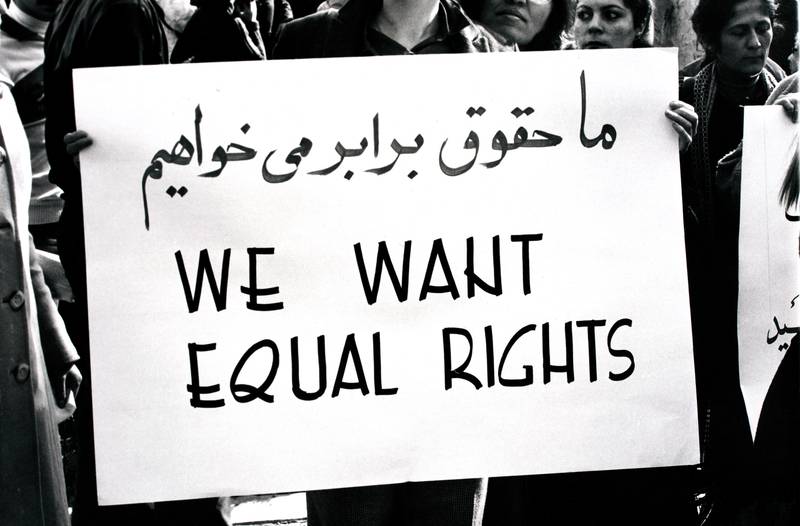

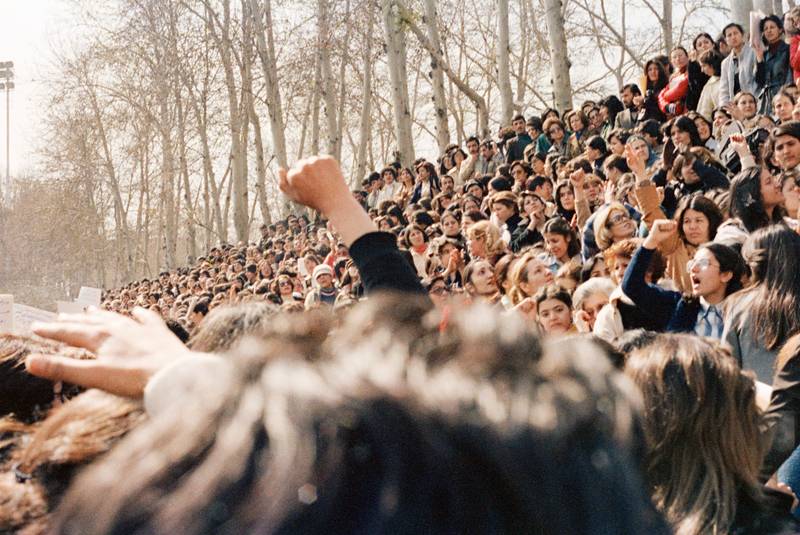

Sophie Keir, Iran, 1979. Courtesy of the Centre Audiovisuel de Simone de Beauvoir.

Sini Rinne-Kanto is a Paris-based curator, researcher and PhD candidate. Her research and multidisciplinary curatorial practice are situated at the intersection of visual arts and design, with interests in interiors and domesticity, collective identities, sociopolitical narratives and feminist practices. She is the Co-Founder and Head Curator of The Community. Her recent curatorial projects include the Houses of Tove Jansson exhibition.

The group exhibition Trailblazers: Feminisms, Camera in Hand and Archive over the Shoulder1 maps out the history of second-wave French feminisms and the interconnected struggles through the founding of the Centre Audiovisuel de Simone de Beauvoir. Curated by Nicole Fernández Ferrer and Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, the exhibition structures around the archives of the Centre Audiovisuel de Simone de Beauvoir, which are set in dialogue with works and contributions by over 40 artists and collectives.

In the opening sequence of the video work S.C.U.M. Manifesto (1976), two women, captured through side-profile shots, sit at opposite ends of a table. On the right, Delphine Seyrig, the star and muse of the French cinema d’auteur, delivers a monotonous diction from the book she holds in her hands:

“Life in this society being, at best, an utter bore, and no aspect of society being at all relevant to women, there remains to civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females, only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation, and destroy the male sex.”

Opposite Seyrig, Carole Roussopoulos is engaged in a typically gendered work, noting Seyrig’s words down with a mechanical typewriter. A third protagonist, a TV screen – on which the camera occasionally zooms in and out – is positioned between the two on the table. A screen within a screen, the television emits a continuous iconography of soldiers and parades, coffins and bombs, interrupted by the occasional appearance of the male host, whose voice can not be properly deciphered over the clacking sound of the typewriter and the steady lecture performed by Seyrig.

The video S.C.U.M. Manifesto is a staged reading of the French translation of a book of the same name written by Valerie Solanas in 1967. While Solanas – most famous for shooting Andy Warhol in 1968 – remains absent in the video, Seyrig and Roussopoulos communicate her text in a performative, audiovisual format, the book having run out of print at the time both in French and English. Despite the absence of Solana’s direct implication to any feminist collectives, S.C.U.M. Manifesto has become a classic of feminist reading with its distinctively radical and humorous tone (S.C.U.M. being an acronym for “The Society for Cutting Up Men”). While Solana’s manifesto centres around the idea of the biological superiority of women, the video contains multiple overlapping signifiers worth exploring: an affirmed connection between feminist gestures and technology; the communication of a radical American feminist author to a French audience; the film directors’ (Seyrig and Roussopoulos) presence in the screen; the domestic set-up and props of the video2.

Image from the video SCUM Manifesto, 1967, directed by Carole Roussopoulos and Delphine Seyrig (detail). Courtesy of the Centre Audiovisuel de Simone de Beauvoir.

Delphine Seyrig, Sois belle et tais-toi !, 1976 Courtesy of the Centre Audiovisuel de Simone de Beauvoir.

Care and Communication

Upon entering the exhibition building that overlooks the Seine River in the centre of Paris, the visitor is solicited by an informational wall that retraces the founding moments of the Centre Audiovisuel de Simone de Beauvoir3. Facsimiles of association documents and letter correspondence pinned on the wall, together with early video works, narrate the first years of the Centre and demand the attention of those not already familiar with the facts. A careful selection of attractive black-and-white photographs communicates the association’s activities across its three-story Parisian premises, where the members worked on video editing and organised film screenings open to the public. A compelling presence of women, or rather groups of women, occupying the spaces and the photographs direct the gaze from one frame to another and establish a strong introduction to the exhibition narrative.

Titled “Herstory in Progress,” the first chapter of the exhibition seems visually economical and structurally orthodox, yet proves to be studious, with a cumulative amount of information. Behind the careful document arrangement displayed on the wall, the information is dense, and the inaugural stories of the Centre are interwoven with a reading of the biographical elements of its founding members, along with information on events marking the feminist struggles of the 1970s in France, such as the 343 Manifesto from 1971.4 In addition to the archival video works that the exhibition features, the curators have included a group of contemporary artists as part of the exhibition whose works span diverse media. In the first room, an installation by Leonor Antunes, random intersections (2017), structures and responds to the architecture of the exhibition space. The work, hanging from the ceiling, takes the form of intertwined horse bridles, which, according to the press release, refers to networking and interaction as guiding principles of feminist collectives.5

Leonor Antunes, random intersections, 2017. View from the exhibition “discrepancies” with C.P au Museo Tamayo, Mexico, 2018 © Nick Ash, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and the gallery, Marian Goodman

The archives of the Centre provide a window to the multiple collective struggles that defined its founding moment and the preceding decade, such as the right to abortion, sexual freedom, the struggles of sex workers, and the rights of female political prisoners. Founded in 1982 by Delphine Seyrig, Iona Wider, and Carole Roussopoulos, all militant activist feminists and video makers in their own right, the three had earlier founded together a video collective called “Les Insoumuses”6 (Defiant Muses). The Centre is still active today and devotes its work to producing, archiving, distributing and restoring videos by French and international women directors and various feminist groups. It also functions as an activist organisation with an educational role and works, for example, closely with prisons.7

“Feminist media appropriations” is the title given to the subsequent room, displaying a large-scale screen looping four videos from the archives of the Centre. Sois belle et tais-toi (Be Pretty and Shut Up) (1976) by Delphine Seyrig delves into the film industry’s prejudice against women through interviews with actresses across France and Northern America. In the recorded testimonies, the attitudes and behaviour of male directors face vehement criticism by names such as Jane Fonda, thus offering an example of early media critique and giving actresses political agency. The theme was of extreme importance to Delphine Seyrig herself, who had, around the same time, made a shift from acting in roles that maintained the idea of mysterious, ethereal, and hyperbolic femininity, such as in Last Year at Marienbad by Alain Resnais (1961), towards working with female directors and playing more assertive roles, such as in Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), or regularly collaborating with Marguerite Duras and Ulrike Ottinger. Around the same time - although unarticulated in the exhibition - the film theorist Laura Mulvey coined the groundbreaking notion of the male gaze in her essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, which combined psychoanalytic theories with feminist reading while deconstructing Hollywood cinema narratives.

Along with Jean-Luc Godard, Carole Roussopoulos was one of the first film directors in France to use Sony’s Portapak video system, which had become available in France in 1968. Teaching film studies at the newly founded leftist University of Vincennes de Saint-Denis8 in Paris, Roussopoulos has since early on placed video and technology at the service of feminist and left-wing struggles, practices born in conjunction with the post-68 movements. Sharing her know-how around filming and editing practices with other women and activists, including Seyrig and Roussopoulos, the collaboration between the three soon led to the inauguration of the Centre. The gesture of disobedience and questions of emancipation through new portable video technologies remain the main thread discussed throughout the exhibition. Interestingly, the curated contemporary artworks span multiple techniques and do not necessarily focus on the moving image praxis per se or elaborate on their political potential in today’s context.

Image from the video Où est-ce qu’on se mai ? by Delphine Seyrig and Ioana Wieder, 1976. Courtesy of the Centre Audiovisuel de Simone de Beauvoir.

Françoise Dasques, image from the video La Conférence des Femmes – Nairobi 85 (Angela Davis), 1985. Courtesy of the Centre Audiovisuel de Simone de Beauvoir.

Diversity in Display

Screens of various sizes, programmed to emit multiple videos in a continuous loop, take over the display in the third, larger exhibition room. The exhibition wall text elaborates on how Seyrig, Roussopoulos and Wider were part of a transnational feminist network and how cinematographic devices became one of the main tools in the leftist struggles. The complex discourse that the chapter contains defies the traditional narratives of second-wave French feminism being predominantly a space for white and bourgeois aspirations with strong literary emphasis, as exemplified by Hélène Cixous and the concept of écriture féminine. “Transnational Struggles” transports the viewer across diverse cultural contexts, addressing narratives on identity, representation, and geographically dispersed struggles, seeking to provide a rereading of the French women’s liberation movements and their connection to decolonial struggles.

One of the examples of the archive’s diversity is Genet Talks about Angela Davis (1970). In this 8-minute black-and-white video made by Carole Roussopoulos and her husband Paul Roussopoulos, the politically outspoken French author speaks for the liberation of his friend, African-American scholar, radical feminist, and activist Angela Davis, who had been arrested some weeks before the recording took place in October 1970. Invited for the French television programme “L’invité du Dimanche” (Sunday Guest) on November 8, 1970, Genet denounces the racist policies of the U.S. and expresses his support for Davis and the Black Panther Party. Afraid that the TV broadcaster would censor the clip (which eventually did happen), Genet had also invited his friend Carole Roussopoulos to the TV shoot to ensure that another independent recount would remain of the event.

The images and videos that succeed one another across the screens provide compelling testimonies and broadcast universes that persuade with their revolutionary aesthetic strategies. Addressing the viewer directly, the videos touch upon multiple registers, from denouncing the Vietnam War and the practice of rape and torture in Latin American dictatorships to favouring the Palestinian cause and the Black Panther Party, to name a few examples. La Parole Aux Négresses by the pan-African editorial platform Chimurenga pursues transnational themes by providing a black-and-white drawn map of entangled genealogies of Black Feminism in the French-speaking world, following the title of the classic text by Awa Thiam from 1976. Installed on the wall at the back of the space, Bouchra Khalili’s “The Weaver” (2022) introduces a gleaming, large-scale tapestry adorned by repetitive motifs that are a mixture of Moroccan references and images of the Sony Portapak camera. We learn that it is part of Khalili’s larger installation that explores Carole Roussopoulos’s work as a video maker.

Bouchra Khalili, The Weaver, From the Magic Lantern Project, 2022 Courtesy of the artist and the gallery Mor Charpentier, Paris © ADAGP

Saddie Choua, image from the video Je crois qu’il y a confusion chez vous. Vous croyez que moi je veux vous imiter. #FatimaMernissi, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

Interconnected Struggles

The chapter “Countering Normativity” includes a video by Saddie Choua, which provides a poignant and contemporary critique of the questions of Western instrumentalisation and representation. I think you’re confused. You think I want to imitate you. #FatimaMernissi (2017) is a video partly composed of found footage of Moroccan sociologist and feminist Fatima Mernissi, delivering a critique of Western Orientalism and its relationship with feminist thinking from the Islamic world. Mernissi’s phrase, “You are trying to drive me into your revolution without knowing what my revolution is," opens a meaningful and much-needed angle of discussion after the previous chapter “Transnational Struggles.” The video Les Prostituées de Lyon Parlent (The Prostitutes of Lyon Speak Out) (1975) by Roussopoulos offers a radical testimony of an alliance between feminists and sex workers through conversations among them. Enabling them to communicate autonomously with the help of technology, the video raises important questions related to the labour, visibility, and material conditions of sex workers. The video’s message is further emphasised through a large-scale black-and-white photograph captured by an anonymous photographer showing Carole Roussopoulos with her camera filming Barbara, one of the interviewees.

The following “Disobedient Practices” chapter makes a somewhat full circle with the introduction chapter of the exhibition, bringing renewed attention to female sexual autonomy and reproduction rights. Again, references to the groundbreaking Manifesto of the 343 and the right to abortion are reiterated here, with black-and-white photography of Seyrig captured on the occasion of the famous 1972 Bobigny trial.9 Iona Wider’s Accouche ! (Give Birth!) (1977) delivers a critique of gynaecological violence experienced by women while proposing feminist practices of solidarity. The concluding chapter of the exhibit, “Herstory in Progress,” focuses on the ongoing struggles, the political legacy of the Centre, and the gesture of archiving. A former Cité Internationale des Arts resident from 2013, Paula Valero Comín’s installation Manifestation végétale / Herbier Résistant Rosa Luxemburg (2020-2023) takes the material form of protest placards while creating a connection between the resilience of urban plans, Luxemburg’s Herbier de prison (Prison Herbarium), and women’s struggles. The exhibition concludes with the video Pour Mémoire (In Memory of) (1986), in which Delphine Seyrig returns to the grave of Simone de Beauvoir one year after her burial. The lingering close-ups show images of the flowers deposited on the grave coupled with a multilingual voice-over conveying the messages addressed to the author of The Second Sex.

Paula Valero Comín, Manifestation végétale (Herbier Résistant Rosa Luxemburg), 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

A Space for Prolonged Viewings

An exhibition spanning over fifty years of audiovisual material is manifestly a rhizome-like entity, a complex space in which ideas, threads and generations cross over, resulting in an open-ended framework. The material on display necessitates not only prolonged viewing and a long attention span but also several exhibition visits, fortunately free of charge. To grasp the exhibition and the featured works in their entirety remains almost an impossibility: most of the featured video materials have, for the exhibition’s sake, been squeezed into a couple of minutes’ worth of shots, whereas the original material consists of hours and hours of documentation. The viewing remains scattered at best, leaving us with a question of how to consider and view these archival fragments, especially when placed within contemporary art registers: the selected archival oeuvres encounter a risk of being compressed into easily digestible images whilst providing a historical reading on feminist or leftist movements as undivided factions. One question that deeply divided the French Left in the 1970s was, for example, the Israel/Palestine question: intellectuals such as Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre and Michel Foucault were openly supporting the creation of the Israeli state, whereas figures like Jean Genet and Carole Roussopoulos were aligning with the Palestinian cause.10

The videos contain several layers of intangible layers of information and transcend many historical contexts - people, events, struggles - whose deciphering requires either devoted studying or pre-established knowledge. The use of text materials across the exhibition spaces has been done in a considerate way, yet sometimes with a didactic touch. Unfortunately, the majority of the letters and ephemera remain untranslated and thus inaccessible to non-French speaking audiences. To counter some of the challenges related to accessibility, the exhibition organisers made an effort to propose an active screening programme throughout the exhibition, allowing spectators to view some of the featured videos in their entirety. The event programme also included a talk with Angela Davis and art historian Elvan Zabunyan, organised by the Festival d’Automne, whose recording remains accessible online.

Sophie Keir, Iran, 1979. Courtesy of the Centre Audiovisuel de Simone de Beauvoir.

Decolonising European Feminism

The Paris exhibition ‘Trailblazers’ is the fourth iteration of the exhibition that was previously organised - albeit in slightly different formats - at the LaM Lille Métropole in 2019, the Museo Nacional Centre de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid in 2019-2020, and the Kunsthalle Wien in 2022, and in 2024, it will travel to the Württembergischer Kunstverein in Stuttgart. The previous instalments seem to have focused solely on the archival material and their historical contextualisation For the Paris chapter, the curators have chosen to explore the contemporaneity of these videos, seeking the interstices between art and activism, which seems natural considering how the video archives tie themselves to the cataclysmic present in multiple ways. In some instances, the connections between the selected contemporary artworks and archives seem unarticulated to some degree, or tangential at best. Through the exhibition materials, the visitor learns that some of the artists are former Cité Internationale des Arts residents, leaving us with the question of the opacity of the curatorial process.

While preparing this article, I was browsing through the exhibition catalogue “Defiant Muses,” which was published on the occasion of the exhibition’s previous 2019 instalment at the Museo Nacional Centre de Arte Reina Sofia. C Featuring an essay by Françoise Vergès, a French decolonial feminist activist and political scientist, the author elaborates on the intersection of the French feminist video and the cinema of decolonization. While bringing forward the crucial notion of North-South geographies and how its logic influenced the practitioners and collectives discussed above, she argues how members of different social movements have had difficulty acknowledging their debt to the anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist movements, which had essentially pushed them beyond their European provincialism. Vergès inquires what the feminist filmmakers, such as Carole Roussopoulos, learn from their proximity to the Palestinians, the Black Panthers or other African independence movements.11 The question remains, at least, partially unanswered four years after the text was initially published.

Vergès writes:

“Continuing to harness the study of feminist film to the goal of incorporating it into the pantheon of French cinema and of admitting feminist filmmakers into that pantheon certainly seems to be legitimate as a reparation for forgetting and erasure. But could we make the effort to imagine what a decolonial narrative of French feminist cinema would look like? Its aim would not be to add forgotten chapters or to take figures, hitherto invisible, who do not challenge the framework of the narrative and make them visible. It would be to engage a multidimensional analysis of European feminist film by identifying what it borrowed from the cinema of struggle in the South and what it forgot or passed over in silence. Paying homage to Seyrig’s feminism and her films would mean finally being willing to decolonize European feminism.”12