Freedom Riders National Monument, Anniston, AL, from left: Setare Arashloo, Zeynab Mohtadi, Kowsar Gowhari

Setare S. Arashloo (b. 1988, Tehran) is a multi-disciplinary artist who is interested in the intersections of art and social, political and environmental movements. She graduated with an MFA in Studio Art from Queens College and an Advanced Certificate in Critical Social Practice from Social Practice Queens (SPQ). She had worked as a museum and art educator in different institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), Queens College, and Empire State College (SUNY). Her collaborative and individual works have been exhibited internationally in the US, Iran, Afghanistan, France, Germany, and Australia.

Freedom Riders Persian podcast is like a travel journal of the narrators, following the story and the route of the Freedom Riders, who were African American and white Civil Rights activists who took bus trips through the American South in 1961 to protest segregated buses and bus terminals. They put to the test a 1960 decision made by the Supreme Court in Boynton v. Virginia that ruled the segregation of interstate transportation facilities, including bus terminals, to be unconstitutional. The 12-episode podcast is like an audio tour of some of the most iconic Civil Rights landmarks and the story of the first groups of the Freedom Riders introduced and discussed in Persian. Currently awaiting the re-publication of the re-edited episodes, I’m reflecting on the experience of making the podcast and what I saw and experienced during the trip with two other friends, Kowsar Gowhari and Zeynab Mohtadi. I’m also thinking about why I participated in this work, what inspired us to do it, and what has changed in me and the world that the episodes are being re-published.

Starting the podcast trip: Arlington, Maryland, April 2021, from left: Setare Arashloo, Zeynab Mohtadi, Kowsar Gowhari

Last April, I was invited by Kowsar for a journey to follow the Freedom Rider’s trail from Washington DC to Jackson, Mississippi, to produce the Freedom Riders Persian podcast. We visited the cities and significant places that the freedom riders passed through, Civil Rights and History museums and Civil Rights landmarks; the encounters inspired conversations among us and unfolded so many unknowns and questions that we shared in the podcast and the Freedom Riders’ story. In the episodes, we introduced iconic Civil Rights activists and had conversations with local activists on race and immigration and voting rights issues. In each episode, we introduced one or two Freedom Riders along with other Iconic Civil Rights activists, trying to highlight influential women such as Diane Nash, Coretta Scott King, Joan Trumpauer Mulholland, and Myrlie Evers-Williams. We also had conversations with local activists discussing race, immigration and voting rights.

I knew Kowsar from the day I set foot in the US, and we became roommates. I flew from Tehran to Dalles Airport, delivered to Maryland’s suburb, and fell into Kowsar’s arm, who sistered me to survive the loss and the confusion of immigration. Kowsar was moving to Baltimore to finish law school, and I had just arrived to go to Art school. Kowsar and I explored the new city together. We built a relationship during our tea table conversations and long hours of driving and discussing our observations of Baltimore, the beginning of the South in the US. We talked about our family background with revolutionary activist parents, my early teens and Kowsar’s youth during the early 2000s, the more open and culturally productive years of Khatami in Tehran and the hope and despair of the 2009 election and uprising in Iran. This friendship and the conversations made the base for our collaboration in making the podcast. Our shared fascination with movements’ history, questions about the US history and what has shaped our experience as Iranian immigrants in the US today dominated our conversations. It led us later to the journey during which we made our podcast.

The primary motivation for making the podcast was the questions and the heated debates about systematic racism in the US and beyond, which were sparked in the US and subsequently in the Persian-speaking communities with the death of George Floyd which was another brutal police killing that fueled the Black Lives Matter protesters and re-energized the movement to demand systematic changes in policing and police funding in the US. At the time of the murder, I was leaving New York City, where I had lived for the past ten years. The COVID-19 pandemic caused job loss and more urgent concern about health care and support systems that I did not reliably have, living the precarious life of an artist/educator in New York. My last weeks in New York were marked by the all-white shirts the BLM protesters were wearing while walking together in the streets of Brooklyn. Walking in protest crowds has never been the same for me after Iran’s 2009 Green Movement silent protests. It’s become an increasingly bodily immersive experience leaving me speechless; it’s as if I see the crowded landscape in silent mode. I left New York with yet another reminder of how limited and colonized my knowledge of US history is. It was with that sense of urgency that Kowsar and I talked, something we shared with many people around the world who were watching these scenes.

The primary motivation for making the podcast was the questions and the heated debates about systematic racism in the US and beyond, which were sparked in the US and subsequently in the Persian-speaking communities with the death of George Floyd which was another brutal police killing that fueled the Black Lives Matter protesters and re-energized the movement to demand systematic changes in policing and police funding in the US.

In 2016, the Trump era’s overall attitude towards immigrants of colour was marked by his Executive Order 13769, AKA the Muslim Travel Ban, placing stringent restrictions on travel to the United States for citizens of Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. This made the link more traceable for many Iranian immigrants between what they were experiencing and the historical, systematic, and colour-coded racism in America. Debates around critical race theory and the rooted racism in the education system in the US were another motivation for me to deepen my knowledge and understanding of racism in the US. The 1619 project by Nikole Hannah-Jones, produced by the New York Times, which I first heard as a podcast in 2019, was an eye-opening, fascinating, and inspiring work in tracing the roots and crystallizing the racist systems of land ownership, education, health care, and policing in the US.

I talked to Kowsar about all of these. We exchanged educational and inspiring resources that we encountered. We loved and followed Throughline by NPR, hosted by Rund Abdelfatah and Ramtin Arablouei. They discussed capitalism and its intersection with racism in a series of episodes. Kowsar and I had talked about going on a Civil Rights tour together when we were roommates. Given the pandemic situation, we decided to design our version of a Civil Rights educational tour offered by the Montgomery County Library, Maryland. Kowsar suggested that we make a podcast with a conversational and in a travel journal format. We wanted to learn more and raise awareness among the Persian Speaking Communities about the history of racism and the Civil Rights movement in the US. I am fascinated with the intersection of art and social and political movements and having worked in archives and museums with movement materials, I was excited to explore more and introduce the paintings, photographs, posters, brochures, and other creative products that were made during the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. The creative strategies of the Freedom Riders and other Civil Rights campaigns and their commitment to non-violent methods are other inspiring aspects of the movement which fascinated us and are discussed in the podcast.

As Kowsar and I reunited in April 2020 in Maryland to plan our journey, the trial of Derek Chauvin, the officer who killed George Floyd, was ending. The jury in state court found Chauvin guilty of all charges. As we hit the road to start our journey, there was a celebration of the court results in the streets of the capital, along with fueled hope and discussions around the systematic changes that these events will (or should) bring about.

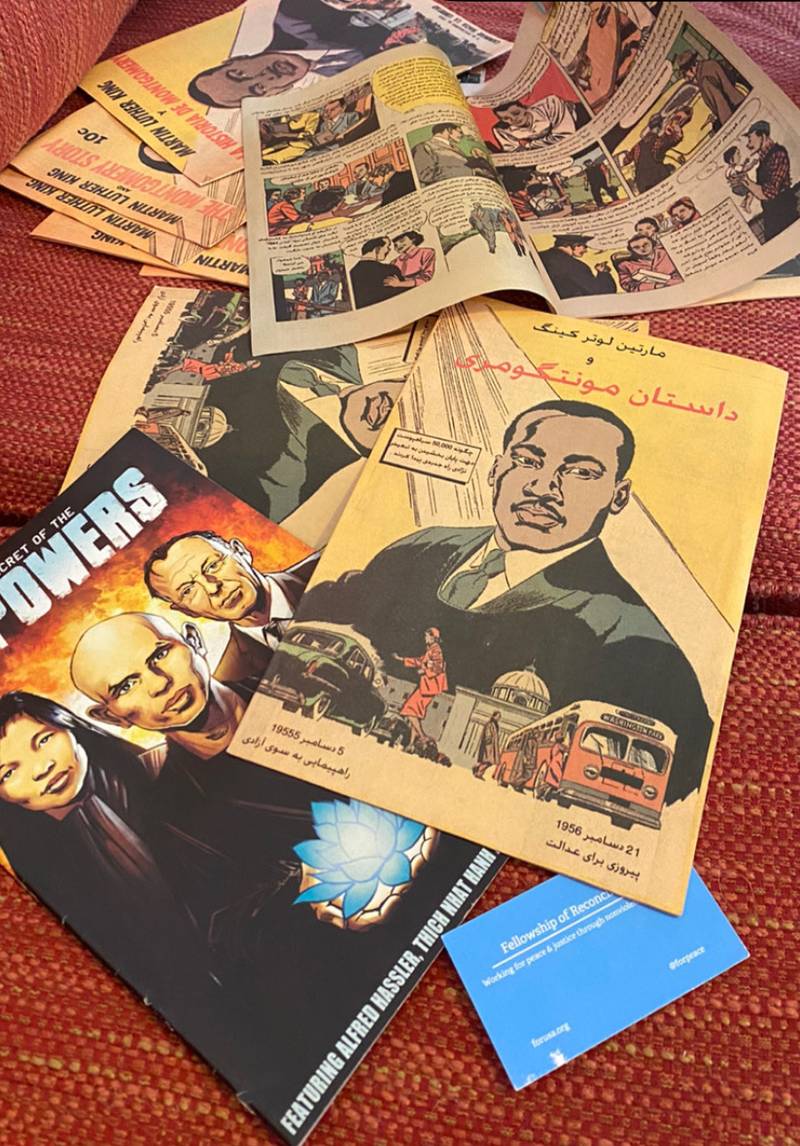

Our first stop was Greensborough, North Carolina, notable for its sit-ins and protests during the early 1960s, which aimed to end segregation in restaurants and lunch counters. Besides visiting the International Civil Rights Center & Museum, we met with and interviewed Ethan Lesley-Flad, one of the directors of the United States Fellowship of Reconciliation Program. He talked about the program’s history and its emphasis on nonviolent alternatives to conflict and the rights of conscience. Our conversation about the possibility of reconciliation in communities with a history of violence and conflict and the idea of historical reconciliation stayed with me the most. Ethan gave us an old classic comic about the Montgomery Bus Boycott, translated into Farsi. He also connected us to Civil Rights activists, current local elected officials, and Civil Rights historians who generously spent time with us and helped us contextualize the history we were exploring while observing the contemporary state of the city and the state that we met them in.

We wanted to learn more and raise awareness among the Persian Speaking Communities about the history of racism and the Civil Rights movement in the US.

The second stop was Atlanta, Georgia. Like Greensborough, Georgia was not on the Freedom Riders’ route but is significant in the Civil Rights movement and is an important election battlefield for Republicans and Democrats. Apart from visiting the National Center for Civil and Human Rights and MLK’s birth and resting place, we met with Mana Kharazi, former Executive Director of IAAB, an Iranian-American youth organization that aims to strengthen the Iranian diaspora community and empower its youth. She talked about the current state of local politics, the mentorship role of the African American activists she worked with, and the importance of connecting Iranian American and African American communities in the US.

At the next two stops, Anniston and Birmingham, Alabama, we focused more on the Freedom Riders and their dramatic and violent encounters in this part of their route. Anniston is where the two buses of the Freedom Riders were destroyed and burned down. One of the most iconic photographs of the Freedom Rides and the Civil Rights movement, with a burning bus in the background and the beaten Freedom Riders in the front, was taken right outside of Anniston by a local journalist, Joe Pastiglione, and published in the next day in the Anniston Star, gaining national and international attention for the Freedom Rides Campaign. The photographer’s negative thought disappeared from the Star records and was not found until 2005, when a local law firm that had defended the attackers of the Freedom Riders found it among the documents that were sorted for destruction. The photographer’s family was ostracized, and he was hung in an effigy at a Kutlas Klan rally. Ultimately, the whole family was made to leave the state. The story of this frame and the photographer is one of those about historical documents and archives that is almost symbolic of the systematic erasure and manipulation of historical documents to control the historical narrative.

Freedom Riders outside of Anniston, Alabama taken by Joe Pastiglione

While in Alabama, we visited Montgomery, where the famous protest of Rosa Parks in giving up her seat on the bus to a white passenger started Montgomery bus boycotts and resulted in the desegregation of city transportation in 1956. Our last stop in this state was Selma, at the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where in 1965, the historic march for black voter registration happened between the city and the state capital, Montgomery. The photographs of this march and the brutal police confrontation with the protesters are iconic photos of the Civil Rights movement. It was quite an experience to walk across the bridge at sundown on the Alabama River. We couldn’t wrap our heads around the bridge’s name today. Edmund Pettus was a Confederate state army officer who was a Ku Klux Klan member after the American Civil War. Being the first and second generation of the 1979 revolution in Iran, Kowsar and I have witnessed many streets and public passage names change in our lives, so it was quite odd to see the old name still on the bridge.

Passing through Meridian, we visited the graves of three activists killed by the KKK during the summer of 1964, during a campaign called Freedom Summer, designed to register black voters in the South and to provide education for the youth. The Stranger at the Gates: A Summer in Mississippi by Tracy Sugerman captures the camping with text and drawings he made during the campaign. The creative documentation with textual and visual notes that captures the moment and the days of the movement makes the book a special work of art, which I found during this journey of the podcast.

We arrived in Jackson at the time of the water crisis in the city and hence the shortage of accommodation. While trying to find accommodation at this time, we got connected to a few people whose encounters added so much to our experience and the podcast. The Freedom Riders were apprehended, arrested, and taken to Parchman Penitentiary. They were initially headed to New Orleans to commemorate the seventh anniversary of the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision, which ruled that segregation in the nation’s public schools was unconstitutional. After violent attacks and other obstacles, the Freedom Riders arrived in Jackson and were arrested at the bus station. After this arrest in May 1961, groups of Freedom Riders started travelling to Jackson by train or bus from other parts of the US. They kept getting arrested and refusing to pay bail. The rides continued over the next several months, and in November, under pressure from the Kennedy administration, the Interstate Commerce Commission issued regulations prohibiting segregation in interstate transit terminals.

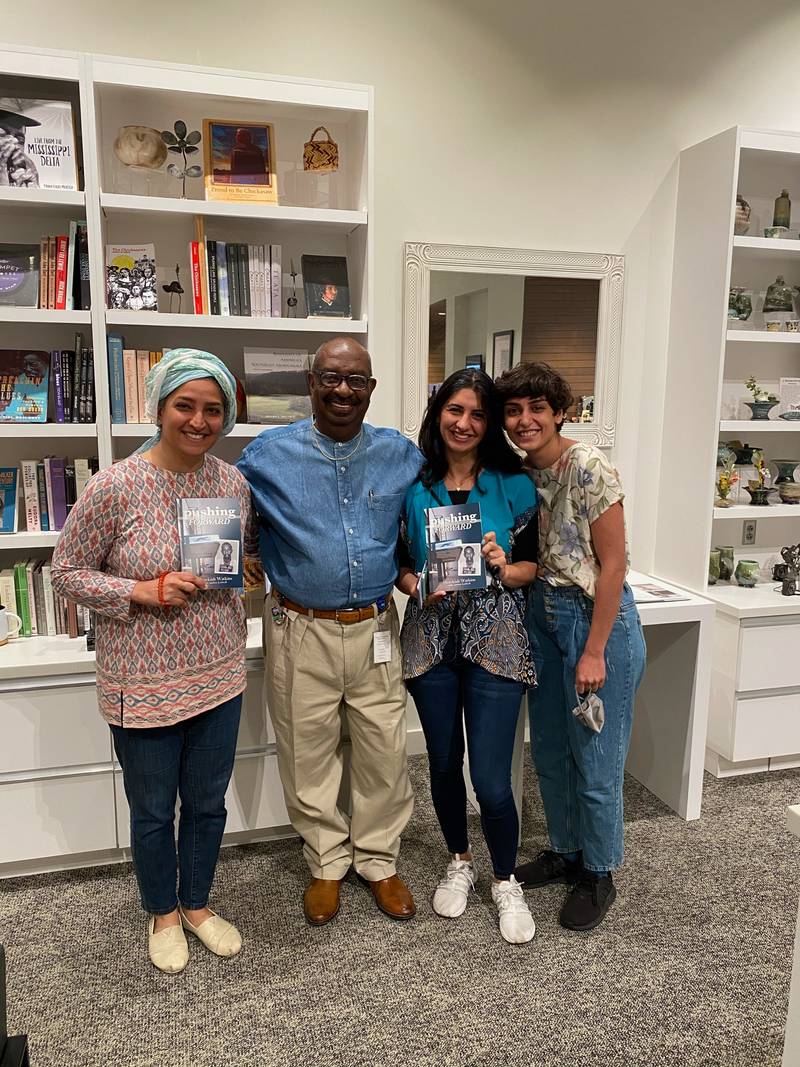

In Jackson, we met the youngest Freedom Riders, Hezekiah Watkins, who, using a lot of humour, told us horrifying stories of his multiple arrests and his time in the movement with his mentor, James Bevel. Hezekiah gave us a tour of the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, where he works, an exceptional and educational experience. We also met with Councilwoman Angelique C. Lee, daughter of Marry Harrison Lee, an Asian Freedom Rider who was arrested with her African American classmates.

We couldn’t wrap our heads around the bridge’s name today. Edmund Pettus was a Confederate state army officer who was a Ku Klux Klan member after the American Civil War. Being the first and second generation of the 1979 revolution in Iran, Kowsar and I have witnessed many streets and public passage names change in our lives, so it was quite odd to see the old name still on the bridge.

Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, Jackson, MS, from left: Kowsar Gowhari, Hezekiah Watkins, Zeynab Mohtadi, Setare Arashloo

The Freedom Riders’ story came to an end in Jackson, but we continued our tour of the Civil Rights landmarks. On our way back to Maryland, we visited Little Rock Central High School, a landmark in the history of school desegregation. We stayed in Memphis, Tennessee, where MLK was assassinated and stopped in Nashville, Tennessee, where the Freedom Rides were organized by a group of students mainly from Fisk University. We met a Civil Rights scholar, Sekou Franklin, who talked to us about how networked local movements gained power and affected change by creating economic, social, and political pressure on the system. Back in Maryland, we published the last episodes, finishing the tour report and discussing the overwhelmingly rich experience it was to see and discuss what we encountered during this journey. The hope and constancy that ran through the Civil Rights movement’s veins were profoundly transforming and humbling to learn about.

One very important takeaway for me from this journey is that there needs to be communication between black Americans and immigrants, whose land and people have been subjugated by colonisation and imperialism. This is a learning process that will benefit us all. Our differences provide us with different perspectives, which help to construct a more comprehensive understanding of our situation when confronting the power structures that oppress us.

Since our trip, we have re-edited the episodes that were only roughly edited at the time of publication. Producing the episodes during the trip was intense. It sometimes felt impossible, but it afforded us more interaction with our audience. We received a lot of support and valuable feedback, which we shared in the next episodes. Boosting the sound quality and re-structuring the episodes as audio tours in a conversational mode, are some of the changes we have made to the podcast. I wonder if the podcast will be heard differently when published in 2022. I have become more cautious about how the content we produce relates to its listeners today. The Freedom Riders Persian Podcast is an educational and hopefully fun Civil Rights brief history in Persian. We share the experience of the journey and discuss sequential, allegorical, or consequential relations of the past that we are exploring to the recent experiences of people of colour and immigrants in the US.

Differences in the social-historical contexts and social grounds, as expected, result in differences in the specifics of each movement. One very important takeaway for me from this journey is that there needs to be communication between black Americans and immigrants, whose land and people have been subjugated by colonisation and imperialism. This is a learning process that will benefit us all. Our differences provide us with different perspectives, which help to construct a more comprehensive understanding of our situation when confronting the power structures that oppress us. The African American experience from within gives us an insight into the workings of power, while immigrants can see its extension on the exterior. The African American experience of victories and failures of various strategies is eye-opening for immigrants, who frequently enter a country and encounter the workings of the power structure in a sudden fashion and may have a delay in forming their consciousness about the landscape they face as international objects of power. In creating unity amongst the oppressed, communication itself can bring about the consciousness that our oppressor is one, using the same tactics against us over and over again, and weaponizing us against the other. To resist these lines that divide us, we need solidarity; not self-centred or transactional solidarity, but solidarity based on an acknowledgement of difference and a conscious effort to learn from them.