted, and often the person highlighting problems becomes the problem. She talks about institutional inertia, about how institutions, even when talking about issues, are often not willing to change:

“Even if diversity is an attempt to transform the institution, it too can become a technique for keeping things in place. The very appearance of a transformation (a new, more colorful face for the organisation) is what stops something from happening.”9

This is what I felt was happening at SOAS. There was lots of excellent campaigning and organising by students and very few committed faculty, even some from the directorate, but the structures of the old institution seemed too rigid for anything major to change.

Eventually, there were some actual changes to the curriculum. An example that I would have liked to have experienced myself in my early BA years was in International Relations. Faced with the issue of how to deal with the eurocentrism of the ’canon’, some lecturers redesigned their courses to give more context. The ‘Introduction to International Relations’ course added four weeks of disciplinary framing at the beginning of the course that covered the historical origins of international relations. Students were introduced to how international relations theory came out of the time of colonialism and empire and why the canon actively erases colonialism and empire from its texts. The redesigning of the course broadened the perspective to not only teach international relations theories, but to give students the tools to critically engage with the discipline as a whole.

My time studying and working at SOAS was marked by the institution’s many paradoxes: a place where incredible and inspiring critical thinkers and lecturers worked, a critical space for questioning the institution, with many autonomous spaces for students to build networks, and at the same time, a place where colonial legacy shapes resistance to actively changing structures. Marked by funding cuts and Brexit, it was also a time of increased businessification of the university, something we’re seeing around the world.

AALTO YLIOPISTO, HELSINKI - Working with doubt

In 2018, I moved again. This time to Helsinki, Finland, where I had family connections. Working as a freelancer in music, radio and educational environments, I have been co-teaching the ‘Decolonise Your Studies’ course at Aalto University this year. Aalto University includes the schools of Technology & Engineering, Business, Art & Design. The course was initiated by the UWAS10 department whose courses are open to all Aalto students.

Decolonize your studies course picture, by Kiia Beilinson

The short course focuses on asking questions about how colonialism has shaped universities, knowledge, and teaching. The challenge of the course was the vastness of the topic; it can be difficult to stay concrete. We didn’t believe a lecture series of “this is what decolonising is” was appropriate, so we gave students different input such as reading material, guest lectures, films, a lot of time to reflect on their own discipline’s histories, norms, and power dynamics, and also on their own feelings that came up during the course. At the end, there was a group work presentation, which we made into a zine. We ask more questions than we answer; you can only do so much in seven weeks. We tried to plant seeds from which the students could carry on.

In one of the guest lectures by Maija Baijukya, we found out that Finland, despite being a fairly small country in the EU, was the fourth biggest owner of land outside the EU, only behind the UK, France, and Italy. In 2016, Finland owned approximately 567,000 hectares of land in Brazil, Uruguay, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, and China, mainly used for forestry companies11. This fact really stayed with me. Towards the end of the course, I found out that Aalto University has direct partnerships with some of these forestry companies: UPM and government-owned Stora Enso. UPM has a ‘sustainability design’ partnership with Aalto12, whilst Stora Enso is participating in a start-up accelerator programme13. It also owns half the Brazilian company Veracel. Their practices growing eucalyptus plantations for pulp have been called neocolonial by locals and indigenous groups14, and these monoculture plantations have damaging effects on local ecosystems, such as drought.

Is teaching a course about decolonisation in institutions affiliated with neocolonial practices a total farce? Who benefits from this? Does the institution only allow this kind of course so it can tick the box of doing decolonising? Is it, on the other hand, a necessary and rare critical space within the institution in which these conflicts can be addressed?

Is teaching a course about decolonisation in institutions affiliated with neocolonial practices a total farce? Who benefits from this? Does the institution only allow this kind of course so it can tick the box of doing decolonising? Is it, on the other hand, a necessary and rare critical space within the institution in which these conflicts can be addressed?

Even after having facilitated this course, I think my relationship to decolonisation is very limited to uncovering hidden histories and structures of past or ongoing colonialism. I find it important to understand how 500 years of European colonialism that was rooted in a capitalist venture for profit maximisation is present in all parts of society today, and especially how this presence is being actively erased or denied.

But once we find our connections to colonialism, once we find the bones of genocide in the same grounds we were taught about Enlightenment, once we’ve taken down the statues and celebrations of colonialism, once we’ve talked about it, shared it, taught it, felt angry and sad, made exhibitions and events and magazines about it, what next? To be honest, I don’t know. I think it’s crucial to have spaces like this for students to get together and learn and build networks; community has been the biggest value to come out of this for me, but I doubt it will have much impact on how the university operates.

My journey of learning about decolonial practice has been filled with this doubt. I doubt the true intentions of universities proclaiming to decolonise themselves. I doubt the histories they are remembering and wonder about ones that have been hidden. I doubt the meaningfulness of a course like this in a neocolonial institution. I doubt the rightness of my own motivations.

But what does this doubt actually mean? When I doubt something, I don’t believe that something is as it’s presented. When I doubt someone’s intentions, I don’t trust what I have been told to be true. When I doubt my abilities, I question whether what I have told myself or what others have said about me is true.

For there to be doubt, it takes two opposing forces that cannot be reconciled, resulting in a mismatch. And, seeing doubt as a state of existence between contradicting forces, I think this is a very fitting description for decolonial work. And it’s not a bad thing. I believe it’s a necessary part of it.

When I feel doubt about the limits of this work, how it’s very unlikely to change anything structurally, when this doubt causes too much inaction or introspection, I try to accept this conflict to spur me on. I think it’s good that I’m feeling doubt; it shows it’s not simple and straightforward, it’s something worth sticking with.

Sara Ahmed discusses the work we do when we do not quite inhabit the norms of an institution, when we don’t “dwell so easily where we reside”15. Doing this work then becomes making friends with questions, embodying the question, residing in the question. Can you also reside in doubt? There has been a lot of discussion around bearing the uncomfortable, but how about bearing or even embracing the doubt? I try to let doubt carry on the work sometimes.