Portrait of Sasha Huber. Photo by Kai Kuusisto.

Marcia Harvey Isaksson (b. 1975, Harare) is an independent curator, artist and the founder of Southnord, a platform that makes space for black and afro-nordic artists. She previously ran Fiberspace, an award-winning arena for textile art, craft and design. In her artistic practice she explores our common cultural heritage, using textile techniques as a vehicle to navigate her investigations.

I first encountered Sasha Huber’s work via social media a few years ago. I am no longer sure which piece I saw first; it could have been her portrait of Rosa Emilia Clay, the first black woman to receive Finnish citizenship back in 1899, or perhaps just a close-up detail of the intricate staple gun patterns that arise in the making of the work. All I know for certain is that as soon as the image was imprinted in me, I was compelled to dig more into the oeuvre of this artist. The world that revealed itself was a visually striking, factually fascinating, emotional roller-coaster ride. The sense of pride I felt, as a black person in the Nordics, learning of the lives of the inspiring forerunners portrayed in The Firsts series was intricately intertwined with outrage at the history of erasure that had obscured their fates. Sasha Huber is like an archaeologist, transcending time and space, patiently sifting through the remnants of history to reveal multiple truths and past injustices, holding both pain and repair within her practice.

This interview takes place at a point where Sasha has gone from being a stranger admired from afar to being a dear friend and advisor. I have been following her work intensely over the last two years, the culmination of which, for me, was attending the opening of her solo show You Name It at Turku Art Museum in June 2023. This impressive gathering of over fifteen years of work laid out the tangled web of peoples, histories and geographical locations, all tied to the racist legacy of Swiss American Louis Agassiz (1807-1873), a biologist and geologist.

MARCIA: What struck me when we were in Turku for the opening of your exhibition, besides the wealth and sheer number of works, was the pulling of the many, many threads of your work into one space. Despite being seemingly unrelated at first glance, these different threads are all interconnected. You mentioned that when you started the project, you had no idea where it would take you, and I’m curious to understand if your method of working, of digging - both digging down and digging outward - is something that you’ve always had in you or is it something that has developed through this work?

SASHA: That’s interesting that you ask in this way because it reminds me of thinking back to before I was an artist, already as a young person, I always took the initiative and was proactive. I did not necessarily wait for something to come to me, but more based on the ideas that I had, I went out and achieved them somehow. I think having good experiences from this way of working has helped me to continue in quite a natural way. Even though, at times, I did things that I didn’t know how they would end up. The seed was planted when I started working with the staples in 2004 when I discovered this tool while studying here in Helsinki. But in a way, when I think about it, based on what you asked, it’s really the attitude itself that I had from the start that allowed me to start on that web, or these roots that go to places that you don’t necessarily know where they lead to, but that connect to other peoples, to other stories and other roots. I am also not afraid of trying out new things. Many things I’ve done, especially since starting this Demounting Agassiz project, were things I have never done before.

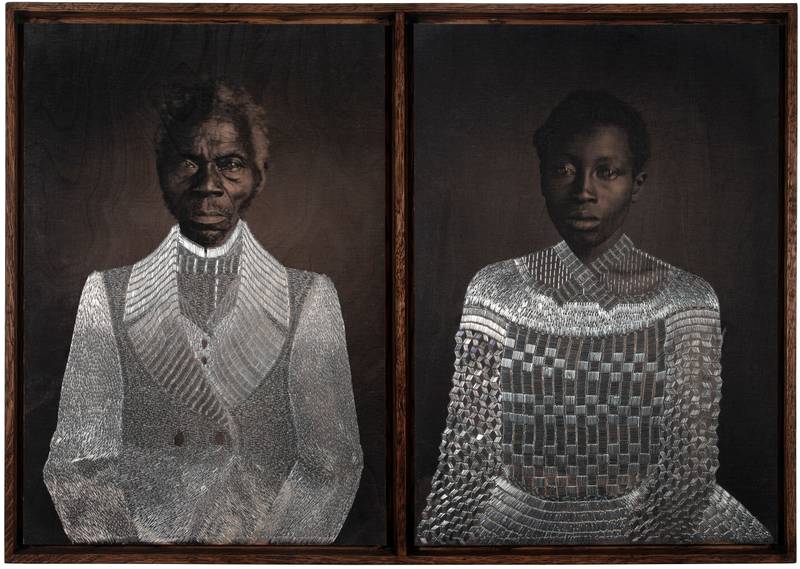

Sasha Huber, Tailoring Freedom – Renty and Delia, 2021. Metal staples on photograph on wood, 97 x 69 cm. Courtesy the artist and Tamara Lanier. Original images courtesy the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University (Renty, 35-5-10/53037; Delia, 35-5-10/53040).

It seems to me that you are very organic in your process; the work and the research you do brings you to a particular door, and you open that door, leading onto a path that leads to other paths, and so you are constantly making choices on which way to go. And that leads you to certain people and situations. Can you give me an example of where one of the choices during this very long project led you to completely new knowledge, a new collaboration, a new way of working, or a shift in your practice?

The strongest moment for me was when I was contacted by the descendant of Renty, his great-great-great-granddaughter Tamara Lanier. That was in 2012. It would have been impossible for me to find her, but she found me and the founder of the Demounting Agassiz Committee campaign, Hans Fässler, a historian and activist. And that was very powerful because it told me that I can reach people somehow with what I’m doing. In this particular case, it was because of the petition website that her daughters found out what this renaming idea was about. The Demounting Agassiz campaign was founded with the idea of renaming the Agassizhorn in the Bernese Alps, to be renamed after Renty. Renty was from Congo, an enslaved man whom Agassiz commissioned to be photographed in 1850. He tried to use these photographs to ‘prove’ the inferiority of black people. So, the idea was to honour Renty and people who experienced a similar fate. And I was already wondering who from his family was still alive today. After they found this initiative, they came to Switzerland and spoke about Renty. She gave him his humanity back and said that he could read, for example. That was very powerful. We are still in touch.

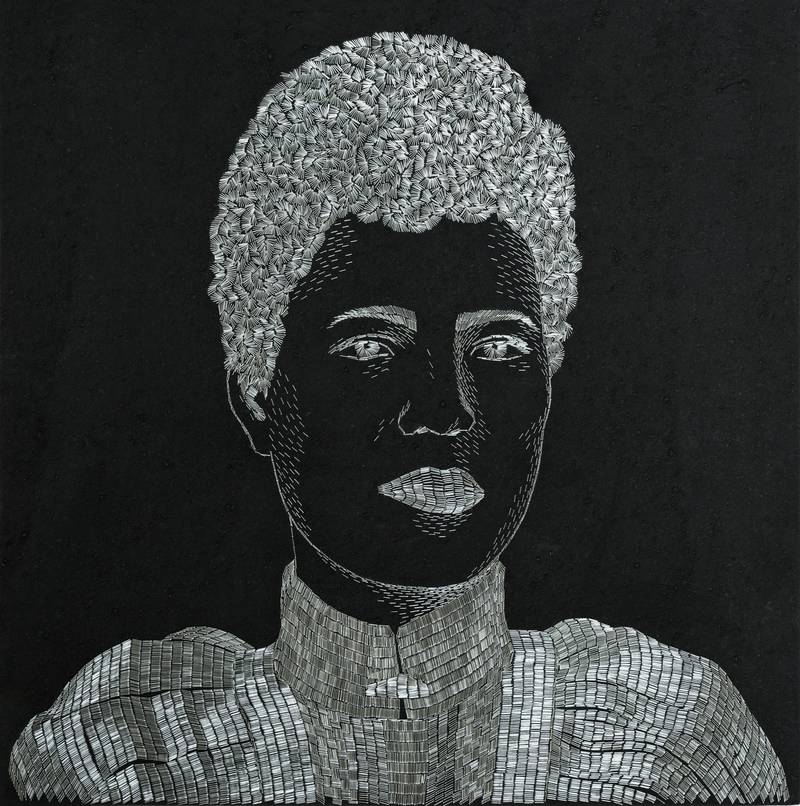

Sasha Huber, The Firsts - Mazahr Makatemele (1846-1903), metal staples on black painted acoustic board, 100 cm x 100 cm, 2023

Sasha Huber, The Firsts - Rosa Emilia Clay, metal staples on black painted acoustic board, 100 x 100 cm, 2017. Private collection. Courtesy of the artist.

I wanted to ask you if you feel that you are an activist. Do you feel that what you do is a form of activism through art? Or are you just making your art and telling stories that fill in the gaps in history? And those stories happen to be political?

I don’t call myself an activist. Rather, a visual artist-researcher. However, my work often deals with political issues from a decolonial perspective, and in this way, my work can be described as visual activism. When I started making art, I wanted to say something about the colonial history that impacted my own family history and everyone’s life, even those who don’t think that is the case. My father is Swiss, and my mother is from Haiti. I have many different stories in my family, so it helped me make some more sense of the world we live in. It is allowing me to shed light on histories that have been silenced in the past, and it looks at the blind spots. It’s good to be unafraid to go there, even if it’s painful.

I wanted to touch on the pain. When you started using the stapling, you were literally fighting back, shooting back. Then you started stitching and healing instead, even through these painful stories. Why this transition?

The stapling became the stitching of the colonial wound. The important transition that took place was in calling this work pain-tings, which includes both - the power of the pain that is inflicted and, at the same time, a way to heal transgenerational wounds that continue to be there. I realised quite soon that I was using my energy in the wrong way, as in the case of my first portraiture series titled Shooting Back from 2004. I wanted to stop creating portraits of people who did so much damage because the end result is a portrait of that person, and I don’t want to look at them anymore. They’ve been written down in history; they’ve been seen so much. That made me shift and bring my attention to people’s histories that have not been written down or not been listened to enough and have been silenced in the past. And so, it also becomes this method of care and memory.

Remedies (Sasha Huber and Petri Saarikko), Sanctuary, mist, 2023. Commissioned by Helsinki Biennale/HAM. Photo: Petri Saarikko

Your partner Petri Saarikko and you collaborated for the Helsinki Biennial 2023 with an installation in a pond called Remedies - Sanctuary, mist, a beautifully sensitive and poetic intervention. Can you talk more about the collaboration, which is kind of a shift from your solo practice?

We are both artists in our own right. But that project, Remedies, is something we started together in 2010 during a residency in Sweden. We developed this project because we were gifted remedies from our families and wanted to connect to people to speak about their family knowledge that has been transmitted orally. Remedies are so ubiquitous that often, one doesn’t even realise to have such knowledge. We worked on this project during most residencies, for example, in Aotearoa, New Zealand, Australia, Haïti, Germany and now in Finland. We did a public artwork also under the name Remedies, where we made permanent sculptures with the community. And then the Remedies for the Helsinki Biennial on Vallisaari was the first time to work in nature, which became a collaboration with nature itself. It was a beautiful place with a particular history, and it was important for us to create a work that interfered as little as possible with the environment, so we created a kind of natural phenomenon that was made from the water of that pond.

For the Southnord project, I reached out to you to advise, guide and help navigate the Afro-Finnish art scene. You and Nimco Hussein really welcomed Nkuli Mlangeni-Berg and me in a beautiful way, a soft landing in a space that we had no idea about but were curious about. You both put much effort into planning and organising the two-day workshop, including studio visits. The whole Southnord project has been built on the knowledge of other people and will continue to be built in that way. No one person can do all of this, it takes a village… You’re a connector of people, you are engaged, and you dedicate yourself to other people’s projects. So, I wanted to ask you about that side of your practice that you maybe don’t talk about so much - where you’re mentoring, where you are organising, where you are facilitating and making things happen for other people.

Yes, I love to connect people. I see when people need to meet each other, and I connect them. Somehow, it comes naturally to me to do that. It was nice to have you in Helsinki and to host you and introduce you to everybody you need to know, resulting in a snowball effect. I enjoy that. After introducing you to NO NIIN, we are now closing the circle, and it’s great that we get to talk together here. When I work collaboratively or by myself, it’s always about connecting to the right people who are engaged and excited about different things one works with. My work with the staple project is very secluded, I’m isolated. I have to wear earmuffs and protect my ears and eyes. So, it’s quite lonely work in a way. It’s important to me and not just be in the studio, like the research work I’m doing, which is collaborative, participating in conferences, contributing to different projects, etc.

Sasha Huber, The Sea of the Lost, metal staples on wood, 355 x 120 cm, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Saastamoinen Foundation Art Collection / EMMA – Espoo Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Ari Karttunen/EMMA

You are also one of the twenty exhibiting artists in the Southnord exhibition at Kulturhuset in Stockholm, The Threshold is a Prism. One of the largest pieces in the show is your work, The Sea of the Lost (2016), a striking boat-shaped piece where you used your staple-gun technique to make the waves on the wooden surface. I think it was the 200,000 staples you used. I find that piece to be so poignant to have as the first piece visitors see when entering the exhibition. Can you share your thoughts on it?

That work is made as a way of commemorating people who didn’t survive the Middle Passage, about two million uprooted, kidnapped Africans. They were brought over the Atlantic Sea in the most horrible way, stacked like goods. So, each staple remembers one of these people who died. In a way, it is incredible to think that there are people who are alive today who come from people who survived such horrors. Then it also remembers people that didn’t survive the so-called Mediterranean Middle Passage in our lifetime now, you know, so many people die today that are not supposed to die in this way. One could say it links the past to the present.

Closing words, as I said, I’m glad that this is the first piece that the audience will encounter when entering the space. We need to take a moment to really remember and reflect on how all of us who are in the African diaspora living in the Nordics got here. We came through so many different trails and sacrifices that others made. There are so many stories, and I think your practice, in general, is very good at lifting these stories and showing the depth and breadth of each story and how interconnected these stories are.

Yes. In the words of Ambalavaner Sivanandan, a Sri Lankan political essayist and anti-racism campaigner who was based in London: We are here because you were there.