Mommy Say Something to the Camera, Mom! (2021) installation: 3-channel sound, aquarium, and film projection, Kuvan Kevät. Photo by Theo af Enehielm.

Sepideh Rahaa (b.1981, Amol) is a multidisciplinary artist, researcher and educator based in Helsinki. Through her practice, she actively investigates and questions prevailing power structures, social norms and conventions while focusing on womanhood, storytelling and everyday resistance. Currently she is pursuing her doctoral studies in Contemporary Art at Aalto University. Her practice and research interests are representations in contemporary art, silenced histories, decolonisation, Intersectional feminist politics and post-migration matters.

I entered Caisa’s theater in silence, where the film program of the Latin American Film Festival Cinemaissí was already running. The program was thoughtfully curated, and a meaningful thread ran through all of the films. There, I came across Paola Fernanda Guzmán Figueroa’s film “Mommy, Say Something to the Camera, Mom!”. The fifteen-minute-long film did not give me a chance to blink; I could not stop thinking about its dreamlike atmosphere that traveled back and forth between the present and past moments through the familial archives and present-time footage. Paola’s attempt to reconstruct her past in relation to her current search for answers as to why she is thousands of kilometers away from her family captivated me. What you’re reading is an exchange between Paola and me in which we try to understand her working processes and inspirations for creating this work in greater depth. The film was first exhibited as part of her graduation installation at Project Room Gallery, Kuvan Kevät.

SEPIDEH: Based on what you told me, first, you came to Finland as an exchange student in the set design department in Aalto. And later, you decided to study for a master’s degree at the Academy of Fine Arts. I recall that since 2017 there has been a tuition fee in place for non-European students who want to study in Finland. Can you tell us more about your story?

PAOLA: Of course, everything becomes more difficult when you need to pay for your studies, even though there are scholarships. It’s something that you need to take into consideration. That’s why I decided to apply for my bachelor’s and master’s degrees in 2016. When I arrived in Finland in 2013, I came as an exchange student in the Film and TV department in the Scenography and Production Design program. I thought about applying to Aalto University because my sister studied for her Master’s degree in the Creative Sustainability program at the same university. I was amazed by the opportunities; I could design something, and we could build it on a huge scale with the colors and materials that I planned. I was like, “What is this?”. Following my exchange, I decided that I wanted to focus my studies more on the fine arts, which were the focus of my previous studies in Colombia. I wanted to make films, video art, and installations. Later on, I decided I wanted to apply to the Time and Space program at Kuvataideakatemia; it had all the subjects I was interested in studying.

Your work at Cinemaissí made me think a lot because I could relate to it so much without reading any texts or knowing your position as an artist. There’s strong visual language and narrative in there, and the silence has worked extremely well in your work. To make this work, you revisited your family’s video archive and had some conversations with your family members. Can you open up a little bit? What was your process like?

When I moved away, I started looking for family material. Being away from Colombia made me feel the need to answer several questions: Why am I here in Finland? What has brought me here? I know that partly it was about the opportunities, but it was also about following my sister and still being together with the family. I embraced my connection to them even more. I live in a completely different culture in Finland and feel very different. And that is why I wanted to research more about why I feel different and why most families here are not as connected as my own family. Anyways, all these questions have brought me deeper into this idea to research more about why we are so connected in our family. I started studying my family dynamics; for instance, I noticed that after I left home, my parents had a stronger relationship, which made me completely happy and curious at the same time. My parents divorced when I was 14, which was a hard time for my siblings and me. After a few years, they reconciled. Since then, “family” has become a stronger symbol for my life and art.

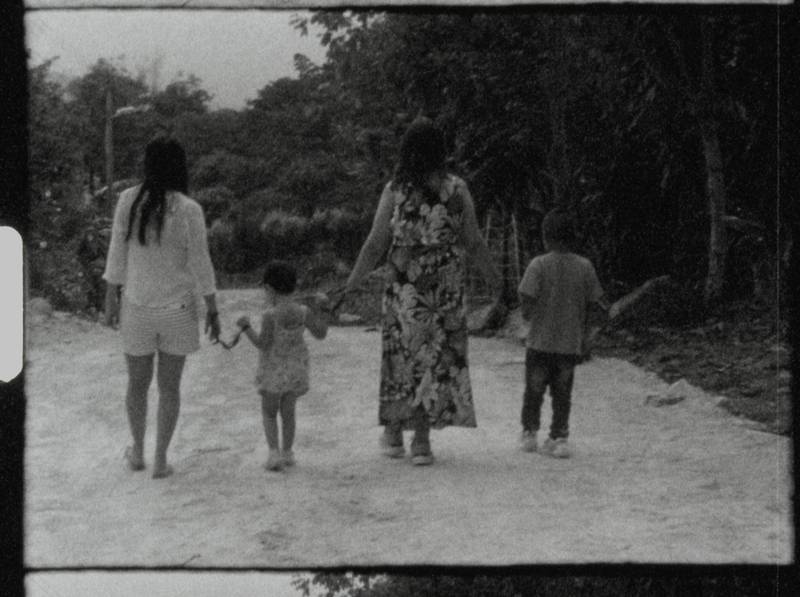

Still image of “Paola: Mommy Say Something to the Camera, Mom!”, Shot made by: Luis Eduardo Cruz.

So the working process that you are talking about was to understand how the connection between your family members worked and how you became closer?

My parents’ message has been that we should always be together and help each other. For instance, my sister and her husband hosted me here in Finland. I often followed the relationship between my parents and wanted to know how they were doing. I had a fish aquarium at home. The first time I visited my parents, I saw that the aquarium was more beautiful than when I left. I noticed this change and thought something was going on. My parents were closer, and it seemed that the aquarium became a representation of us, the children. They were really into the aquarium. Later, I interviewed my dad about the aquarium and the fish, and he explained how he and my mom took care of it, bought new pumps, and cleaned it. After leaving them, I got the first images: the aquarium and how the house was changing. Although we were not coming back to live with them, they tried to keep the three rooms. They tried for some years, and it is challenging to think about. For them, the aquarium became me. Since then, nine years have passed, and now the aquarium doesn’t exist physically. For me, the aquarium has come to represent our relationship. The aquarium doesn’t exist as a physical object, but it has become a metaphor for life in my film. I work a lot with the idea of motherhood, with lines, with departure, and then family material. Because we, as foreigners living in different countries, and even more so in Finland, come from diverse cultural backgrounds, we often ask questions about family relations and also embrace that kind of question.

I moved to Finland 9 years ago, and I have been separated from my family since then, only visiting once a year. In general, there is separation, and this intense feeling of longing has captivated me since I moved here. Once I arrived in Finland, I started looking at my past, memories, and family from a distance, so observing the past from another place made me understand our relationship’s meanings and importance. In Finland, family relationships are not as close as in Colombia. Surely, that has been one of the aspects that have affected me. I miss them and the past, but I know I cannot go back. Even if I went back physically, the reality would not be the same; people change, and situations change. The only way forward is to continue to create my art.

I’ve worked myself with family archives at times, it can be fun and difficult at the same time. How was it for you to work with the family archive?

It was very emotional because I was nine years old when I shot the material, and when I saw them again, I was twenty years old. There was a significant change between these eleven years. When I discovered that it was me, a nine-year-old, filming my dad, mother, and grandmother, it was huge because I acted like a filmmaker, following everyone and asking these questions, which you can see in the film. When I found out that I was actually the one who was filming and asking questions, I thought this was actually Paola of the present talking with Paola of the past. Can you do that? Yes, I did that! Revisiting the archive and seeing many relatives in the video, many of whom have passed away. To see them sending a message to my mom on her graduation day.

I come from a different cultural background and geography, yet I could so much relate to the moments in your film where everybody was sending congratulatory and admiring messages to your mom or when you were holding the camera; I did the same, but I was older than you.

It is really beautiful that the parents allow you to use the camera. I have seen that in some families, parents are protective of objects, but my parents were always very trusting. I was nine, and they did not correct the way I used the camera. They never told me, “Don’t break it, Paola,” but instead, they trusted me as a child.

One good thing about working with close family members is that there is so much intimacy and trust that they forget about the camera and mostly treat you as you, not as someone holding a camera and filming them. My graduation piece was a video called “The Distance,” which I made with my mother. She went through the family archive in the albums. She became extremely emotional when relating to various photographs, even kissing or destroying some. Later on, I heard about Mona Hatoum’s video “Measures of Distance,” and although it was after I finished my work, it affected me and stayed with me. Because while the contents of our works differed, our relationship with our mothers was central to both. What I want to ask is: many artists have worked with family archives; are there any artists who inspired you?

Yes, there are. Chantal Akerman’s film “News from Home (1977)” was one of the artists whose work impacted me. She made it in the 80s, and there are long shots from the metro or streets in New York City. There are scenes of empty streets or people buying things in the shops. In this film, we never see any faces; we see New York City and hear a voiceover from the director reading the letters that her mom has sent to her while she has been away from home. And it’s funny because I visited New York and checked the metro and realized that it was exactly the same and that nothing had changed from what I saw in her film. It is important because everybody in the metro is in their own world but also has so much to say.

Another artist is the Colombian filmmaker Ana María Salas. She kept a diary called “Fronte al Espejo/In Front of the Mirror” while living in Paris. This was beautiful to see when I moved to Finland, and it gave me the strength to take the camera in my hands and film my life in Finland and Colombia. Other artists who inspired me are Jean Painlvé and Genevieve Hamon. They were underwater filmmakers who worked between the 1950s and the 1970s—their films challenge nature as fiction. My childhood has been one of my most valuable references. With my siblings and parents, we watched independent cinema in the center of Bogotá. We saw plenty of films from everywhere worldwide, which meant a lot to me. We watched movies by Kiarostami, “Where Is the Friend’s House?” for example, and a magical film called “Microcosmos,” in which tiny insects had a beautiful and energetic life.

Through actions such as transporting an aquarium that contains my hair, I give air and life to an inanimate creature. In this piece, I explore the emotions of longing and the desire for reviving past life. Time travel, Paola and her father fixing the aquarium in Bogotá. Photo by Juan Figueroa García January 2019.

When I read your short text regarding your graduation installation work, you mentioned three crucial factors: family, migration, and motherhood. Can you explain what their relationships are in your film?

These three topics have started the process of following my family in Colombia. It is the question of being separated from them while being very connected to my culture and embracing it more. Family is essential for the whole work, and it is the frame around the work. Then there is the question of migration: I am here and will never fully become Finnish or remove my Colombian identity altogether. Because it comes with me, I will be forever a migrant, and Finland will be my second home, where I will develop an important part of my life. Migration is connected to this and the idea of family. And motherhood is the topic that closes this work. The idea that I am here (in this world) primarily because of my mother, who has been the face of everything, is another reason for connecting this family. She has been the rock for us, even my dad. My mom supported my dad. She has carried so much in her life, and I am very grateful. She is the one who faces all the problems, and she is the protagonist of the story. One of the stories I recall from Finland is the trip to Venezuela, which is at the beginning of the film. We went there, and it showed that my mom was leading us to Venezuela and then taking us back to Colombia. I remade this point in my film; there is a scene where my mom, I, and two other kids are moving forward. I spend a lot of time playing with the present past.

And hair? It is a powerful medium in your film, both visually and conceptually, even philosophically. Hair, aquarium, and womb—why these three?

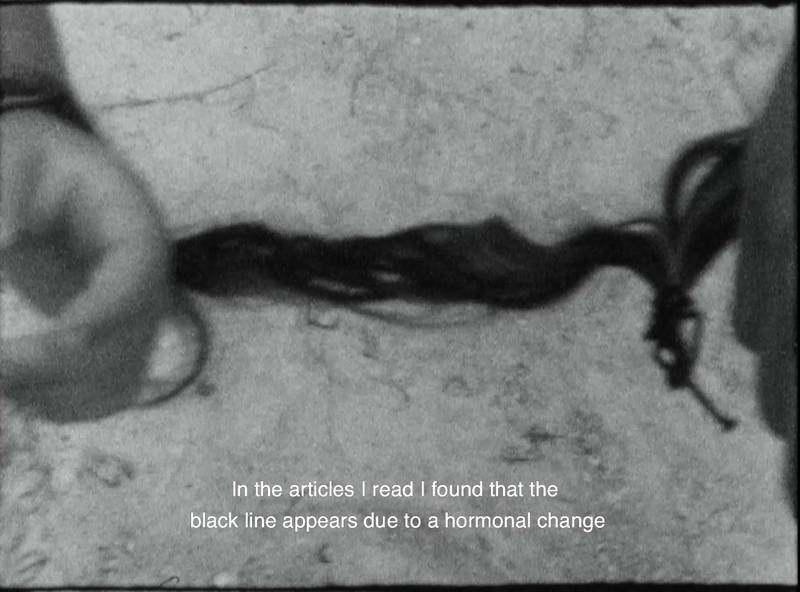

Hair is a critical object in my artistic research, both as a material and as a concept of investigation. I’ve been saving my hair since I moved away from Colombia. It happened almost unconsciously, so I kept it as an experiment for my video art projects. Later on, I started finding different meanings. Hair became a material to reconnect me with my family’s past; it became almost like a film emulsion carrying lots of information I wanted to develop and find.

Hair is an element that resembles plants in several ways. Although it is not a living object, it grows similarly to plants and carries infinite memories that could serve to attribute life to it. Hair has a place in memorials, rituals, and magic and has an ambiguous relationship with the rest of the human body. I am interested in the uncanny quality of hair as an external material when separated from the body. I wanted to give it life after cutting it and separating it from my body. But how? This was when I realized water could serve my purpose. Water symbolizes life, so I wanted it to be present in this piece. Through a hose conducting air to an aquarium with water and hair, I could give life to the “dead” hair. This aquarium became the script. The expansion started happening when I left Colombia. Even though we are thousands of kilometers apart, we will always be in the same aquarium. The only difference is that it is becoming bigger and bigger, and new generations are being born and joining the same aquarium.

Still image of “Paola: Mommy Say Something to the Camera, Mom!”

In the film, as an audience, we could see the attachment of each kid to the mother via different colored strings. “The relations among us have transformed, but the cords are not weaker.” You talk about these relationships and the connection through cords as a driving force; can you elaborate more on this?

I discuss my mother’s journey back to Venezuela while carrying all three of us children with her. We were all kids, and my parents had to devise a creative idea to ensure we would stay by her side. Then, my mom decided to use strings or cords attached to each of her wrists to keep my siblings connected to her and out of danger. I was one year old, so my mom carried me attached to her body. When I heard about these cords from my mom’s narration, I found that everything made sense. Those strings holding us to her had been present throughout our lives as a family in an emotional way. The strings are not material anymore, but we all know they exist. We all know they keep us safe and then hold us together despite the time and distance.

In your film, the absence of voice, possibly a man’s voice, is powerfully putting the pieces together; actually, it is perfecting the aim of the narrative around women in the family, basically the mother and the daughters. What do you think? How did you come up with the idea?

Yes, you are right. In that part of the film, the speech was given by my dad, but we cannot hear his voice; we can only read the subtitles. I wanted to have a silent moment in the film. Silence, to me, is a sound; it strongly shapes the narrative. In addition, it gives importance to the story. For me, the audience needed to read this speech. I did not want to use my dad’s voice since the speech was already so strong because he referred to my sister (whose birthday we were celebrating) and my mother’s graduation. I also wanted to connect the audience more with themselves by leaving that part without sound. I tried to make it more personal. This silence was so powerful in the cinema, we could feel the need to question ourselves. In addition, there is always something happening in our minds when we remember someone. Even though we don’t hear their voices, we can listen to them in our minds. This is what I wanted to happen.

Mommy say something to the camera, mom!, Paola Fernanda Guzmán Figueroa