Illustration: Yara Bamieh

Shayma Nader is a curator and researcher born in Jerusalem. Her research focuses on anticolonial, antidisciplinary and land-centered imaginaries and practices. She is currently a PhD candidate in artistic research at ARIA at Sint Lucas School of Arts (KdG) and University of Antwerp.

1.

Some 80 years ago, there was a ghoula1 waiting by a well for my great uncle, Husni Salim Albess. She was combing her long black hair and watching her reflection in the water until he passed on his horse. In one version of the story, he was going from the village of Saidoun2 to Abu Shusheh3 to mediate a dispute. The ghoula was less charming than she thought. Her eyes were vertical, and she had hooves instead of feet. Upon setting eyes on her, Husni fled to Abu Shusheh in a fright, as the ghoula chased after him. Husni never told us what exactly happened after that. All we know is that he reached the village of Abu Shusheh. He passed out for three days afterward - perhaps from fright, perhaps from exhaustion. When he woke up, he would tell everyone his story.

Husni would eventually die while fighting for Palestine in 1948.

Another legend from my mother’s side of the family tells the story of Hasan Jaber [Abu Mustafa], who was riding home drunk one night when a hyena softly brushed against his donkey. The donkey was petrified as the hyena sprayed them with its enchanting piss, and Hasan was spellbound. He may have dismounted from the donkey, or maybe he was knocked off, but every version of the family story has him running after the hyena frantically, calling it yaba, yaba [father, father] until the hyena carried him on its back into a cave. He hit his head on a rock at the entrance of the cave, and the blood gushing from his wound woke him up from the spell. His fate is left unknown, and the subject of much family speculation.

in al-Rawha, March 2020. From his Facebook account](/images/5tTjMkP-Q0-800.jpeg)

in al-Rawha, March 2020. From his Facebook account](/images/S-3F9y-Rbf-32.webp)

Photo by Mohammed Mustafa Mahamid in al-Rawha, March 2020. From his Facebook account

These “impossible” tales have become part of the family lore, affirming a multitude of worlds that existed within, in parallel - or at the edge of ours. Nurturing, clashing, and shaping each other. These fragments of fictitious memories are told as one small part of a pre-1948 history and space that went temporarily extinct along with its human and non-human inhabitants, but their memory and descendants remain stubborn as hell. Facing multiple, relentless programs to erase their presence, and erase the erasures, Palestinians still pursue and dig up worlds and universes triggered by their presence, by a Roman wine press carved in stone, a fern near a spring resembling a ghoula’s hair, or the cry of a ghrairi [honey badger] calling from the depth of time.

2.

“Atop a mountain covered with forests of pines, cypresses, and oaks, neon lights shine from an Israeli settlement, which they call Halmish, and we call al-Nabi Salih. The lights are cold and revealing, and are engulfed by barbed wires. The settlement appears to be hanging in space, perhaps because of the light, but also because it is yet to touch the earth or history.” Among the Almonds, Hussein Barghouti

A few months ago, I drove past horsh um safa - a little wooded area a lot of Palestinian families visited for walks and excursions before the second Intifada4, near the settlement of Halmish. The wood, which was once an olive and fig grove, was transformed into a pine and cypress wood to provide cover for British soldiers. I wondered why we had stopped going, only to be told the rumor that the Palestinian ranger guarding the wood had been slain by Israeli settlers in 2008.

As is the case with most settler-colonialisms, there is always a determination to seize the maximum amount of land and destroy all that remains or any access to it. The landscape is flattened, soil turned upside down, caves and springs blocked, and colonial (infra)structures, highways, and tunnels slice through the terrain. What is left is besieged and transformed, turned into stone and marble mines sustaining the ambitious world-building of the settlement leaving unsightly holes in disoriented hills.

A settlement, in all forms, is a crawling space. It swallows and shatters im/material lives, routes, and worlds above and within Palestinian valleys, woods, and hills covered by oak, pistachio, carob, strawberry tree [qayqab], azarole, sumac, and almond for centuries. As is the case with most settler-colonialisms, there is always a determination to seize the maximum amount of land and destroy all that remains or any access to it. The landscape is flattened, soil turned upside down, caves and springs blocked, and colonial (infra)structures, highways, and tunnels slice through the terrain. What is left is besieged and transformed, turned into stone and marble mines sustaining the ambitious world-building of the settlement leaving unsightly holes in disoriented hills.

In the Wretched of the Earth, Franz Fanon tells us the colonial world is a world “divided into two.” (2004). Land seizure permits the creation of a world that affords differentially distributed possibilities and sensibilities of spatial practice. Thus, the settlement is not only an attack on senses and horizons; the settlement — detached from the earth it occupies and seemingly hanging in space — produces roads encircling and passing over and under Palestinian villages rendering them invisible, inaudible, and insensible to the settler, yet connects and opens horizons for the settlement. The settlement’s mission is not only to empty the land of anyone or anything that challenges its presence, but it is also to suppress any encounter between anything daring to exist outside its logic (human-human, human-animal, human-wild plant, non-human-non-human). In this division and obstruction, I wonder if there is space left for the ghoula to comb her hair, away from the settlement’s blinding lights or how many caves are left for the hyenas to return to. I also wonder when the time will come again when we think we hear the sound of a ghoula rubbing ground salt under her breasts or the shouts of a drunken man chasing after a hyena.

Hussein Barghouti explains how the مكان makan [place] is derived from the root مكن makana [to remain], and connects to the capability امكانية imkaniyya and mastery تمكّن tamakkun5. Similarly, it shares its root with كان/كون kan/kawn [universe] and كائن ka’in [being]. This being in and mastering of a place and its worlds/universes reveals its enchantments in the details, the embeddedness brings an awareness and a capability to position oneself in time and space and an ability to name in relation to the surroundings. The naming bespeaks a mastery [tamakkun] of the relationship with the place [makan] and its beings [ka’inat].

Sometimes names trigger a memory; these names of villages, springs, woods and valleys were derived from experience incomprehensible to settlers; Ein ghazal (gazelles spring), Beer al-Sabe’ (the lion’s spring) Deir al-Asad (the lions’ shrine), Ein al-Dabe’ (the hyenas’ spring), Deir al-Hijleh (the bird’s spring), Jibt al-Dhib (the wolf’s corner), Ein Fara (the mouse’s spring), Jabal Haidar (The lion’s Mountain), Oyoun al-Baqar (the cows’ spring), Deir al-Dubban (the flies Monastery), Karad al-Baqar (the cow’s herder), al-Samakiya (the fish village), Wadi abu al-Hayat (the snakes valley), Ein Gedi (the ibex’s valley), Abu Zreiq (The jay’s village), and Hijr al-Ghoul (the ghoul’s cave); Abu Suhweileh, Khillet al-Tha’lab (the fox’s quarter). The lived, the intimate and the feared gave names to the place and space around it. Each of these names carry within it a story, a being – a cave or a valley that is also a refuge. Each name is a ghost haunting and disrupting the past, present and future of the Israeli occupation.

3.

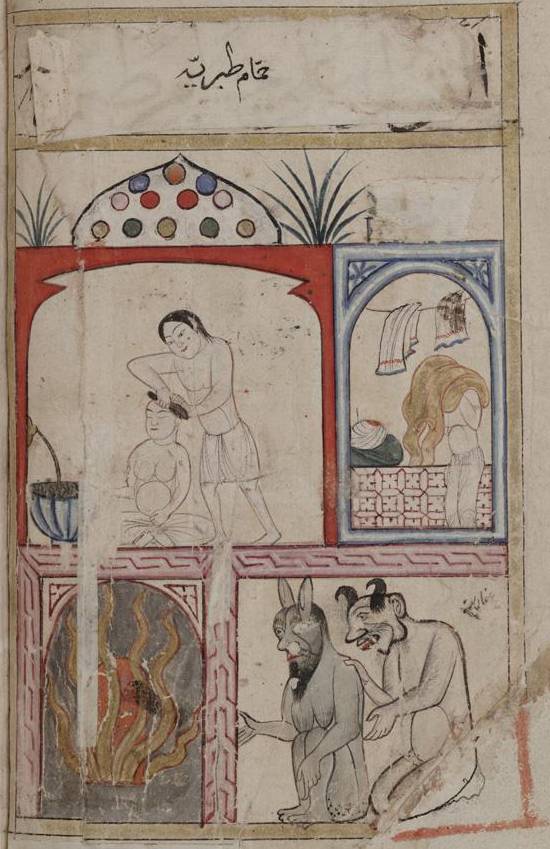

Baths of Tiberius. Men bathing while demons tend the furnace. From the Book of Wonders by al-Isfahani (late 14th century)

In Tawfiq Canaan’s essay on Haunted Springs and Water Demons in Palestine (1922), he explains that ahl al-ard [Djinn] come from the interior of the earth and therefore “we meet them generally in places which have a direct connection with the lower region: trees whose roots go down into the interior of the earth; cracks; caves; springs and wells which have a direct or indirect connection with the above named original abode of the demons.” In the case of hot springs, particularly the ones near Tiberias, he tells us that “King Solomon ordered these djinn to perform this piece of work [heating the water] in order to give the inhabitants of Palestine a natural hot bath”. This is also confirmed by al-Masudi in The Meadows of Gold (947 AD) and al-Isfahani (illustration below). The djinn put to task were deaf and blind, and never learnt of Solomon’s death - and so they still heat the spring waters today until they run dry. How does a myth hold down a space?

Sing for them to see is a brilliant body of work composed by singer and composer Maya Al Khaldi in which she interprets and renders audible a history of foraging, of movement and care, protection and singing around/to a spring. In the village of Ras Karkar, nearby a spring and maqam [shrine] named after al-Nabi Ayoub [prophet Job], Al Khaldi sought and learnt songs from the Maqam-keeper; a woman who committed herself to the protection of the shrine and spring, which were once a source for communal washing, drinking and healing before military outposts and settlements occupied the surrounding hills. The songs we hear hold a plea for the waters to overflow and heal; they also summon the strength and patience of al-Nabi Ayoub to persist.

Pom Poko (1994) by Studio Ghibli. Tanuki in a fight.

Where the striped hyenas are is not only a place in the imagination or in the past. Where the striped hyenas are is also a possibility for what the future could bring. It’s where they lie, waiting for their turn to return from their exile. Where the hyenas are is also where the ghouls and the djinn are, behind seven mountains, dreaming and chasing their world into being again.

Like a Studio Ghibli world, what if all fantastical creatures were to rise up against the dispossessions and alienations from the lands that sustain them, to which they belong? Like the raccoon dogs in Pom Poko (1994), they could shape-shift, infiltrate, and start a ballsy revolution to interrupt settlement expansion and the destruction of their worlds. They could interrupt the function of checkpoints, walls, spotlights, watchtowers, and construction projects, driven not by the just and rational but by the relational and producing another realm of endless possibility. How can the fantastical embody the political? And will it allow us to dream a dream that is more solid than reality?

4.

12 years ago, I walked with my dad, mum, sister, and grandpa Jalal in Saidoun صيدون. Sidi Jalal was probably 20 years old when the village was raided and destroyed in 1948. The only house left standing is the house of his uncle Salim al-Biss, by tinet al-Sheikh Hassan [a fig tree under which both my grandpas learned to read in the kuttab6]. Before visiting Saidoun with him, my grandpa - a carpenter - recreated a mock of our village from memory. This “sculpture” and tales told choreographed my walking in a place I belong to but had never been in. Those very brief and infrequent visits to the remains of displaced villages, the passing on of memories, and the creation of new living ones mark the stubbornness of returning and leaving traces over and over again. These moments and the dreams dreamt within and through them are one part of a resistance to the temporary permanence of the occupation.

Jalal Mohammed Thiab Albess picking figs in Saidoun in 2011. Photo by Saba’ Nader Jalal Albess

But what else is our walking?

Walking to breathe. Walking to recross. Walking into exile. Walking to re-stitch. Walking shoulder to shoulder. Walking through a terraced hill. Using our feet to find holes in walls. Following the scent of sage and thyme. Walking to return. Walking to leave traces. Walking on time. Walking on layers of dirt holding the remains of those who walked before. Walking in the opposite direction of a white concrete backdrop. Walking is a set of transformations set in motion; with each step, we unearth what has been forgotten.

Where the striped hyenas are is not only a place in the imagination or in the past. Where the striped hyenas are is also a possibility for what the future could bring. It’s where they lie, waiting for their turn to return from their exile. Where the hyenas are is also where the ghouls and the djinn are, behind seven mountains, dreaming and chasing their world into being again.