Illustration: Tara Anand

சிந்துஜன் வரதராஜா (Sinthujan Varatharajah) is an independent researcher and essayist based in Berlin. The focus of their work is statelessness, mobility and geographies of power with a special focus on infrastructure, logistics and architecture. Their first book “an alle orte, die hinter uns liegen” (“to all the places we have left behind”) was published in September 2022 in Germany by Hanser Verlag.

Date: December 31, 1994. Location: a crammed living room in a council flat.

We were busy watching a live broadcast on a Sony KV-C27 TA television. The device was prominently placed at the centre of the room, rendering it difficult for anyone entering the room to overlook and overstep it. And yet my eyes were struggling to hold their focus on the modern device’s flickering 29-inch Trinitron screen. They instead kept on moving towards the dated gold-framed wall clock hiding above the sliding kitchen door, quietly announcing the time of the day to its occasional viewers. I was caught by the clock hand’s rhythmic movements: one-directional and restless. The machine chased one Arabic numeral after the other, approaching a digit while leaving a different one, always seemingly unsatisfied with its own progress in distances, digits, and time. After a few seconds of watching this never ending chase, my focus returned to the bulky TV put on top of a wooden stand covered with fine white ornament tablecloth. There too was a clock. It was stuck to the right corner of the screen. Not central enough to catch viewers’ full attention but equally not marginal enough to be completely overlooked by them. Albeit similar in design, the technical components of the clock on the screen and the clock hung against our living room wall were different. One of them was analogue, the other digital. The latter also showed a slight delay in time. When viewed from the right (or wrong) angle, the digital clock seemed as if it was chasing the analog one. But the chase didn’t come to an end. It couldn’t really. Both were evenly running away from one another. There was no opportunity for their hands to meet each other. My focal point was suddenly disturbed when the broadcast was switched to a different channel by my father. The clock had disappeared, only to reappear a few seconds later when the television switched back to the previous channel. In the meanwhile the displayed time had changed. The broadcast’s location had also shifted. We were suddenly no longer gazing into a broadcast studio in Mainz, Germany, but towards Te Whanganui-a-Tara, Aeotohara, more precisely at the city’s harbourfront. The cameras were zooming on the dark sky above this waterfront. It was on fire. But it wasn’t just Aeotohara that was burning. The fire was moving. It was spreading fast.

An hour later, it had travelled across the ocean and reached Sydney’s Harbor Bridge. From there, it swam to reach Tokyo’s Sensoji Temple, then to Hong Kong’s Kowloon Bay, Singapore’s Marina Bay, and Moscow’s Red Square, until it had reached, with a slight delay in time, the sky above Brandenburg Gate. By the time it had reached Berlin, ten hours had already passed. The fire had already caught half of the world and turned its ceiling into a multicoloured spectacle. As the skies above these human settlements were burning, they were burying everything underneath them in smoke screens. The width of this fire seemed endless, expanding in what seemed like all directions. But that wasn’t true. The fire was moving in a single, or actually two particular directions: westbound and northbound. It was steadily moving towards us. Likeso, the sky above our very heads had changed in colours too. It shone in garish tones, arguably far less opulent than the skies above the many capital cities we had watched on the Sony KV-C27 TA just minutes before.

While the machine in our living room showcased capital skies through its screen, it didn’t mirror the countryside sky above us. There were no cameras documenting the scars that were showing on its surface. Indeed, there were no technical aids to allow for the image to travel via cables, broadcasting vehicles, satellites, and a few milliseconds delay back into our living room. But by that time the television had no longer been the centre of our attention to begin with. Our focus had shifted when the fire had reached Moscow’s Red Square. Ever since we had devoted ourselves to another, more immediate screen: the window. The Sony television prominently became no more than a background prop that no longer threw its light against our eyes, but the back of our bodies. While observing the sky above us, our new found relationship to the window was repeatedly interrupted by a noise different to the one of the television: the ceaseless ringing of an analog phone from the hallway. To relieve all window observers from the device’s penetrating noise, one of us had to step away from the window to pick up these calls. An enthusiastic ‘Happy New Years’ was to be heard from the other side of the cable. It was met with a similarly cheerful ‘Thank you’ and ‘Happy New Year’, all articulated in English, before the phone was handed over to the next well-wisher, who one by one had to move from the window to the hallway to pass their greetings. This ceremony, both formal and familiar, was repeated a number of times, up until 3 am local time, when the fire above us had long been extinguished by the dark of the night.

This procession followed a returning order: once New Year’s wishes were exchanged in English, all speakers immediately switched to Tamil, the primary and only language of communication between all callers – almost as if the New Year we had watched through two different screens, the New Year we had congratulated each other for and celebrated from a distance, that is the window and the television, fell outside of the language of our very homes. The telephone rings were however not just interruptions or additions to the sonic interplay between television, fireworks and onlookers. Their entry wasn’t just an inconvenience to us, forcing us from the windows back into the interior of the council flat from where we had no opportunity to see the ongoing lighting of the skies. They were also desperate attempts of different callers to bridge over barriers manufactured by that same modernity that had gifted us these very technologies that began to shape and drive our everyday lives.

When connected, our voices traversed over such lengths that neither the capacity of our lungs nor the echo of our voices could independently carry our sentiments towards their recipients. We instead relied upon technical aids, submarine cables, and other modern devices that supported our voices, transmitting them from one side of the world to the other… The price of each word was their respective length and weight. From our Happy New Years, Thank Yous to all following words exchanged in a language different to English, each of them came with a specific price tag. This wasn’t to be felt at that very moment but much later, when the monthly telephone bill was to fly in at the end of each calendar month. That however was an afterthought on the night in question. Such thoughts were reserved for the day after. Or rather the year after.

Telephone cables spanning oceans and continents spatially tied us together. They carried the potential to further merge our understandings and feelings of time, shifting our temporal reality, creating a shared present that could stretch across different geographies and with it also vastly different time zones. These copper wires hidden within PVC jackets allowed us to be present in places and during times we otherwise remained absent, or no more than afterthought. By picking up the phone at the end of our day, we were able to be present at someone else’s start of the evening or morning. We were able to disrupt each other’s otherwise separated timelines, intruding and collapsing individual and collective senses of and for time and space.

Minutes before midnight of December 31, we hadn’t just reached the end of the day line, but also the edge of the year line. While some of the many callers talked to us from within the same year, others were already calling from the year we were anticipating from the window. They were welcoming us into the year they had already successfully reached. They called us from the other side of the year line - from our future. Minutes after we had passed this detrimental line, others would call from the day and year we had just departed. They were congratulating us on our successful trespassing. At this point, we weren’t talking to our future or our present anymore, but to our past. Within a cycle of mere twenty-four hours, the temporal distances dividing and defining our relationships became difficult to ignore. We had reached the edge of time.

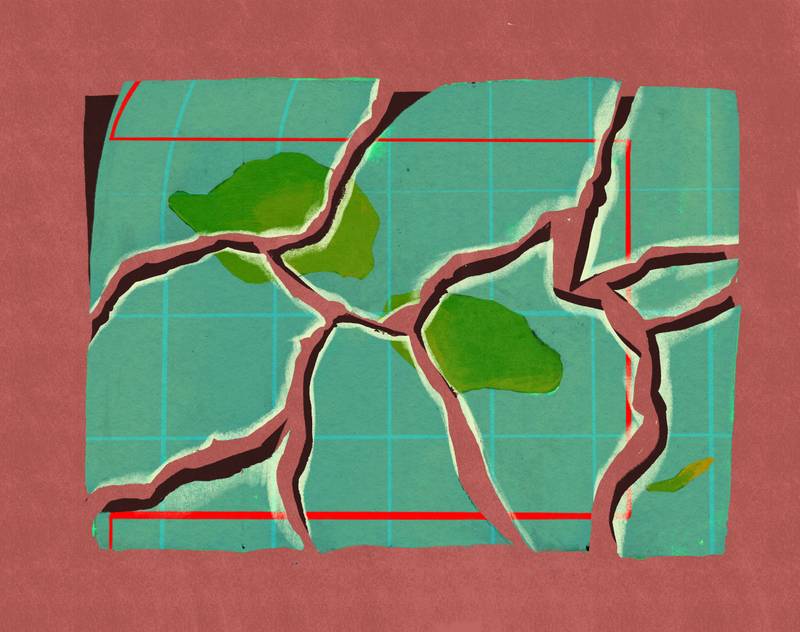

The edge of time is a place, more specifically a line, dividing today from tomorrow, yesterday from today. From where we were in 1994, it was thousands of kilometers away, so far away that it remained an abstract that was only felt during specific times of the year. It was mostly out of our mind precisely because it was mostly out of our sight. In Samoa, an archipelago situated closeby to the said line, this border was however not abstract. It wasn’t something that could be as easily ignored throughout the remaining year. The line was too close to overlook. By way of geographic proximity, the island chain was more likely touched and disturbed by it. In 2011 the government of the territory thus took matters into their own hands. It decided to change its own future by changing its own place in time. To achieve this modification, Samoa decided to get rid of December 31 2011 in order to be able to slip through the thread of time. While the world had remained in its configurations of time, the island had, with a blink of an eye, altered its own configuration of time. By disappearing December 31 2011, by erasing twenty-four hours, Samoa catapulted itself twenty-four hours ahead into the future.

Samoa jumped from our Central European yesterday to our Central European tomorrow. In doing so, it skipped GMT negative twelve, eleven, ten, nine, eight, seven, six, five, four, three, two, one, zero, one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven, twelve, thirteen and all other intermediate zones, to reach a time different to the time it was destined to live under for decades. This time loop allowed for the inhabitants of the island to skim over the coasts, volcanoes, deserts, mountains, rainforests, lakes, savannas, nature reserves, forests, mountains, rivers of Hawaii, Turtle Islands, Abya Yala, West Africa, East Africa, the Indian subcontinent, Papua New Guinea and the islands of Vanuatu and Kanaky to seek a new place in the order of time; to create a new place for itself on the world map. Likewise, they also crossed the Brandenburg Gate, Red Square, Marina Bay, Kowloon Bay, the Sensoji Temple, the Harbor Bridge and the Waterfront, which were no longer ahead of Samoa, but behind this archipelago. Samoa was now ahead of them. It had moved from one side of the dateline to the other and thus became one of the first countries to from thereon enter any new year.

Samoa had exchanged the back seat for the front seat. As an immediate result, a Thursday (December 30 2011) was followed by a Saturday (January 1 2012). This radical erasure of time also meant that for this particular week, the five-day business day-cycle introduced by industrial capitalism and globalised by colonialism was drastically shortened. It turned into a four-day work week. While local employers and traders were naturally enraged by the elimination of hours of production, workers, on the other hand, were delighted. They were compensated by the government for their missing wages. The long-term consequences of this decision were however also more sensible to capitalists’ needs and interests: Samoa was no longer chasing behind others. They preceded them. They were no longer the past of everyone else. They had become the future of everyone else.

The date line Samoa decided to autonomously move was at the time hundred twenty-seven years old. It was thus also older than Samoa had been as a modern independent state. The line was drawn in 1884 during the International Meridian Conference in Washington D.C., the European settler-city built on the land of the colonised Anacostans. During this worldmaking conference, twenty-five states, most of them colonial empires and settler-colonies, decided upon the creation and location of a “prime meridian’’. In arbitrarily doing so, they also decided what maps would turn out to look like: where their centers were made to be and where ultimately also their peripheries were conceptualized to be; where the world began and where the world ended. The imperial consensus for a prime meridian fell on Greenwich, England, which henceforth became longitude 0, to which all other locations and time zones should from thereon refer to. Greenwich, England, became the starting point of the world from which the surveying of this world took place; from where Europeans started to name and frame this world. It would set and hold a monopoly on time and space that would soon entail the entire world by way of imperial expansions. It was to control the rhythm by which every place, every living being, and every clock hand would from thereon be forced to move by. This enforcement of European-capitalist time did of course not come as a letter of recommendation to the colonies. It came under duress: hand in hand with the destruction of lives, lands and times. Other times. Times that refused the rhythm of European capitalism. Times that pointed to different relationships to the skies, lands, living beings and labour.

Europe’s attempt to universalize the world was truthfully put the attempt to Europeanise the world and was directly linked to the needs of European industrialization. With the help of different technical ‘innovations’, including the infamous clock, the world began to shrink for Europeans in its distances and temporalities. As a result, Europeans were able to better subdue and reorganise these formerly distant natures, people and cultures according to their own industrial needs.

The flipside of longitude 0 was longitude 180. It from thereon marked Europeans’ other side of the world by way of a line defined by Greenwich, England. This decision on where to place this line was made in the absence of any beings inhabiting this part of the world. Yet Europeans declared their habitats to be the host of a line they had no indigenous relationship to, nor space and need for. This imperial line appeared as an artificial time hole that was believed to swallow time when being crossed. While there was no physical change of nature to be felt and seen anywhere near this place and space post-conference, European clock hands still fooled humans to believe that one would, depending upon direction, either lose or gain time across this line. This was particularly detrimental for people like Samoans, who from thereon were made to believe to live at the crossing of days. The placement of longitude 180 into this oceanic region followed a very European logic: the region was physically so distant to Europe that the consequences of such a time hole could not be felt in Europe and by Europeans themselves. For Europeans, it was no issue to create such potential chaos in and for a different part of the world. According to them, this region anyway contained more water than land, more waves than people, more islands than large land masses, and more beaches than raw materials that could be of use for Europe’s industrialisation of the time. By reinforcing the idea of a global periphery, a place where today meets tomorrow, yesterday meets today, where time virtually collapses, Europeans were able to stabilise the myth of Europe being the very centre of the world.

As expected, Europe was, of course, largely spared by the complications produced by this time-space collapse. And yet, by further establishing a capitalist and colonial order that would allow for a more efficient extraction of labour and raw materials from the colonies in the direction of the metropolises, it mainly served European interests. Europe’s attempt to universalize the world was truthfully put the attempt to Europeanise the world and was directly linked to the needs of European industrialization. With the help of different technical ‘innovations’, including the infamous clock, the world began to shrink for Europeans in its distances and temporalities. As a result, Europeans were able to better subdue and reorganise these formerly distant natures, people and cultures according to their own industrial needs. Likeso, they were able to throw them out of their autonomous times into European-Christian calendar. This displacement of indigenous people from their own times was of course also a physical and emotional displacement from their autonomous relationships to the sun, moon, lands and waters.

Six years after this detrimental time-space decision was decided for this region in a faraway European settler-colony, the same European empires that redraw maps were now threatening this region with total colonisation. Samoa, like many islands of this region, had for long been spared from being formally colonised by European empires in parts thanks to the physical distance it held to Europe and its many machines. In the late nineteenth century, when Europeans closed down upon whoever remained free from their terror, the archipelago also found itself on their target line. In the west Samoa had been surrounded by the Germans and the British. In the ‘east’ their kin, European settlers from occupied Turtle Island, were similarly aiming to overrun the archipelago. Samoa had found itself in a deadlock. While Europeans from the west offered no alternative to colonisation, Europeans from the east offered an ‘escape’ by way of a change in time. If Samoa was to move from the western side of the dateline to the eastern side, closer to their own settler-colony’s place in time, they’d be given favourable trade relations with the settler-colony and thus be able to potentially fend off formal European colonisation. In the hope of avoiding further foreign subjugation, the then-still independent kingdom decided to give in to this pressure. They shifted towards the eastern side of this newly created European date line. In taking this desperate step, Samoa moved, at least timewise, away from the side of the world it shared social, cultural, economic and geographic proximity with towards a distant landmass it shared little with but, from thereon, temporal proximity.

Despite this trade off, Samoans’ hopes for independence and freedom from European reign were in vain. Seven years later, the territory was no more just an involuntary trading partner of the USA, but also formally colonized by white rulers. The archipelago was divided between the German Reich to the west and the European settler-colony USA to the east. While the western part was to become Deutsch-Samoa, the eastern part consequently became American Samoa. Though the island territory was now divided and governed by two distant capitals, this political division didn’t challenge the archipelagos’ formal date line. Both parts were caught in the same artificial time and thus also on the same place on the date line. When the Germans lost their colony to the British settler-colony New Zealand in 1914, the nearby British settler-colony administered for the next forty-eight years this newly conquered territory on behalf of the British Crown. Deutsch-Samoa was soon after renamed to Western Samoa Trust Territory. Meanwhile little changed for the eastern part of the archipelago. While its counterpart changed status from colony to independent state in 1962 and renamed itself in the wake of it, first as Western Samoa and later as Samoa, the eastern part remains up until today an US-American colony.

When decades later independent Samoans decided to move their clocks, it wasn’t just their attempt to undo a form of temporal injustice. It was more importantly an attempt to alter their place on the map and with it their direction of looking. The government’s decision to relocate the independent part of the country by almost twenty-four hours was indeed primarily motivated by an economic calculus rather than a political one.

When decades later independent Samoans decided to move their clocks, it wasn’t just their attempt to undo a form of temporal injustice. It was more importantly an attempt to alter their place on the map and with it their direction of looking. The government’s decision to relocate the independent part of the country by almost twenty-four hours was indeed primarily motivated by an economic calculus rather than a political one. And it followed a similar leap in time made by neighbouring Kiribati in 1994. Likewise, Samoa hoped that this time change would give them trade advantages with their geographic neighbours to the east, who were anyway closer by distance and economically more relevant to them than those in the west. Though this intervention didn’t break the colonial logic of universal time but only renegotiated it, it was still politically radical. As a small country with a population of less than 200,000 people, Samoans decided to centre their own interests, rather than those of more powerful strangers. But perhaps a more important argument for this change in time was to be found elsewhere.

Following decades of colonisations, displacements and imperial extractions, today more Samoans live outside of the archipelago than on the archipelago itself. Neighbouring Aotearoa alone is, for example, home to up to 180,000 Samoans. Almost as many Samoans as on the islands itself. Samoa’s geographies are therefore hardly limited to its own national territory anymore. They have extended with every Samoan who had to leave the islands for different reasons. The nearby date line complicated these transnational relationships. The large Samoan diaspora in Aotearoa was up until 2011 not only separated by 3270 km from their homeland, but also by a severe time difference of almost twenty-four hours. The temporal distances did not correspond to their spatial distances and, above all, their emotional distances. It embroiled the rhythm of life of families who lived at different ends of the day - who neither shared hours and hardly ever days before December 30, 2011. Likewise, many Samoan families had to wish each other a ‘Happy New Year’ with a delay of almost twenty-four hours. When December 31 2011 was disappeared from the calendar, this time boundary shifted further east. Within seconds there was no more than an entire day that stood between them, but only a few hours. Samoans found themselves on the other side of time, on the other side of the day and the other side of the world. Now they were more in tune with the majority of their own people who lived to their west. This temporal repatriation however, also created new dividing lines. Unlike their independent kin, their occupied kin in American Samoa stayed behind in time. They were left behind in a temporal as well as political past. Though the distance between the closest points of independent Samoa and US-American-colonised Samoa are only seventy kilometers, both shores slipped at the end of 2011 away from each other by almost twenty-four hours.

Whose past is (now) whose tomorrow?