Camille Auer is a trans-disciplinary artist and writer. Her art practice has always been theory driven, but instead of illustrating existing theories, she uses forms ranging from sound, moving image, performance and text-based installations to contribute to theoretical discourse as modes of thinking in their own right. Her rich body of work is diverse in form and content, but a common theme is the othering of trans and nonhuman bodies, such as herself or queer birds. Her work has been shown and published in The Finnish Museum of Photography (Helsinki), Wäinö Aaltonen Museum (Turku) and Atlas Arts (Skye, Scotland) among others. Her work is currently supported by the Finnish Cultural Foundation.

Content notes: Animal cruelty, the threat of violence, discussion of death and suicide.

I almost got thrown in the river after seeing Reija Meriläinen’s exhibition Snugglesafe, which was on view in Turku’s Titanik gallery July 7–31, 2022. The adrenaline rush poured out of me as the first draft of the following text.

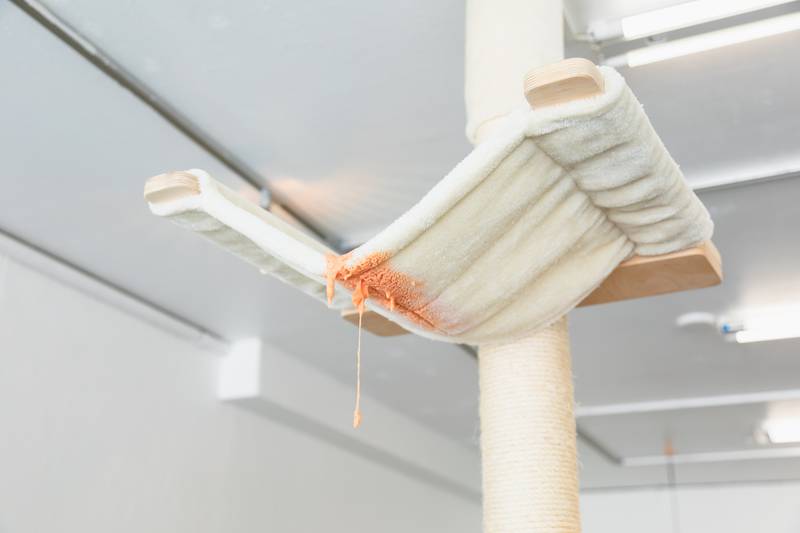

Snugglesafe is built around the artist’s experience fostering homeless cats and kittens. The exhibition opens with a series of sculptural elements installed in the first of Titanik’s two exhibition rooms. The dominant colour is a peachy orange, and the materials range from glossy and smooth silicone to fluffy fake fur. Some objects are similar to everyday things related to keeping cats, a climbing tree, climbable shelves on the wall, and cat beds. This everyday impression gets nudged toward the uncanny by some extra elements. From a shelf of the climbing tree, some sort of goo is dripping onto the floor, like a cat had lost the surface tension holding it together and became shapeless matter.

Two cute plushie kittens inhabit this imaginary cat house. One has instructions to handle it roughly, and when you do, it starts twitching in spasms, powered by an electric motor. Some of the sculptural elements appear to be imaginary renditions of the internal parts of cats. An object resembling a spine is built around a steel pipe with a roll on its upper end. The vertebrae have a glossy surface. The roll is covered by tiny spikes, like the surface of a cat’s tongue, suggesting a licking machine. Another structure resembles a pelvic bone. A large, round, silicone form is hanging from the ceiling by a harness – a teat protrudes from it and slowly drips a liquid. I reckon it’s in the scale for a human a mother’s teat would be for a kitten.

The exhibition’s central piece is a video playing in Titanik’s second exhibition room. The walls are painted with a thematic peachy colour, creating a warm, nest-like atmosphere. Two armchairs are covered with fake fur, and their legs end in cat paws. It feels like a cat held you, and the proportions between a cat and a human have switched.

In the video, Meriläinen does the chores necessary to keep kittens alive when their mother has abandoned them. They are wrapped in a towel for feeding; sometimes, this must be forced. Their bellies are rubbed to make them pee and poo. Milk temperature is checked by dropping it on the wrist. Meriläinen is dressed in a suit with some of the intestines, made from textiles, hanging on the outside. I think it might be the same suit they made for Emmi Venna’s performance Fabulous Muscles. The internal and external switch places a repeated motion in the exhibition.

The routines intensify when a kitten is sick. The artist is talking to the kitten, telling them their name, Natie, and how the name is shared by a cute fantasy character the kitten, unfortunately, can’t see because they don’t have eyes yet. The spasms of a being with no eyes and no experience of more than a couple of days of struggling existence make me think there must be nothing but pain. There is nothing to compare the pain to, which makes it immanent and omnipresent. This is footage of a human doing everything possible to keep a kitten alive. Straight cut to the kitten being dead. Straight cut to the kitten without a head. The mother bit it off; I remember seeing this on Meriläinen’s Instagram at the time of the happening. The tension Meriläinen has pulled between the strange and the normal, the internal and the external, life and death, feels intense, for some viewers, perhaps too intense.

Death is a normal part of life, yet it will always remain unknown to us. None of us gave our consent to be born, but most of us just roll with it. Meriläinen has taken their art practice to the edge of death before, in their exhibition Faint in the late Å gallery in Turku. The show revolved around Chester Bennington, the singer of Linkin Park, who died by suicide. A screen was playing a youtube playlist titled Linkin Park, but everytime Chester screams, I kill myself with 300 videos of Linkin Park live concerts, music videos, and fan-made videos. Blankets and pillows installed in the space were painstakingly hand-embroidered with depressive Linkin Park lyrics and other texts. A zine with a printed-out chat conversation, presumably between the artist and a friend, revealed the artist was checking in at a hospital, feeling hopeless and unsure if they could make the exhibition, which contrasted with the high level of effort and expertise put into the textile works. This relates to Snugglesafe in the way the objects are made with technical finesse a few artists can reach, which creates an elevated atmosphere and prepares the viewer by invoking their imagination to deliver the core gut punch of the exhibition – the raw presence of death. The videos in Faint and Snugglesafe show the (alive) viewer, someone who is dead at the time of viewing. Fantasy, and perhaps empathy to that which has just passed, is the closest we can get to death and remain to tell about it. In less capable hands, both exhibitions might have come across as edgy. Still, Meriläinen handles death with the care that encourages an attunement towards the beauty of the temporality of life.

There is nothing to compare the pain to, which makes it immanent and omnipresent. This is footage of a human doing everything possible to keep a kitten alive. Straight cut to the kitten being dead. Straight cut to the kitten without a head. The mother bit it off; I remember seeing this on Meriläinen’s Instagram at the time of the happening. The tension Meriläinen has pulled between the strange and the normal, the internal and the external, life and death, feels intense, for some viewers, perhaps too intense.

The death of a kitten in a contemporary video piece in Finland, of course, compares to the infamous Sex and Death or its later version, My Way, Work in Progress from 1988 by Teemu Mäki, better known as the “cat killing video”, an artwork everyone knows of, but few have seen. In Mäki’s work, a cat adopted from an animal shelter is killed by the artist and then ejaculated on. The act is contrasted with the material structural violence all people who benefit from global capitalism are complicit. In Meriläinen’s work, all efforts are made to keep the kitten alive. The choice to film the last moments of its life could be questioned since making artwork as a professional artist always has the aspect of furthering the artist’s career. The prospect of bringing light to the suffering of homeless cat populations outweighs this worry, at least for me. Cats in Finnish art discourse also bring to mind the fuss that sparked when former minister of culture Pia Viitanen said in 2014 that she would like to have a cat painting when asked in an interview what kind of artwork she would choose for her office wall. This was considered a sign of ignorance towards the art world at the time.

The proximity to pain and death left me fearless when I walked from Titanik to the library on the other side of the river. I saw a tattooed guy looking like a bodybuilder, repeatedly pulling at his dog’s leash on a strangling collar. I yelled in Finnish, stop strangling your dog. He didn’t react. I repeated, hei dorka, älä vittu kurista sun koiraa. He didn’t respond. I continued walking to the library. After returning my book, I went to the other side of the library and saw the guy again, waiting for someone, still strangling the dog. I walked past but couldn’t resist trying to stop him from strangling his dog. This time, he replied in English, what’s up, bro? Ok, so he misgendered me, which left me with no womanhood to retreat to but also with more adrenaline. I saw you strangling your dog from there, so don’t do that. Mind your own fucking business, he retorted. I said first, learn a thing or two about dogs before you get one (that being, don’t inflict pain on your dog on purpose). He said the fuck you just said. I repeated myself. He said I’ll put you in the river, that’s what. Once more, I said,* learn how to keep dogs before you get one,* and gave him the finger. His wife (presumably) came from a cafe with a baby carriage. The guy tried to give the dog’s leash to the woman so he could put me in the river, but the woman said, Danny, no, don’t. She didn’t take the leash, so the guy started running with the dog, so I started running. Run, bro, you better run! He said. I just ran and glanced at the dog to see if I needed to worry about them attacking me because running faster than a dog is impossible. The dog looked confused and not aggressive. At one point, the guy stopped running, and I had some distance, so I also started walking. Then he started running again, and so did I. I ran to the Book Cafe because that felt like a space where I would get support if he followed me. I went straight to the bathroom and locked the door. I haven’t done much sport lately, but I thanked my body for being faster than his. I coughed for an hour from the effort. A friend was in the cafe and gave me a lift, so I didn’t have to risk running into him again. I wish I could have told the guy that I’m trans, so if you put me in the river, that would be a hate crime.

I don’t know if I would have yelled at him if I hadn’t just been in the exhibition, so that’s how this wraps up. I could have tried talking to him in a way that didn’t immediately escalate the situation. He also would have taken it differently if he had taken me for a cis woman. I also hate when people tell me what to do with my dog, but guys like him usually have all the wrong ideas of how to be with a dog.