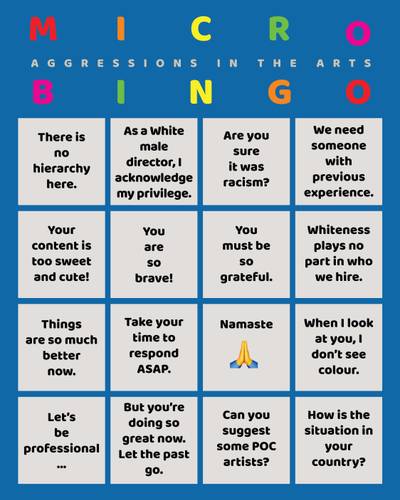

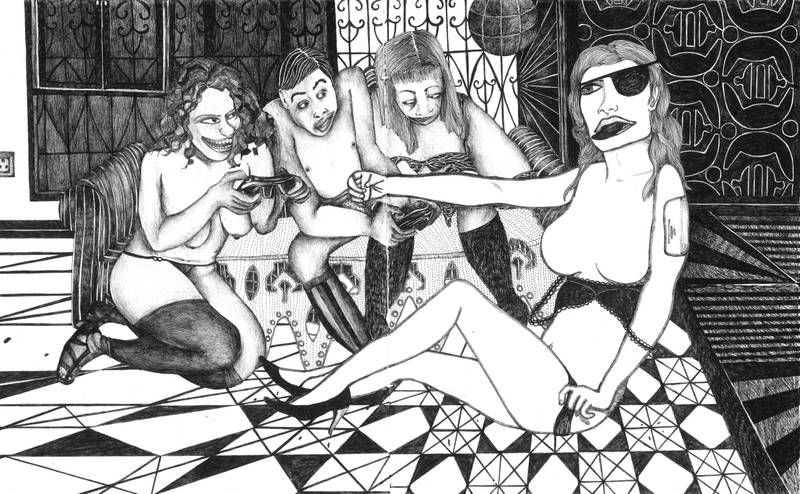

Drawing: Vidha Saumya

Elham Rahmati (b. 1989, Tehran) is a visual artist and curator based in Helsinki. She is the co-founder and co-editor of NO NIIN. In 2019 and 2020, she worked as the curator and producer of the Academy of Moving People & Images (AMPI), a film school in Helsinki for mobile people.

Vidha Saumya (b. 1984, Patna) is a Helsinki-based artist-poet. She is the co-founder and co-editor of NO NIIN – an online monthly magazine in Finland, and a founding member of the Museum of Impossible Forms – an award-winning cultural para-institution in Kontula, Finland.

The Noble Pursuit of Promoting That Which Is Not Mine

Elham Rahmati

Every once in a few days, I come across a stunt pulled by an artist that makes me sigh and repeat, I hate contemporary art. I’m certain I’m not alone in my temporary, but all too often, moments of disdain for what I seem to have dedicated my work-life to. I’ll give you a couple of examples:

A while ago, there was a social media campaign among Iranians on social media against capital punishment. As I was scrolling through IG, I noticed an incessant number of posts published from the account of an artist I knew. The posts were photo documentation of a performance he had done some time ago about the same topic. He stands on a bloody platform in the performance, his eyes covered with a rope hanging from the ceiling around his neck. The work, ridiculous in its overly literal representation of the issue, wasn’t what made me unfollow the artist and then bitch about him for hours. What made me spiral was that he kept posting reshares of others praising his work, courage, sense of justice, etc. He had swiftly moved from promoting the cause through his art to promoting his art through the cause, joining the many artists who seem to be lost while navigating the fine line between the two.

Again on social media—where I seem to get most of my observations—I came across something even more obnoxious. An artist acquaintance of mine had made a post about a friend who had recently passed away. The post went something like this: “I’m so heartbroken about the news of my friend’s passing,” followed by “Here is the link to a stellar review my friend has written about my work.” Is this how artists are mourning now? Oh, my friend is gone, but look at how much they liked my work, how amazing they thought I was. Maybe mourn for a minute before promoting yourself, will you? If I was his friend, I’d be haunting him for some time. How dare you use my untimely death to promote your mediocre art?

Don’t get me wrong; I am a firm advocate of artists shamelessly promoting themselves through whatever personal platforms are at their disposal. It’s not every day that we receive the recognition we feel our work deserves. If we don’t acknowledge and promote our own labour, who will? We all have to do what we can to survive in these cutthroat art scenes. Many of our contributors in NO NIIN are those whose work we have spotted through social media, and I’m grateful for their generosity in showing their works for free on a public platform.

As artists, we often have a sad tendency to be a bit self-absorbed and make everything about us. Most of the time, it’s harmless, but there are times when our actions make us symptoms of the unfeeling art and cultural scenes we live in, where the struggle is everything and every single value you hold dear is turned into a currency and later consumed by some miserable institution until all meaning is sucked out of it. We are taught to value competition and to embrace the hustle. And just maybe, if everything worked out, we’d make it. Isn’t that the capitalist wet dream?

Concurrent with the launch of NO NIIN’s first issue, an ongoing Open Call was launched, where we highly encouraged our readers to write to us and express their interest in writing a review for a specific upcoming exhibition/event/seminar in Finland. Or write to us if they have someone specific or a collective in mind who is active in the arts scene in Finland and whom they would like to interview. We’ve also published the rates of our payments to make sure our readers know we are not asking for volunteer work. One year later, we received maybe three or four submissions from artists interested in writing reviews of another artist’s work or having an interview with them. It’s been quite a disappointing revelation to us to see the art workers in this scene show such little active engagement with other artistic practices that are not theirs. What we’ve received plenty of is artists asking-in some instances, demanding-that we find someone to review their show, or have an interview with them, even if they themselves refuse to dedicate their time to doing the same for another artist.

I guess there are a few unsolicited pieces of advice that I’m trying to jampack into this little editorial: 1) Promote your work through your opinions, your values, your attitude and your integrity. 2) Promote the ideas and principles you advocate for in your work, not when they’re trending but when they’re not. 3) Care is a two-way street. It’s something we all deserve, so let’s make an effort to show it when we can, and if we don’t, it’s best we lay off expectations when it comes to our own needs. 4) Don’t make things that aren’t about you, about you, just don’t. I’m telling you, it’s a dick move, trust me.

Walk on eggshells or break eggs for omelette?

Having dignity, Being direct

Vidha Saumya

Directness is a desirable quality and very hard to possess, and not just for an artist, no need to nod yet, I have just started talking about directness and why it’s natural to feel like an imposter.

Eight years ago, I wrote an email to one of my employers, asking for a raise. I had listed all the extra work I was doing, how I was getting very little time to do my drawings, how it was taxing me physically, how I felt unacknowledged, blah blah blah, yada yada yada. I showed the letter to my friend, and she said if you’re writing this because you want a raise, at least write one sentence that says, ‘give me a raise in salary’. Right. Despite the resolve in my demand and the passion with which I worked, asking for something was too direct. I never sent that email.

Two years ago, I wrote another email to another employer, a friend, to point out that they had unfairly treated me in a situation and that I was disappointed in their lack of transparency. That email, too, still sits in my inbox. I could afford to do without the person, so why bother.

Thus, directness is a quality that is hard to possess and even more painful to process. Wise people say that ‘it will pass’ after you have gone through a difficult period, but how do you know for sure when every animate and inanimate being around you still hint that you are in their way? What if the difficulty never goes away? What if you will never be able to say what you’d really like to in the world of ‘direct’ messages and learn how to say ‘no’? Is there any possibility of dignity if you only continue to say ‘yes’ to everything?

It is difficult to define the shelf life of the aftermath when it comes to long-term abuse – insidious gaslighting and invisiblising contribution. In retrospect, one can only look with dismay at our horridly ‘normal’ reaction of adjusting, letting go, and making it all okay. Most of the time, we don’t even feel disappointed or enraged. We feel boredom and indifference – and operate with an attitude that would keep us from getting bitter. Amidst managing livelihoods, prioritising time for pleasure, self-belief, reflection, and building backup plans, honing directness, calling a spade a spade is a personal commitment and needs practice. With time, this commitment becomes a priority. How to shed the shell of politeness, stop weighing each word, and keep walking on eggshells? To eat omelette, we have to break eggs, they say.

Meanwhile, my resting bitch face has the following filter added to it:

An elegant smile that rouses confidence and delight.

Different genres of artistship acquire a unique relevance and significance in the rapidly changing socio-political climate, budget cuts, and growing precarity of the shifting status quo of academia and the art world. Indeed, there isn’t a single method to being an artist. The artist is publishing artist books, making protest signs; spending mornings to draw; their days at the day job, the second job, and another job; evenings are spent threading and treading new-found expectations while managing several side hustles while being signed up for community care work, too. Each work is an interruption to the previous, a reminder that there is no such thing as work-life balance. All jobs and commitments go through mood swings and incoherent chatter. Despite an everyday discipline of work, the resolve to continue doing so is challenged in the artworld where your doing “a lot” is on the same plane as someone else doing “the bare minimum”. Forget about directness; even the artist’s sanity walks daily on the tightrope of remaining motivated and alert in such confusing environs.

I hear you. Now speak softly

Roaring is not for the civilised

The bane of the artist’s practice is an art-world system moored and invested in minting the artist’s pathos. It makes every effort to put you on a pedestal, disassociating you from your peers and asks you to contribute to the “community” in isolation. In the grand mirage of community, how can we ensure that we are in the present, noting the happenings of contemporary society? Every artist believes that there will be world enough and time enough to speak one’s mind.

The artist commits various contributions to the charge of visibility in a world governed by an attention economy. The artist expects universal values, social contracts, and fundamental liberties, assured that the work put out by her will receive feedback, attention, sympathy, understanding, and humanity other than the artist’s own. Take away the prerogatives of this hope, then what one takes away from the scene are these artists who have committed themselves tirelessly. A difference of opinion may not mandate the forking of right and wrong.

Going around an issue exhausts the mind. It creates a gap between what had to be said and what got said. Adding to the most helpful advice in the editorial above, I would like to add my unsolicited two bits: Allow yourself the freedom to speak your mind. It is easier to be the agreeable, amicable, congenial person but fuck that vanilla ice cream attitude.

In his book, These Trees, Those Leaves, This Flower, That Fruit: Poems, Hayan Charara writes:

Young, I thought anger and shame

would in their own time

go away. God,

I was so beautiful then.