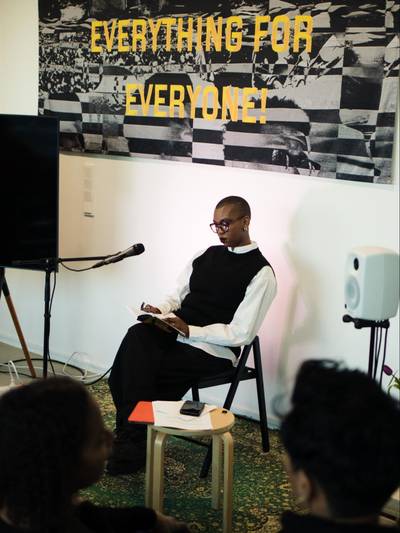

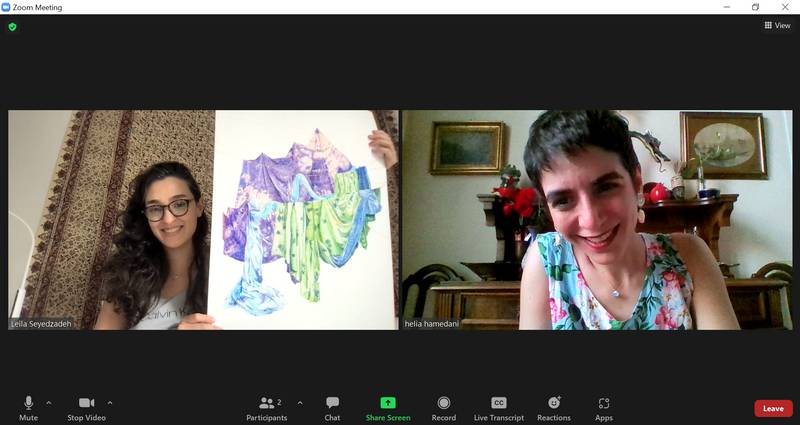

Helia Hamedani is an independent curator, working between Rome and Tehran. She is particularly interested in the Intercultural field and collaborates with nonprofit cultural associations. She is a Phd student of Art History at La Sapienza University of Rome. Her doctoral research of the studies and visions of Ruyin Pakbaz, intends to narrate the state of Iranian historiography of art over the last 60 years. Hamedani writes for magazines on contemporary visual arts in Iran and Italy.

Leila Seyedzadeh (b. 1986, Tehran) is an Iranian interdisciplinary artist and curator based in New York. She adopts a poetic and semiotic approach in her work by displacing memories and landscapes. I got to know her work on social media and immediately became interested in her feminine approach through collages with fabrics and how her work was inspired by ancient paintings in Iran called Negārgari. In some of her works, she starts from the specific composition rules of Negārgari, removes human figures, and enlarges nature to give a poetic and symbolic touch to the natural and pictorial space. This places her work at the crossroads between painting and sculpture. Despite using Iranian texture and technique, her work points out universal archetypes beyond the artist’s personal experience. Her practice combines monumental concepts with subtle and detailed visual elements. She creates fragmented meanings that the audience should decode from time to time through the references she indicates.

Leila is a recipient of the H. Lee Hirsche Prize in 2019 and the Soma Summer Fellowship in 2018 at the Yale School of Art. She graduated from Yale School of Art in 2019 with an MFA in Painting and Printmaking and a BFA in Painting from the University of Science and Culture in 2014. Apart from her solo exhibitions, she has participated in several collective shows in Iran, the U.S., and Europe. Today, in addition to her artistic research, she teaches at the Fine Art Department of Pratt Institute, NY.

HELIA: Leila, you started as a painter. In recent years you have been painting with fabrics, dyeing your surfaces, drawing lines by sewing and collaging different clothes, and creating experimental spaces. Since when and why did you choose fabric as the primary material for your work?

LEILA: I began using fabric within my fine art practice in 2015. However, I have been immersed in textiles my whole life, and my mother is undoubtedly the main inspirational force behind this incredible experience. Our house was always full of fabrics: curtains, mattresses, sheets, and many of my mother’s Chador Namazes (prayer veils). As children, my brother and I often made a big tent in our bedroom out of my mother’s chador that almost occupied the entire room. I was excited to experience a different space between the wrinkles of the fabric, as if entering another world. What surreal joy to lie down on the carpets and stare at the floral chador ceiling.

Another memory that impacted my relationship with fabric was my mother soaking white curtains in indigo dye, a practice traditionally passed down from mothers to daughters, transforming the white fabric into clear blue hues. Afterward, she would hang them to dry in the wind.

It’s not surprising then that I made my first installation by upcycling old sheets and curtains with the help of my mother, who taught me how to dye, sew and mend textiles. I want to credit my mother, a traditional housewife who mastered countless skills (parts of which were passed on to me). Yet, like many women, she was never formally paid for her work.

Suspended pink mountain, 2017, hand-dyed cotton cloth, found cloth, rope, 15 x 11 x 7 in, 2017

You are also influenced by Negārgari (incorrectly called Persian miniature) and their different rules from the Renaissance perspective in defining the landscape. Can you tell me how it influences your work to create alternative spaces?

My works contain various influences from Negargari traditions. I first create compositions on paper as the basis for my textile paintings and installations. I gradually create the shapes, followed by layers of colors and patterns. In particular, I use the flattened perspective, and bird’s eye views are iconic Negargari paintings. I also am influenced by the color palette and textures of this tradition that I render into 2D and 3D works of art. For example, the mountains are vertical in my textile paintings, but the rivers and valleys are seen from a bird’s-eye view. In my installations, the mountains remain vertical while I incorporate objects, such as Persian carpets and Jajims (lightweight nomadic carpets), to maintain the bird’s-eye view in the 3D installations. Viewers only break the initial flattened perspective by entering and walking through the installation.

Suspended mountain, 2022, fine liner color pen on paper, 23 x 29.5 in

Suspended pink mountain, 2022, fine liner color pen on paper, 22 x 23.5 in

Lately, you have moved from three-dimensional installations with fabrics to two-dimensional works to the pictorial surface; what are the motifs, and what are the similar or different characteristics of these works?

In these paintings, I use a visual poetic language that focuses on indirect reference and landscapes immersed in placelessness. These landscape “paintings” are created using a variety of hand-dyed fabrics from Iran, including fragments of chador namaz, Termeh (Persian handwoven cloth), silk and cotton textiles, and delicate fringe.

Influenced by Negargari, I use multiple visual elements that hint at mountainous forms and integrate non-western compositional techniques, relying on a layering of patterned shapes rather than a depth of vision to convey mass and space.

One of these two-dimensional paintings has double sides. I have interwoven fragments of a mail receipt sent by my brother with visible words that include Tehran, Iran, and New York, USA. By weaving this mail receipt into a piece of fabric and creating a hill with a mountainous view, I complete the painting with a piece from home. And I refer to the duality and conflicting nature of my identity.

On the other side of the painting, the colorful sewn threads have become a mountain range that evokes a geographical map of Alborz. In addition, it’s inspired by flag embroidery displayed in Iran during the annual Ashura festivities.

Suspended mountain, 2017, hand-dyed cotton cloth, found cloth, rope, 13 x 9 x 5 in

An absent view, 2020, hand-dyed cotton cloth, hand-dyed single-ply cotton rope, found cloth, hand-dyed fringe, ribbon, hand-woven Persian Jajim, 18 x 9.5 x 12 ft

You have also appeared as the curator of a collective exhibition: The sky is higher here (Transmitter, 2022). What were you looking for in this dialogue with other artists, and what did you discover as a curator?

The artworks featured in the group show referenced the subtle boundaries between what is free of the physical and what is not—how can we mirror what we find in the sky and what it reveals in us? Various mediums, such as painting, textile, photography, textile weaving, and mixed media, explored the vastness of the sky and found refuge in this great space with no borders.

One of the first things that got my attention from day one of my immigration experience to the USA was that the sky is higher here than what I felt back in Tehran. I still don’t know if there is a scientific reason behind it or if it is just me seeing the sky this way in North America.

Later, I visited Mexico City and Toronto, and I noticed the sky was high and vast. And when I traveled back to Tehran, I looked carefully and saw the sky was not the same, and I tried to understand why it was lower there. Later, I wrote a poem about how I see the sky, how it has different blue colors in other places, and the challenges in my journey. And this poem was the core of this exhibition. And by gathering these pieces and the stories, each artist transferred regarding my poem The Sky is Higher Here as their source of inspiration. Interestingly, when I presented the idea and shared the poem with artists, they connected quickly and got inspired to create these artworks.

Each artist in this show explored different materials to create a body of work about the theme of the sky. One of the artists spoke about the grief of losing her sister, which was reflected in the blue sky with fragments of collage bodies as the idea of becoming free of the physical, becoming formless. Another artist talked about the sky of the east and west coast of the USA – although they are in opposite directions, they can both still generate the same type of peaceful feeling. Our relation to scale and time also shifts when facing these landscapes.

We are different, but, at the same time, we all go through ups and downs in life, immigrate to a new place, or travel to different landscapes, and everyone can share these in their way. Being in New York among a diverse group of artists from around the world inspired me to listen to stories that speak about the same content but come from different places – from Iran, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, and the USA. These artists shared their ideas through painting, photography, textile, mixed media, and more. I wanted to connect life’s challenges with a natural element; in the end, the sky was the best one that reflected all of them without any limits.

By studying the Moon and the stars and connecting our mood to how we smile or cry, we are still trying to make sense of the sky surrounding us. Despite the insurmountable distance between Earth and the sky and its defiance to be understood, these artists searched to make it accessible and deeply familiar. We know that only something as magnificent, shapeless, and borderless as the sky can hold the sum of all our heart’s grief and hopes without ever pouring over.

All I remember (front), 2022, hand-dyed cloth, handwoven Persian textile (Termeh), mail receipt, found fabric, ribbon, fringe, wood bar, 25 x 56 in, double side painting

Memories from home, 2021, hand-dyed silk & cotton, found cloth, ribbon, fringe, wood bar, 19 x 48 in

I read in an interview that you began writing poetry after immigrating to the U.S. I’m curious to know how words could help you in your visual practice. If it’s ok for you, I’d like to ask for one of your poems for the closing of our interview.

Back in 2018, being in Mexico City helped me perceive and imagine the mountain from a completely different perspective. In Tehran, the mountain range is seen in the city’s background; we are at the foothills of the mountain. Mexico City was built on the top of the mountain, and it has an altitude of 7,200 feet above sea level (whereas Tehran has an altitude of between 3,000 to 6,000 ft). Mexico City ignited a curiosity within me to delve deeper into ideas of altitude and gravity and to explore their intense physical effects on our bodies. I was inspired to write a poem about this experience called Gravity, which became the source of new works. I began thinking about the bodily experience of physically rising to the top of the mountain and the effects of increased altitude in tandem with the feeling I had when I first arrived in the U.S. I was often stuck going between translations of Persian and English.

Back in the U.S., I started experimenting with the frequency of my voice in Persian and English, transforming it into a mountainous visual landscape. I etched the frequency onto glass, yet the lines can only be seen through a shadow cast on the wall, like a sound drawing. This work is called The Landscape of my Voice, and it reflects the duality of my life in the U.S. and my memories of home, the tangible and invisible spaces of my current reality.

East River

The sun rises where you emerge

Flowing down, you divide both sides

Bridges connecting your banks

Ships overturn your waves,

You pour into the North Atlantic Ocean

Several days later,

In the far away land

You arrive home

Where the rivers weep on their bed of loneliness

You flow through the Alborz mountains

When you reach Tehran, you rain

My mother is sitting by the window,

gazing out at the rain

I wish I were flowing in you, oh the eastern river.

Becoming landscape in a landscape then disappearing, 2018, hand-dyed cotton cloth, site-specific

Far away, hand-dyed cotton cloth, 2022, found cloth, ribbon, wood bar, 51 x 30 in