Illustration by Alejandra Aguilar Caballero

Patricia Carolina (she/her) is an artist living and working between Oslo, Mexico City and Reykjavik, she is also a member of Verdensrommet, a mutual support network for non-eu art workers in Norway. Through moving image, installation and text, Patricia’s practice deals with domestic and urban environments, where lines of water and waste serve as channels to talk about migration, grief, and growth.

Paola Jalili (she/her) is an artist-publisher and cultural worker currently based in Helsinki. In 2021, she started Ei Mainoksia, Kiitos!, an independent art publishing initiative that aims to prioritise care and highlight the time and labour behind the act of publishing. She is part of Feminist Culture House, a curatorial and editorial platform that works with and for underrepresented artists, and produces tools for more equitable collaborations within the arts. In her visual arts practice, Paola reflects on the intersections of labour, gender, and the contemporary workplace through the project Office Aesthetics.

We met for the first time last fall while participating at Kuno’s annual meeting, a network of fine art schools in the Nordic-Baltic region, celebrated in Turku in 2022. Both of us migrated from Mexico to Europe to study arts. After graduating, we have experienced many difficulties in continuing our careers in the Nordics—Patricia in Oslo and Paola in Helsinki. It didn’t take long before we started mapping the similarities and differences between our positions.

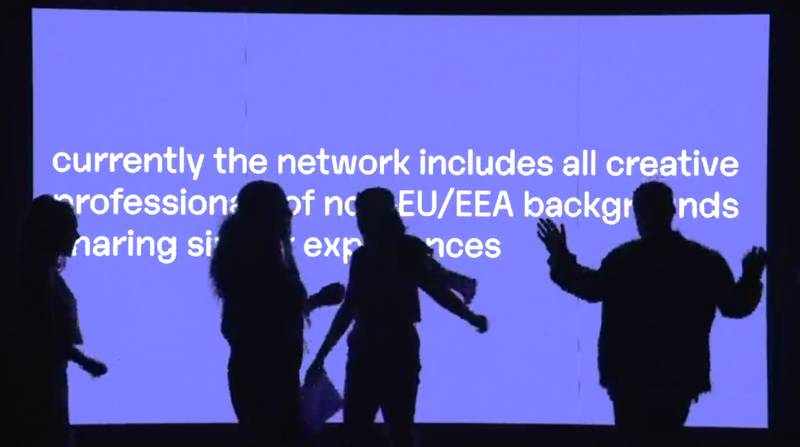

Patricia works with Verdensrommet, a network for non-eu/eea creative professionals based in Norway, and Paola hosts a peer group for non-eu artists, students, and arts workers in Finland as part of her work at Feminist Culture House.

We were both thrilled to meet in this serendipitous way and stayed in touch, knowing we would do something together in the future. Our dreams and ideas for collaboration are still fermenting, and while we wait for them to be ready, we present here a selection of our exchanges over the summer of 2023. Here you will find three sections that reflect our common and most urgent interests, always intertwining the personal and the collective in mutual support and in permanent search of alliances.

Verdensrommet and Feminist Culture House: Advocacy work towards non-eu artists and creative professionals in the Nordics

Paola: Can you tell me what Verdensrommet is and how it started?

Patricia: Verdensrommet is a mutual support network held for and by non-eu/eea art professionals in Norway. For me, Verdensrommet has been an alternative to the deep bureaucratic voids, a tool box, a panic bottom, and a place to meet others under the premises of care and mutual responsibility. The network was born in 2020, when the covid-19 pandemic made evident the already precarious conditions in which certain groups were living and working. I had just moved to Oslo to study. I was unable to source my income from part-time jobs at cafés and restaurants since these places were closed; the lack of contacts and the language barrier also made it difficult to access better positions. Although many students shared this issue, if you had a non-EU passport and were a student in Norway in 2020, it’s likely that you were not eligible for unemployment insurance or any other social program that your EU peers had access to to ease the effects of the pandemic. Another common problem was the long waiting times for the processing of residence permits: papers were handed after 9 or 10 months, bringing a lot of uncertainty to people who were already in the country. As questions piled up at the immigration offices, people were getting information from each other.

It is not that these conversations were not happening in our community before; over a coffee or a beer, people under certain migratory statuses have always found ways to meet each other. Verdensrommet brought a shortcut; now migrant artists in different parts of the country can come across regardless of where they are based.

That’s how, in late March, Rodrigo Ghattas (Peru-Palestine) and Gabrielle Paré (Canada)—two young artists living in Norway—created a Facebook group named “Verdensrommet”, a place for non-eu creative professionals to voice their concerns, share their cases, and exchange opportunities. It is not that these conversations were not happening in our community before; over a coffee or a beer, people under certain migratory statuses have always found ways to meet each other. Verdensrommet brought a shortcut; now migrant artists in different parts of the country can come across regardless of where they are based. After a few months, the Facebook group gave rise to a website, several events, and publications, and our network had more than 200 members registered. Verdensrommet collaborates with a growing number of allies in the Nordics, Italy, the US, and others.

Regarding the way we work, Verdensrommet is volunteer powered, so in different capacities and periods of time, various members facilitate, coordinate, and mediate specific programs, such as gatherings and workshops. I had been using the tools of the network since it was created, and in 2022, I decided to become more active in the working group next to Prerna Bishnoi, Sarah Kazmi, and Rodrigo Ghattas. Currently, we are coordinating Aliens Network, a transnational effort between grassroots organisations working in the nordics. We hope to map singularities, find meeting points and bring awareness about the challenges of being an immigrant self-employed artist working in the eu/eea region. The first meeting of Aliens Network will be celebrated on the 9th and 10th of December in Oslo.

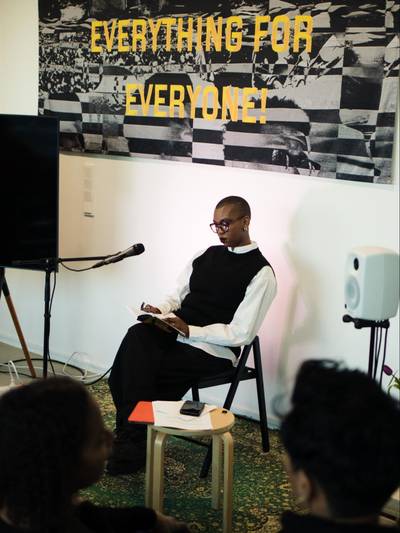

Verdensrommet Retirement Rave at FSS, Oslo 2022, Image courtesy of Verdensrommet Network

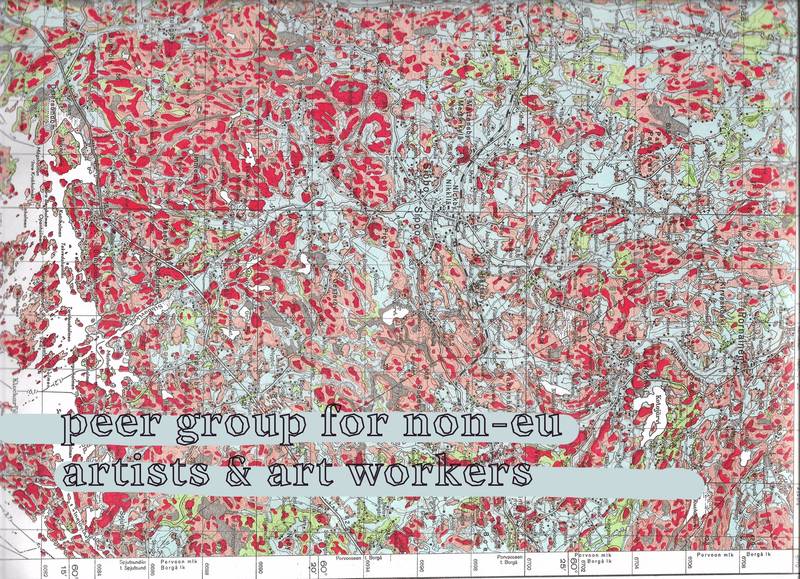

Poster for peer group for non-eu artists, organised by Feminist Culture House, Helsinki 2021, image courtesy of Feminist Culture House and Paola Jalili

Paola: Similarly to what you said about Verdensrommet, I see our peer group for non-eu artists as a collective source of knowledge in response to the opaqueness of the Finnish Immigration Service (Migri).

This peer group was initiated by Feminist Culture House in 2019—before I joined the platform. As you said, these issues have existed here in Finland for a very long time, way before this group was initiated. Then around 2021 I joined the peer group as a host (a paid job with a contract that allowed me to renew my residence permit at the time), and later I joined FCH as a core group member, which I still am.

At the same time, FCH also hosted two more peer groups: one for racially underrepresented artists and one for non-binary and trans artists. While the three groups had many things in common, the main difference the group for non-eu artists had was a very concrete need for support in terms of the administrative and bureaucratic tasks that exist when you are a non-eu resident in Finland. And in the case of artists and arts workers, your residency status is often impermanent, precarious, or a constant source of stress and anxiety, so peer support and community felt very important.

Patricia: I can totally relate to the need of feeling understood and accompanied while going through immigration processes. A lot of people feel that dealing with inequality is a private matter, and this is too much for a single person to handle. Before moving to Norway, I tried for three years to base myself in Iceland, Italy, and Germany, and I did not find a large community of people to feel understood. Can you tell me more about how you structured your peer group in relation to this idea of going through these processes together?

Paola: When I joined as a host, we thought that the peer group could become a very practical space, a concrete way to accompany people navigating immigration bureaucracies as artists and cultural workers in Finland. Migri is a very opaque system, and all the information they publish is very ambiguous and open to interpretation. After dealing with them for a while, you realise that they are quite unregulated—they may give very different decisions to different people who submitted almost the same residence application, for example. Sometimes it feels like the system is designed for you to fail. It seemed that the only way to understand and interact with this system was by gathering as much information as possible from those in similar situations. So our peer group became a place where we could all get together and share our collective knowledge on how to deal with residence permits and other immigration processes as artists, art students, and arts workers.

As documented migrants, we must spend a lot of time researching and reading between the lines. There is a lot of pressure on interpreting information correctly and a fear of not doing things right. This can feel very personal and isolating.

In 2022, we organised a series of sessions to share this information and find different ways to support each other. In preparation for this, I started making a mind map where I put all this information that I had on my head, all these tips that my friends had told me, and all the things that I and others had learned from good and bad experiences with Migri. As I started mapping all of this, I realised it was a massive amount of information—most of it was about dealing with immigration authorities, but also about other practical things like taxes, artist unions, unemployment benefits, etc. Because, as you also know, many things that apply to eu folks don’t necessarily apply to non-eu folks.

Unfortunately, FCH doesn’t have funding to continue doing this work, but we still try to keep this group semi-active by updating our map and through a Discord community where any non-eu artist living in Finland is welcome to join.

Patricia: We need to request more sustainable ways to keep our projects afloat because the work of organisations like ours is crucial. As already hyper-performing individuals, many non-eu art professionals find it difficult to follow each immigration policy while feeling compelled to understand each reform since their permanence depends on it. We agree on this: communication with immigration authorities is demanding; official websites are saturated, hard to navigate, and even ambiguous. As documented migrants, we must spend a lot of time researching and reading between the lines. There is a lot of pressure on interpreting information correctly and a fear of not doing things right. This can feel very personal and isolating.

I don’t believe our network is full of experts in immigration policy, but nonetheless, everyone has relevant experiences dealing with structural disparity. Verdensrommet gathers collective knowledge, transforms it into tools for others to make more informed decisions, and brings companionship—we are many going through the same process.

Paola: This reminds me of a wonderful project by Harold Hejazi, an artist based in Helsinki, called Adventures of Harri Harri. It is a live performance / role playing game in which the main character is a non-eu artist living in Finland. So during the performance, you could roleplay and experience his daily life. There’s an amazing part in that game where Harri Harri goes to Migri’s website and tries to submit an application for a residence permit, and the screen becomes a Mario Bros. game lookalike, and the main character has to jump all these floating structures in order to reach the 4 year residence permit, but even if he jumps as high as he can and uses all the tools he has, Harri Harri can never reach the 4 year permit. It’s such a good way of illustrating the difficulties of dealing with a bureaucracy designed against you.

Patricia: It is definitely a good example of how migration and meritocracy are linked. It is not enough to be qualified as a worker or professional; that means nothing if one is not skilled at handling bureaucracy too. It is always sad when a permit is rejected. I wonder who is there to be accountable for that. It is always the applicants, either for not being “enough” something, for having lives that don’t fully fit in the given permits, or for misunderstanding ambiguous information. I think there is little being said about the unrealistic expectations from these authorities and the violence of the structures gate-keeping wealth that has been built collectively. Not a fair game! Can we actually come out victorious from something like this? We need better tools and fairer policies.

From the Personal to the Political: Education, culture, and immigration in Norway and Finland

Patricia: We are two non-eu/eea art professionals living in the same part of the globe. You in Finland and I in Norway are witnessing the rise of the extreme right: hostile policies that seem to be contagious. A very recent example of this is the introduction of fees for non-eu/eea students in Norway, erasing the principle of free education for all that had ruled in the country for decades. The proposal was implemented in 2023, just weeks before the minister of education and main promoter of this damaging reform, Ola Borten Moe, got forced to step out of his position due to a scandal involving millions of kroner and corruption.

Those refusing education as a basic right for everyone in Norway argued that if degrees are not free in other countries, why should they be free for foreigners in Norway. Sweden and Finland—where tuition fees for non-eu/eea students were also implemented in 2011 and 2017, respectively—were taken as successful examples. To what extent was exposure to different ideas jeopardised, access to the same opportunities to thrive lost, and discrimination legitimised? All of this, inside the classroom. There is a lot that will be lost.

As of today in Norway, people without a European passport have to pay between 44,000 and 64,000 euros per academic year to study a bachelor or master in arts, design, theatre, dance, etc. Who can spend that money? I don’t believe that the school from which I graduated in Oslo just in 2022 received any new non-eu/eea students this year.

You can imagine how painful this decision was for the art community; many expressed their concerns months before its approval; nonetheless, outside of student organisations, the lack of media coverage was frustrating. Maybe it did not provoke as much condemnation in Norway because the aggression came masked as a reform in education and not as a change in immigration policy—as it was, after all. A lot of young people migrate to the Nordics through studies. It sounds like in Finland too, the attack on the principle of free education in 2017 became just the beginning of a series of repressive measures.

Paola: Yes, I actually moved to Finland in 2017, the first year they started charging tuition fees to non-eu students. I didn’t have to pay anything because I got a 100% tuition fee waiver, as many did and continue to receive, but not every student can get one, and the rules of who gets one are not clear, or at least they weren’t when I got it. It feels quite shocking that in Norway there aren’t any kinds of scholarships or waivers for non-eu/eea students, which makes me think that the educational landscape in Norway will transform way faster than in Finland.

But now that we are talking about students and education policies, I think I should also mention the new Finnish government. It is a far right, very conservative, very anti-immigration government. Their government plan has several proposals that aim to dismantle the welfare system in Finland, tighten the restrictions for immigrants living and working here, reduce the quotas for refugee intake (making it one of the strictest countries for refugees in Europe), set back protections against the climate crisis, and many other points that affect those who are already the most vulnerable in the country.1 So many of us are very worried about this.

It’s been quite impressive, though, to see so many protests and demonstrations against this new government. They have been organised since their new plan was announced at the beginning of July and keep happening every few weeks. At the time of editing this text, many universities and other educational institutions in the country had been occupied by students as a form of protest against the planned budget cuts in housing benefits and mental health support, as well as the racist immigration policies that would also affect international students.2

There have also been a lot of protests and actions organised by groups of immigrants because, as I said, the new government is targeting them quite strongly. It’s been great to see this political momentum, but it’s also been hard to see how some of the groups that claim to be protesting in the name of immigrants use a very neoliberal rhetoric that advocates for the rights and treatment of immigrants on the basis of them working and producing taxable income. All of this is summed up in one of the phrases that we’ve been hearing a lot in demonstrations: “Same taxes, same treatment.” I am horrified at this because the right to reside in a country, or the right to be treated like the rest of the people who live in that country, shouldn’t be tied to your capacity to produce taxable income. Thus, many aspects of a thorough critique of the racist and anti-immigration policies that this new government is trying to implement get lost, but fortunately, there are also other groups advocating from an intersectional perspective, and hopefully that’s the one that gets through.

Within and beyond: Creating allyship in the creative field and across borders

Paola: In another conversation we had, you mentioned a sense of difference between non-eu art professionals and their Norwegian and European peers and how this sometimes makes it hard to create alliances amongst both groups. Can you tell me a bit more about this?

I wish the authorities would be willing to see how artists work, recognize the non monetary value that we produce, and facilitate a permit that does not treat creative professionals as entrepreneurs. Meanwhile, solidarity from our peers is important, as is understanding the nuances of the precarity we face; more engagement from our artist unions and cultural institutions with the immigrant-artist agenda is also needed.

Patricia: Norway is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. Two large new museums were just opened in Oslo: the new Munch Museum and the new National Museum for art, architecture and design—the last one becoming Norway’s most expensive ever cultural building.3 It is ironic that economic insecurity is one of the biggest worries for creative professionals living here. National budgets for culture, art, and education are shrinking year by year, and on average, people in the field whose income is sourced exclusively from art-related jobs live below Norway’s poverty line. Almost all my artist friends here have side jobs in other areas to maintain their practices. But let’s remember that if you are a non-eu creative professional, immigration law prevents you from working in anything different from the field that you were qualified for. I hold a master in fine arts from the art academy in Oslo, and I produce different forms of value for which I am not always economically remunerated. I have professional and affective relations in Europe, and I want to stay here; my only alternative was to take a self-employed visa. People with this type of permit are excluded from accessing a mixed economy with site jobs to make a living—a right that our European colleagues have. We are also compelled to make a net profit of around 30,000 euros per year, only from art-related activities, as one of the requirements of the residence permit. I wish the authorities would be willing to see how artists work, recognize the non monetary value that we produce, and facilitate a permit that does not treat creative professionals as entrepreneurs. Meanwhile, solidarity from our peers is important, as is understanding the nuances of the precarity we face; more engagement from our artist unions and cultural institutions with the immigrant-artist agenda is also needed.

In 2022, Verdensrommet hosted the first Immigration Clinic, a two day seminar where we brought together case handlers from the Norwegian immigration authorities (UDI), members of the largest artist unions in the country (UKS, NBK, OCA), politicians, and lawyers to talk to each other and to make them aware of the contradictions that we must overcome as non-eu creative professionals with a self-employed permit in Norway.

Verdensrommet Immigration Clinic for Creative Professionals, Oslo 2022, Image courtesy of Verdensrommet Network

Paola: Many people from our peer group—including myself—have also needed to apply for a similar permit for entrepreneurs, since that’s the only framework that sort of matches the precarious and irregular work we do as artists and cultural workers. And even though it’s been a way for many to continue living here, it comes with a whole new administrative and bureaucratic aspect that adds to your already overworked schedule.

There’s a very interesting text written by Emmanuele Braga in the book Art for UBI (manifesto), where he explains that the precarious working conditions that artists have been enduring for decades are now the blueprint for many transformations in the contemporary labour market at large. In other words, the precarization in the art field is now used as a model to precarize other sectors as well. And that relates a lot to this common thread of us having to become “entrepreneurs” in order to prove that our work is valid to immigration authorities.

It can sometimes be very hard to communicate the lived experiences of non-eu people and how, even if we are all working in the same precarious field, we are not working under the same conditions. For example, sometimes you cannot travel for work because you’re waiting for a residence permit, while your European peers are free to move across the eu.

This also takes a lot of emotional labour, sharing this with others, even with your friends who are non-eu. And it’s not that people aren’t empathetic or outraged by this; they are. I guess we just need to visualise these conditions, not only in our field but on a larger scale, to change these structures.

Patricia: Right! My close friends are aware of how I feel during the periods of visa renewal, we talk a lot about immigration. They might not fully relate to my experience, but they offer their support and understanding. Maybe they talk to their other friends and families about it too, and little by little, there is a more realistic approach on what hostile policies do to communities.

I also believe that eu and non-eu/eea artists have many common goals and reasons to look after each other. Verdensrommet focuses on the challenges of being a non-eu creative professional, but also demands better conditions for everyone in the field: housing, working stability, and support structures. Mutual responsibility and care are a shared work that continues to be done after the residence permit of one individual in the network gets granted.

Paola: One of the first times we talked, you said that what happens in Norway should not only matter to people living there, but that it should matter to all of us. And the same for Finland, or any other country, of course. I keep thinking about this and find it so important. Maybe we can close this conversation with that idea.

Patricia: Absolutely, I am glad that we got the space to extend the conversation between our groups. As far as tools, community, and better conditions are in need; collective action and international solidarity will keep us working.