Olga Spyropoulou (b. 1985, Athens) is a Helsinki-based performance artist and writer. In her work, she experiments with various modalities of spect-actorship and non-hierarchical methodologies. She is interested in how we relate to one another in different contexts. Her artistic research revolves around legal contracts as performance scores, with respect to both private and public commitment.

Book Review: Performing a Lifetime | Written by Saara Mahbouba | Illustrations by Gladys Camilo | Format: Hardcover, 11 x 14 cm, 64 pp | Date and Place: 2021, Helsinki/Mexico City | Price: 23 EUR | Published by quince ediciones

It’s not often that a book makes you smile the moment you hold it in your hands. I smile at the paradox of a lifetime fitting into such a small space and because there is joy for me these days when things appear in a size that I feel I can carry, a size that is not going to weigh me down. I am an immigrant in Finland. I have had to move houses three times in the past year, and this small book, published by quince editiones1, seems to get me: it has an itinerary similar to that of a freelance cultural worker, designed in Mexico, edited in Finland, and printed in Estonia. It is even supported by grants from Frame and Taike, just like some fortunate Finland-based artists. This book already feels somehow familiar.

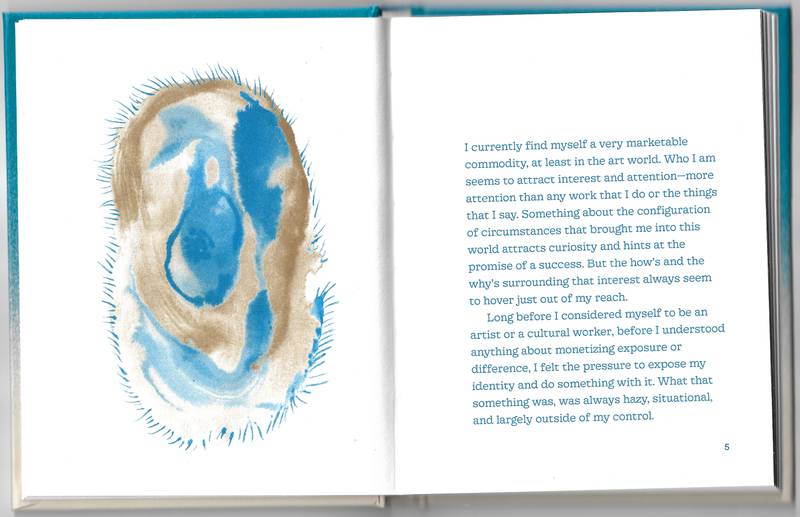

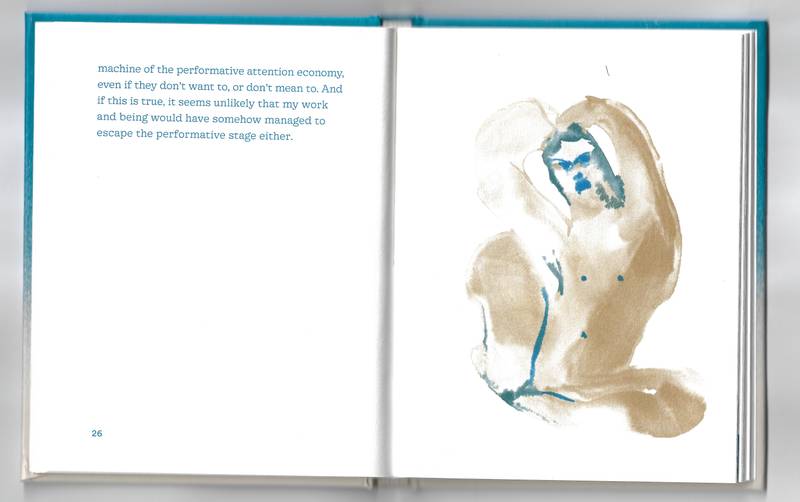

Flipping through the book, pages of drawings by Gladys Camilo are dispersed in-between pages of text by Saara Mahbouba. The word symbiosis2 comes to mind, partly due to the hypnotic quality of Camilo’s drawings that evoke their own private evolutionary theories page after page, and partly due to the book’s irreverence towards the hegemony of the text. Different shades of blue meet with various tones of brown: merging, inflicting wounds on one another and leaving; making sense and unmaking it, but ultimately revealing the "ecologies of identity and trauma"3 that constitute a being.

“To perceive is to make a representation”4; fragments of Camille Auer’s the smallest movement pop into my head while exploring the drawings in Performing a Lifetime. There is a calculated abstraction in Camilo’s work that disrupts pattern recognition and thus perception, conjures the politics of seeing, and contrives questions around identity, definition, and representation5. Every time I go back to a drawing, I slip. I seem not to be able to understand it fully; there’s always something amiss. This hovering between clarity and diffusion is both soothing and frightening, and it lends the book a distinct temporal quality, as the drawings require the viewer to move slower and spend more time with each page.6 Here is an articulation and a negotiation of trauma through form. It is Camilo’s poetic response to oppression and a strategy for decolonization. Yet, it is not the only strategy offered in Performing a Lifetime.

Saara Mahbouba’s writing is far from opaque; it is situated, clear, and urgent. Her text “hovers around the confessional, the biographical, the self”7. It follows the tradition of intersectional feminist theorists whose writing emerges from everyday life experiences and “enables us to remember and recover ourselves and […] renew our commitment to an active, inclusive feminist struggle”8. That is to say, this writing contains a lot of pain and cruelty9; it requires hard work because it asks unapologetically for self-reflection and generously gives words to things that diminish us. Yet, it manages to remain hopeful and to offer concrete strategies for resistance. Saara Mahbouba writes to understand when and how the “configuration of circumstances that brought her into this world”10 – Mahbouba is half-Iraqi half-Finnish born and raised in the United States11 – became the repertoire of selves that she was expected to perform on demand. She gives a nuanced account of instances, from her early childhood in the California of the ‘90s to the present day and her experience of the art scene in Finland, when she felt forced to perform a requested fragment of her race or ethnicity. Through her self-reflection, she weaves an elaborate net of interconnected causes that elicits the performance of her identity as labour. In this net, actions and feelings are intertwined. The coercion to perform comes in different forms and does not always originate explicitly and directly from others.12

Even though Mahbouba shares with honesty and vulnerability her experiences of racial tension that range from microaggressions, fetishization, and exoticization to even more overt racist behaviours, her text is not built around the narrative of the marginalised, suffering body. Not at all. Mahbouba consciously refuses to inhabit that space and demands from all bodies who are constructed to fit under the category of the “marginalized” to coalesce; to imagine and create spaces of their own making. She urges artists to refuse to be reduced to a buzzword such as “marginalization” and resist having their art displayed and flattened by the institutions that support the system that pushes them towards those margins in the first place. She asks those bodies not to perform revolutionary thinking within institutional confines that reproduce inequality but to start holding conversations outside market interests and hegemonic discourses. Her suggestions remind me of Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s question: “If we eliminate the pressure to pass, what delicious, devastating opportunities for transformation might we create?”13

Mahbouba is not oblivious to the fact that it is not only her ethnicity that make her “a very marketable commodity”14 in the art world but also her privileges in terms of mobility, education, and financial status, to name a few, as well as her ability to pass. She describes the fascination of curators within the Finnish art scene when her identity is mentioned. She shares her disillusionment about initiatives that aim to offer space and centralise marginalised voices and points out the traps of such initiatives. They pit marginalised artists against one another, and in the end, they only allow the least oppressed members of the group to enter the institutions: those who probably were somehow already in15. “Didn’t each of us reach this place already, this institution, conference, or gallery? Everyone being spoken to made it here already, for whatever it’s worth.”16 Mahbouba exposes the disparities between what institutions and platforms claim they do and what they end up doing.

While Mahbouba offers a critical approach to these elite spaces that claim to offer their space to “marginalized bodies” but do not contemplate their working structures, policies, and practices, she lets them off the hook too easily as “the master’s tools that will never dismantle the master’s house”17. Instead, she turns her focus on the community of “us,” the artists whose practise stems from and deals with identity or difference. And while she offers useful strategies18 to avoid self-exploitation and the performance of one’s identity as labour for these same platforms and institutions, she seems to be falling into one of the traps that she has alarmed us with: placing all the expectations for change and transformation on the marginalised bodies.

Reading Mahbouba’s text, I too started contemplating the timing of when identity politics emerged in texts regarding my artistic practice. When did I start performing fragments of my identity as labour for the art institutions? Unlike Mahbouba, I remember how irrelevant my migrant status and my sexuality felt when I wrote my first grant application in Finland three years ago, trying to make work as an artist while being a student in the MA Live Art and Performance Studies in the Theatre Academy of Uniarts Helsinki. I remember thinking hard and deciding not to include anything regarding my geographical and sexual orientation in the introductory text. The decision not to use any identity markers was partly informed by my privilege: being white, able-bodied, cis-gendered, and coming from a white, EU, middle-class, academic background, my art seemed not to be concerned with identity politics – I was still under the “abstract, conceptual art” spell. Yet, it was also informed by the negative connotations that those markers carried covertly in the language19 of the grant calls of the funding bodies: the stereotypical infelicitous narratives where “identities are only seen as valid when they are being defined as suffering”20. Was I suffering? At the time, I didn’t give it more thought; I was on a deadline. However, even now, I still have the bodily memory of “something not feeling quite right” when making that decision: I knew I was lying mostly to myself when I believed that it was my choice to think of my identity as irrelevant to my artistic practice, and somehow I felt forced to go along with that lie.

I understand today that I unconsciously decided to remain opaque on paper, just like in Camilo’s drawings. I refused to become recognizable but not recognized. I refused to give away the words that in my private life brought me joy, warmth, friends, lovers, and community to be appropriated and used to injure all of us. That is why I find great comfort when Mahbouba advocates in Performing a Lifetime not to leave identity behind but to centralise it in a different way. To treat it as a resource for the community and not as a career building block. In her suggestion to build spaces “where each of us can own and work from our full, complex identities”21, I hear an array of diverse, idiomatic languages. I hear the freeing possibility of “no longer having to perform hegemonic expectations of ourselves for survival”22, not worrying if our formulations will be legible to structures that are reluctant to give away even the smallest fragment of their power to support the vision of a just, fair, and equitable world.

Yet, my question comes when thinking about how those spaces will be supported, how they will be organized, how they will be maintained. Because I find that one of the reasons that my artistic practise has been oriented nowadays around performing my identity is undeniably my longing for a community and also the lack of resources to create both the circumstances that will make a work that is not centred around the performance of my identity possible and support the production of the work itself. In Sonia Boyce’s question: “Are we only able to say who we are, and not able to say anything else?”23, I have to say that it takes time, effort, and lots of resources to create the space where you can say anything else, and by then you may be too exhausted to do it. And some people simply cannot afford to get that far.

That is why I said earlier that Mahbouba falls into the same trap that she has alarmed us with. The unfair burden of pushing for change seems to fall only on those bodies that are already burdened by discrimination. Is it only their responsibility to advocate for change? The simplest answer, admittedly a naïve one, is that whoever holds more power over a situation also holds more responsibility to transform it.

Following Mahbouba’s critique of institutions, I share her frustration and disillusionment. However, I strongly believe that we should stay with the institutions and their discourse. We should engage them with strategies such as affirmative sabotage in mind. We should hold them accountable for their mission statements and public announcements24, and demand that they make space and create conditions for long-term, material support for a plethora of initiatives by and for marginalised artists. And when I say marginalized, I share Mahbouba’s concerns about the reach and application of the term. And when I say a plethora, I mean that we need to alleviate the burden of representation on marginalised bodies. And when I say long-term, I mean that we need to scale the world according to its measures. Four or even five years is not long enough for a newly formed initiative to be able to survive without support. How long did it take for whiteness and patriarchy to set up shop? How long did it take those same institutions who now pledge equity to not be dependent on state funding? If that’s ever the case.

I breathe and dive once more into Mahbouba’s writing. The rhizomatic quality of her thinking allows various lines of flight to appear within reach. I surrender to its flow and turn the page. A strange organism lives there, composed of hues of blue, brown, and white. I understand now; Performing a Lifetime binds us together. We touch, we collide, we transform. We make worlds. And every day, great things turn a little smaller to fit our lifetime. "Sun makes the day new./Tiny green plants emerge from earth./Birds are singing the sky into place./There is nowhere else I want to be but here.”25