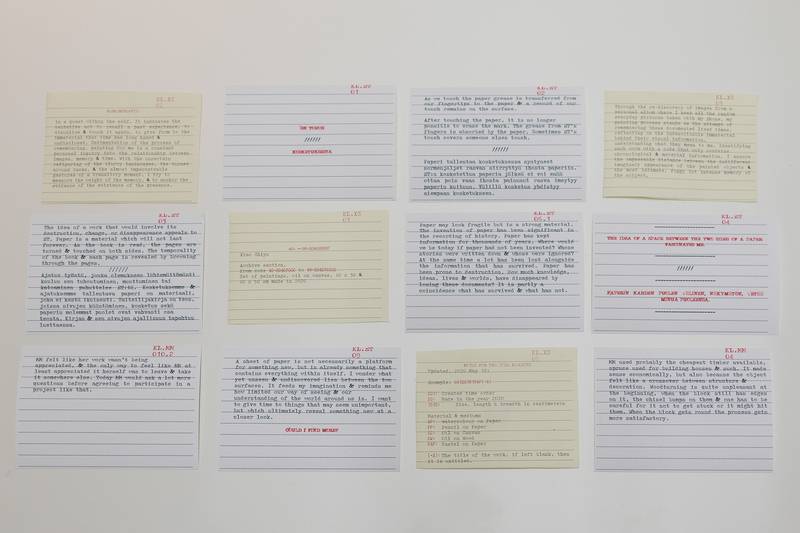

Installation view: Index Cards, is an experimental curatorial intervention to facilitate the transmission of knowledge.

Ali Akbar Mehta (b. 1983, IN/FI) is a Transmedia artist, curator, researcher and writer. Through a research-based practice, he creates immersive cyber archives that map narratives of history, memory, and identity through a multifocal lens of violence, conflict, and trauma.

Library as Archive as Excavation Site (an exhibition review of Kirjasto/Library)

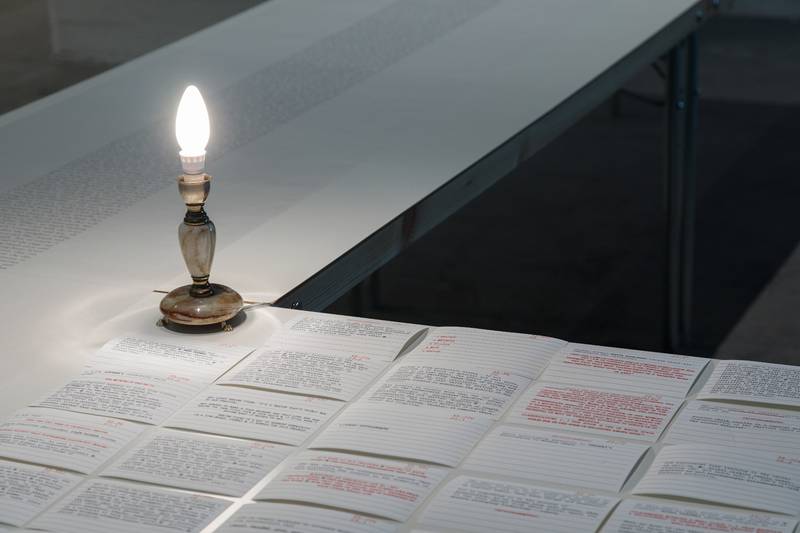

Walking into the gallery space of Forum Box during the exhibition Kirjasto/Library (11.12.2020 – 3.1.2021), one is greeted by multiple expanses of the processual and procedural – a methodically arranged exhibition sections drawings, a grid of paintings, imprints, technical metadata, index cards of conversations, logs, videos, scrolls of automatic writing, soundscapes, as well as collected and found objects (both revealed and hidden).

Installation view, Kirjasto/Library, Forum Box, Helsinki, 2020

Installation view, Kirjasto/Library, Forum Box, Helsinki, 2020

Installation view, Kirjasto/Library, Forum Box, Helsinki, 2020

The mood of the exhibition is ‘minimal soft punk’: naturally grunge brick walls of Gallery Forum Box offset the minimal interventions of tables and other structural elements and accentuate the DIY aesthetic of the exhibition. The exhibition is curated by Jonni Korhonen, Lin Chih Tung, Noora Lehtovuori and Ria Andrews, a recently formed curatorial team. During a conversation with the curators, Lin clarifies that the team is essentially a formalisation of friendship, “We formed this working relationship because of the Praxis [Master’s] programme [in Exhibition Studies in University of the Arts Helsinki], who worked previously for the ‘Surrender?Surrender’1 exhibition: we found ways of working together, familiarizing ourselves with how each of us works, forming new insights, and we didn’t kill each other in the end, so we knew that it’s definitely possible to work with each other, not just as a collective but definitely as friends, peers, or colleagues.

Kirjasto/Library poses several questions, two of which headline its curatorial note, asking “What is the state in which an artwork continues to exist after its finalization, after the last stroke, last edit, last rehearsal, last dot has been laid down? What happens to it when it is left unfinished?”

These questions related to the afterlife of the ‘artwork’ once it leaves the controlled space of the artist and their studio, and ‘when is an artwork complete’, may be old, but are entangled with the changing notions art, object, and practice. One may find several contexts for a response (to this question) within realms of the curatorial, viewership, the (gallery-auction) market, the collector, and the investor, among others. Museums may dedicate large resources to this notion of care, often up to 21% of sizable budgets towards restoration, storage, and creating optimum conditions for collection maintenance. Artist-run initiatives, on the other hand, are forced (or liberated) to address the questions and needs of care differently. For example, a space like Taidekirppis, an artist project that began in 2020, deals with this question of aftercare by first naming and filling a large void where artists, who after having created and/or exhibited works, and who may be without the means to maintain or store it, are offered a ‘no cost’ space over extended periods of time.

Kirjasto/Library (I classify it as an artistic/curatorial initiative for the purpose of this argument, rather than simply an exhibition) is a proposal where this question of care is responded to through the discovery of different ways/rituals of viewership and audience experience. Here the chosen medium is a constructed archive, consisting of dialogues with artists and submitted works, accessed through the gaze of the curatorial team. Essentially operating as a sensemaking apparatus, the exhibition seeks to collate different forms of ‘naturally forming archives’: materials that accumulate through the performative and non-performative gestures of artists, whether within the specific settings of their working environments, studios, or within various sites of living. Jonni adds, “we were curious of what is the reality in which their working exists in that sphere, not just as individual pieces but as the way in which they work. We wondered what happens when those systems of archiving are invited to be brought to the forefront, and especially what happens when the parts of those archives that had become more inert were pushed to velocity again. This led us to invite particular pieces in storage, works that artists themselves had moved on from, or that they had never found a place or manner to exhibit, ones lying dormant or that were in a form of incompletion. We wanted to play around with this part of archival action, this push and pull of existing and not-existing, all the while showcasing the labour that these actions demand from the artists.”

And so, the exhibition comprises of works by Anna-Maria Saar (AMS), Emilia Tanner (ET), Felix Klee (FK), Jérémie Wenger (JW), Joe Keys & Lena Schwingshandl (JK & LS), Minna Miettilä (MM), Natasha Faye Jensen (NFJ), Rea-Liina Brunou (RLB), Xiao Zhiyu (XZ): 9 artists culled from 125 applications. This then is the first question for the archive: who is included, and by implication, who is excluded?

Noora and Lin discuss their process of the open call and the subsequent selection process: “of course we were aware of the pros-and-cons of an open call, but after ‘Surrender?Surrender’ Exhibition where we worked with nine artists whom we knew, we wanted to reach out to more people. Despite the timeline that we had (approximately six months to set up the entire exhibition), we invested a lot of time in the planning of the open call, contextualising our ideas and thinking of what kind of information is to be provided to people. It was a new thing for us. We sent out the call via the school emails, universities and academies in Finland and internationally, and social media groups. Ultimately we received 125 entries and given the limited timeframe, we made selections based on some fundamental criteria while keeping space for individual selections”. Elaborating on the fundamental criteria that were established, Lin says: “We provided a very broad concept coining some terms like, index and archive, and asked applicants to make a proposal. We made selections based on whether their proposals were cohesive to this concept and whether there was room for manoeuvring and potential for the curator-artist to work together. Additionally, to make selections in a realistic situation. Keeping in mind the restrictions due to COVID-19 and the regulations on travelling, transport, and working conditions, we had to further reduce the number of works that could be included. We had some practical criteria like geographical distance, or of accepting existing projects, or preferring younger or upcoming artists as opposed to established artists.” So the common ground included the question of ‘who needs this?’

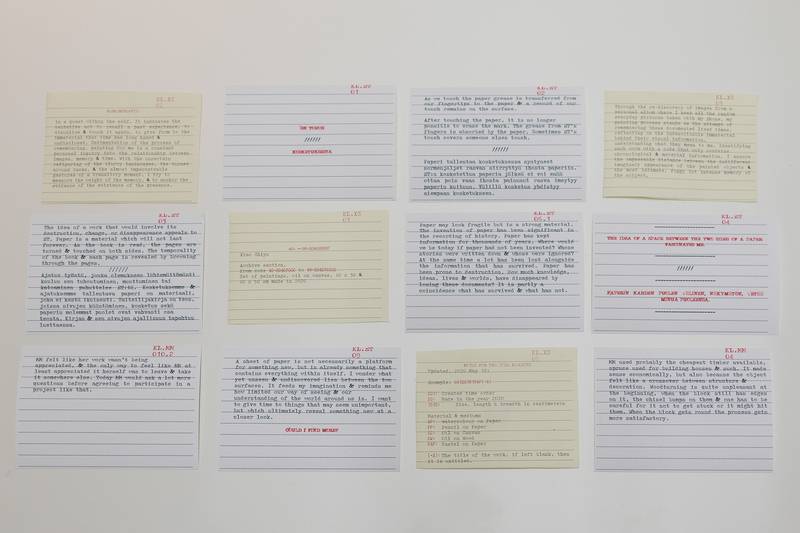

Although the exhibition text and conceptual framework fronts the curatorial teams’ interests of ‘possibilities that the group dynamics bring to the creative process and curatorial work’, their approach is sensitive and soft, and the exhibition focuses on mutual support and collaborating with the artworks to respond to the thematic questions rather than becoming fodder for a curatorial inquiry, which is unfortunately too often the case. Each work here is accompanied by a set of ‘Index cards’. As a central trope, it is the underlying thread that runs through the entire exhibition as performative dialogues between the curators and individual artists. These Index cards, based on guided questions and a range of freely submitted information by the artists, placed neatly in grids alongside each artists’ works, seek to provide insights into the material processes, ‘a closeup depiction of the artists’ thoughts on their practice, their works, their core values, anecdote[s] related to the process of making and more.’ Lin and Noora describe accessing the Index Cards to navigate the exhibition as “ritualising the process of searching”, similar to as if in the sacralised settings of a library.

As a response to the curatorial desires to make the audience or ‘guest’ to become an active participant rather than a passive viewer, these Index Cards direct us to become an excavator of the archive. As an excavation site then, the exhibition alludes to meanings that, like artefacts, are required to be dug up, discovered, studied. The exhibition ‘as an archive’ is positioned as a site pregnant with hidden knowledge, and a proposal is made for the exhibition site to be an active site of inquiry. This proposal is interesting because it puts forward a promise of a kind of exhibition-making that decentralises given information as the only knowledge and instead invites a ‘spending of time’ (a useful analogy in today’s ‘Attention Economy’ where viewers’ attention itself is monetised and therefore a commodity made scarce through capitalist modes of operations), within the parameters of freely shared knowledge. For me, the Index Cards is a sublime method, reproducible in its simplicity and ease, to provide an engaged viewership in an exhibition that challenges its audience rather than spoon-feed them. As a tool for deconstruction, it offers a much desired ‘vertical’ depth of knowledge and engagement, rather than the usual ‘horizontal’ variety (of artist quantity).

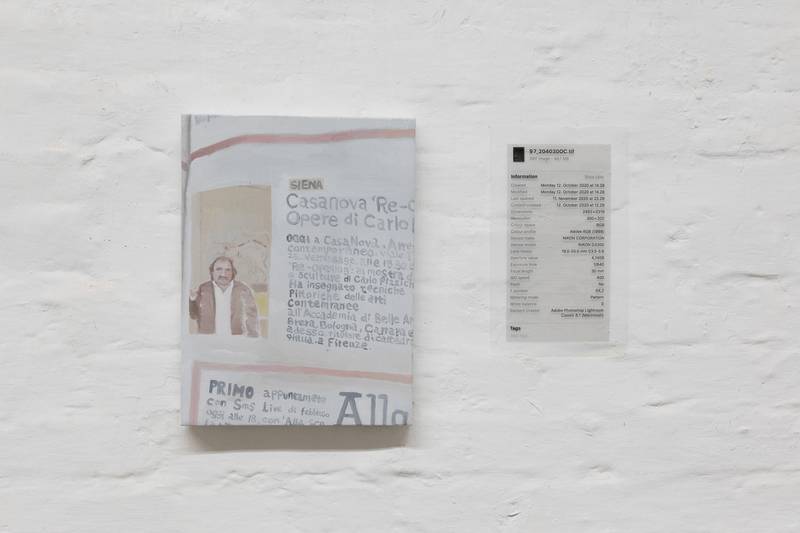

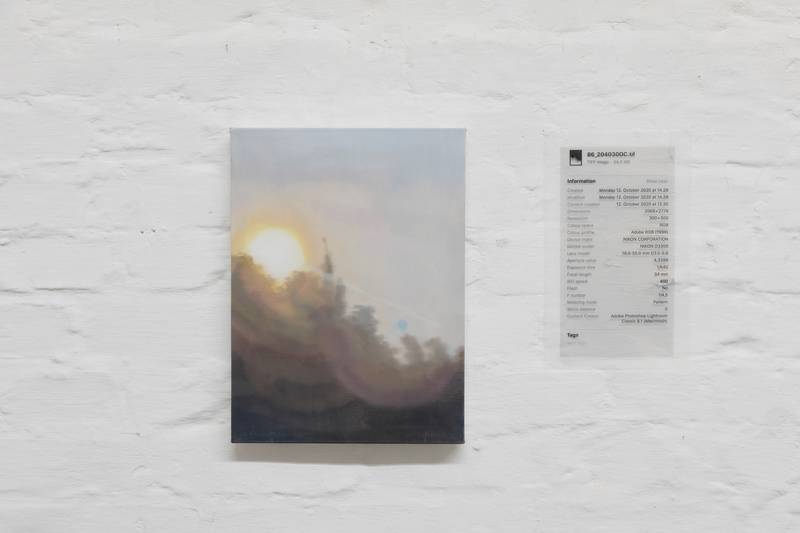

Xiao Zhiyu, 97_204030OC, 2020

Xiao Zhiyu, 86_204030OC, 2020

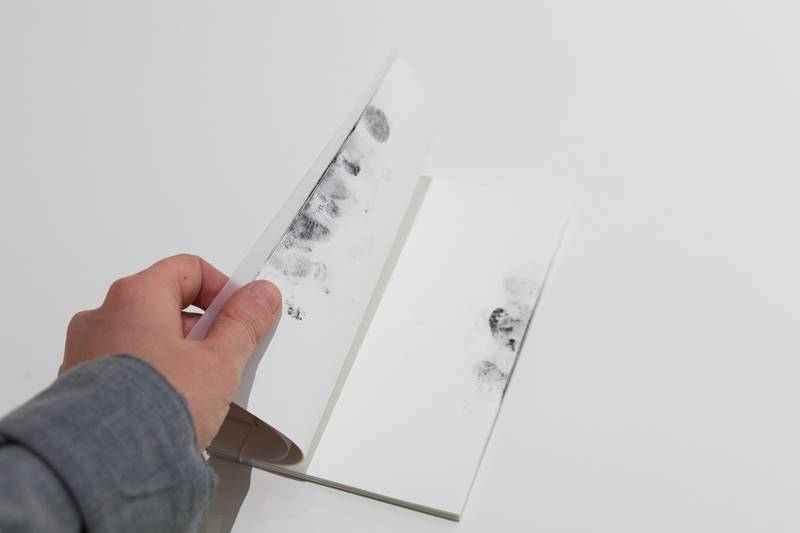

XZ’s works, the first you will see if you, like me, are a moth drawn to large brightly lit rooms, have a penchant for paintings and happen to look to the right as you enter, are a series of oil on canvas paintings based on photographs that are individually untitled except encoded through the default digitally-created filenames, and are accompanied by metadata describing a digital footprint of its source image. Placed nearby are MM’s and ET’s works, artists’ books with fingerprints capturing movements as a hand flips through a book; or body imprints, both hinting towards haptic residues and tactile interactions of skin-on-material.

Emilia Tanner, Browsings, 2016

Emilia Tanner, Browsings, 2016

To make visible the detritus, or otherwise discarded information, and to place it alongside and on an equal footing to the ‘work’, or to make it the subject of inquiry is to centralise the materiality of that which is a significant part a post-internet2 artist’s working practice, but is often hidden, kept secret, or considered insignificant. In one of the several Index Cards, ET talks of the durability of paper as a material but also as a historical artefact of documentation, asking what has been written, what ignored, and what has been lost?

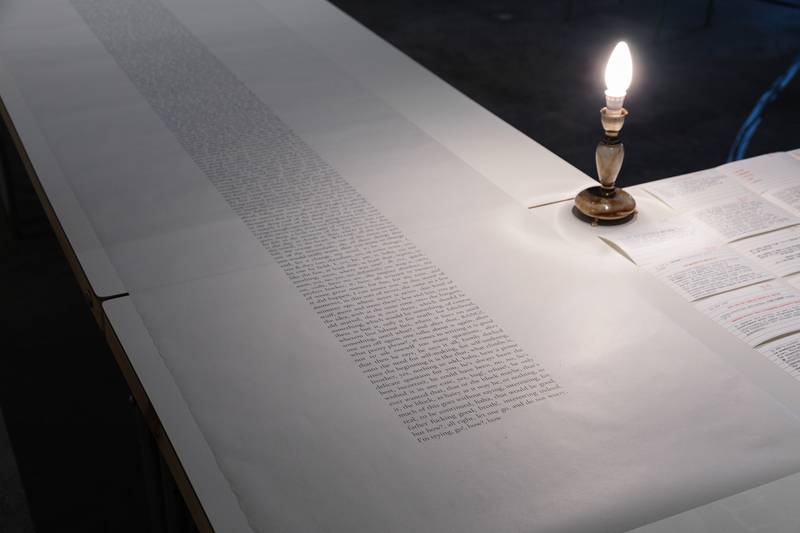

Jérémie Wenger, Artificial It, 2018

Natasha Faye Jenson, 1850, 2020; Felix Klee, it remains what it is, 2020

In the other side of the space, as a second set, JW’s works appear as large scrolls of texts co-written with neural networks, paired with a screen on which several video works play out on a loop. Three videos, one by NFJ and two by FK play out successively one after the other. At first, it is difficult to differentiate between the three, but slowly the distinct styles and thematics of the video begin to appear. Through historical archives and histories of classification, NFJ is examining the garden as an active site of power, human agency over dehumanised subjects, non-human and non-living ecologies. In ‘Stoop Labour’, one of the videos by FK makes comparisons through a two-channel video, between migrant labour, possibly illegal border crossings, and video game representations of illegal immigrants. It is unclear whether through this comparative viewing the artist hopes to make apparent the disparity between reality and representation, bring to our attention the faultlines of representative media and marginalised groups, or to enforce them. It is disturbing that although this work is the only one making any socio-political reference to the state of our world, it isn’t able to put forward a clear political position of the artist, the curators or the exhibition.

Joe Keys and Lena Schwingshandl, Contented, 2020

Rea-Liina Brunou, Sea Cucumber, rediscovered, 2015 and 2020

In the third section of the exhibition, seemingly more object-oriented, are placed works by JK & LS, an installation of various containers of mix media objects, a media-sculpture by RLB, and an old corrugated cardboard box as a container of other artefacts by AMS. Here, objects stand-in for a range of complications that problematise existing notions of both ‘archive’ and ‘library’. For JK & LS, the installation of objects and containers represent the artefacts shared/collected as a dialogue and a method to manifest a developing friendship. These objects and containers (boxes, bottles, plastic cases, etc.) betray a longing for physical or ‘tactile’ objects instead of images sent via. digital devices, pointing to the generally present and increasing discomfort with relying on digital interaction as a primary mode of social interaction. And yet, it also points towards the questions of how ‘real’ is reality or the hierarchical position of digital as opposed to its AFK3 counterpart. In the larger conversations of the archive and media theory, the antagonistic relationships between the digital and analogue, physical and virtual, are interchanged, made fuzzy.

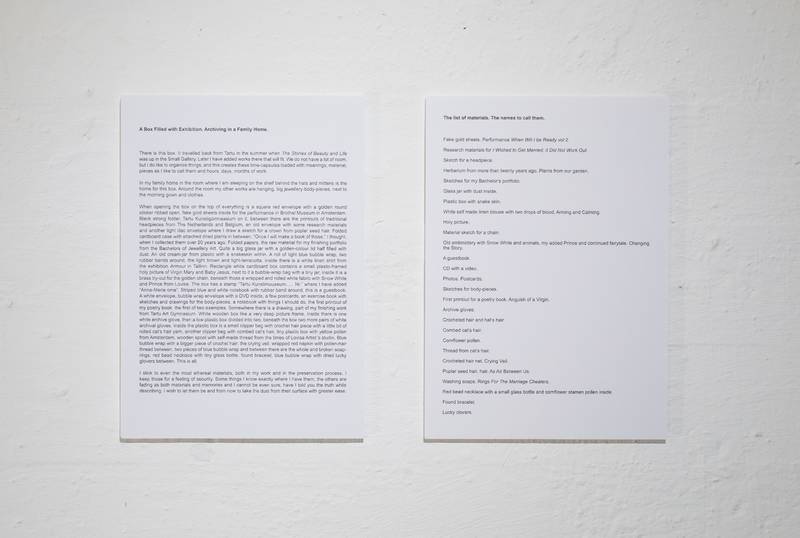

Anna Maria Saar, Archiving at family home, 1996-2017

Anna Maria Saar, Archiving at family home, 1996-2017

The work by AMS titled ‘Archiving at family home’, described as ‘materialised moments, documents of life’, is a sealed box and an artist note that assures the viewers of its contents: Fake gold sheets, research materials, sketches, glass jars, plastic bottles, pictures, books, CDs, pieces of hair, pollen, soaps, found objects. This list, as data and as a promise of the authenticity of the box’s contents (the box remains sealed throughout the exhibition), is accompanied by another text that weaves the material contents into a storied narrative, where we are invited to imagine the shapes, colours, textures, and smells of the contents. Both works by JK & LS, and by AMS, cement the nature of the objects as ‘personal’. In doing so, they put forward a proposition that questions the notion of ‘value’ that is central to the investigation of archival praxis. What criteria can archives present themselves to be accountable for the shifting notions of value: what is valuable? And to whom? How to create a space for common value? What space exists for artefacts of personal value? Does it matter?

Installation view, Joe Keys and Lena Schwingshandl, Contented, 2020

The ideal and idea of the archive (and by extension the archivist) have become virtually unrecognisable from its early 20th century constructs, as questions of elucidation and clarity have been debated both in the journals of archival science, as well as outside of them. The archive, we might say, affords access to the past in the present and in so doing shapes futures. The contribution of archives in the ‘development of society’ is recognised and foregrounded by international agencies such as UNESCO. The definition of archival value articulated in the universal declaration on archives adopted by the International Council on Archives and endorsed by UNESCO in 2011 reads:

Archives record decisions, actions and memories. Archives are a unique and irreplaceable heritage passed from one generation to another. Archives are managed from creation to preserve their value and meaning. They are authoritative sources of information underpinning accountable and transparent administrative actions. They play an essential role in the development of societies by safeguarding and contributing to individual and community memory. Open access to archives enriches our knowledge of human society, promotes democracy, protects citizens’ rights and enhances the quality of life.4

Archives are the documentary by-product of human activity retained for their long-term value. They are contemporary records created by individuals and organisations as they go about their business and therefore provide a direct window on past events. They can come in a wide range of formats including written, photographic, moving image, sound, digital and analogue. Archives are held by public and private institutions and individuals around the world.5

There is nothing original in the claim that the appraisal function (or evaluation) forms the core of the archival discipline, but the notion of appraisal, of selection by the archivist, and the role of archives remain an essentially contested ground. If the exhibition as an archive is to be seen as an apparatus that organises or classifies the works into a system (and archives, in their traditional canonical sense, are burdened with the historical heritage of administrative power), then it is important to view this questioning as a significant departure from archival canon. Archives have traditionally worked in conjunction with the same principles that govern museums – they have been petrification machines – collecting, encoding and storing, objects, documents and data, cultural or otherwise, that has been deemed ‘valuable’ by the agency of the archival system. According to Achille Mbembe, archives are ‘not a piece of data, but a status’. Instead, artistic practices have forced a change in how archives may be read, looked, used, and even produced – against the grain. Counter Archives, or specifically archives as an artistic practice, have often sought to disrupt the power matrix of the archival canon, often employing the same strategies and tools of the institutional archive, to counter it.

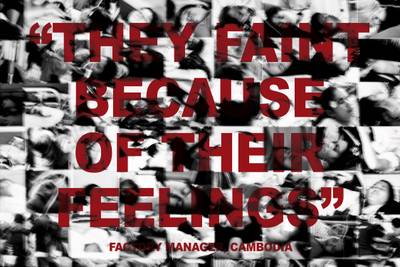

Installation view: Index Cards, is an experimental curatorial intervention to facilitate the transmission of knowledge.

Another distinction between practices within the realm of archival canon and those of archiving within artistic praxis would be the relationship of archives towards digital tools and organisation systems. Where archives such as the Finnish Archives are following the wake of other international agencies to digitise their collections, artists have been working with an increasing distrust of the digital. On the one hand, this distrust is understandable, with the complex relation of human beings with biopolitical corporatised nature of data today, opaque practices of data -mining, -farming, nonconsensual lifelogs6, and ‘bad data’7 generation. On the other hand, it reveals an artistic fetish for old media. Claire Bishop describes a sudden attraction of “old media” for contemporary artists in the late 1990s that coincided with the rise of “new media,” particularly the introduction of the DVD in 1997. Overnight, VHS became obsolete, rendering its own aesthetic and projection equipment open to nostalgic reuse, but the older technology of celluloid was and remains the favourite. Today, film’s soft warmth feels intimate compared with the cold, hard digital image, with its excess of visual information (where each still image contains far more detail than the human eye could ever need). Artists stake their attachment to celluloid (and other old media) as fidelity to history, to craft, to the physicality of the editing process; the passing of real film as a loss to be mourned – its desirability inextricably linked to its market value, of being scarce, rare, precious. To maintain the cultural integrity of the reused artefact books, performances, films, and modernist design, objects are incorporated into new works of art and repurposed.

Hal Foster’s 2004 essay, ‘An Archival Impulse’ defined archival art as a genre that “make[s] historical information, often lost or displaced, physically present. To this end [archival artists] elaborate on the found image, object, and favour the installation format.”8 Whether this happens in the form of projects dealing with real archival material or artworks in which artists use the archive as a theme – sometimes even inventing material – the idea of the archive continues to be an undeniable force and organising structure in praxis today. Where Hal Foster describes archives as (artistic and/or curatorial) ‘practice that push the postmodernist complications of originality and authorship to an extreme’, Derrida challenges attempts to compound arkhé and archive, exposing the way in which the concept of the archive is inescapably linked to Archontic power. He reminds us that archives are monuments, in the way in which power is reconfigured. It not merely stores and includes, but also testifies to a narrative of exclusion – what is included in the archive is due to its value, that which is excluded loses its value. But the question is, who ascribes this value to objects or documents in archives? And through what criteria? And so it makes sense that Achille Mbembe describes archives as a “status symbol”9. Despite this, the role of archives has been to ensure ‘objective’ institutional accountability.

Meanwhile, we have learned to call the tape-recordings of another generation, ‘vintage’ photographs and film footage of textile mills, dilapidated bottle factories, urban ruin, and other signifiers of the industrial era; home videos, souvenirs, little bits & pieces of memorabilia, postcards and photocopies of a ration book; and our own drawings of how we imagine the *** factory to have been, between the purgatory of a time once in memory and now forgotten – an ‘Archive’. Perhaps it is time to shed the fetish for old media, and understand our own complicity in the perpetuating of the same systems and hegemonic orders we want to shed and abolish – What we need is a newer kind of an archive, or at least a re-imagination of what archives can mean: is it possible that archives are not only petrification machines, not only concerned with the idea of memory, of the old – but also concerned with the idea of the future, of imagination? Can archives now work within the parameters of today’s knowledge society? What do archives – conceptually integrated into praxis, whether towards artistic research or declared as a work by itself, an active process – look like? How can they not be a passive matrix through which content passes but a body of work that shapes the entailed content?

Kirjasto/ Library does not formally announce a thematic drive at its outset, but situates itself within an abstract idea ‘archiving’, or of what a collection, library, or an archive could be. For example, the main difference in approach between libraries and archives is that libraries are meant to be accessed by its public, where archives are traditionally designed for preservation, sometimes even keeping its artefacts out of public reach. An archive is furthermore an intrinsic networked system of metadata that may link its artefacts into a cohesive system of retrieval. A library may use an archival system (alphabetic or chronological, or a system of subject-wise distribution, among others) for its organisation, but isn’t an archive per se. Of course, these notions of etymological differences and terminology are exactly what makes artistic interventions and an exhibition like this interesting, because it questions how to achieve a synergetic balance between preservation and transmission, once knowledge has been produced? Who takes charge of this and how?

“In a library, you can borrow things and take them home, you can move [parts of a collection], in our exhibition, it wasn’t possible. Like in an archive, you were able to browse, you were able to experience, but you weren’t able to take, or return things”, Noora clarifies, while also maintaining that this could have been a model under different conditions, “and yet, in some like the British Library, you can be in the space with the books, but not take them out.”

Despite not committing itself to articulating the possibilities of how exhibition-making may benefit from the methodologies of archival or library structures, the exhibition curators utilise these same methodologies to focus and seep into multiple frameworks and discourses: of dialogue, relationality, power, and systems theories, etymologies of organisation and reality-making as a canon in flux. “Though it was not our mission with this particular exhibition present strategies of combating these difficulties”, says Jonni, “I do feel that our vision of seeking to find ways to present not just artistic archive, but also an archive of artistic work made visible, the actual manners in which artists maintain and trace their labour into the artefacts they construct, both in a practical sense and in an abstract sense, has the effect of highlighting the lived-in-ness of art and the labour of producing it.” In this sense, the exhibition doesn’t focus on investigating archival structures but uses existing methodologies of ‘archiving within art praxes’ as a guiding force.

And so, it was exciting for me to read, that ‘[t]o construct an archive is to construct a continually activated value- and meaning-making machinery’. Definitely, an archive is a complex network of information organised as a system and potentially can provide long durational and continuous engagement to unpack its rhizomatic layers of meaning. No doubt, many layers of relationalities between works (as objects and subjects of inquiry) or between individual artists’ thought processes and core values can exist, or emerge, at any given time, between any given set of artists, but why these artists or these works are placed together, either as an archive or as a library is, on the whole, insignificant. “Perhaps there are sheep and goats, and these are examples from the sheepfold. But in this context, we want to remember Walter Benjamin trenchant remark ‘Every document of civilization is at the same time a document of barbarism’. The point is that all our documents are always multiply coded and that scholarship preserves and studies the multiple meanings”10. For the curators as well, “The functioning of an archive, be it then a physical location, a collection of virtual information, a classification, or something else, is by nature a construction of a canon. This being a very broad term, to offer one definition here, what I am talking about as a canon is a form of reality-making. There are actions of denying, tiering, classifying, ordering value, that being assigning real-ness, involved in the process of constructing an archive”.

Detail view: Joe Keys and Lena Schwingshandl, Contented, 2020

What Kirjasto/Library as an exhibition does, is that it provides a much-needed impetus for conversations about why archive-based artistic practices, or archive-based exhibition-making practices, are required. Archives are important because we now live in a time that may be defined as ‘archival time’11. According to German theorist Wolfgang Ernst, “the archive has no narrative memory, only a calculating one”12 and in this sense, one may read the archive as not being dedicated to memory but to the purely technical practice of data storage, where any story we add to the archive (here a Topous Outopous, a ‘placeless place’ – a prime paradox, or a breach in timespace) comes from outside (the archive). And yet, a distinction between ‘archiving’, as opposed to archives, is important: where archives may be a tool for memory, archiving here is an activation towards remembering, where ‘re-membering’ literally means bringing members together again.13

What it puts forward as practice, is the significance of a learning process within curatorial work. It has been refreshing to see, in evidence, the work done by the curatorial team to create a common ground of understanding, between themselves as well as with the invited artists, and to work in conjunction to create this exhibition. Exhibitions are, by definition, a singular unit or container of multitudes, whether it be several works by a single artist, or works by several artists, whether they be 9 or 125. Here, the exhibition provides an archival network of interconnected-ness (within, works, artists, curators, and ideas) that decentralises notions of what has traditionally been understood as ‘curatorial work’, and instead puts forward shared hopes of creating ways in working together to build up strategies of care and compassion, of support and friendship as being central.

Installation view: Index Cards, as a curatorial agent, foreground the commonalities between library and an archive within the exhibition, not just as depositories of knowledge and information, but from social spaces and sites of multiple engagements and workings where these traces of artistic labour become shared and shareable.

The curators have no current plans to conceptually take this exhibition forward, but hope that it will continue to exist in the future as memory in those who have experienced it, and as an impetus for imagination. They are also uncertain about the possibility of taking their method as a curatorial team forward. Lin says, “We are all studying and this exhibition has been a great learning experience, but we haven’t yet thought of continuing to work together”, where for Jonni “our goal with this project was experimentation, and we did have a very playful attitude towards that. We wanted to try out different ways of working and collaborating […]” and are “in the process of building up the ways in which we would like to continue our journeys as curators.” And yet, I for one look forward to more work from them as a team, as well as to see other works from the students of the Praxis program.