Pranita Thorat, a Mumbai-based writer, specializes in the intersection of caste and gender in her research and writing endeavours.

Stories of resistance and various emotions shaped my perceptions and actions in society. Through my lived experiences, I know that representation of the oppressed in any society is a must. Born and raised in a Dalit reality in Maharashtra, I was exposed to Dalit literature as a child – listening to the stories of my ancestors and their struggles against the caste system was also our only source of entertainment. This representation of our lives through the telling of stories has helped me reach where I am today. Without these stories of my ancestors and the teachings of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Mahatma Phule and Savitribai Phule – who fought for Dalit rights, women’s education, and people’s fundamental rights, I would not have been here conducting this interview. The reality that Dalit and Bahujan community in India comes from is the one where they continue to fight for basic needs and resources. After the social and political movements by Jyotiba Phule, Savitribai Phule, and Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, generations of Dalits have been able to safeguard these basic needs and pursue education and livelihood. As a Dalit woman pursuing a master’s degree in Social Work at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (Mumbai), I am living a reality my ancestors would not have imagined – a woman from our family entering a higher education space.

Today most Dalits are first or second-generation learners who are still trying to assert their existence and improve their societal position. In doing so, they prioritise safety and financial security and often enter fields tried and tested by their parents or other Dalit community members – they do not have the privilege of “choosing” versatile careers like art or filmmaking. Moreover, there is limited access and almost no exposure to the process of entering these industries. Even though Art is a storytelling medium that can bring about change, it is arduous and challenging for Dalit Bahujan filmmakers to publish their stories in a gate-kept caste society. Telling a story itself is the Art that propels change. Still, the question remains, how to break through the caste-based gatekeeping and works towards building a Dalit and Bahujan discourse of filmmaking and documenting? To address these questions, I am in conversation with two filmmakers who have successfully documented Dalit reality and presented it to the larger population – Omey Anand, the director of Kadubai and Jyoti Nisha, the director of B. R. Ambedkar Now and Then. In this interview, Omey Anand and Jyoti Nisha talk to us about their process of filmmaking and the way pushed through the hegemonic society and successfully represented the stories of our community.

Omey Anand tuning ektara (one-stringed instrument) while shooting for his documentary Kadubai

“We do not have land. We do not have resources. But we have stories. We have a lot of stories.”

Omey Anand is a filmmaker and an Ambedkarite. He has been representing the Dalit community and asserting his space as a Dalit filmmaker. He is from Karad, a village in the Satara district, Maharashtra. He has released two documentaries, Enlightened (2014) and Kadubai (2019), that depict Dalit reality in Maharashtra.

PRANITA: What are your motivations and process for making documentaries? Where did you start?

OMEY: We didn’t know where to start; that was the issue. A film’s commercial expenses are substantial. If you don’t have any money, you won’t be able to buy a camera. That is the most fundamental requirement. The required quality of sound is unavailable due to the lack of resources our community faces. Sound, music, and the camera are essential components in documentary production. How does one obtain these assets? We’ve just been able to get something as basic as a camera five years ago or so. It’s different for the children of Brahmins or upper caste people. They have had access to these resources since their childhood. When the kid is 5-6 years old, they are given a camera and told - “This is a camera. It makes a film.” We have been kept from all these resources like we did not have technology until now. We’ve just started getting access to it. We could not acquire a camera because we did not have land or land-related resources. So now, when we can somehow struggle and get a camera, in the 21st century, we must use it to acquire land and resources for our people.

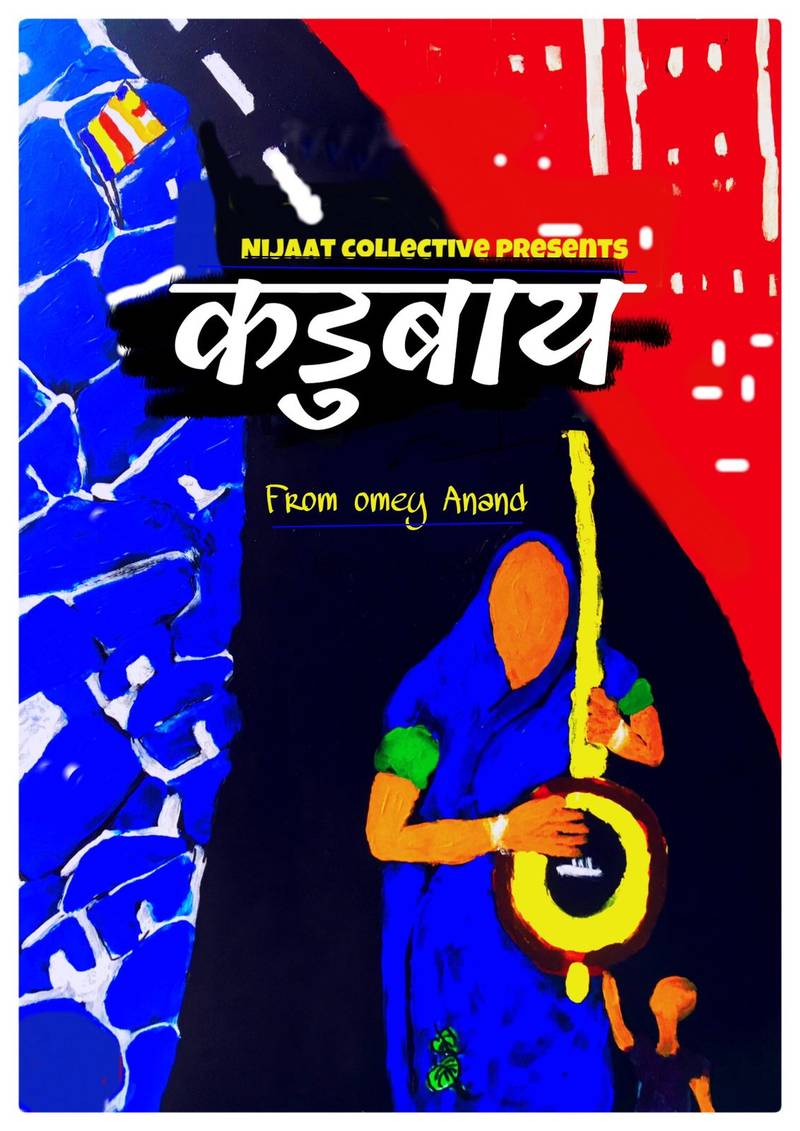

Poster of the documentary, Kadubai

The stories of the struggles to get these resources are the stories I have because I’m a Dalit. What is my background? It is that I’m a Dalit, but I’m not the Dalit who is facing oppression overtly. I’m the Dalit who faces oppression in subtle forms when living in an urban space. The oppression in rural villages is direct, dangerous, and deadlier. It makes you stagnant and does not let you become anything. So telling our stories through films is not a need but a way through which we must assert ourselves. I do not know if society will change. But I know that even if one person starts a discussion, it plays an essential role in our community. There is a need to put forth our views and our experiences firmly. We live in times where even if someone puts a ringtone related to Dr Ambedkar, they are murdered. In such brutal situations, even one person being able to talk about our problems is a lot. Representation is needed and is essential. We do not have any representation in television and cinema. There are no Dalit actors or actresses. And even if there are Dalit characters in cinema, they are shown as unhygienic and of a particular colour complexion. They do not show educated Dalit people or fair-skinned Dalit people. Everyone is beautiful, but why are only we stereotyped and portrayed like this?

Our people are portrayed as dirty in mainstream cinema, and our languages are looked down upon and considered “less than” the pedagogical Brahminical language. But suddenly, I thought of the Dalit Panther movement in Maharashtra in 1972. Their movement was about asserting our language, politics, art, and aesthetics. It was such a strong assertion that the outcome of it is still seen in Maharashtra. The Dalit community in Maharastra is much more assertive and resistant. Your film, Kadubai, significantly impacted me, like the poems of Namdeo Dhasal (Dalit panther). As a Dalit woman, I felt strong when I watched the life story of another Dalit woman who resisted and remained firm.

Kadubai is a wonderful person and singer. Even though she claimed to be unaware of any such effect, it was clear that her singing made a difference for herself and others. When we worked with her, she lived in an encroachment area in Aurangabad. The government eventually claimed that land after a few years. When making the film, I thought that if the camera gets to Kadubai, it should also show the other 300-350 persons who live there. In the two years we spent with Kadubai, we lived in the same neighbourhood as activists. Our main political goal is the annihilation of caste. An effective representation of caste realities can achieve a part of this goal. If you see, our realities are barely represented in the art space, and if we ever find our lives in the media – these realities are misrepresented. The gaze is all wrong. So, when making Kadubai, it was imperative to use the camera and show Kadubai’s life, her strengths, and how she resisted society. The phenomena should be converted into noumena, primarily through the camera. Since we were determined to make this short film, we secured a camera and other necessary equipment and moved on to the question of Why we wanted to make ‘Kadubai’.

Our main political goal is the annihilation of caste. An effective representation of caste realities can achieve a part of this goal. If you see, our realities are barely represented in the art space, and if we ever find our lives in the media – these realities are misrepresented. The gaze is all wrong. So, when making Kadubai, it was imperative to use the camera and show Kadubai’s life, her strengths, and how she resisted society.

Still from the documentary, Kadubai, seen here are Kadubai with her daughter

I think the representation of the oppressed is critical in any society; it gives others a space to relate to someone, find similarities and thus feel they belong. Audiences from varied social and societal locations have different expectations from an artist. Do you sometimes create art that, even though it successfully appeals to the audience, maybe compromises your ideas of the film?

There was a time when I thought that filmmaking was about attending to how an audience sees it, meaning how people perceive it like an object, or maybe they relate to a character from the film and not the whole film. An audience can also be prejudiced or ignorant, and so their perceptions have limited resources of references. For example, the audience may readily accept that a woman is dark-skinned and poorly groomed simply because she is Dalit or Adivasi. These concepts of beauty standards are casteist and bogus. My caste is beautiful because it has gone through so much. We have stood firm against oppression all these years, and the stories we tell are beautiful, from stories of rebellion, such as the story of Urmila Pawar in her book “Weave Of My Life” (1988) to songs by Vamandada Kardak. These stories have inspired us to keep moving ahead despite all odds set against us. I and some Dalit individuals interested in filmmaking formed a group and made films, although none were released. Only one short film I directed, Enlightened, was released in 2014. So, when we completed making Kadubai, we had no idea where and how to release it and who would assist us in the promotions. Initially, we organised paid screenings to recover costs. With time, we screened our short film at festivals and venues such as Dalit Film Festival in New York, Max Muller Goethe Institute in Germany, SRFTI in Kolkata, etc.

Now let’s consider land as a metaphor, a metaphor for resources. There is no land, no water, and other primary resources. So the stories that we present have also grown from the same landless reality. When you ask someone for their story, they say, “I don’t have land, give me land, I don’t have a house, give me a house, I don’t have water, give me water.” The story talks about all this.

It’s an outstanding achievement that you could screen the cinema at different places, and the story reached a wide audience.

Does the necessity and desire to depict our community’s story feel pressurising? Do you believe the urgent need to present our people’s reality is a no-choice condition in which we live and work?

The first thing is that we don’t have land. We don’t have land because we are Dalits. We have struggled since before independence, which has been ongoing till today. Even before independence, our generations have not been able to progress because we didn’t get essential resources. We know this because we are Dalit; we are landless.

Now let’s consider land as a metaphor, a metaphor for resources. There is no land, no water, and other primary resources. So the stories that we present have also grown from the same landless reality. When you ask someone for their story, they say, “I don’t have land, give me land, I don’t have a house, give me a house, I don’t have water, give me water.” The story talks about all this. Their perspectives keep changing, but these stories remain.

So, even if we make a film solely for amusement, it would incorporate our realities and become a film about resistance and thus political.

My film should show the people around me, the colony I come from, the smell of the naala, and the chickens that peck at different things. This imagery of the colony I come from, our reality, is missing in the films made by oppressor caste filmmakers. So the lens with which the audience watches a film is casteist, a theory I also connect to my research for my master’s thesis, Untouched Camera. It explores the phenomenon that the camera is untouched; we, the Dalits, are not allowed to touch the camera. Another aspect of the research was that if the lens you see is through an oppressive casteist lens, then the film will also be casteist. I don’t want to make a casteist film. I want to make beautiful films and tell beautiful stories of our Dalit reality.

Last year, I saw Geeli Pucchi, where she was the Assistant Director, and I have been curious to know more about her practice. I have followed Jyoti Nisha on social media for the past few years and have become familiar with her practice through her writing and interviews. From my point of view, it is difficult to find a Bahujan woman in the casteist and patriarchal world, so to be able to see Jyoti Nisha’s work is motivating. I wanted to know more about her journey, her ideas, what inspires her and how she brings together ideologies of Dr. Ambedkar and feminism within filmmaking practices.

Jyoti Nisha

“I know how structural hierarchies can be annihilated. It needs collective work.”

Jyoti Nisha is a Mumbai-based academician, writer, screenwriter and filmmaker with a focus on cinema, gaze, caste, gender and media, and has over ten years of experience in print, radio and T.V. She has directed, produced and crowdfunded her upcoming documentary film, B. R. Ambedkar: Now and Then in collaboration with Pa Ranjith’s Neelam Productions.

I have seen glimpses of B. R. Ambedkar: Now and Then, and it made me think about how you must have travelled to those places, again and again, to bring forward the essence of the anti-caste movement in today’s time. The scenes of women walking with panchasheel flag in their hands, students protesting against discrimination in higher educational institutes, and various other symbols you have captured reflect upon the strength that we as a community gained over the years because of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar. There is also a depiction of Buddhism and the liberation that the Dalits in India could have, also experience liberty of thought and practice equality by standing against injustice. One has to be in the field for a long time to see the minute details and depict them in a film. I’m curious to know how long you have been working on this film and what was the process you went through.

JYOTI NISHA: I’ve been working on the film for five years. The idea of ‘now and then’ was already on paper when I started.

I shifted back home to Lucknow in 2014 because my mother was not keeping well. During this time, I had many conversations at home. My father, Late. Net Ram Singh was in the anti-caste movement, so a lot was happening in the background growing up. I participated in those conversations, but as a kid and even as an adult, I didn’t delve into it deeply. Unbelievably, conversations about the annihilation of caste are not part of popular perspective or knowledge. It almost seems like a conspiracy as to why and how come. My father passed away when I was 16, so I cannot talk to him about what I’m doing now in my life; I cannot have those conversations with the person who was part of the movement in the country. But my brother and I talk. I quickly realised that these perspectives are not common knowledge, so there must be a reason. At home, we had the knowledge of marginalised assertion and Babasaheb’s movement. I, too, was trying to explore why and how you can be less deserving than everybody else in some way. And to address these structural hierarchies the film B. R. Ambedkar: Now and Then came to form.

In 2015, my mother, Seema Singh, passed away. Naturally, it was a lot to process, mentally and emotionally. Then, in 2016, Rohit Vemula was institutionally murdered, and the loss felt personal and intense. So I started questioning the way we see things and this whole popular perspective, then gaze. At the same time, so much was happening in the country: Rohit Vemula’s institutional murder gave rise to an entire movement around anti-caste politics, a lot of films and conversations around Babasaheb were also being made, Jignesh Mevani’s Asmita Yatra took place, Chandrashekhar gained visible popularity and their thoughts resonated with mine. I was like, kuch toh bhayankar ho raha hai (something huge is happening). The idea of ‘now and then’ started making sense.

I learned about him and other revolutionaries and their thoughts during this film. At the same time, a strong Ambedkarite assertion was developing in the country. It all started making sense. My brother and I were talking about Mahad Satyagraha through the newspapers of Babasaheb. I was like wow, ye kiya, woh kiya, separate electorate maanga (did this, did that, asked for a separate electorate), this is amazing, kisine kuchh banaya kyun nahi hai? (why has no one made anything on this?). Then I felt, why don’t I tell this story? It has been exhausting. I was also grieving and mourning my mother’s loss, so that’s also why I kept at it because there was something very personally driving me as well.

I think the film’s idea resonates with many. Earlier I used to think that I was the only one speaking. Now I feel like what I’m saying makes sense to people, we have shared histories. I give credit to my family and the legacy of the anti-caste movement in the family and in the country. And if I don’t do anything about this legacy, it’s a loss.

It’s five years of work with a small budget and team: one camera person, one sound recordist, then small budget, no high-end equipment. Editing a Documentary is exhausting; seeing a hundred or two hundred hours of material, figuring out a 60-90 minute film, oh my God, tum marr jaate ho (you die). I had wrapped the film last January, but when I showed it to distributors, they were like, “this is very political”, “tough to sell”, or they asked for changes to make it “better” or “sellable”. There is added pressure, you don’t want to piss people off.

I went to eight states, crowd-funded for the post-production of the film. Now I am reworking some parts of the film. People have been waiting. I have been waiting. We had two years of the pandemic. I don’t know what people are expecting from me. It’s crazy. Making the film is one whole game; selling and distributing is another. I understand there is an audience for it. Some people who started following me and my work through social media have become friends and are supportive and appreciative of my work. I think the film’s idea resonates with many. Earlier I used to think that I was the only one speaking. Now I feel like what I’m saying makes sense to people, we have shared histories. I give credit to my family and the legacy of the anti-caste movement in the family and in the country. And if I don’t do anything about this legacy, it’s a loss.

But the film-making process starts with not knowing people, not having “connections” per se. I’m a writer, not a filmmaker, so I did everything on gut instincts, making mistakes and sometimes choosing the wrong people to work with. I’m still learning things. Just being attracted to film-making is not enough; it is hard work. When I worked with Neeraj Ghaywan on Geeli Pucchi, my first commercial work, we were shooting for sixteen hours straight, which are standard work schedules. Standing and running around on these sets with ten-minute breaks is burning blood and sweat. I didn’t realise this five years ago when I started B. R. Ambedkar: Now and Then. It’s exhausting. I’m still tired as I have finished the film.

I believe we grow as a community and as a movement by repeatedly telling our stories and having difficult conversations. What are your thoughts about the work you do?

I appreciate knowledge and perspectives that are different from mine. I theorise the Bahujan spectatorship because it gives me an empowered perspective toward the marginalised people of this country. If legacies and stories are not passed on, new generations will come around and say hey, humein pata hi nahi tha (we didn’t even know). To that, I want to say, here, I’ve written this, I’ve made this. Use this knowledge. It is a point of contention, intervention, a conscious effort, like a conversation.

I know how structural hierarchies can be annihilated. It needs collective work. I don’t care where you come from, that’s not in your control, but I do care about what ethics you bring to the table and how open you are to the conversation. If you want me to listen, I expect you to listen too. It has little to do with age and any other labels. It’s about ethics and imagination to produce new, original, and genuine work because that kind of work liberates you. It heals you and transforms you. You have to make people experience something that they have not experienced.

There is some kind of commitment which is there, but nobody has asked me for this commitment. I have only committed to myself, you know. Over time, I realised that some people are connected and committed. There are also people who are talking about identity and the movement. Whereas there are people who are doing it for the sake of the revolution that we want to have. I’m an artist and a romantic, so I don’t think I will not be honest about pursuing this work.

See, artists are very feeling based. I’m driven by intuition which comes with age, experience and working with yourself. So even though you don’t set out with an agenda, there comes a point in your life where you ask, what are you doing actually? Why are you telling stories? What is the significance of the story itself? I am an analytical person, mujhe dikhayi bohot jyada deta hai (I can see a lot of things), and it can get overwhelming. I’ve always felt that you have to lead by example if you want to bring people together and work with you… doesn’t mean that it will necessarily work out.

On a philosophical and personal level, I don’t care what the world is doing. I want to see what I can do. I’m extremely critical, ask questions, and dig deep; I need nuance. We are layered individuals full of possibilities. So, whatever I do, I do with wholesome attention, hoping that the wholesomeness is communicated. I’m not the only brilliant one, and I have high regard for people from our community and even outside our community, those thinkers who have produced knowledge.

And if you see, systematic discrimination of caste which is socially and religiously sanctioned becomes a pressure for sure, not settling down, not getting married, just film ka hi kaam chal raha hai (only the work of films is going on), trying to create this knowledge base, which is so exhausting when you’re doing it all by yourself. There is some kind of commitment which is there, but nobody has asked me for this commitment. I have only committed to myself, you know. Over time, I realised that some people are connected and committed. There are also people who are talking about identity and the movement. Whereas there are people who are doing it for the sake of the revolution that we want to have. I’m an artist and a romantic, so I don’t think I will not be honest about pursuing this work. So yeah, that’s how I am as a person, so yeah, that’s why I use that identity. There is obvious pressure, but I think everybody somehow deals with it. So it’s not a big deal. But also, it’s the way you look at it, the way you deal with life, so I tend to deal with life that way. I’m not a person who will stay defeated or depressed for a long time. I will push myself to get out of it, no matter what. So yeah, that’s it, that is what I think baaki (apart from that) I’m just chilling. I like to chill, and I like work. If I don’t chill, I can’t work.

B. R. Ambedkar: Now and Then, directed by Jyoti Nisha will be releasing soon.