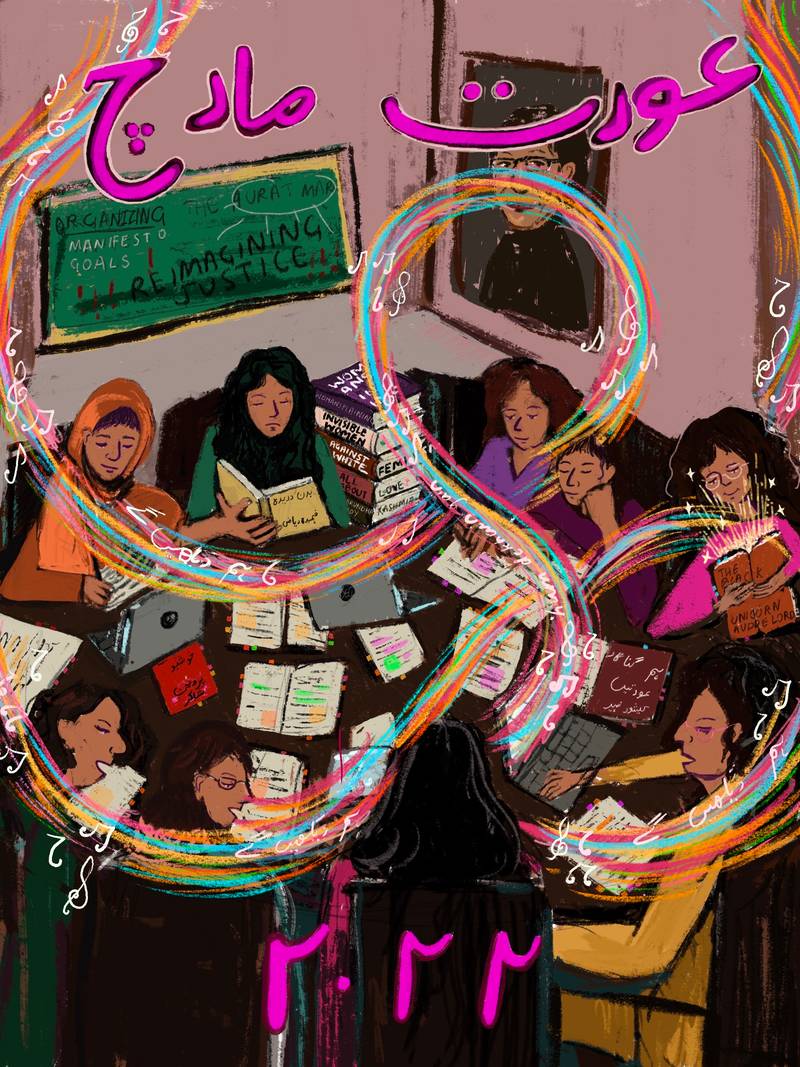

Illustration: Laiba Raja

Sheherazade Amin is a Pakistani advocate and activist. She completed her legal studies in the United Kingdom before moving back to Pakistan. “The Meesha Shafi” case was one of the first cases of her legal career. Her areas of expertise include but are not limited to defamation, death row inmates and sexual harassment cases. She is currently completing her LL.M in Intellectual Property Law from the University of California, Berkeley. Sheherazade also enjoys reading, writing poetry and playing the violin.

“The change we are seeking is not just institutional. We want to cultivate change in society and build a political platform where all women, trans people, and non-binary persons can feel a part of Pakistan. There needs to be an intersectional feminist movement, and we are here to make it happen.”1 — an Aurat March volunteer.

Seeping into the Islamic Republic of Pakistan quicker than anyone could have imagined, the #MeToo Movement rattled the nation to its core, leaving citizens to question beliefs they had been conditioned to hold dear. The movement started at the grassroots level, with students speaking out against the deadly debate culture in the country. Female speakers who had always been targeted and over-sexualised felt empowered to share their experiences. The movement travelled through society until it reached the crème de la crème, exposing the inequality and injustice lurking in the corridors of both public and private institutions.

The case that jump-started a broader public discourse regarding the movement was the Meesha Shafi Case2. Although earlier in April 2018, Mehravar Ali had already called out the country’s biggest music-streaming website, Patari’s CEO, Khalid Bajwa3, for sexual misconduct, it was Meesha Shafi’s case that set off revolutionary changes in legal precedent and legislation. This is because her alleged harasser was not only her colleague but one of the biggest names in South Asia, the singer-songwriter Ali Zafar. Although still awaiting a final judgement, Meesha’s case sparked the “infamous” Aurat March, a march happening every year in Pakistan on International Women’s Day (March 8) as of 2018.

The Aurat March was first held in Karachi on March 8, 2018, with the overarching theme of Equality. Although many women, children, and LGBTQ+ individuals came out and marched, banners held high; it wasn’t till 2019 when the March spread to other parts of the country and began to evolve into a safe space for the vulnerable populations of Pakistan. The feminist movement began to shatter the ever-looming socio-economic divide from the day it started. Initially, the movement only seemed to refer to the existing inequality between the positions of men and women in society-which was in contradiction to Article 25 of the Constitution4 — However, later it became much more than that. Equality took many shapes and broke the mould it had been enclosed in over the pre and post discourse of Aurat March 2018—not to be restricted to discussing equality of the two traditional sexes but also start discussions around various inequalities in the public-private spheres of society.

Aurat March has inevitably been subjected to extensive scrutiny as it has questioned a well-established power-sharing dynamic between state institutions and the patriarchy. The narrative that “Aurat March is misleading women” began as early as January 2018. It was then followed by “the movement is seeking to erase morality from society by allowing LGBTQ+ individuals to become active citizens of the state.”5 On the contrary, Aurat March uplifted many such individuals and gave them a safe space to thrive. Nisha Rao, Pakistan’s first transgender lawyer, is only one example.

In 2019, a popular sign read, “If Cynthia does it, she’s applauded. If I do it, I’m the villain.” This addressed the fact that white women were allowed “liberties” within the same state that oppressed brown-skinned women. Holding women of a fairer skin tone in higher esteem first emerged in colonial India, as white women were part of the British Raj and thus represented a higher socio-economic class.

Aurat March chapters flourished across the country despite the heavy backlash, and marches took place in cities like Lahore, Islamabad, Faisalabad, Multan, etc. The theme of the 2019 March, ‘Sisterhood and Solidarity’, brought out many allies and asked deeper questions such as, ‘why do women doubt other women more than their male counterparts when it comes to harassment claims?’ or, ‘why don’t women lift each other instead of competing with one another to please the patriarchy?’. Aurat March put forward the idea that women have always been divided so that patriarchy could maintain its power. By re-establishing sisterhood, women and other marginalised groups can hold the collective power to challenge patriarchy and its many institutions.

In 2019, a popular sign read, “If Cynthia does it, she’s applauded. If I do it, I’m the villain.” This addressed the fact that white women were allowed “liberties” within the same state that oppressed brown-skinned women. Holding women of a fairer skin tone in higher esteem first emerged in colonial India, as white women were part of the British Raj and thus represented a higher socio-economic class. Though this idea should have died with independence, it was inherited by post-colonial Pakistan, which still has matrimonial advertisements that read, “fair skin tone wanted.”6 That year, the Aurat March also served as an anti-war movement as the war hysteria grew between India and Pakistan in the days leading up to the March.

Aurat March has represented a safe space for many marginalised groups. The media has had to slowly and steadily include feminist activists and allies on its panels. The story of a wrongfully accused, mentally ill female death row inmate was brought to light in 2020 due to the efforts of Justice Project Pakistan7 in collaboration with Aurat March. Her release was the focus of many chants at Aurat March 2020 and 20218. Aurat March also allowed her case study to be read aloud to all marchers and requested that they advocate for her release. It resulted in a landmark decision regarding mentally ill individuals by the country’s highest court, the Supreme Court9. Barrister Sarah Belal, a March ally and the case’s legal representative, stated that the March’s advocacy helped Kanizan Bibi10 gain justice. In Aurat March, many female artists have found avenues for fully expressing themselves. Aurat March Lahore occupied the streets by putting up artwork for the Aurat March 2020. The artwork represented a diverse group of artists and different interpretations of what the march meant to them. The artwork was torn apart by a mob within hours.11 A petition was filed in the Lahore High Court by the Judicial Activism Council chairman, begging the court to stop the march, stating that it was “against the very norms of Islam.” The Chief Justice rejected the petition, emphasising that freedom of expression and assembly could not be banned12.

When the slogan “Mera Jism, Meri Marzi” (my body, my choice) was raised in the 2021 Aurat March to illustrate the demand for bodily autonomy and protest against gender-based violence13, it caused a furore as it was misconstrued to be a slogan demanding immorality. Since the very beginning, one of the demands in Aurat March’s manifesto has been the right of a woman over her own body. Through social media, literature and panel discussions, Aurat March has been advocating for the criminalisation of the practice of virginity tests. Progress was finally made when a petition was filed by Sadaf Aziz, Farida Shaheed, Farieha Aziz, Farah Zia, Sarah Zaman, Maliha Zia Lari, Dr Aisha Babar, and Zainab Husain. Their petition was clubbed together with another filed by a member of the National Assembly, Shaista Parvez Malik, with Sahar Zareen Bandial as lead counsel. The petition sought the abolishment of virginity tests (including the two-finger test and hymen examinations) and especially as part of an investigation of a claim of rape or sexual assault, as this practice was in violation of the Constitution of Pakistan. It further sought that the direct use of phrases such as “habituated to sex” and women being of “easy virtue” or “loose morals” be discontinued as part of the literature of medical reports issued by medico-legal officers in cases of rape and sexual assault. Finally, in January 2021, the practice of virginity tests was ruled to be criminal due to the efforts of Aurat March and other activists14.

The #MeToo cases brought forward regarding educational institutions, particularly in 2020, wouldn’t have been possible without the March. The Anti-Rape Ordinance of 2020, while flawed in several ways, was only enacted as a result of increasing pressure from women and the LGBTQ+ community, both online and in person. Earlier this year, due to the efforts of Aurat March, amendments to the Protection Against Harassment of Women in the Workplace Act of 2010 were finally introduced, and much-needed protection under the law was provided.

The 2021 Aurat March took place amidst a global pandemic. It focused on women’s health and the unequal medical treatment they most often received—the manifesto15 detailed actions such as the introduction of female and transgender medico-legal officers16. The Lahore Chapter specifically ensured that their 35- page manifesto emphasised their vision of a feminist healthcare system. Volunteers of the March also set up health camps across the city and continued to keep them functional well past the march. Many volunteers, marchers, and allies felt that one unquestionable outcome was pushing for more conversations, particularly about consent and bodily and sexual autonomy. The legislation takes time due to the amount of procedure required for its drafting and implementation, but providing a safe space for these issues to be discussed and public awareness to grow is a huge accomplishment in and of itself.

The 2022 Aurat March ‘Reimagining Justice’17 theme encourages the Pakistani society and the State to reimagine legal, economic, and environmental justice to align with a feminist future. It asks that a new and more inclusive perspective of justice be envisioned, expanding its definitions beyond the limited ones granted under the patriarchal system and its legislation. Radical reform of the justice system should be undertaken instead of superficial gender representation. There should be more women and gender minorities in policing and judicial strategies. The death penalty and chemical castration, traditional punishments in a patriarchal system, should not be considered viable solutions. Instead, there should be a radical shift to investing in preventative policies such as the educational sector, community building and social welfare schemes. These are just some of the visions of a justice system in a state with a feminist alignment.

The March has served to amplify so many voices. The #MeToo cases brought forward regarding educational institutions, particularly in 2020, wouldn’t have been possible without the March. The Anti-Rape Ordinance of 2020, while flawed in several ways, was only enacted as a result of increasing pressure from women and the LGBTQ+ community, both online and in person. Earlier this year, due to the efforts of Aurat March, amendments to the Protection Against Harassment of Women in the Workplace Act of 201018 were finally introduced, and much-needed protection under the law was provided.

Aurat March has given me more sense of belonging and protection than any government or institution. It is a movement that is not restricted to March 8 every year. It is a movement that remembers, mourns, and fights for justice for Qandeel Baloch’s19 brutal murder. It asks for Reimagining Justice when it comes to rape victims being charged with zina under the Offense of Zina (Enforcement of Hudood), where rape can only be proved with the witness of four adult males20, a standard that is practically impossible to achieve. In a state that fails its citizens - particularly those not Sunni Muslim men - movements like Aurat March make space for collective action.