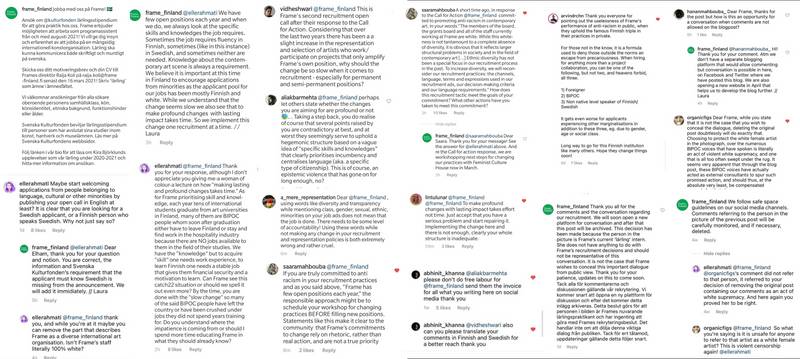

The screenshot is a combined image of screenshots shared with the author by some of the participating individuals in the comments section. The purpose of sharing the screenshots is to put forward several pertinent questions that remain unanswered. The screenshots are being shared with the permission of each individual contributor. This permission was not sought from Frame as it is a public institution and not a private individual.

Farbod Fakharzadeh (b.1986) is an Iranian artist, curator and storyteller based in Helsinki, Finland. In 2018 he received a Master’s degree in Visual Culture, Curating and Contemporary Art from Aalto University. He is interested in using the magical, the comical and the absurd to create his version of social critique and he often works with history, archives and recycled material as tools for storytelling, re-imagining the possible and dreaming about parallel realities. He is also a co-founder of Taidekirppis, an archive project (currently on hold) in Helsinki.

“Not everything that is faced can be changed; but nothing can be changed until it is faced”1

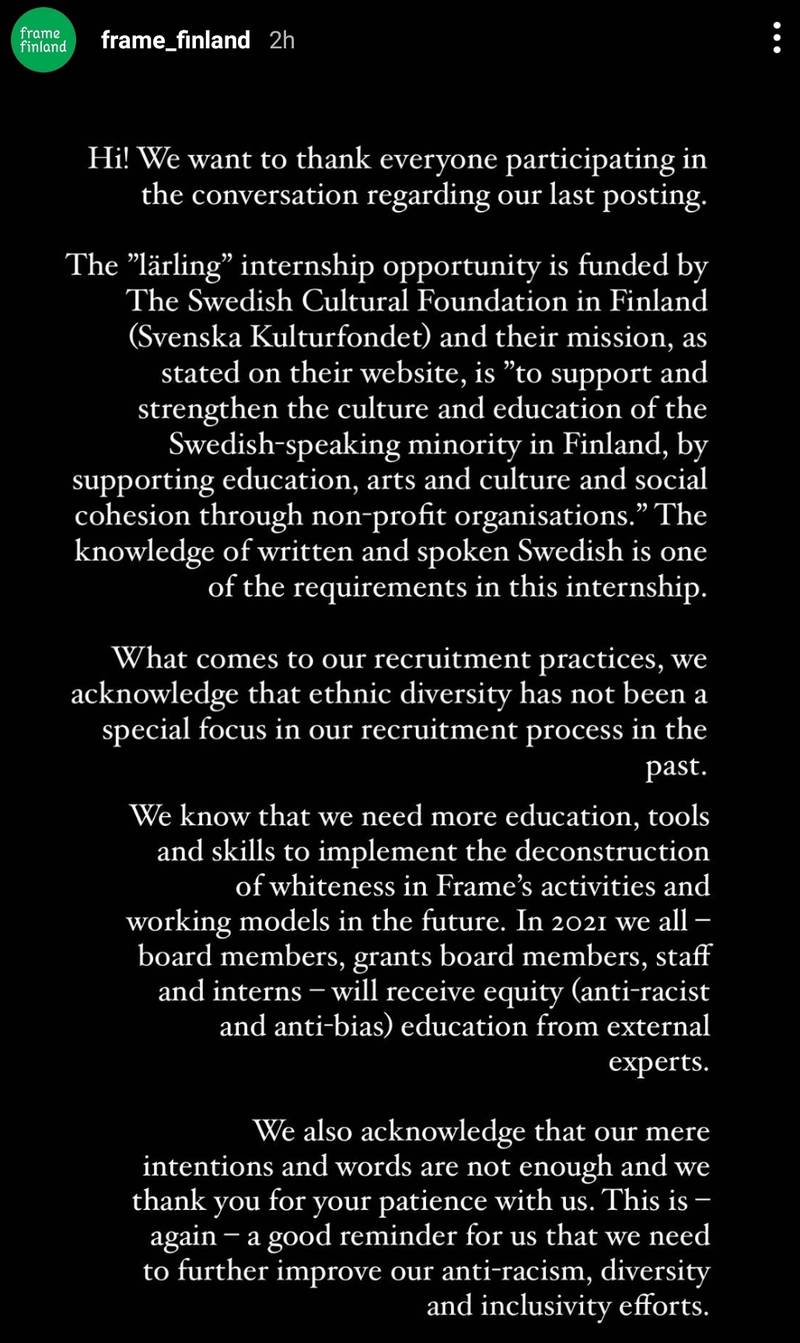

It all began with a now-deleted post on Frame’s Instagram account when the open call for an internship position supported by the Swedish Cultural Foundation was published only in Swedish. What started with a few questions regarding the nature of the open call soon grew into a heated debate and triggered an opportunity for the exposure of several arguments and points of view in the form of a much-needed conversation regarding Frame’s recruitment and engagement policies.

Contrary to their statement of gratitude towards the contributors to the aforementioned conversation, in practice, Frame’s leadership disregarded the time and effort spent by all those contributors when they decided to delete the post together with all the comments. They instead published a text2 by Frame’s director in response to the situation.

Notes:

- The following text is not a detailed response to the problematics and wrongful assumptions that were made by Frame in light of last month’s events. Doing so necessitates detailed conversations involving both sides which does not seem feasible nor welcomed at the moment.

- This open letter is an intimate, personal yet collective reflection and reminder that hopes to commemorate aspects of what went down, and serve as a document of the conversations that happened and points that were made in light of Frame’s decision to replace them with their own monologic narrative.

- My goal with this letter is not to villainize Frame as an institution nor it is to convey that these issues are only present in that particular setting.

- “Frame”, in the following text, does not represent a single individual. It’s rather a personified institutional structure that the writer has chosen to confide in.

Dear Frame,

You may not remember me but I remember you!

These days I think a lot about how naive I was just a few years ago. Back in 2013-2014 when I moved to Finland to study, I was so eager to explore and experience this new learning and working environment. During our first year at school, there were some sessions in which we met a few people and got acquainted with the practices of their institutions including you, HIAP and some of your other friends. That was coincidently a time in which you all had new directors. As a newcomer, I was told in our orientation class at university that Finland has a very low rate of corruption and that decision makings are always kept transparent. I remember during those meetings the thing I was most impressed with was the directorship terms. As an outsider, the fact that there was always the open possibility for people to apply for these positions and how they’re planned as fixed-term placements which change every three or five years was really impressive. I’m not planning to get into the problematics of the open call system or democracy here but at the time I thought this system stops institutions from falling into a state of stagnation. A state that I was all too familiar with. At the time, I thought there would be a possibility for actual change in direction and modes of practice by the new people coming in and assuming these main roles.

As I said, I was very naive. I still thought Western academics really mean what they say in their books. Later I realized that they’ll do the exact opposite if their position of power is threatened. I don’t claim to know the inside dynamics of the decision making in institutions like you but at some point, I got a bit confused. The truth is, those three or five years passed and still most of the institutional directors that started their term with my entry to Finland are still holding those same positions! I wonder, is it because they’re so amazingly talented at what they do that even considering the fact that someone else may also be able to do this job would be unthinkable?!

There was a point made in the text published on the Frame blog which referred to the employment protection laws in a welfare state like Finland and how you ended up with almost entirely permanent staff. Have I missed something here or did you at some point stop sharing information with us? Surely there are reasons for this that the people who are making these decisions see that I don’t, and it has led to this situation. But from the outside, where we stand and have stood for what feels like an eternity, it seems like at some point a “democratic” electoral term-based system, at least on the surface of things, has turned into a lifetime constitutional monarchy, is now somehow protected by the Finnish employment laws and in everyone’s best interest. Although here from the eyes of an outsider, this stability feels like stagnation: something that ensures the position of power and modus operandi do not change.

In the monologic narrative, you published titled On the speed of change, there’s a talk about the speed of change and how challenging it can be and how naturally time-consuming it is to go through small reforms in the structural systems and decision-making boards that are in place. As I was reading it, I felt the shadow of Rosa Luxembourg behind me saying “Its only consequence would be a slowing up of the pace of the struggle”.3

Let’s be clear. It’s very important how you define the idea of meaningful change since there are two very distinct approaches to change.

Are we talking about a gradual change that suits the people in power the most? Because that’s exactly what the text published in Frame’s blog in response to our struggle conveys. A gradual reform aka change from above4. This means that we, the disenfranchised, need the people in power, the same people that benefit from our oppression, to tell us how to struggle. Although they never have been in our shoes, we still need them to tell us how feasible our hopes, dreams and goals are and how long it takes to achieve them. This so-called change, simply ensures that the structures stay the same and there’s a reason to preserve the status quo.

Here, we are conditioned to think that these problematic structures which disregard us and push us away are normal. That our dreams are not achievable in our lifetime and we need to sit and wait for our more privileged peers to take their time and attend a million workshops that may enable them to imagine a fairer, more inclusive working environment that can contain us too, while we spend our lives competing for crumbs and handouts. They love to tell us exactly what we want and how long it takes to get there while making sure that structures that support the existence of ideas that legitimize them, stay in place.

But there also exists another kind of change. A change from below4. A revolutionary mindset as opposed to a reformist one. One whose margins are not defined from the above. One whose shape and extent are determined by the situation we find ourselves in. One that feels no obligation to serve the stagnant structures that have brought about its necessity and one that doesn’t need the existence of those structures to legitimise its existence. Dear Frame, do you think you’re up for that?

External training and workshops for the privileged and performative deconstructions from above are not going to change our situation. What we need here is an actual alteration of roles, people, systems and structures that have brought about and benefit from the way things are.

We are all too familiar with not being seen, not getting the jobs for which we’re overqualified and our state of dire precarity not being acknowledged. What infuriates me and many like me is when institutions and people associated with them, through social media or other platforms, claim to be allies, and paint a picture of support and togetherness when it comes to the struggles of people of color or other minorities, both domestically and internationally, without acknowledging their own role in the situation those people are facing. Rehearsing Hospitalities5 is meaningless without love, accountability and generosity.

‘Recruitment’ Instagram Story highlight by Frame in response to comments made on the Instagram post referenced in the text, 2021

Dear Frame,

If you really want to help, there are many concrete steps and solutions. I’m sure if you organise a conversation dedicated to finding alternative ways of operating instead of taking it upon yourself to come up with what’s best for us, that would give rise to many more thoughtful suggestions.

Here are my personal suggestions for the time being, to the so-called “white allies”:

If your support goes further than words and you really want to help change things in an attempt for a more inclusive, accepting future, give these options a thought:

- If you’ve worked for more than five years in a leadership-level position in an institution that seems to continuously struggle with the issues that are raised by this text (most cultural institutions in Finland), and you really want to help change things for the better, please quit your job! You’ve been in your position long enough and your efforts don’t seem to really create meaningful changes. By giving up your position you at least may contribute to a new beginning.

- If you’re in a full-time permanent or long-term leadership position and you do not want to leave your job, think of suggesting, to the board, the creation of a new position by reducing your hours. If two full-time members change to 75% work, that opens up the possibility for hiring a new 50% employee, not an intern, who can be on a revolving basis and with whom you can share your responsibilities. This would contribute to on-the-job training for future leaders and open a position without the need for further financial resources. And we all know 75% of a leadership position salary will not really reduce your quality of life drastically.

For now, however, as James Baldwin puts it “I can’t believe what you say,” the song6 goes, “because I see what you do”7. You talk about transparency, your intentions, values and hopes and all I hear is the sweet voice of Tina Turner singing:

Uh, uh-uh, uh-uh-uh, uh, uh-uh

(I can’t believe what you say, because I see what you do!)

Mm, mm-mm, mm-mm-mm, mm, mm-mm

(I can’t believe what you say, because I see what you do!)

Uh, uh-uh, uh-uh-uh, uh-uh-uh-uh

(I can’t believe what you say, because I see what you do!)

Mm-mm-mm-mm, mm-mm, mm-mm-mm, mm-mm, mm-mm

(I can’t believe what you say, because I see what you do!)