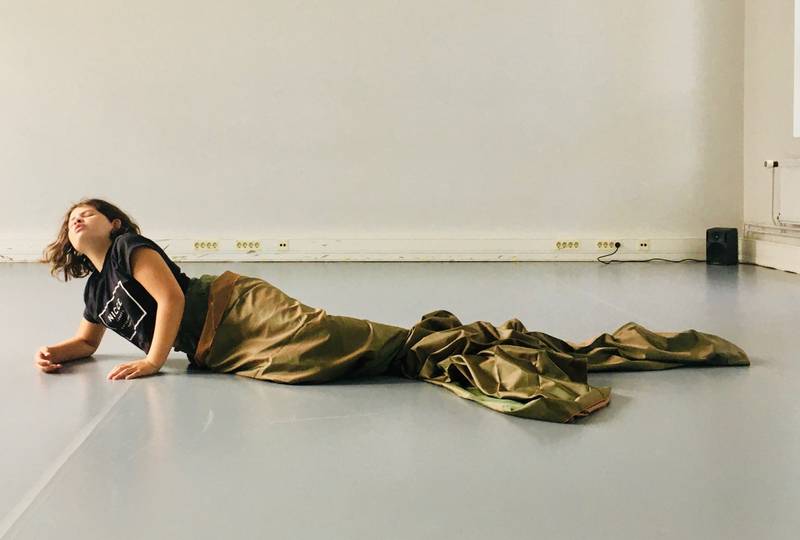

Volta Rajakangas-Moussaoui, 2021, work in progress for Venus. Photo: Janina Rajakangas.

María Villa (Bogotá 1977) is a facilitator, curator, and researcher based in Helsinki. She works in the crossroads of feminist epistemologies, radical pedagogy, relational art, and embodied practices. She is a multidisciplinary practitioner interested in entanglements of care in complex contemporary forms of interdependence and unlearning binary mindsets. Her work explores varied media, from voice, movement, and performance to experimental writing and cartographic practices. Runner, baker, mother.

Detail of Birth of Venus, by Sandro Botticelli (c. 1484–1486). Tempera on canvas. 172.5 cm × 278.9 cm. Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Venus, the Roman goddess, in her “pearl perfection,” as the Uffizi proudly present this icon of Western art painted by Sandro Botticelli around 1480 in Italy, is emerging from the ocean in a clam shell.

She’s just been born out of the foam—thanks to the severed genitals of Uranus thrown into the sea’s womb— yet Venus is already coming of age.

An adult but a virgin, wringing the seawater from her hair, modestly covering herself. She is the fairness of her flesh, an epitome of innocence and frailty, ripe for the visual pleasure of the beholder. But her story seems to stop there. Being born is enough; no ageing, learning, or acting in the world is envisioned. Being that perfect, naive body and being displayed and loved is already an accomplishment.

1480.

In Latin, venus designates love, desire, charm, adoration (as in venerable); but the root of the word (wenos) is also present in venom, as in love-drink, magic philter; and we hear its echo in venereal disease. Her Greek counterpart, Aphrodite (aphrós (ἀφρός), literally “sea-foam”), would endlessly renew her virginity, her purity, in the same sea water. According to her many devotees through European history, she was said to aid fertility but she was as well, of course, the patron goddess of prostitutes. In early Rome, old sources say, girls coming-of-age would offer their toys to Venus as a rite of passage, or as a token for prenuptial good auspice. Boy’s rites into manhood, in contrast, entailed becoming citizens and starting military training.

1480.

And what does that have to do with us, with youth, love, and desire in 2023?

Nothing, and everything

The Performance

In this essay, I tap into Janina Rajakangas’ surreal rendition of the myth of the Birth of Venus presented last November in Baltic Circle (Helsinki) and XS Festival (Turku), a work that rewrites the story of the Roman goddess in an unsettling, warm, and fierce light. This piece, emerging from an artistic collaboration with a group of teenagers (Natalia Foster, Mea Holappa, Seela Merenluoma, and Volta Rajakangas-Moussaoui) over seven months, restages Venus in a dramaturgy that is as polyphonic aesthetically as it is touching, irreverent, and courageous.

Picture a small wood and stone house surrounded by snow by the beach in Lauttasaari: Villa Salin, owned by Naisiasialiitto Unioni, a Finnish feminist association founded in 1892. Inside, crowded in the eteinen, the thirty-people audience removes their coats and shoes to enter a dimly lit living room, walls covered top to bottom with baroque paintings, mirrors, and draperies. A bare Persian carpet lays at the centre. Those sensitive to loud noises are wisely advised to take earplugs. We sit on the assorted Luis XVI furniture lined up on the edges like we have come to visit our grandma for some glögi,… Loud noises? Before we are all settled, four barefooted girls in disparate happy colorful clothes come kneel at the center, light a few candles, and start quietly and slowly reciting, looking into each other’s eyes: Honest, friendly, kind, gentle,… careful, receptive, quiet, humble. The tone and demeanor envelop us slowly, almost in a whisper, a sweet and intimate plea, even flirtatious. And yet, repeated over and over, it gradually feels different, stronger… they take us in a vertiginous progression into discomfort, fear, frustration, and outrage: gentle!, careful!, receptive!, quiet!, humble!

The performance has the grammar of a spell. These four girls sweep us—adults, peers, parents, and friends—into a journey through rhythm, strikingly beautiful singing, talking, banging, moving, humming, posing for the selfie, and unscripted dancing from the gut. The audience is infused with a touch that feels like burning again, where we ache for affect or endure hormonal upheavals. They take us under their skin.

Janina Rajakangas & working group: Venus. 2022. Baltic Circle. Photo: © Tani Simberg, courtesy of the choreographer.

But they take us as well under the patriarchal gaze that seeps through their every interaction: in the city; on the treacherous public/private street of social media and its terrifying dark alleys; in posting themselves for likes; in sexting; in the stereotypes they half desire and half just tolerate, ironize, or plainly suffer. Their voices and movements made vivid how they are constantly judged or misinterpreted as they try to navigate and find a safe space within all this, how they fight back, break into anxiety and depression, or eventually fail to cope with the pressure and explode. And how they are judged for that too: angry, dopey, dramatic, problematic, adolescent, intimidating, trouble-making, delusional,…like everyone but no one! Crazy, loud, unstable!

In a conversation we had days after the show, Janina tells me how this work first started: with herself, a puzzled mother trying to unpack the way her daughter’s life, identity, and sense of self-worth were swiftly changing and being shaped through digital interactions.

When my daughter was around 10 years old, I started noticing her behavior online and how she was presenting herself, and I thought it was very classical male gaze material—how she was dressing and what sort of positions she was taking, what angle she was using. I was quite shocked to realize that a young girl already knows how she should present herself to be accepted. And then I began thinking about writing a piece about it and doing it with her to deal with this issue, to start looking into it together. We did a couple of residencies, just the two of us. It was also the time of COVID. I couldn’t really work with anyone, so I worked with her.

Janina had been working on another project, Teen (2017), that investigated with adolescents several questions cutting across her recent pieces, for which non-professional dancers are essential. Questions about intimacy, connection, and movement: Which bodies get to dance? What does dance look like and feel like for them? How may those movements bring in everyday life to the stage and may expand that same life in unpredictable ways? How can dance take on a transformative course where a different relationship with bodies, personal and those of others, is explored?

However, the dialogue this time quickly touched upon a very complicated matter: the erotization of young girls, abuse, harassment, the desperate need for coordinates and boundaries, and the loud ideas about beauty and desirability that aggressively frame today’s mainstream gendered norms through the attention economy of social media. It eventually landed as well on young girls’ innocence, their desire, and their rage; their performed physical perfection an imperative that is shame-sculpted into their identity, and patriarchal views on seduction shape it all. Venus, 1480.

In our conversation, Janina stressed how physicality and touch were so central in a teenager’s life, not just for the need for boundaries but also, paradoxically, an important affective dimension of existence (and for her own mother-daughter relationship) oscillating between needing distance and proximity:

It all came from loving someone at this age. I guess in a sort of crisis, or a moment of change, a child needs to be in your arms, or they need more. There are, of course, moments when they take distance, but there are also others when they need caressing or like they need to know that they’re okay because the change has been so huge in those years, and because everything that has to do with touch has meaning at that age, they are thinking through it. They are beings in becoming. Touch is now valued in a different way. Or you need to think through who can touch you and where they can touch you, whereas a child is free of that.

And how does one work with all that?

The project expanded into a quartet when Janina invited three other girls to join this exploration. The collaborative process involved dialogue on the many other aspects of teenage life and experimenting with ways to embody, rewrite, or explore them via voice, rhythm, and movement. She took notes, worked on the lyrics and the text for the piece, and proposed songs based on these conversations. Then she would suggest the version, either physically or in text, for the group to reflect together on how it worked, what felt right, and how to develop it.

She recalls how easy it was to navigate the topic, partly because the performers were eager to open it up, share, and discuss all the ramifications of it. They needed a space to articulate these feelings and experiences, in particular their online lives, from which all of them had actively taken conscious time off—the older they were, the more they understood its troubling content.

This took place just after the pandemic had swept through our social and communal existence. It is no secret that teenagers were disproportionately affected by it precisely because of how central interaction is in this delicate and tumultuous passage between childhood and adulthood. They were locked up in there, thirsty and deprived of resonance and affection as we all were, but in a much more vulnerable position than children and adults are to the messy manipulations of online existence. Isolated, in search of answers to who they are or wish to be, they may also become easy prey to toxic ideas and predatory behavior. And the social world around them was coming to an unprecedented halt that would alter the grammar of (adult) interaction in ways no one could foresee.

Could there be a way to rewrite or reclaim that myth of love and desire? And what would that look like? Janina explains that they wanted to find a way to present the issue without following the predictable directions and by redefining the girl’s relationship with the goddess.

I feel that I am a bit too old for the male gaze, because the perfect goddess is in her twenties, maybe just about the beginning of her thirties. And my daughter was too young, of course. We were both on either side of it. None of us could match it, but I felt we were still trying; we’re both still trying to somehow fit that role. […] So one of my interests was to remake the goddess. How can you then, in a live situation where people are watching you, rewrite it? […] I wanted to look into this goddess of love and try to challenge her. What else could it be beyond what is usually presented? It was then that someone called the performance a spell: a spell for it to be otherwise.

We talked about witches and making magic. And so, in order to make a change, what would be the form? So then we played that there was the circle of witches who were trying to become humble and honest at the start, like “good girls” ought to be.

First, they started looking into images from paintings of Venus and how she had been pictured, and then somehow went into a different iconography, one often used online among teenagers where self-harming emerges, and they make videos for TikTok about feeling bad or hurting themselves with The Sound of Silence as a soundtrack. On one side, this was horrific, but on the other, it highlighted how online presence was allowing teens to talk about mental health openly. The image of the depressed girl, sinking deep, surfaces also in Venus as being contained, surrounded by others.

Janina Rajakangas & working group: Venus. 2022. Baltic Circle. Photo: © Tani Simberg, courtesy of the choreographer.

And later, when we have been following a troubling sequence where the refusal of these girls to play the whole game is clear… Suddenly the goddess appears. Venus shows up as all the ramifications of its objectified flesh are floating in the air. The goddess is re-staged remarkably, her icon appropriated by these bodies without forcing the analogy or making it trite, and every detail that is put into this one image as the girls sing grounds it further in a goddess of love that feels as familiar, approachable, and real, as it is strong and challenging.

The questions behind it

As a researcher and curator, I am fascinated by the way Janina’s work thinks through different forms of embodiment that are part of movement, how she explores practices of movement and living in these widely different bodies of ours in the everyday, and how that is staged in her choreographies. In my view, an important part of this work is precisely how affects and troubling questions are mobilized by the dancers and with the audience. And how we might imagine other ways to live in these bodies beyond biopolitical constraints and binary norms. When I ask her about this dimension of the practice and its liberating potential, she explains:

I find that the space we have for physical expression in everyday life in Finnish society is very limited. How are we allowed to embody our feelings or states? We are mainly allowed to sit and walk. And I find that there is such huge potential. For example, in Over your fucking body, I addressed the fact that most of us are fucking, but we are talking about embodiment and dancing as if we were not fucking. So there’s this secret life of everyone, which is surely not a secret because we have the porn industry and a lot of products around sex, but still, when going to a dance show, we always ask “Why do they do these weird things?”. And then we go home, and we have sex with our partner or partners, and we are very close to what we’ve just seen onstage, but we don’t combine this. We can’t see that this is already in me.

All these things are already in us and are the vocabulary for this emotional world … my work is very much about making a movement practice out of that. I guess that’s where it this practice of freedom takes place. […] it is a way of communicating available to anyone. And then, of course, a very very important part is that it is in peace. It’s a movement practice that is not violent.

In this space for diversity in embodiment, her works open up avenues for the fluidity of beings, allowing bodies to support each other and expanding the possible modes of being and feeling in the dance space. In this search, a process of discovery that dives into our emotional makeup, Janina investigates how age is embodied (or masculinity, intimacy, anxiety, and power), bringing a fresh and often uncanny playfulness to how we navigate gestures and social codes. Her work is a multilayered movement research (Mårten 2018) in constant shifting as much a mise-en-scène that engages directly with the audience in subtle and irreverent ways.

Janina Rajakangas & working group: Venus. 2022. Baltic Circle. Photo: © Tani Simberg, courtesy of the choreographer

Depending on the topic at hand, she might join the performance or, as in Venus, step out of the stage altogether and give other bodies full voice. Unlike many performances catering for the inclusivity topic in the art grant system—which deal today with marginalized bodies in gestures that border on tokenism or merely play around with stereotypes—Janina’s work feels both real and nuanced because it is grounded in the experiences, stories, and relationships of those same bodies that confront us, instead of aiming for performative illustrations.

I try to start with: who does this issue belong to? In this case, I wanted to talk about this erotization of young girls, which was touching me as a person and bothering me, and then make a piece about it. I could never imagine professional dancers making this piece with me. I can’t imagine that there would be anyone else besides the actual subjects. It was very clear that they need to be teenagers themselves who perform and embody the subject because it’s their issue. And then, in the process of making, I start to think about what needs to be or could be embodied. For example, with them, I thought about what sort of physical freedom of movement is possible. We talked about “living room dances” when nobody is watching. Or at a high school party, if there are performances, what would never be in there? So this is how we made the animals, like the dinosaur and the pig, and other things that were there. A girl could never impersonate an animal in public. It would be too embarrassing, or it wouldn’t be accepted.

There is something raw, incredibly affective, personal, beyond language, ambivalent yet deeply empowering, that keeps pulsing in works like Meadows (2021) in the effort of deconstructing and queering male embodiment or approaching the dancing bodies of elders in 24 Dances (2021), and now with this quartet of Venus—girls discovering a path to resist objectification and sexualization of their bodies and the manipulation of their identities. Through the dramaturgy coming together in these pieces, there is something that defies any representation tricks, taking the work to a different level altogether. Something that brings on a load of kinesthetic empathy that makes it quite hard to subtract yourself and look at the work as a detached outsider.

Towards the end of our conversation, we touched upon the small space where the piece was presented, Villa Salin, with the group of senior feminists that welcomed the process into their home, in particular discussing sound and voice in Venus:

Sound has this thing that it goes quite straight into people. Sound either if it’s loud or if it’s really beautifully sung. One pivotal point for me was screaming, because I keep hearing feminists talk about how women are not allowed to use their voice. Loud girls are not accepted. Even in the school world, a loud girl is always a really bad thing. It’s worse than a loud boy. […] And then in the Finnish parliament, as we were making this piece, there was also one male minister who said that these five women who are in charge of the government at the moment had been screaming about something. This idea that women scream like men never scream.

So I also wanted just to let them scream because they scream in such a way! … I could really see that the teenagers are having a feminist fight in their daily lives. It’s the same old issues of women’s rights. That is why I wanted to go somewhere where women have been fighting for their rights and to give them that space. […]

It’s funny. First, we went there, and we were a bit fearful that we were going to be too wild for the space. But then, actually, everyone, even these older ladies who look after the house, was very touched and very happy that we were there. We even broke something from one of the lamps, and they were just like, It’s okay. It’s life.

Janina Rajakangas and working group: Venus. 2022. Baltic Circle. Photo: Tani Simberg, courtesy of the choreographer