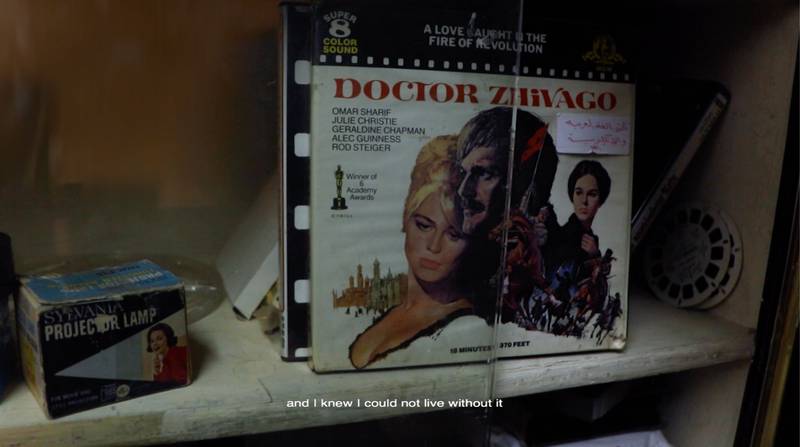

Still from Cineholic, Film by Sherko Abbas & Shirwan Fatih, 2021

Natasha Marie Llorens is an independent curator and writer based in Stockholm, where she teaches art theory at the Royal Institute of Art. Llorens is a regular contributor to Artforum and e-flux Criticism. Her writing has also recently appeared in ArtPapers, Art Margins, and frieze, as well as in exhibition catalogs for Djamel Tatah and Ulrike Rosenbach, among others. She was awarded the Andy Warhol Arts Writers grant for short-form art criticism in 2022. Llorens holds a Ph.D. from Columbia University (2021) and an MA from the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College (2011).

Abdulqadir, an impeccably dressed man in his sixties, carefully winds a length of film back into its canister. The bright white cotton of his shirt flashes beneath the cuff of a well-fitted dark wool suit jacket, and a heavy, deep blue silk necktie is knotted carefully at his throat. Frameless contemporary eyeglasses perch on the bridge of his nose as he handles the machinery of this underground cinema club, of which he is the founder and proprietor.

A voiceover speaking in Arabic has already introduced the context: Sherko Abbas and Shirwan Fatih’s 25-minute video Cineholic (2021) takes place in present-day Iraq, a country deeply marked by the 2003 US invasion. Despite the impression left by Abdulqadir’s fastidious care for material history and calm competence, Cineholic (2021) unfolds in the aftermath of the severe damage inflicted on the film industry by war. The big public cinemas have either closed or been transformed into shops or storage spaces. A close-up shot shows celluloid flickering through well-oiled machinery. The image goes black for a moment, and a voice off-screen asks if the power has been cut. It has, but a second voice reassuringly confirms that a generator will kick in shortly. There is a rupture in the visual field, but people have also developed measures to compensate for the absence of light.

His hands moving carefully to operate one of the many film projectors in the basement, Abdulqadir explains that cinema disappeared from Kirkuk and the rest of Iraq because of the terrorist attacks that began in 2004, a year after the United States’ military invaded the country. As he speaks about the breakdown in public space, the shot changes to show Abdulqadir’s face. Speaking in Kurdish, his words are sparse, and there is restrained emotion in his eyes. “That is why cinema owners shut their businesses, and that was the end of it.”

Still from Cineholic, Film by Sherko Abbas & Shirwan Fatih, 2021

As the camera pans around the small basement room, it lingers on a small image of Hitler. This startling fascist apparition is set in a yellowing plastic frame and placed on a shelf alongside other keepsakes, such as the roughly cut caricature of a wooden film clapper. Sherko Abbas observed other portraits of the war criminal in several places where Iraqi cinephiles gather. “When I inquired as to why there were so many pictures of Hitler,” Abbas writes, “Abdulqadir explained that film reels featuring Hitler are relatively inexpensive. This is why they are commonly found among collectors of Iraqi cinema. Abdulqadir even showed me a particular picture of Hitler that he obtained along with a film and several posters at a flea market in Kirkuk.”1 Abdulqadir’s response implies that, in Iraq, the material fact that cinema exists is crucial regardless of what is pictured, even at the political extremes of what has been captured on celluloid. For Abbas, the sequence “convey[s] the idea that we are discussing the consequences of war and how the people in the film witness cinema disappearing from the public as a result of war.”2

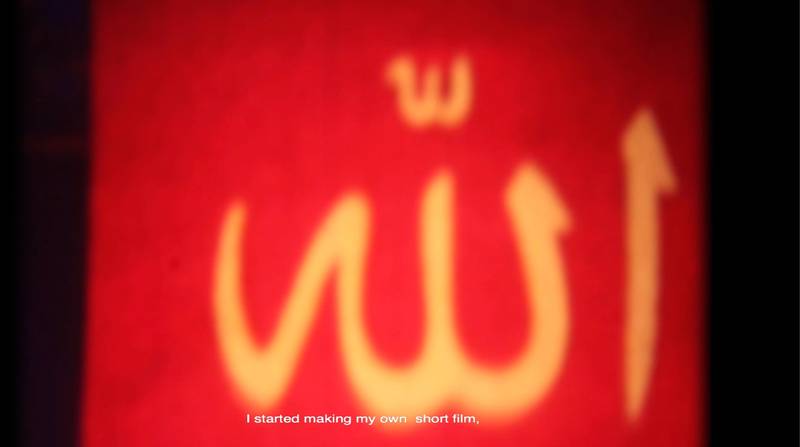

Still from Cineholic, Film by Sherko Abbas & Shirwan Fatih, 2021

A brief historical sketch to contextualize the public space in question: Cineholic is set in Kirkuk, a small city in the north of the country where the Iraqi oil industry was founded. From 1851 through the end of the First World War, the city fell under Ottoman rule. In 1918, just under a decade, it was ruled by the British Mandate before the Treaty of Angora granted it to the Kingdom of Iraq in 1926. Oil was discovered at the city limits in 1927, and what had been a small, diverse, but still predominantly Turkomen settlement began to transform. Attracted by a booming petroleum-fueled economy, Arab and Kurdish people emigrated and established their own neighborhoods, laying claim to the city. In the second half of the 20th century, a series of violent power struggles shaped Kirkuk: the Turkomen massacre by pro-communist largely Kurdish forces in 1959, a sustained and violent campaign of “Arabization” waged by Saddam Hussein’s government (1979-2003), and the reciprocal “Kurdification” initiative begun after the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. Post-war, Kirkuk continues to be a flashpoint for ethnically-defined conflicts.

This tumultuous history is the milieu in which people in Cineholic form an attachment to cinema and to the moving image. Abbas sees their investment in the medium in line with what French philosopher Michel Foucault might describe as an archaeological approach to the representation of war; cinema as a way to make the repressed histories of knowledge about war in Iraq sensible once again. Abbas writes:

I believe that our (young Iraqis’) interest in war films, including mine, has a psychological explanation. We are from the generation that experienced the Iran-Iraq War.3 During that time, there was only one TV channel owned by the Iraqi authority that aired war films, documentaries about WW2, songs related to war, and even cartoons that linked to the propaganda of the war by the Saddam regime.4

Cineholic, in other words, is a film about cinema in a context in which the role of the medium has been to mediate between the Iraqi population and an almost constant state of conflict—first during the Iran-Iraq war, then the First Gulf War, then the Second, and finally the past twenty years of simmering civil unrest in the wake of the regime’s forced dismantlement by the US.

Cinema has also long been tied directly to statecraft in Iraq, though to date there is no authoritative published history about the medium. The first film was projected in Iraq in 1909, and for the first decades, it consisted primarily of silent films imported from the United States for the British stationed there during its mandate.5 In 1948, King Faisal II established the first Iraqi production company, Baghdad Studio, backed by French and British investors. But the initiative was short-lived and critically unsuccessful, as it was largely seen as producing Orientalizing commercial films or propaganda for the monarchy.6 Nevertheless, some alternative initiatives flourished in the margins, such as the World of Arts (Dunyat Alfann) studio, which produced Fitna wa Hassan (1955), directed by Haidar Al-Omar. The film depicts a thwarted love story in the Iraqi countryside that got some international distribution at the time.

When King Faisel II’s government was overthrown in 1958 in a left-wing military coup, the new regime set up the General Organization for Cinema and Theatre to facilitate the production of its own propaganda films. In 1968, a Baathist led-coup invested heavily in the construction of film theaters, especially in the 1970s when oil revenues were nationalized and income spiked during two oil crises in 1973 and 1979. Nevertheless, the Baathists did not significantly favor independent or critical films. Instead, they financed documentary films like Al Maghishi Project (1969), a portrait of the government’s irrigation campaigns in the Iraqi countryside.

The people [in the film] believe that if the enemy were victorious—and the catastrophe or the death of cinema that the film depicts were to be achieved—no one would be able to remember the past. They know that this enemy has not ceased to be triumphant, yet they do not surrender. Watching a film for them is fighting.

Still from Cineholic, Film by Sherko Abbas & Shirwan Fatih, 2021

As Cineholic shows so vividly, however, in addition to the lack of places to see films, Iraqis suffered from unreliable access to the materials and infrastructure necessary to make them. Before the First Gulf War in 1991, for example, there were 275 cinemas in Iraq, but the international embargo imposed after that war banned the importation of both film-making equipment and celluloid from entering the country. Iraqis were stuck with what they had already imported or what could be smuggled in through VHS-tape and other emerging technologies. The long struggle to control national narrativization by controlling access to the stuff of film explains the visual attention Abbas and Ferhat pay to Abdulqadir’s care of objects and celluloid. This struggle also contextualizes Cineholic’s slow burning political claim, articulated concisely by Iraqi film critic Peshraw Mohamed:

The people [in the film] believe that if the enemy were victorious—and the catastrophe or the death of cinema that the film depicts were to be achieved—no one would be able to remember the past. They know that this enemy has not ceased to be triumphant, yet they do not surrender. Watching a film for them is fighting.7

To relinquish film for men like Abdulqadir is to give in to a sustained attempt by successive regimes to control history, along with the willful erasure of memory that diverges from whichever ideological line is dominant.

In the work’s second passage, an unremarkable sedan makes its way slowly through Kirkuk’s streets. The camera is positioned inside the car, its lens directed out towards the city; permission to film outside is tricky in such a heavily contested public space. A man on the side of the road signals to those driving to stop and then gets into a passenger seat in the back. He is at ease, dressed as unremarkably as the car, perhaps in his late fifties. Hussien Abdul Wahid begins to tell a story about the first film he made, entitled Gold Medal, which was finished in 1980, the year war broke out between Iran and Iraq. He describes sending the film to Germany to be developed, as there were no facilities for positive film development in the country.

Cineholic cuts to excerpts of Abdul Wahid’s first film as he tells its story. A teenage boy doing pushups on a home weight bench; two boys fighting (theatrically) in the arid landscape framed by sandstone, shirtless and wiry in the way teenage boys are. In tone and some narrative elements, the footage reminds me of Hito Steyerl’s video work November (2004), which includes video shot in the 1980s in Germany of Steyerl’s youth—the same to which Germany Abdul Wahid sent the rushes of Gold Medal for development.

On one level, November is a portrait of Kurdish independence activist Andrea Wolf’s struggle to keep the persecution of the Turkish Kurds in the German news. On a more structural level, the work questions the way images of revolution move (or fail to move) through Western European media landscapes. In both November and Gold Metal, I have the impression of watching Hollywood choreographies of struggle repurposed for a different conflict, one in which the political roles are reversed—much like in Tewfik Fares’ 1969 Algerian classic film, Les hors-la-loi (The Outlaws).

Still from Cineholic, Film by Sherko Abbas & Shirwan Fatih, 2021

Still from Cineholic, Film by Sherko Abbas & Shirwan Fatih, 2021

Cutting back to the present, the unremarkable car with the small group of friends drives into a building that used to be the Hamra, a big cinema in the center of Kirkuk transformed into a car park for imported vehicles. It has been stripped of any sign of its previous role as a cavernous home for flickering images. Abdul Wahid, the would-be filmmaker, stands in the vaulting but bare concrete interior and lists the films he saw here: Godzilla, Superman, Bollywood films, and Arabic movies in the 1970s. Not a trace is left of their imaginative worlds. It is precisely this kind of apparently totalizing erasure that Abdul Wahid and Abdulqadir, along with Abbas, Ferhat, and their generation, are fighting against. In an echo of Abdulqadir’s tone from the beginning of the video, Cineholic depicts the absence of any historical sign flatly. In his analysis of the Hamra’s repurposing, Peshraw Mohamed is less sanguine:

The film also traces the catastrophes of neoliberalism, which the USA lent to Iraq under the name of progress. There was a collective cinema auditorium in the 1980s, which today has been turned into a garage for imported cars, which is a sign of neoliberalism and a free-market economy. Where the USA wanted to show the people of Iraq the appearance of a new chain of progress, the film shows one single catastrophe, which unceasingly piles rubble on top of rubble and hurls it before our eyes.8

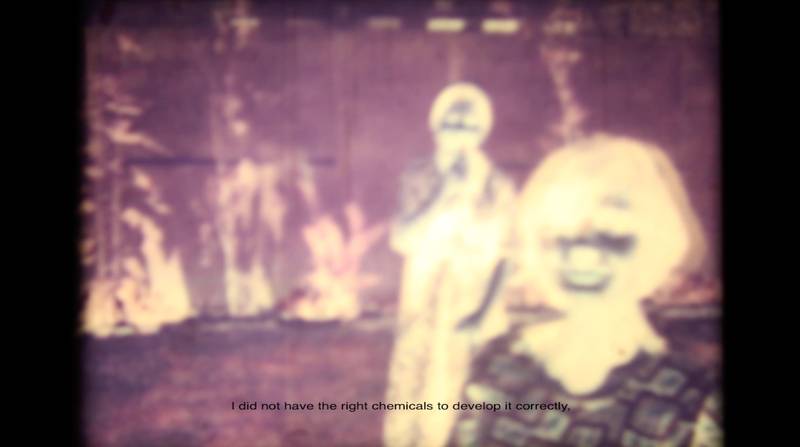

Back on the road, Abdul Wahid speaks about his second film, started in 1980. He posted it to Germany to have the film developed, but it was returned to him within 3 to 4 days. The policeman explained that it is now illegal to send things out of Iraq on account of the Iran-Iraq war. Access had been cut. Determined, Abdul Wahid made the film with what he had on hand, which was to develop negative film. The film print came out as a negative image, with people rendered as apparitions against a dense background. Footage again runs beneath Abdul Wahid’s narrative, showing phantom figures moving through the public space.

Still from Cineholic, Film by Sherko Abbas & Shirwan Fatih, 2021

Still from Cineholic, Film by Sherko Abbas & Shirwan Fatih, 2021

This second film remained in negative form until 2006, when Abdul Wahid acquired technology that allowed him to shoot the video in negative and then make a positive print—he was finally able to process the ghosts captured two and a half decades before and return them to a kind of liveness. The positive print, when scenes from it are cut into Cineholic, is quite different from Gold Metal. Though the quality is degraded, it is possible to see women, children, and men with 1980s haircuts in loose, flared clothing. This is a record of middle-class people living their lives before the worst destruction from the subsequent wars descended, still flush from a successful revolutionary coup and with the promise of oil revenue still active for civil society. These images could have been shot in Athens or Marseille in the 1980s. This kind of footage makes it possible to imagine a family trip to Hamra to see Superman.

Films support the important work of fantasizing, but they also support the much less spectacular but equally important work of registering everyday life, facilitating long-term solidarity, and manifesting subtle instances of individual resistance.

In the carpark, a pickup truck moves slowly across gravel spread out on the building’s bare concrete foundation, where carpet used to be. Abdul Wahid drags a couch across the ground to bring it parallel to a back wall, on which he improvises a projection screen. A square of light splashes across the wall, which has deep red gashes in it from ancient paint that no one has bothered to fully remove. Alone with his small portable projector, Abdul Wahid screens his second film.

Cineholic is a powerful testament to the multivalent political function of film, which both represents alternative (past and future) imaginations of the social realm and provides an important material vector for existing forms of resistance. Films support the important work of fantasizing, but they also support the much less spectacular but equally important work of registering everyday life, facilitating long-term solidarity, and manifesting subtle instances of individual resistance.

Abbas and Ferhat frame this penultimate shot from a distance, taking in both the illumination of this man’s filmic memory and the light from an exit, the same exit the pickup truck has just used to go back out into Kirkuk’s erstwhile public space. The viewer is given a double portrait of the carpark/theater, which exists between its former life and its current one, the small, newly-positive image next to the passageway for imported cars. A gorgeous shot of Abdul Wahid’s hand resting on the back of the projector as an image flickers out of focus in the background. When it sharpens, a woman, unveiled, smiles unquestioningly into the camera. This is a private moment, but it demonstrates how one man can insist on the possibility of another configuration of the social in Kirkuk. Cineholic reminds the viewer not to underestimate the value of this quiet aesthetico-political resistance.

Cineholic is available to stream on Shasha Movies.