Mumbai-based Jyoti Nisha is an academic, writer, screenwriter and filmmaker with a focus on cinema, gaze, caste, gender and media, and she has ten years of experience in print, radio and television. Her article ‘Indian Cinema and the Bahujan Spectatorship’ in the Economic and Political Weekly is credited with conceptualizing a theory that opposes the popular culture’s casteist male gaze and stereotypical representation of the marginalized, earlier called untouchables, on the silver screen.

Who gets love in popular culture? I have been thinking about this question for a decade now. Soon after its release last August, I went to watch a film that surprised me in ways I had never imagined. Pa Ranjith’s latest film, Natchathiram Nagargiradhu, which translates to ‘a star shoots across,’ seems to have answered all our questions about the idea of contemporary love. Trust me, there is an interpretation for everyone - inter-caste, inter-faith, queer love, inclusivity, sexuality, woman as a category, genderless casteless love.

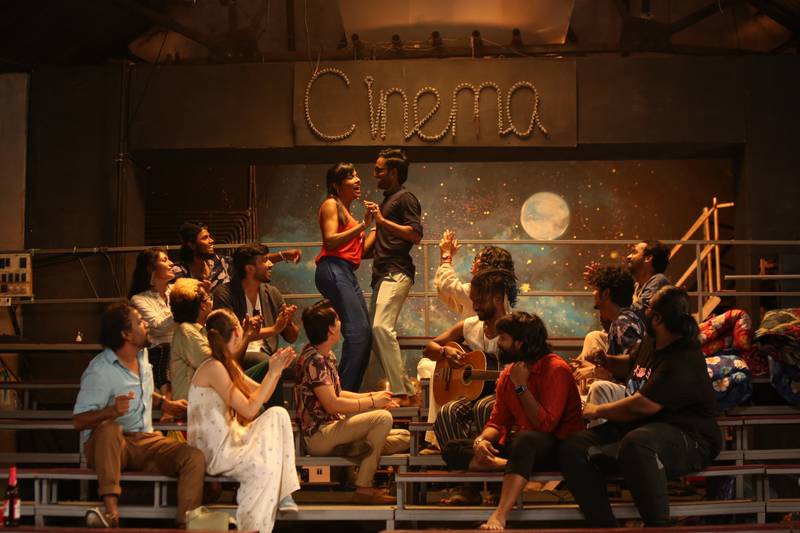

The way Ranjith sees the urban Indian society is refreshing, authentic and political. He embodies the power of a conversation into one of the finest scenes in Indian cinema. Subeer (Regin Rose), a theater director, wants to make a play on love. And, there begins a conversation leading to various interpretations, heated discussions, and face-offs unmasking people’s politics and standpoints. Subeer has opened a can of worms. Set in Auroville, Pondicherry, the theater backdrop serves as the microcosm of modern Indian society and the idea of community and allyship. Medellin, a french woman, argues that love is a universal feeling; Sylvia, a transwoman (Sherin Celine Mathew), discusses the idea of exclusion and acceptance of love from her partner, Joel, despite her trans identity. Tragically, she committed suicide in real life. Praveen and Diana are for genderless, casteless love. Arjun’s idea of love is a filmy stereotype filled with scheming and deceit. Diana thinks love is the freedom to find oneself. When Inyan expresses that love is not romantic but painful, Yashwanth interjects, ‘but there are also people who kill their children in the name of love.’ He talks about honour killing. Rene speaks of structural inequalities, caste conditioning and branding of a community when it comes to love. Love is certainly political. Another member hits out at the ideology, ‘Once you kill the ideology behind such killings, there shouldn’t be any problem. Love is ideological.’

The film’s progression of dialogues and politics is a constant transgression from what has been told in stories of love in popular culture. It is authentic for the very reason that it represents people from the margins in power. A casteless genderless love. Love that is inclusive. These stories are stories of people’s experience and their transgression from the binary lens. It is no coincidence that Pa Ranjith cast Sherin Celine Mathew, a transwoman, to play Sylvia’s role in the film. His cinema is inclusive and Ambedkarite, raising existential questions as a person from a community and as an artist, proving that cinema is a cultural, ideological state apparatus and representation matters.

The tone of the film is set from the start. The movie opens with a top-angle shot of Rene (Dushara Vijayan) and Inyan (Kalidas Jayaram) lying exhausted in bed; Nina Simone’s ‘Feeling Good’ is playing in the background, revealing to you they have just made love. Rene pauses the music and asks Iniyan, ‘Should we get married?’ Sleepy and tired, Inyan answers, ‘Let’s.’ She wonders about the significance of marriage. ‘But, what’s love if it sustains only because of an institution of marriage, not otherwise? That won’t do with me. I won’t.’ Inyan seconds Rene mindlessly and irritably, ‘Let’s not then!’ Lying next to him, feeling his skin, Rene starts singing an Ilaiyaraaja song that irritates Inyan further, and he asks her to stop singing. He is sleepy, but Rene isn’t. He shuts her mouth, she continues singing. He loses his cool and throws a fit. Rene takes offence, ‘What ya? You can listen to Nina Simone, but you can’t listen to Ilaiyaraja?’ Inyan answers, ‘I don’t want to listen to any song. I want to sleep.’ Rene provokes him further and continues singing. Inyan yells, ‘Tamil!!’ An attack on Rene because her name is Tamizh! Rene corrects him by explaining the correct pronunciation of her name, “It’s not Tamil. It’s Tamizh!” Call me Rene. It is I who decides how I should be addressed.’ She continues singing. Irritated, Inyan takes another dig at Ilayaraja, ‘Birds of the same feather flock together.’ That’s a trait of a casteist person. Rene is aware they are ideologically opposite, but she plays cool, somewhat funny, defiantly and calmly. She says, ‘You know your problem is not Ilaiyaraaja. It’s me.’

Throughout watching this film, I wondered why Ranjith chose to give Rene a song and why she was laughing in this first scene. During this scene, Rene’s sarcasm and laughter are a defense mechanism to ward off the casteist gaze at her social identity and being. I do the same, dance, laugh, or indulge in both. As a person from the community, I can say for sure that we know the experience and have the awareness to identify how and when someone looks at us with a casteist gaze. It is irrational, blasphemous and small-minded. So, Rene’s defiance and laughter hit home in a personal way. An assertive Rene asks Inyan, ‘What is your problem? Be open about it. I will help you.’ She first tries love, then gestures for a hug. She hugs Iniyan, but he pushes her away. Rene observes Iniyan’s caste blindness with, ‘It’s all in your head, throw that away.’ It is abundantly evident that men have felt threatened whenever women have taken center stage. But, when a woman from a marginalized background claims her space, most upper caste men and women feel attacked and victimized and complain of reverse casteism just like Iniyan does, ‘I want to. But it’s eating my head.’ Rene says. ‘Am I?’ Inyan, ‘No, I am my problem. If my words and deeds are wrong, then I am the problem, right?’ He feels suffocated. Rene smiles, ‘If something is wrong, it is. Set it right. Let’s both do it. Rene is talking about allyship with her lover here. She is clear. But Iniyan again gets personal, ‘You should correct yourself first.’ ‘I would definitely correct myself if I were wrong.’ Inyan gapes, ‘Oh! Really? It’s my bad then’. Rene gets irritated, ‘What is your problem? Just ask me straight.’ It is evident Inyan is threatened by Rene’s assertion.

At that moment, I could see myself in Rene. I was stunned that Ranjith could see this woman, giving us her character. And how beautifully Dushara embodies Rene’s spirit. A woman’s assured sense of self can only come from consciously practising the praxis of anti-caste politics and assertion. Women from marginalized backgrounds are acutely aware of their fights. They understand the ideology behind it and know that the fight is ideological. I think artists create a temperament for social change in society, and Ranjith’s films and work have done that so consistently that the Indian film industry cannot deny his brilliance and the cultural movement he has propelled. Rene’s character is a point of reference in popular space now.

Inyan and Rene’s personalities establish their ideological standpoints, yet they are attracted to each other like water and fire. Iniyan disses the maestro, while for Rene, Ilaiyaraaja symbolizes empowerment despite his caste identity, but Inyan can’t fathom the comparison between Simone and Illaiyaraaja. The fight goes out of hand, and Iniyan makes another casteist comment, ‘All said and done, your nature won’t change!’ ‘The nature of my caste, you mean?’ shoots back Rene. ‘Just now, when you were licking me, my caste nature didn’t matter to you.’ Inyan loses his cool. He pushes her and yells, ‘Die bitch!!’ Rene falls. But this heroine just doesn’t deal with the fall. She is one of those who will hit you back if her integrity is attacked, and Rene does just that. Next, you see Rene walking in the middle of the night on the road holding a photo of Buddha and her phone case, a pride flag representative of the LGBTQ community’s politics of inclusivity. They have broken up.

Throughout watching this film, I wondered why Ranjith chose to give Rene a song and why she was laughing in this first scene. During this scene, Rene’s sarcasm and laughter are a defense mechanism to ward off the casteist gaze at her social identity and being. I do the same, dance, laugh, or indulge in both. As a person from the community, I can say for sure that we know the experience and have the awareness to identify how and when someone looks at us with a casteist gaze. It is irrational, blasphemous and small-minded.

Ranjith has reversed the gaze of popular culture’s submissive good girl image of a heroine. Here the connotations are assigned from an ideological standpoint and amply symbolic. Played brilliantly by Dushara Vijayan, Rene is not that one-dimensional woman running around men or trees on the screen. She is a self-assured woman. She is critical, intimidating and hot. Here is your young angry Ambedkarite heroine, who thinks, is empathetic, compassionate, knows her politics and acts on it too. This is the bold heroine of Ranjith, and I just loved that about her. During one of the scenes, Arjun questions, as most liberals do, rarely aware that there is an entirely different imagination of the nation which is separate from that of Right or Left ideology: “ you a communist?” “I’m an Ambedkarite,” says Rene and digs a plate of beef fry. And that’s a win for us as a community. Rene, the girl with blue hair and a septum ring, is an agent of Ambedkarite ideology, the first assertive political heroine whose character and the role will go down in the history of Indian cinema. She is truly symbolic.

Rene reminded me of Puyal, aka Stormy, Ranjith’s previous heroine in his film Kaala, the ultra-angry political activist played by Anjali Patil. During a scene of communal violence at Dharavi, Stormy was the woman who had the balls to hit back at the police who had stripped her down in public. Rene is a calmer version. She is an actress and model who is seen reading Ambedkar’s Buddha and his Dhamma and shows remarkable empathy and scientific temperament. She is conscious to the point where when Arjun crosses his boundaries with her, and she thoughtfully gives him a chance to correct himself. “Political correctness will not come in a day,” she says. “He should face each of us. Face his mistakes. If he goes away, he will never learn. I think this is the best space and place for him to correct himself. He must stay.” she says.

Ranjith gives Rene exceptional agency. She is the woman of today beyond the stereotypical idea of woman seen as a site of body, sexuality, morality, perversion, etc. This woman is ideological. She is critical of popular culture’s stereotypes, branding and the structural hierarchies’ persistent casteist attack on her community. In Natchathiram Nagargiradhu, caste has been explored at an ideological level. It is not physical this time. If it is, it is through his ideological nemesis - Inyan, the fair, good-looking dominant caste guy who loves Nina Simone but looks down on Ilayaraja. Inyan can afford to look at the beauty of tea plantations, but Rene questions the slavery and exploitation of three generations of marginalised communities in making Red Tea. There is the second type, Arjun, an aspiring actor who comes from a dominant caste and finds it hard to fit in. His parents want him to get married to Roshini, played by Vinsu Rachel Sam. But, Arjun being a misogynist, casteist, homophobic and transphobic cis heterosexuals male, is conditioned to see in binaries and seen cracking uncomfortable jokes around Sylvia, a transwoman, Diana and Praveen - a gay couple who are all part of the theater group. His toxicity is repeatedly checked to shocked faces when he is constantly questioned, ‘where did you study / learn that?’ The third is the ultra-violent, fascist protector of culture, Master Cat embodying the violent nature of caste ideology. All three display variations of violence, Inyan at an intellectual level, Arjun when he makes transphobic, homophobic remarks at Sylvia’s party, and how the Master Cat attempts to destroy their play itself. Does the play happen? It does but at the cost of violence. The whole system is involved. The police are involved. That’s your repressive state apparatus, which represses anyone who asserts or questions their politics. The assertion is countered by violence because the system understands politics too well.

Ranjith illustrates caste-based killings as honour killings through his characters’ testimony within their play - Wild Cat / Domestic Cat. Ranjith has blurred the lines between fiction, non-fiction and theater as he makes his case of honour killing in Natchathiram Nagargiradhu. He uses puppetry to make a point.

During one of the theatre’s rehearsals in the film, women tell stories of how their lovers (men) were attacked and murdered for crossing the threshold of endogamy (marrying within caste). How can loving someone be wrong, asks one of the women. The song En Janme, the lyrics penned by Uma Devi - ‘If I told you the story of our murderers. Like the bright lightning over the hill, your lamps would burn for hours. If I told you stories of our deaths, nights would run into days. Your lamps would lose oil,’ may haunt you as it brings to the surface the systemic pain, angst and suffering behind the caste (honour) killing. As the lyrics run through the screen, ‘A woman’s rage would kill so you make me Gods. My dear people… we see various shots of women’s deities and their bodies spread all over, exemplifying the hypocrisy of the same Hindu ideology which puts women on a pedestal to be worshipped but deny and mutilates their agency and bodies for real. The women’s oral histories point out how the caste system demands the murders and sacrifice of a Bahujan body and how untouchability and pollution are intertwined with that murder.

Ranjith has posed questions to Indian society and the intellectual class of India in the way he has explored his story and the issue of honour killings. Identity has been explored from various perspectives. After Rene has allowed Arjun a place for transformation, Arjun questions Rene one day, ‘Who are you, Rene?? Are you the one that you show to the world, or are you the one hiding behind??’

Rene recalls how hauntingly caste has followed her entire life. There were several instances. When she had to step down in sludge in her village for upper caste men, when she was abused with caste slurs for taking a bath in a public pond and how her honour and dignity were torn to pieces when she had to run back to her home semi-naked, another time, when she was threatened for picking tamarind fruit, another when her peers and teachers mocked her choice food of beef, another when she was looked down upon because her father played Parai in public, another when she was harassed for holding a scholarship and the final nail in the coffin was Inyan, her liberal upper caste lover and artist who attacked her because of her social identity and because he couldn’t keep up with a woman who thinks and owns her identity. “Yes, I am a shattered glass, but I have recreated myself with arrogance, clarity and assurance. I’d like to think of myself as a much stronger and braver person. Yes!! This is my social identity.” There is certainly nothing more potent than the agency of a broken woman who has repeatedly built herself, and Rene is that for me. All the stereotyping of the community, especially Dalit women, have been burnt down to ashes in the assertion of Rene’s social identity in this scene. Pain does create a space for transformation, unlearning and reconstruction. You saw that in Rene. You see that in Inyan and Arjun.

What’s interesting about this film is that women have been chosen to annihilate and perpetuate the caste hierarchy. Back home, when Arjun visits his grandmother and tells his mother that he is in love with Rene. A question about the girl’s caste immediately pops up. Arjun, whose heart has shifted recently, loses his cool. His mother insists she cannot talk to his father unless she knows the girl’s caste. The next moment, all hell breaks loose as her mother enters the kitchen teary-eyed. Concerned, her daughters ask her the cause of her suffering, and she says, ‘Your brother is going to get us killed. He is in love with a Scheduled Caste girl.’ One of Arjun’s sisters says, ‘we should get them married if they love each other. Love is normal.’ Her mother and her other sister diss her. They also force Arjun to agree to marry Roshni from their caste. Her mother justifies and takes pride in the caste killing of their aunt by their great great grandfather. She even fakes killing herself to blackmail her son. Once Arjun is pinned to the wishes of his mother. She asks for nimbu-mirchi to take the curse away, a ritual to ward off negative energy. In this case, Rene.

The sister, who is pro-love, signifies that she wants to break caste, but the mother and other women want to contain it. It is self-explanatory that women are the biggest victims of caste and the biggest vehicles to perpetuate caste because caste pride and honour reside in the body of the women. There can also be those who, like Rene, are done with the pretence and want to annihilate caste. So many of us want to. This has to be one of the boldest and equally blasphemous scenes on screen, which derives real laughter. The dying grandmother opposes - ‘I don’t want my grandson’s life to be ruined as mine was.’ She, too, is the victim of patriarchy and Brahmanical ideology. Ambedkar said women are the gateways of the caste system. Their autonomy over their sexuality will annihilate caste and untouchability.

The song Rangarattinam with rap lyrics, ‘We are the brightest, greatest, wisest, righteous future, we are the movers, we are the shakers’ is an ideology and the lived experience dancing in your face, owning them all, loving them all. This is Ranjith’s best film, for sure. There are several other reasons to watch this film. It is relevant. Ranjith is in tune with the times, considering what is happening at this time in the history of Indian cinema when the state is going through so much. He is relevant, and how! Representation matters. It is everything you question, aspire to ask and achieve in terms of representation. Therefore, this film is a movement of inclusivity and a transgression in the visual language of cinema. Producing creates scientific questions. What you see, you can talk about it. You can reference knowledge. Therefore, producing such a kind of cinema also creates a pedagogy of understanding the impact of image-making in cinema. Ranjith has given us glimpses of the Ambedkarite community and an assertive heroine.

There are several other reasons to watch this film. It is relevant. Ranjith is in tune with the times, considering what is happening at this time in the history of Indian cinema when the state is going through so much. He is relevant, and how! Representation matters. It is everything you question, aspire to ask and achieve in terms of representation. Therefore, this film is a movement of inclusivity and a transgression in the visual language of cinema.

Pa Ranjith continuously reverses the language of cinema in his aesthetics, gaze, and culture that is formed by shared histories, collective experience, solidarity and a movement of assertion. His images are that of a painter. He plays with colours and themes. He explores his nemesis in white, as was seen in Kaala. Haridev Abhyankar is obsessed with purity, and that’s how Master Cat, the protector of culture in this film, is. The colour scheme and this visual language are also a departure for Ranjith. Reminded me of Wong Kar Wai’s visual style. The way the editor Selva RK transitions Rene and Iniyan’s section seamlessly (on Kadhalar) made me wonder if the scene was written in the screenplay as is or if it was edited like that. Music director Tenma’s score reminds of Rahman’s Roja in some odd ways giving an ample feeling of peace, cosmos, disco and passion in Kadhalar. I loved the production design, costume and lighting in this film. Especially the mural of Buddha and the way he illuminates as the door opens. It is symbolic. When Inyan comes to see Rene at the start of their relationship, Rene is playing with an elephant which is also synonymous with Bahujan politics in the North, as the Elephant is the symbol of the Bahujan Samaj Party. Being a North Indian, Jenny Dolly’s great subtitling helped me understand the film without losing its political nuance. Language is political too. The spectatorship of this film is an existential, visceral, spiritual and intellectual experience. I haven’t seen anything like that before, but I did imagine.

Natchathiram Nagargiradhu is now streaming on Netflix.