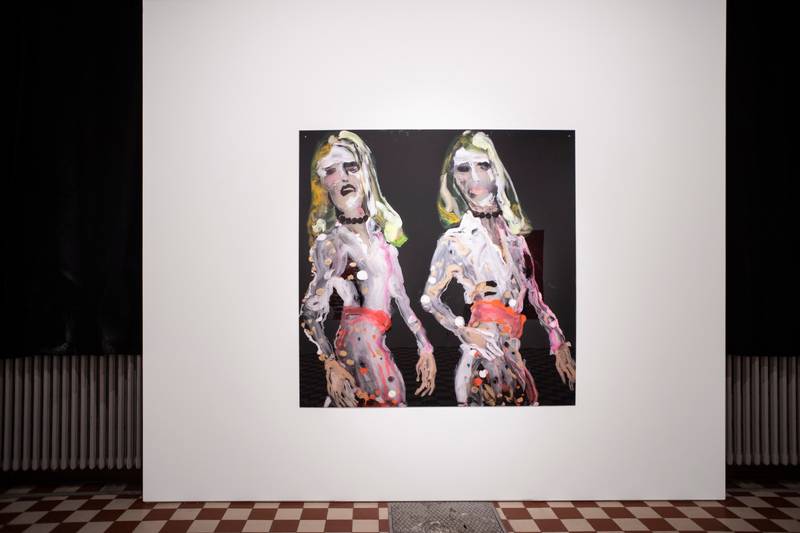

A Couple in Black (detail), 2021, oil on plexiglass 170x 130 cm

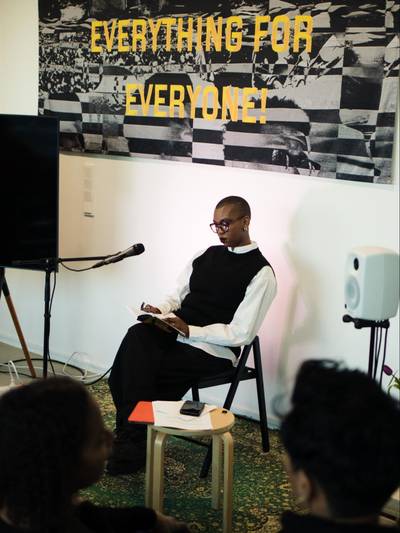

Saara Mahbouba (b. 1993, San Jose CA) is a visual artist, artistic researcher, and writer currently based in Helsinki. Her research interests are primarily in the intersection of identity and labor. She draws on a mix of critical theory and pop culture, using the forms of popular media to make her research interests more widely accessible. She works with cultural programming and organizing in multiple forms, both independently and as a part of varying arts and community organizations. Saara holds a B.A. from NYU and an M.A. from Aalto University.

This interview reflects a surreal but rewarding afternoon I spent getting to know Kirsti Tuokko and discussing her recent exhibition OH DEAR, on view at Galleria Huuto in February 2021. To meet in person we had to negotiate with COVID, braving the early March grey and chill to sit outside, huddling over coffee cups, socially distanced on some benches in Fredan Tori. Perhaps because of the strangeness of our meeting, the conversation quickly broke through any formalities. Our discussion moved through different iterations of Kirsti’s lifetime as a painter and person, navigating gender roles, prescribed pathways, uncertainty, pleasure, and guilt. Perhaps, more than anything, it was a conversation about the complex ways we find our paths and influences, and how we choose to communicate ourselves to the world.

Minkki Nurmi, Portrait of Kirsti Tuokko, 2021, felt-tip pens and digital drawing

SAARA: Congrats on your exhibition, OH DEAR! It seems to have been received very well. I spoke to a few people – to get their reactions to the work – and one person, another artist, described you as somewhat of an icon on the Helsinki art scene. As someone who’s been established on the scene for some time, with a memorable persona, yet still has kind of an outsider presence. Do you connect with that description at all?

KIRSTI: As an icon? I really didn’t think about myself like that. I’m an artist who started late, like 25 years ago, when I was around 50 years old. I was an art teacher, but I knew all the time that I should do something myself too. I was often with my students looking at exhibitions as part of our program and I had the feeling that it’s a shame that I don’t make my own work. I took a loan to leave the school for three months and then I got a studio, and these were the main points – the time and getting myself a place to work. Then in 1995, I had my first exhibition in Tampere, and Tampere City bought one of my paintings. I thought maybe I am not at all on the wrong path, I should go on.

Would you say there was some kind of changing point in your life that led to this decision?

I think one changing point, it wasn’t the reason, but it allowed me to get some more time for painting, was when I got my divorce. I didn’t have a man to take care of in the house anymore. My son was at his father’s every other weekend, so two weekends in a month, I could stay in my studio. I’m happy about that, that my children are on their own in different ways, so I have my time for me.

It’s funny, as a child when I was thinking about my life, I imagined my future as having a family life. Already then, I thought, why does it have to be so narrow? Why can’t I imagine something else? But getting married was quite as obligatory as school exams, you get rid of school and then relatively quickly get married. I was envious already at the time that for the boys it was so much wider, the field of the future and what the future might be. For women and girls, it was family.

You mention in your exhibition text that a lot of your inspiration comes from fashion magazines and passersby in the city, what were you looking for from these inspirations? Were you drawn to people that seemed to be living lifestyles that existed outside of these narrow confines?

I have a memory for all my clothes. I remember what I was wearing during my school age and the clothes that the neighbors had. Somehow it’s built in me and when I walk down the street, I enjoy it. It’s not like in the early fifties when everyone was using the same uniform. Different presences now bring a kind of communication and joy – street performance – where you can see in a visual way people communicating with their innovations in how they dress, and I like it. I like cities and Helsinki is the best city in Finland for me. I simply like the buildings and I like the sea, I like the people and the streets, and I like the way that you are not so known. I don’t consciously collect clothes or how people wear their clothes, or what is coming up in style. I’m like a big whale that siphons in all these tiny, tiny invisible creatures. It just comes. I’m interested, definitely interested, in how people present themselves or present the person they think they are.

Alex, 2021, oil on plexiglass, 170 x 170 cm. The image is reflected in the painting A Couple in Black, 2021

That’s a very vivid way of describing it. When you’re painting, do you work mainly from memory, drawing on these inspirations you’ve siphoned in from the street?

No, no, I buy fashion magazines. Some 20 years ago, when I started with this fashion thing, I thought how nice, now I can submit these magazine receipts for my taxes, now that they are my working materials.

Sometimes it’s really the small things that give us life.

Buying these fine, glossy, thick magazines, it’s a part of me. In a way, the things that I think about, people, and their relations, nature, and the climate, it somehow captures that all. The nautinto – maybe pleasure? – but it’s deeper, it’s more. Pleasure is a bit thin in describing the feeling. There’s a deep satisfaction and joy that you can get from dressing and clothes, but at the same time, they are always accompanied by a big guilt because of climate change and useless consumption. In that sense, painting somehow helps me, when you can’t so clearly divide these things. Though pleasure should maybe be more ethical and moral, I take pleasure from this guilty thing.

Is painting something of a way to bypass consumerism and guilt? Instead of having to buy the clothes and be a part of that culture, you can put them on the plexi in paint on your own terms?

Yeah, that brings me enjoyment and satisfaction. It has in fact been so concrete in my life that when I’ve seen something in the shop that I definitely want to have, I’ve painted it.

I also wonder – because we were talking earlier about how gender norms and roles have impacted your life – how the widening understandings of gender that we are starting to see reach even fashion magazines have impacted your work.

I think that many of the characters that I have been painting can be genderless. In my magazines, there have been young men posing in women’s clothes and it has been addressed to women. The clothes I personally wear – quite a lot are genderless. That genderless thing is in there, you can’t tell for sure if my characters are men and women.

There’s an interesting contradiction in your paintings. On one hand, it can be considered very traditional portraiture, with a figure captured against a blank background, with a lot of importance placed on their dress and the way they present themselves. But at the same time, it seems like your figures are not necessarily individuals, they seem somewhat faceless and abstracted, more of a collective, standing in for a moment in time or culture.

That might be true, anyhow for these years that I have been painting my fashions, people have been telling me that I am very ajassakiinni – with the times or relevant – but for me, with the painting, it is also very important that the character of the paint has to be there. I just enjoy the paint as a material. When I do my paintings on the backside of the plexi, the paint can have some autonomy. It can take its own ways if it wants to run. So we somehow work together.

You also mention in your exhibition text, that each painting or character has a little bit of yourself in it too.

That’s important for me. Of course, painting is fine when you do it without handprints – like paintings of icons – where there is no human touch anymore, like a ready-born thing. But I like this character that paint has the ability to bring. It reflects somehow, also, my attempt to be a person. My characters stand as if they are looking at themselves. They have put a lot of effort into getting themselves and the outfit ready, and then they are looking in the last mirror at home, thinking how did it work? And maybe it’s okay, but they are not quite sure now if it reflects what one wants to be.

Different presences now bring a kind of communication and joy – street performance – where you can see in a visual way people communicating with their innovations in how they dress, and I like it.

That tension seems to be present in your paintings – these moments when we bridge between our inner worlds and the public world – and in a way, it’s a very loaded moment. There might be joy and excitement, but there’s also a little bit of fear there too, or perhaps uncertainty would be more accurate when we confront how the public perceives us or how we perceive ourselves through the public eye.

Yes, you are putting it in a very fine way. Sure, as it happens in real life, many outfits look quite fine in the home mirror, but then when you are there with all the other outfits and the other people, you see that it maybe wasn’t fine.

Does that relate also to your painting and exhibiting process too? Is it a stressful transition?

It is a stressful process, very stressful. It’s just like with the dressing up. In my studio, I am there in front of that last mirror in the entryway. I’m doing my things, I’m getting happy with my creations, what I have invented, and so on. But when I start to get out, to the party, to the outer world with my creations, then the moment of truth is coming and I have to be strong enough to face it.

I was just so unsure about my exhibition. When I hung it I felt it was okay. But then I started to feel, is it good enough? I went back to the studio and did some small paintings there to reassure myself and then I felt I had to go back to Huuto to see how it looks. Has it changed? But I got some nice comments from artist friends and from those friends in the art world whose opinions I really trust, and they kindly paid some visits to my studio and somehow backed me up. Now I have been having some two weeks period where I think that I’m okay and why have I been making myself so small and unsure, but I know it will also pass. It’s a definite thing that you can’t be sure permanently, there is always this thing, going up and down.

Oh Dear 3 (detail), 2020, oil on plexiglass, 170 x 170 cm

I just enjoy the paint as a material. When I do my paintings on the backside of the plexi, the paint can have some autonomy. It can take its own ways if it wants to run. So we somehow work together.

That final panic is hard to avoid but it’s always frustrating when you get back to those moments of confidence and wonder, why can’t I just remember this later? But I think in a way if you are always floating on this plane of constant confidence, and sureness, you can’t go very deep, letting doubts have room can be important. What is your working process like? Is doubt a part of it?

I think that’s what I learned to think during these 25 years that I’ve been doing this. That uncertainty is a necessary tool because it pushes you to new angles of what you want to reach. My work is in a way that I can’t plan it. My thinking goes hand in hand with handicraft and material work. I think most afterwards, after combining material thinking. It might be some color combination or contrast of light or dark, that might be the start of what I am looking for in the magazine, or it might be quite a thin, small thing. But when I have it ready on the other side, the painting tells me what I have been thinking. I don’t believe in inspiration. I go to the studio all the time and I might sit there and read my phone if I don’t do anything, but I need to get there. Mostly even if you think nothing will happen there, you might just catch the most essential small idea that you start to develop.

Some paintings are standing there a long time and get some layers on the front side, that’s the only way I can change them or maybe make them better. But mostly they come a la prima, in one thing, and sometimes I have to let them dry, there’s so much liquid on one side I can’t finish. But I am busy washing the paintings too. Sometimes I’m not ready to accept a painting, then I wash it away. Sometimes later, after a year, I see photographs of them on my phone, and I don’t understand why I needed to erase them.

That was mentioned to me and it’s something I find quite interesting because I feel that I tend to hoard my work, to have a visible track record that something has actually happened. Is washing away an avoidance of clutter for you? Does it clear up mental space?

I’m good at throwing away, I’m very good at it. At my age, I don’t have furniture. I have my bed, I have my round table and my chairs. I don’t have an armchair. I even have very little dishware. With that, I’m really good. I think about if I should buy something into my small home, and I’m able to think that then you lose the space. I can think like that, but with my clothes, I can’t.

And I’m really happy when I get the plexiglass clean. It’s not a simple process. It takes several days to get it spotless because the tiniest little needlepoint of paint needs to be washed away. You need a dark background to see the light spots and light to see the dark. It’s kind of a long-time meditative process.

Petra and Paula in Local Disco, 2020, oil on plexiglass, 170 x 170 cm

This fear of dying before I tried this thing, that was my thing, was maybe the main point why I asked for a loan from the bank to start painting.

In a way, it could be considered a form of performance art?

I have been told that I should make videos of the washing. Now after the exhibition, I have washed two paintings away. I try to keep exhibited paintings for some time, but then when I think about climate change and nature, the only modern feature in my work is this washing away. Otherwise, I just make objects. Then, I also think it’s kind of nice, to think of it as a concept that I have a long line of characters that have visited in my studio, and by washing away, they have gone into the immaterial form, but they have been there. They are somehow present. They have different personalities, but it grows with time. I see more about the characters with time, and somehow this brings me back to my school age. I was inventing stories quite a lot so I go back to that in a way.

Kind of like a lifecycle, people are here temporarily and then leave again? But as you said these characters also represent parts of you. In a way, I think we all live so many versions of ourselves, all these mini lifetimes in one life. This feels like a way to give each of those space, and kind of come to terms with those versions of the self. If that gets cut out, you lose this connection to the self too, maybe.

Of course, people always see their lives as a kind of continuous story, it’s always so easy to tell it afterward that it has been this, but no I think it really has been more like that. That’s very true. When I started these paintings, around 50 years old, I had a period during that time that I was finding terrible diseases and ran to doctors and thought that I would die. This fear of dying before I tried this thing, that was my thing, was maybe the main point why I asked for a loan from the bank to start painting.

So it really kind of came from within you, this need to do this.

Yes, I felt that it will be a real shame if I never get to do that, but I guess there are many people who never come to their real field. When I was an art teacher at a school for 33 years, I tried at first to bring all the students to a bit more conceptual level but then I realized, there’s no point at all. They need to get the enjoyment of the thing at the same time; it has to be concrete and immediate. I’m relatively happy because I think that this is what I can do. As I said about my students, they need to get the enjoyment. And I get the pleasure and the enjoyment in my studio. You can’t give up the joy you get in the studio, that’s the main joy.

Alex, 2021, oil on plexiglass, 170 x 170 cm

Installation view, OH DEAR, Galleria Huuto, Helsinki

Installation view, OH DEAR, Galleria Huuto, Helsinki

Installation view, OH DEAR, Galleria Huuto, Helsinki