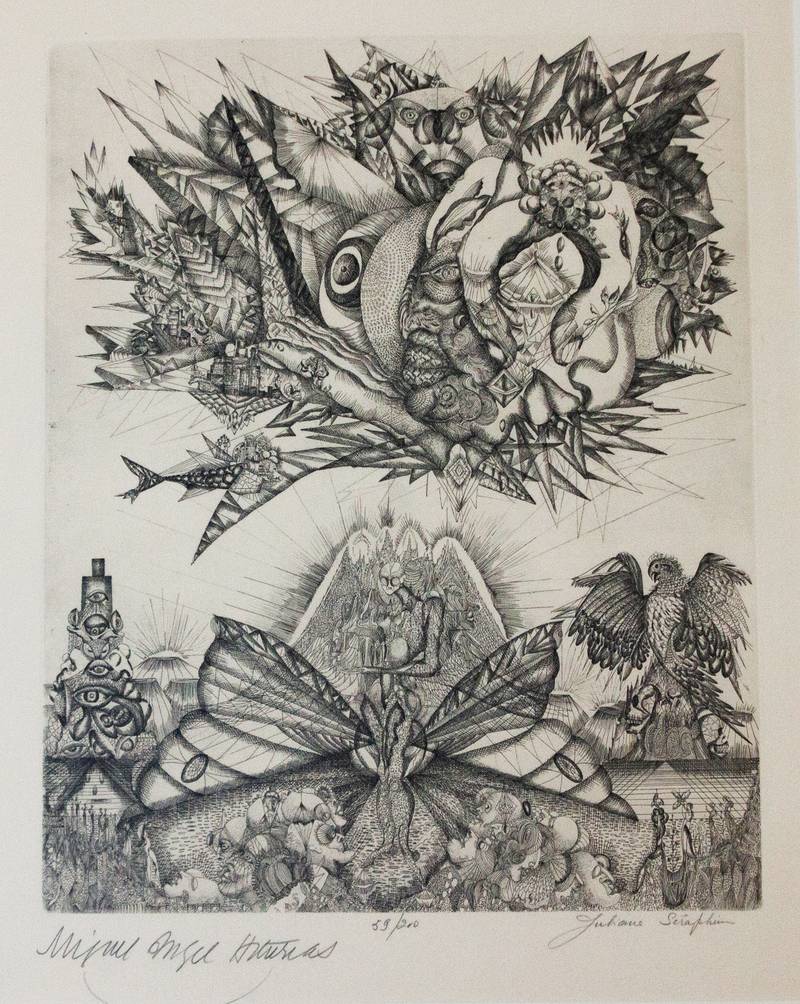

Juliana Seraphim, Asturias II (1971), Etching, 26 × 19 7/10 in, 66 × 50 cm

Sanabel Abdelrahman is a postdoctoral fellow at MECAM/Tunis University. Her research focuses on magical realism in Palestinian literature. She completed her doctoral degree at Philipps-Marburg Universität and her Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees at the University of Toronto. She is interested in cinema and visual arts. She is a writer of fiction and essays.

Some nights, if I am lucky, I would dream of Palestine. My nocturnal mind would take me to the beach of Gaza, or to a forest to stroll with my mother, or would place me standing over a rock mountain facing the sea, with other Palestinians around me who are loud with laughter, their bodies glistening with salt as they prepare to jump under the summer sun. My heart swells to the size of my waking-life melancholy and crashes to pieces when I wake up. I had never set foot in Palestine, but sometimes I am invited to visit, for a little bit - just enough to keep Palestine’s memory fresh in me, loving and life-giving like an idyllic summer day; and to fuel my attempts at return, four generations in.

We know that dream spaces, as ultimate manifestations of the ethereal, enigmatic, and fascinating as they are, tend to be relegated to the realms of the unfathomable, the unknowable, and the eternally inaccessible. Psychologists and their close companions, the surrealists1, have always foregrounded dreams either as an otherworldly oracle of human consciousness or as the only unhinged space blossoming with ‘real’ human experience devoid of boundaries or hindrances. Those approaches to the dream space, however, rarely include the more malignant and even violent desire to occupy the spaces whence those dreams emerge. Palestine, as a historic, sacred, and contested space exemplifies this in immaculate ways.

The vision of Palestine, which to me (a Palestinian who has never visited it) is intimate, maternal, and life-affirming, exists diametrically in the dreams of those who have wished for centuries to occupy it. Palestine, and specifically, its awesome Jerusalem, becomes a utopic figment in the minds and imaginaries of Western cultures who feel entitled to this small, historic land, and who employ every means necessary to possess it materially. In Dante’s Inferno, Jerusalem is the ultimate purgatory that exists in an inhabited land. In William Blake’s “Jerusalem” poem, the eponymous city is presented not as a real, physical space inhabited by its people, the Palestinians, but as a synecdoche for heaven that is transportable to a London that is riddled with what he calls “dark satanic mills.”2 Similar is the British Mandate’s Handbook of Palestine, which invites British “travelers” to Palestine “to experience the charm of its scenery and climate, to come into contact with its history… and above all, to hear the voice of its spiritual appeal”3.

The Palestinians are almost completely absented from the book, except when it is stated that “the Arab population falls naturally into two categories: the nomads (bedawai), and the settled Arabs (hadari). The former are the purer in blood, being the direct descendants of the half-savage nomadic tribes”.4 Even though this book for the British traveler painstakingly describes the “spiritual appeal” and the logistics of traveling to Palestine to such an extent that the price of train tickets and meal plans are included in the handbook, the Palestinians never are. And so, Palestine is not only effortlessly transferable to the likes of England, but is also defined as being a faraway, mystical, uninhabited space. Indeed, it exemplifies one of the foundational Zionist statements regarding Palestine being “a land without a people”. Thus, Palestine becomes a placeholder for the Western mind in seeking the ultimate dream or nightmare space; a mere ethereal piece of the colonizers’ collective imagination and violent desire.

![Paul Kor’s 1965 poster ‘land ohne winter- Israel’ [land without winter- Israel]. Source: Israeli Airline Museum website](/images/ckbxidbsrmd4dbk7gqx0-800w.jpeg)

![Paul Kor’s 1965 poster ‘land ohne winter- Israel’ [land without winter- Israel]. Source: Israeli Airline Museum website](/images/ckbxidbsrmd4dbk7gqx0-lqip.webp)

Paul Kor’s 1965 poster ‘land ohne winter- Israel’ [land without winter- Israel]. Source: Israeli Airline Museum website

Zionist travel posters make up an accurate medium that attempts to mimic the Zionist settlers’ claims to Palestine as a European heaven. Oftentimes, those posters depict Palestine as a utopia for the tired European, an atemporal, ahistorical space that exists outside the boundaries of geography and reality; indeed, a dream. So much so, in fact, that apparently, as this poster tells us, “there is no winter in Israel”. We see a woman smiling at the viewer, inviting them to join her in the land where there is no winter. Behind her stretch circles of blue, alluding to the sea and blue skies, unlike the familiar European skies that are often grey and heavy with rain. This empty exotic land where there is never winter mimics, poorly and transparently, the Western distorted longing for sunny spaces, blue skies, and the tranquil ethereal—a longing that bloodily and aggressively translates into colonization, which in Palestine still (directly) persists.

This ‘poetic space’ to which the European feels entitled emerges upon leafing through Gaston Bachelard’s famous The Poetics of Space5, that describes the unbounded pleasure of enjoying intimate spaces that are usually secretive, small, and ingrained in childhood glee. Yet, a jarring disconnect emerges between the book and the application of its allegedly universal poetics. This wistful, nostalgic solitude that, according to Bachelard, is experienced through “vital space”6 in safe homes is inapplicable to Palestinians who live either in Gaza, the biggest open prison in the world, or in other parts of historic Palestine wherein the Palestinian is either confined or treated as less than a second-class citizen. It also doesn’t apply to Palestinian refugees and the diasporic communities who endure an intergenerational pain that deems any other house in any other country counterfeit and cold, even four generations after.

The privilege of Bachelard’s safe place, in which the Palestinian (as well as the Iraqi, the Syrian, the Yemeni, and other Arabs) is able to enjoy a vital, poetic space is not possible. Rather, the Palestinian is being constantly deprived, through physical apparatuses such as Israeli bombs, land confiscation, and demolishment of houses, from enjoying the serenity of safe solitude in which the poetic or ethereal connection to the space and to oneself is possible. One can even opine that it is precisely those dreams of solitude and tranquility that facilitate the Zionist urge to force a metamorphosis of Palestine, the real place with real people, into an ageographic, amaterial space in which settlers can practice, unrelentingly, this dream of solitude that Bachelard describes.

In other words, the very promise of a collective daydreaming, an ethereal existence altogether, is presented as a possible outcome through the occupation of the real Palestinian space by the Zionist settlers, thereby transforming the real space into an effervescent space of Western dreams of solitude. This ‘promise’ of a future euphoric exultation thus makes up the premise of occupation in very real and very aggressive ways. It facilitates the settlers’ practice of beating Palestine into their image of an exotic utopia; a vision; a dream. This paranoia and the need to occupy the dream spaces of the colonized are accompanied by a similar need to occupy the dreaminess of the physical space. The colonization of Palestine is the embodiment of those bifurcated practices. And so, the representation of Palestine as a utopia emerges, which acutely contrasts with the real, physical space of historic Palestine.

the very promise of a collective daydreaming, an ethereal existence altogether, is presented as a possible outcome through the occupation of the real Palestinian space by the Zionist settlers, thereby transforming the real space into an effervescent space of Western dreams of solitude.

I often think of how this collective dream of solitude has permeated the physical occupation of the Middle East and Latin America generally, and most specifically, and to this day, directly of Palestine. I think about the white British men who wrote poetry about love and raped enslaved black women; who stole sculptures and placed them in big transparent boxes in spacious, depressing museums. I think of how when living in Toronto, on ‘Remembrance Day’7, thousands of poppies would blossom on the suits and dresses of Canadians with little labels that say “lest we forget” while collectively, absolutely, and intentionally forgetting the indigenous peoples of the land and the massacres they had committed against them. I think of how French and British men battled in the forests of Turtle Island over the graves of thousands of indigenous children tortured and killed by their churches. I think of how early Zionist settlers tried to paint, with excruciating detail, the landscapes of Palestine because they could not see it or experience being present in its awe; of how they hung prayer rugs on the walls of pubs8 because they could not escape the Western mentality that dictates keeping continents between the object and the self: a paranoia of intimacy. All of this was done in an attempt to occupy the dream space of the colonized and to occupy their very material environment so that they, the Western colonialists, could practice dreams of solitude in the dewy forests of Latin America, the sunny open spaces of Africa, and the rock mountains of the Middle East.

This heavenly image of Palestine in Western literature did not escape Edward Said, especially regarding its presentation as a dream. In his seminal book Orientalism, Said introduces his groundbreaking concept by stating that “Orientalism is the discipline by which the Orient was (and is) approached systematically, as a topic of learning, discovery, and practice. But in addition, I have been using the word “Orientalism” to designate that collection of dreams, images, and vocabularies available to anyone who has tried to talk about what lies East of the dividing line”9. Said’s incorporation of the element of dreams within the definition of orientalism is very telling regarding the ethereal existence of Palestine in the Zionist and other Western imaginaries. Palestine is made ethereal in their collective imaginaries through being presented as inaccessible, uninhabited, mystical, delicate, heavenly, and, above all, abstract, like a dream.

This unabashed prioritization of the utopic image over physical space is so ingrained in the Zionist ideology and in Western orientalism that violent and life-severing means are often used in attempting to materialize this imagined utopia of Palestine.

Yet, despite the abstract nature of the dream space, the colonizers have always been terrified of its potency, especially within the colonized minds. In his book, Ruling Minds: Psychology in the British Empire, Erik Linstrum delves into the excessive effort that was employed by the colonizing British empire to ‘rule’ the dreams of the colonized peoples in order to quell potential anticolonial rebellions. British psychologists and sociologists were dispatched to colonized countries so as to nip in the bud the “psychological origins of anticolonial movements”10 through infiltrating the collective dream spaces of the colonized with the tools of psychiatry, all with the aim of addressing British anxiety towards the “native mind”11. The book records how the British employed psychological tools to ‘measure’ the impetus and desire for rebellions against them by studying and recording the dreams of the colonized. A ludicrous tool that they invented, made of a roll of paper and a makeshift revolving stick with an inked top called the ‘Tremor Meter’ would ‘measure’ “fear among British soldiers fighting insurgents in Palestine”12.

Thus, the dream space, despite its ethereal nature, becomes a space of contestation; a space in which our collective Palestine and their utopic image of what it should look like are eternally colliding. This translates to the colonizers’ privileging of an imagined serenity associated with Palestine’s utopic potential over the real lived experiences of the people of the land in the ‘real’, material sphere. This unabashed prioritization of the utopic image over physical space is so ingrained in the Zionist ideology and in Western orientalism that violent and life-severing means are often used in attempting to materialize this imagined utopia of Palestine. Despite the ongoing Israeli occupation of Palestine and the myriad atrocities, it commits against the Palestinians in trying to efface them and the settler-colonial nature of this necropolitical desire13, a fascinating and very telling paradox lies in Zionism’s approach to nature.

That is, despite the Orientalist and Zionist dreams of Palestine, the land onto which those dreams are projected fights against the romantic, albeit fatal, utopic images. The foreign, invasive, non-indigenous trees that settlers plant in Palestine in the hopes that the landscape would slowly start looking more and more like their cities of origin, thereby materializing their orientalist dreams, catch fire. The land does not accept the roots of invasive trees growing into its womb, gnawing at its essence, and so the trees burn by existing14. This manifestation of the agency and the potency of the Palestinian land is implicitly understood as a form of solidarity with the people of the land against the Zionist dream. Instead, the trees of Palestine move in response to the summer breeze in ways as if to communicate something which the settlers, despite their obsessive documentation, cannot seem to grasp. The trees, even the martyred olive trees, thousands of which are uprooted every year by the occupation, sway gently, telepathically communicating with the people of the land. This agency of the land, exemplified in the intentionality and agency of the trees, exceeds and ridicules the utopic settlers’ image that fails to materialize.

Kamal Boullata, a renowned Palestinian artist, writer, and art critic, describes, referencing an Israeli artist, how the settlers “would look”, records Elias Newman, “upon the transparent blue skies and barren hills of Palestine, and dream of the cultivated green fields of Normandy and its clouded grey skies”. The early Zionist painters felt challenged by its exotic landscape.”15 Boullata communicates to us the settlers’ inability to literally see the land. The landscape of Palestine is so foreign to them that they would have to sublimate the real physicality of their surroundings with an ideal image of Europe in what seems to be a practice of acute denial. Their attempt to force Europe into Palestine is understood as an attempt to mimic European settings in the indigenous topography of Palestine. And so, early Zionist settlers would simply paint the trees as stiff, lifeless figures, as they had done in Europe, instead of living among and revering them.

The landscape of Palestine is so foreign to them that they would have to sublimate the real physicality of their surroundings with an ideal image of Europe in what seems to be a practice of acute denial.

Boullata also points, subtly, to what made Palestine a hotbed for Western imaginaries: the pleasant weather, specifically the sun and the life it gives. Palestine, known for its sunny days, its sweet summer night breeze, its natural landscape rich with serene olive and orange trees, its rivers, and its mountains, is the diametrical foil of European countries. Be it London, Frankfurt, Copenhagen, or Amsterdam, the European city is gloomy, depressive, and languid with perennial rain, cold atmosphere, lack of sunlight, as well as its “grey clouded skies” and “dark Satanic mills”. And so, Palestine emerges as a little piece of exotic heaven that not only escapes the glum European ambiance, but one where the exotic dreams of the Europeans, specifically the Zionist settlers, come into fruition; thus, making space for them to practice Bachelard’s “poetic space” on stolen land, in looted homes, and above Palestinian corpses.

Boullata’s words gently resound as I stroll through the forests of Marburg, where the famous brothers Grimm once lived. It is believed that Marburg’s gothic architecture, its tall, leery trees, its snaking rivers, and cobblestones are what inspired the fairy tales and their documentation. Yet, the European fairytale evokes a claustrophobia that pushes me to flee towards Marburg’s industrial sister, Frankfurt. The foil of Marburg, or what, to me, is the space that truly evokes a sense of benign fairytale dreaminess exists in a picture of al-Sāẖinah Spring in Palestine. Looking at the picture, a soothing impression of dewy space and benign solitude is evoked; indeed, a poetic space. The lightly cascading waters, the maternal, gregarious trees, and always, the abundance of sun, evoke an ethereal, eternal connection to Palestine. And so, the picture of the Palestinian spring becomes the very image of a dream of Palestine for the people of Palestine in the past and for the future.

The settler-colonial Zionist project may have, for now, occupied Palestine physically, but its failure to occupy the dream of Palestine in the Palestinians inside and outside of historic Palestine not only signifies a failure of the project as a whole but foreshadows a mammoth failure in the future of the necropolitical state. Every day, in the minds of every Palestinian, wherever they may be, the image of Palestine grows stronger and deeper into the quotidian details of their everyday life. Despite Zionist calls to simply ‘move on’ and be content with being killed, oppressed, or exiled as Palestinians, and despite the unconscionable price of refusing to forget, the dream of Palestine blossoms in every realm of Palestinian existence and materializes into action and agency. To this day, Palestinian writers, artists, lawyers, academics, service and labor workers, doctors, and scientists pass on this dream of a liberated Palestine to every generation so lovingly and tenaciously that 74 years after the Nakbah, I still dream of Palestine.