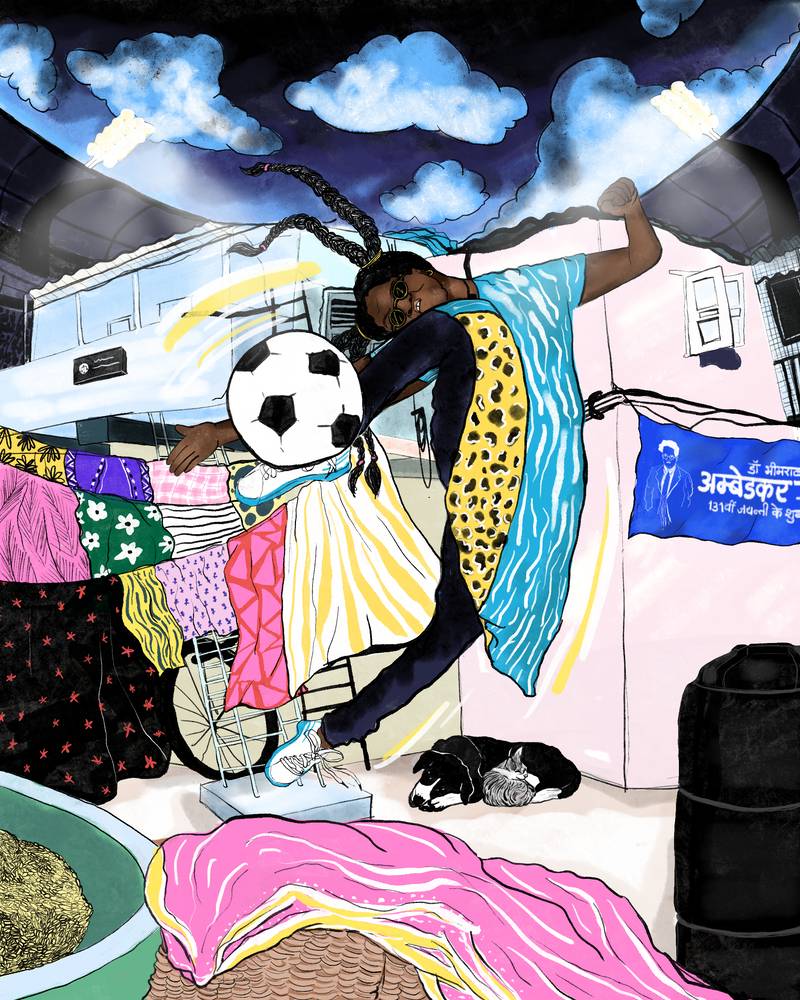

Illustration: Shrujana Niranjani Shridhar

Anurag Minus Verma is a multimedia artist and host of Anurag Minus Verma Podcast. He is also a political columnist who writes regularly for many publications.

In an unequal society, being born privileged is like winning a toss. In India, there is no greater privilege than that of caste. So even as all sportspeople struggle for the nation, whose struggle gets a film?

Olympia, a sports documentary about the 1936 Summer Olympics by Leni Riefenstahl, is unarguably one of the greatest sports films ever made, employing many unique cinematic techniques that were groundbreaking when it was released. Cinema critics, however, are divided about the polemics of the film because behind the film’s brilliance and cinematic craft lies a subtle subtext of Nazi propaganda. Nevertheless, the film features in the Time’s All-Time 100 Movies list.

Whether it is a propaganda film or not, I mention this film because it is one of the earliest films in cinematic history that sensed the power of a sports film to tell a story at the intersection of society, politics, and prowess. Thus, carrying forward the national narrative that suits the establishment, wherein players become representatives of their respective nations.

The idea of the nation is central to the sports film genre, where a rag-tag team of underdogs would represent the nation by fighting the odds or, to quote Nietzsche, performing a triumph of the will and becoming Supermen or Ubermensch. This has been a running theme in most sports films, especially in India, where a rag-tag assemblage of players would beat the white masters and thus take revenge on colonial powers through reparation of the cinematic medium. Such films bind people together and ease the anxiety of divided people in an unequal society. Cinephilia plays inside the darkness of cinema halls where people sit together, their elbows touching each other, and they witness the images of brown men running on the white screen.

I remember watching the Oscar-nominated film Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India (2001, dir. Ashutosh Gowariker) at a single-screen theater in my native small town in India. The crowd in the cinema hall was cheering as if they were on the field where that mythological match was being played. The cinema hall vibrated with slogans of patriotism. At that time, we all believed that the key to our collective happiness lay in defeating Captain Russell (the captain of the British team in the movie). As the lights turned on in the theater, we would all be back to our 4 x 4 rooms, in a trance of being the 12th man that would bring glory to the nation.

In the context of Indian sports films, the recently released film Jhund (2022, dir. Nagraj Manjule) stands out because, rather than taking the audience on an easy trip of nationalism, the film instead asks, “What does a nation mean?” and “Who are the people who are left behind and don’t find space on the bandwagon of national progress?”

Jhund is based on the life of Vijay Barse (played by Amitabh Bachchan in the film), who sets out to form a football team of marginalized slum kids. This is a story about how these kids take refuge in football to transform their current sub-par human condition. The film depicts their struggle to leap across the ‘walls of privilege’ to finally play at the ground where their entry was banned due to the gentrification of sports infrastructure in India, where communities and castes determine access to gymkhanas and clubs where a sport like football can be played. The running theme in this sports film is how we define the concept of ‘nation’ in a country that ‘others’ its own people.

Jhund is a gutsy film to make in an era where the trend seems to return to the cinematic tradition of films like Rocky 4, wherein two superpowers, namely the USSR and the USA, battle it out in a boxing ring. The USA wins the match by punching down the gigantic boxer from the USSR, played by Dolph Lundgren, without even firing a single missile; the Cold War is won in the film. This interplay between a nation’s victory in sports and its supremacy on the global stage is a common theme now in Bollywood. Films like Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (2013, dir. Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra), based on athlete Milkha Singh’s life, show similar themes where Milkha Singh runs for India against a Pakistani runner, all this happening in the post-partition context. The victory on the running track becomes a victory for India that shows not just the athletic prowess but also the civilizational supremacy of the country.

A nation is defined by the differences between people and places. The world is imagined by cinema viewers and filmmakers alike as a melting pot where every community has to mandatorily lose its culture, politics, and history for a utilitarian greater good, defined categorically by putting ‘service before self’ by ‘giving everything’ to make your nation win on the field.

The intersection of nationalism and sports is booming, and the national politics of many powerful countries are moving in the direction of resurrecting the ‘glories of the nationalistic past’. ‘Make America Great Again’, a dream of a resurgent USSR and the idea of ‘Akhand Bharat’ (Undivided India), get traction due to the right’s recent rise to power. Hence, films that affirm the idea of the nation become crucial to the existence of such ambitions.

A nation is defined by the differences between people and places. The world is imagined by cinema viewers and filmmakers alike as a melting pot where every community has to mandatorily lose its culture, politics, and history for a utilitarian greater good, defined categorically by putting ‘service before self’ by ‘giving everything’ to make your nation win on the field. In a scene from Chak De India (2007, dir. Shimit Amin), the Indian National Hockey Team coach, while conducting an introduction session with the team, reprimands them for naming the state they are from and asks them to say they are from India. He emphasizes that he only wants players who will play for India. This innocent-looking moment hides a deeper agenda that aims at not just uniting players with dissimilar identities but rather invisibilising the struggles some of the players may have had to stand on the same field as their privileged teammates. Uniting moments on the field cannot end discrimination, even if prejudices may be suspended in a crucial match moment.

Jhund rejects this sort of utilitarian motive to transcend individual identities in lieu of a national one and instead pegs on the survival of second-class citizens within a society that rejects them as equals but wants them to shoulder the burden of progress whilst being kept away from the fruits of the same progress.

One of the defining moments for sports genre films in India was the box office success of Bhaag Milkha Bhaag. This film started a trend of sports biopics marketed as the real-life struggles of national heroes. It is also interesting that in most Indian sports films, the relatively privileged from unjust Indian society’s standards mimic the underdogs. Even after coming from dominant caste and class backgrounds, the players in these films are often depicted as absolute victims oppressed by circumstance, when in reality, they hold cultural and social sway in the social strata they come from. The protagonist in Gold (2018, dir. Reema Kagti) struggles to assemble a team mostly made up of uppercaste and upperclass gentry as they play hockey to win a medal. Not just the protagonist, but pretty much every lead character here is somewhat socially privileged. Hockey as a game in the colonial era required physical infrastructure, from specialized hockey sticks to protective equipment and a level field. The struggle here is underscored to show these members of society as underdogs when, in reality, they are the next in line by way of hegemony to the British overlords.

In 2016, Dangal (dir. Nitesh Tiwari) was released, which is about the life of a tough father, Mahavir Singh Phogat, and his dream of making his daughters win in the Commonwealth Games. Mahavir Phogat is from the powerful land-owning Jat community of Haryana. One of the struggles shown in the film is how he convinces his daughters to eat non-vegetarian food to meet their protein requirements in a sport like wrestling. Eating meat is taboo and strongly associated with caste purity, where upper caste groups often define their purity vis-a-vis their aversion to consuming meat. A phenomenon seen most recently when government figures banned the sale of meat during Navratri (Hindu festival) in a posh part of Delhi. In the film, the idea is met with disgust from the wrestler’s wife; it is seen as low-activity and unfit for people coming from their strata of society, no matter how crucial it was for the sport.

One doesn’t see sports biopics on Palwankar Baloo, one of the pioneers of underarm bowling in India, P. T. Usha, an ace track and field athlete, Vinod Kambli, an ace cricketer, or Hima Das, another young and prolific athlete – who all happen to come from marginalized caste backgrounds. Even if a story were to make the cut, we would rarely get to see the mention of their caste and would probably get a whitewashed version of their struggle as an effort made purely for the greater good of the nation.

In 2017, a sports biopic was made of Sachin Tendulkar right after he announced his retirement. Meanwhile, pioneering cricketers like Palwankar Baloo fail to find mention in film history due to their caste status and erasure from history.

In a recent release like 83 (2022, dir. Kabir Khan), a team composed of mostly upper-caste players overcomes the challenge of winning a competition traditionally won by those who invented the game. The struggle in these films begins at a point where the struggles of the players in Jhund would begin to end. People who hold absolute sway due to the lottery of being born privileged are shown as underdogs, and their struggle starts when they enter the grounds, as opposed to the players in new-era sports films like Jhund, where the players have to first struggle to cross the gates of gentrification to stand on the same field.

One doesn’t get to see the stories of Dalit sportspersons with active emphasis being made on their marginalized caste, which itself is a bigger hurdle than the sportive challenge for them. One doesn’t see sports biopics on Palwankar Baloo, one of the pioneers of underarm bowling in India, P. T. Usha, an ace track and field athlete, Vinod Kambli, an ace cricketer, or Hima Das, another young and prolific athlete – who all happen to come from marginalized caste backgrounds. Even if a story were to make the cut, we would rarely get to see the mention of their caste and would probably get a whitewashed version of their struggle as an effort made purely for the greater good of the nation.

Films like Jhund and Sarpatta Parambarai (2021, dir. Pa. Ranjith) are a welcome change in recent times where the central characters are from marginalized communities, and special emphasis has been put on the caste identity of the characters. These films are directed by people who have experienced marginalization — Pa. Ranjith and Nagaraj Manjule are both well-known anti-caste voices. These films not only depict caste as a significant impediment to success in a caste-ridden society, but also show the characters asserting their icons. In Jhund, characters celebrate B.R. Ambedkar Jayanti by dancing to the beats of local techno beats infused with colorful imagery. In Sarpatta Parambarai, the main characters are shown holding the portraits of Ambedkar and Buddha as a mark of assertion, making it unique among other kinds of sports films.

Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan in his 1977 lecture, Medium is the message, says, “I would insist on studying the game of cricket as a manifestation of the controlled forms of violence in the community. Baseball or football, any kind of sport, is a dramatisation of typical and acceptable violence in the business community. You can learn a lot about the business community by studying the rules and procedures of cricket, baseball or golf. These games are huge ways of discovering, dramatising what the society you’re in is all about. Without an audience, these games would have no meaning at all. They have to be played in front of the public in order to acquire their meaning. A baseball game without an audience would be a rehearsal only, a practice. The game requires the public, and the public has to resemble a whole cross-section of the community. I’m very interested in games as the dramatising of violent behaviour. Under control.”

One of the reasons why the sports genre is fascinating is that behind the facade of entertainment, it has many layers of subtext and symbolism attached to it. A well-made sports film hides more than what it reveals. This is why looking deeply at this genre can uncover many nuances and tell us a lot about nationhood, communities, politics, and society. With the genre of the sports film itself going into a second innings of sorts, it would be interesting to see what cinematic vocabulary and aesthetics, amid the rising fears of state controls, get produced in the coming times.