Fjolla Hoxha is a writer and performance artist from Prizren, Kosova. She studied Dramaturgy at The Art Academy /University of Prishtina, Critique of Theater & Drama at Istanbul University/ Faculty of Philology and is currently pursuing a graduate degree at the Theater Academy / University of Arts Helsinki, Finland in Live Art and Performance Studies.

A review of ‘Sarajevo Roses and Clouds of June’ exhibition by Samra Šabanović and Sheung Yiu at Third Space, Helsinki.

How often do we think about what we are doing when we pull our phones out to document a fleeting moment in time? Besides fragmenting the experience between living it and filming the ephemeral to turn it into a ‘transit visa’1, how much do we pay attention to what is happening in the peripheries of our focal point? What dynamic does an image capture and what dangers does it pose to those involved in this dynamic? Ultimately, what does it leave outside?

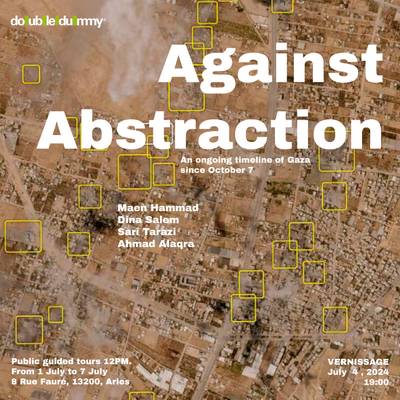

Sarajevo Roses and Clouds of June2 is the third chapter of a lengthy research and public interventions series on photographic images, on the significance of images in relation to their socio-political meanings, within the larger project titled ‘I was there, but you didn’t see me’ by Samra Šabanović and Sheung Yiu. The researcher artists juxtaposed data that exposes the purposeful othering or the detection of marginalized bodies through surveillance systems, mainly via facial recognition, to then disrupt this reproduction by applying methods of counter vision (a term defined by Czech philosopher Vilém Flusser in The Village Cry journal, 1977) that enable the reading of what appears to be non-present at first glance.

At its core, the whole research is built on the thesis of analyzing the relationality between documentation of someone else’s struggle and how the non-dialectical way of doing this exposes the documented to the very powers that repress them.

I recall a few personal instances where taking someone’s picture would have posed a threat to them. One that I remember clearly was in a nightclub in Rabat, Morocco, a few years back, where my friend and colleague Adbellatif had taken us, a bunch of adventurous and exoticizing tourists, up for a round of dancing and a few rounds of drinks. Someone among our crowd took out their phone and invited everyone to gather to take a picture, a memoir of this moment to remember, probably to post on social media as well. Abdellatif jumped swiftly and begged us all to not take photos in the club, as this, by an accidental inclusion in the image, may discredit and endanger the privacy of those whose families, and public opinion in general, don’t support them in their inclination to exercise non-conventional freedoms that deviate from the normative lifestyle.

“Images are real. Images we choose to make (or not to make) incite real changes. Far from merely representations, Images are THE event itself. The interventions engage images to have a dialogue with the public audience, to speak about their desires and the secrets they hide.” (Excerpt from video text)

To complement with a personal experience, what Samra states at the very beginning of the video essay, “war photographers know that giving visibility no longer justifies their presence in war zones and the photographs they bring back. The accountability and humanitarian aid they promise never come”. After the war in Kosova, where I am from, my mom worked as a translator for the news production company from the UK, ITN, which also made a reportage about me, recalling my experience during the war and sharing the enthusiasm that the post-war freedom brought in terms of reclaiming the rights that had been taken away from me.

War photographers know that giving visibility no longer justifies their presence in war zones and the photographs they bring back. The accountability and humanitarian aid they promise never come.

During a conversation with the journalists, my dad humbly shared his appreciation towards the foreign media for letting the world know what we had been through. The journalist responded with mathematical facts about mass media; that what is shot for hours and edited to, say, a 2-minute reportage, swipes through the TV of a white collar Britt, as a background of a morning routine while they are on their way to getting ready for work, thereby brushing off our tragedies as soundscapes over morning coffee.

These are only two memoirs of many that bring me close to the theme and form of elaboration in Sarajevo Roses and Clouds of June, yet I acknowledge that the artists’ personal experiences and their reflections, which I am sympathetic towards, can never be fully graspable by anyone else but them. And this is where the artist would want us to be. To stop and rethink the concepts of identification, representation, victimization, sympathy, and empathy and how our engagements with any of these shift the positions of power(lessness) on others.

In fact, when visiting the exhibition and talking to the lovely and hospitable Samra and Sheung, who were always there and eager to have a conversation, I noticed our proximity was being built due to our common experiences of having lived through conflict and upheaval. There were moments when one’s shared experience triggered a similarity the other was eager to share, situations engraved in our skins, nuances of which we were able to read fluently among us. I second their claim in the video essay that “Once you have seen war, you cannot unsee it.” War is visible everywhere. Once one has lived through conflict, it follows them everywhere. The vigilance to see the power structures bare or the “truth that is not true” (Jennifer Lai, Hong Kong photographer) is everlasting.

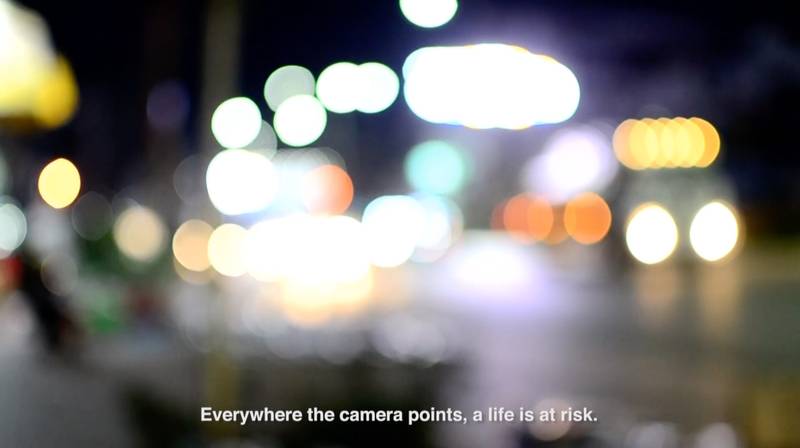

“Everywhere the camera points, a life is at risk.” (Excerpt from the video text)

The artists bring to the surface the well-known parallelism between pointing the gun at someone to shoot them and shooting as a term that describes the process of capturing an image. The image exposes political standpoints and identifies those who pose a threat to the leading positions of authoritarian powers. To speak in Susan Sontag’s terms from her timeless essay collection ‘On photography’:

Photographs really are experience captured, and the camera is the ideal arm of consciousness in its acquisitive mood. To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge — and, therefore, like power.3

What comes through as a not-so-obvious realization is that we forward this system of condemning, both by making it visible as well as by making it invisible via the narratives we choose to tell or not through images. These narratives become even more powerful, and hence more crucial and dangerous, through their viral multiplication via social media. There have been times I have felt guilty for not exposing my sympathy for my countries’ national prides, pride parades or struggles, Palestinians or Charlie Hebdo, by painting my profile picture on social media with a slogan or a flag, but this is the power of the mutual surveillance mechanism that puts us in the position of policing not only others but also ourselves, a power that I am not willing to feed into. A readily self-served surveillance mechanism through tags and check-ins. The same images, however, give us voice, take space, make us accountable and diversify the content of the digital realm, although it is their curation via algorithmic systematization that more so decides their dissemination and the duration of this visibility.

There have been times I have felt guilty for not exposing my sympathy for my countries’ national prides, pride parades or struggles, Palestinians or Charlie Hebdo, by painting my profile picture on social media with a slogan or a flag, but this is the power of the mutual surveillance mechanism that puts us in the position of policing not only others but also ourselves, a power that I am not willing to feed into.

“Humans and images are now entangled in the network, each controlling the life and death of the other. Visibility is not just a picture; visibility is lethal.” (Excerpt from the video text)

Samra and Sheung are asking what photography or moving image does to the bodies it represents, those it leaves out of the frame and what it exposes in terms of socio-political relationships within the hegemony of the power structures that reign us.

“Unless we stop indulging in metaphors and start to recognize the politics of visibility and invisibility within the power structure, ‘photography’s future will be much like its past. It will largely continue to illustrate, without condemning, how the powerful dominate the less powerful.” (Excerpt from artist’s statement).

Through the vast presence of technology and network, the visibility/invisibility binary carries its own negation within specific geo-political contexts, an approach which opens the possibilities to debate the pros and cons of capturing imagery, depending on the circumstances. The artists argue that while protecting the identity of the protesters during the Black Lives Matter movement by calling for the blurring of protesters’ faces, ’on the other side of the world, in Hong Kong, pedestrians are filming the arrest of the protestors on their smartphones as they shout their names and ID numbers, in the hope that their families and lawyers know which police station to look for them, in the fear that they won’t see the sun’4.

‘What qualifies as an image of peace?’ is a major conceptual question that comes through the work of Sheung and Samra.

“The video essay is entirely composed of video footage found on popular free stock websites. In five chapters, the essay delves into the ever-complex politics of visibility and invisibility, offering a critical examination of how photography may or may not contribute to peace in the age of mass surveillance enabled by hyper-connectivity and the omnipresence of cameras.” (Excerpt from artist’s statement)

Most of the images that build the video resemble touristic commercials that represent ‘exotic’ destinations. They move in slow motion and are somehow kitschy utopian, representing a generalized image of the Western middle class on holidays. The textual side of the video orients the viewer towards the direction the artists would want their viewers to see these images which is through the lens of their hidden subtexts that mainly ask what is being kept away.

“A photograph conceals as much as it shows.” (Excerpt from the video text)

Based on Samra’s words during our discussion: ‘An image is always something else than what you see’. The work achieves this effect by producing a sensation of annoyance, almost disgust towards the images showing the undisputed position of the western middle class, viewing non-Western cultures as exotic through devouring their cultural stereotypes, natural beauty, and leisure investments by the neo-liberal corporations.

I can not refrain from bringing up Sontag’s perspective on how the discovery of the camera has in fact equipped the leisuring middle class with the short term illusion of having control over their lives by belonging to a higher power strata.

Photographs… help people to take possession of space in which they are insecure. Thus, photography develops in tandem with one of the most characteristic of modern activities: tourism. For the first time in history, large numbers of people regularly travel out of their habitual environments for short periods of time. It seems positively unnatural to travel for pleasure without taking a camera along. Photographs will offer indisputable evidence that the trip was made, that the program was carried out, that fun was had.5

During our conversation about these images, Sheung said: "Counter-violence is also using these images without permission, although they were public’. The video elaborates at length on one of the crucial questions of journalism, the documentation of violence and what this does to the subjects that are documented.

The voiceover narrative in the video essay channeled by Samra: “By turning violence into images, it allows them (war photographers) to safely walk away from them” (the subjects of the image) is juxtaposed with an image of a tiger devouring the ribs of what may have once been a deer… or a weaker tiger. This representation recalls Franz Fanon’s use of the term “species”, which “harkens to the animal terms colonists use to describe the colonized, who the colonists believe are savage and bestial.” 6

“Photography decontextualizes violence.” (Excerpt from the video text)

Through the geographical positioning in various contexts, the artists’ research aims to expand the binary positions of what it means to document violence, and they put a claim on the inability, or rather impossibility, to represent victims.

The form of delivering the text is equally important to its content. Samra’s and Sheung’s voices (which one recognizes as the artists are at the exhibition space, greeting their guests) have an informational and conclusive tone. They interfere and overlap each other’s sentences. Often, one begins at the end of the other’s sentence. This dramaturgy reveals a collective thinking and recognition of each other’s capacity to build new discursive approaches towards the understanding of the relationship between image and narrative, which as a horizontal collaborative format may stretch to economic equality as the only path to peace.

The artists don’t use music, which is so well known as a powerful tool in moving images to manipulate emotions. The absence of any other sound but that of the voices of the narrating artists with their foreign accents to English language, leaves a lot of room for the audience to be in touch with their own affect and critical mind.

Through their everyday presence, Samra and Sheung made sure that they were seen and, through being seen, they made their audiences visible and valuable.

To expand the view from the video-essay into its exhibition format, I’d like to describe how Third Space was curated. I found the space quite fitting for the video pop-up, primarily because of its size, which offers an intimate experience, countered by a large display window. There was a large flat screen on the window replaying the same video-essay that was being screened indoors, which distorted the external reality. Moving images of safaris and resorts supposedly located in exploited countries, gained another layer of meaning in their interaction with the grim and rainy, yet peacefully operating streets of this posh area in Helsinki.

Small, almost icon-like images of protesters whose eyes had been blurred were scattered around the hardware base of this screen and were visible from the exterior of the venue.

What makes Sarajevo Roses and Clouds of June a special exhibition for me is the agency that its authors take by being at the Third Space for the duration of their exhibition, to facilitate their work and be with their visitors in a very smooth and informal way. Through their everyday presence, Samra and Sheung made sure that they were seen and, through being seen, they made their audiences visible and valuable. I find this form of approaching one’s own work very humble and respectful of both oneself and the audience. If they weren’t present, the exhibition would have gained a completely different meaning and would have emitted a different feeling.

Although the video essay presented by the artists is a manifesto-like statement reached by a thorough scrutinization of the art of photography and documentation, they keep the door open to situation-specific interpretations that justify the need to show or hide in this ‘game of hide-and -seek’, as said in the video essay.’ They (images) are a grammar and, even more importantly, an ethics of seeing.7

Should the viewers take responsibility for discursive readings of history that photography engrains both by showing and hiding, we’d come to a more optimistic perception of the future as laid out by curator, filmmaker and professor Ariella Azoulay. ‘Viewers, through careful observation of images of horror, become witnesses who “can occasionally foresee or predict the future,” she writes. As a result, they can warn others of “dangers that lie ahead” and take action to prevent them’.8