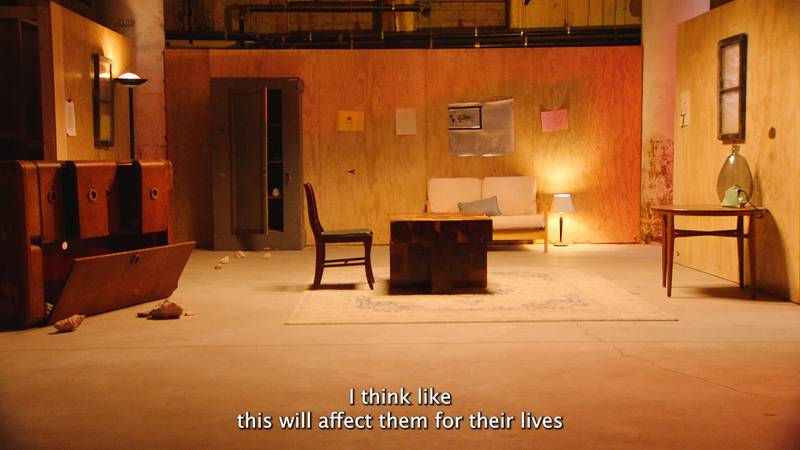

Adelita Husni Bey, These Conditions, 2022, film installation, three-channel high-definition video, 35:46 min., 5.1 surround audio, LCD screens, metal components, dimensions variable. Commissioned by the Vera List Center for Art and Politics. Collection: Castello di Rivoli. Courtesy of the artist and Castello di Rivoli collection.

Alba Folgado is a curator based in Sweden. She received her MA in Curating Contemporary Art at the Royal College of Art, London. Currently, she works as curator at Köttinspektionen, Uppsala. In addition, she is founder and director of ‘A Movement to Hold’, a nomadic archive of artistic representations that focuses on re-visiting critical and non-hegemonic experiences.

Adelita Husni-Bey is an artist and pedagogue whose work focuses on collective educational processes and resistance towards capitalist society. Using workshops, theatre, film and other mediums, her work addresses personal takes on living (and working) in the cracks of capitalist society, unionising, care, and work struggles.

Adelita Huni-Bey and I met for an online conversation around her recent work with “These Conditions," a long-term project that she developed thanks to a fellowship from the Vera List Center for Art and Politics with domestic workers, students, activists and people who had to work in person during the pandemic. This conversation with Adelita felt like the perfect excuse to reconnect. We have worked together before and I am a true admirer of the analytical and pedagogical methods she applies in her artistic practice, engaging people from very different backgrounds into (active) reflections about working conditions, social roles and injustice in capitalist society. At the beginning of the conversation, we focused on this particular way of which characterises her work.

ALBA FOLGADO: How did you come to incorporate pedagogy, radical collective education, and this way of working with people and their concerns and struggles into your work?

ADELITA HUSNI-BEY: At the beginning of my practice, I was quite unconcerned with the idea of producing objects that would be the result of my expression alone and that would enter the market as art objects. I became much more interested in collective processes that had at their root the capacity to produce different kinds of knowledge and to critique experiences of living under capitalism that were both deeply personal but also shared. So, I studied and then utilised some methods that are proper to radical education—forms of education that are inherently critical and not competitive—that have to do with analysing a shared reality.

I picked up these tools from different places. A lot of them are workshop-based methodologies. Many come from anarcho-collectivist education. I’m thinking about Kropotkin’s idea of ‘integral education’, and how without meshing intellectual and manual labour, you cannot produce a classless society. I became very interested in embodied education, in theatre specifically and the ways in which the body offers a way to refute our constant desire to engage the intellect alone, as if there were a kind of mechanistic mind-body split. So re-engaging the body really comes from reflections on integral education and political theatre.

Adelita Husni Bey, These Conditions, 2022, film installation, three-channel high-definition video, 35:46 min., 5.1 surround audio, LCD screens, metal components, dimensions variable. Commissioned by the Vera List Center for Art and Politics. Collection: Castello di Rivoli. Courtesy of the artist and Castello di Rivoli collection.

Adelita Husni Bey, These Conditions, 2022, film installation, three-channel high-definition video, 35:46 min., 5.1 surround audio, LCD screens, metal components, dimensions variable. Commissioned by the Vera List Center for Art and Politics. Collection: Castello di Rivoli. Courtesy of the artist and Castello di Rivoli collection.

This is very interesting, also in connection with the project that concerns us. Last year, when talking about pandemics seemed necessary but, at some point, also repetitive due to the over-information flow to which we had been exposed. You presented These Conditions at the Brooklyn Army Terminal with the Vera List Center in New York. This exhibition was also a pedagogical film set in which you tried some of the aforementioned methods again, although this time in a very different context: a pandemic was going on and many people were living in situations of high stress, burnout and worsening working and health conditions. Can you explain how this long-term project engaged with a group of diverse people within the set?

“These Conditions” is a three-channel film installation. But originally, it was an experience of about two months with a small group of people, including a domestic worker, two activists, a person who worked on the COVID-19 vaccine, two university students and someone who worked in retail and had to go to work in person. None of them knew each other except for the activists.

At the time, I wanted to try to see what it would mean to offer a space where we could meet in person again after a long period of lockdown and to make that space versatile. So I built an actual set that felt mobile. A space in transformation. The walls that composed the set were on wheels, so they could be freely moved by the participants in different compositions. They could create different spaces, and I really enjoyed that as a possibility. I think we all did, because rarely do you get to construct your own pedagogical space, that is, at the same time, the film set within which we collectively came up with theatrical representations of the life that we were living at the time. It was also a very delicate and complex endeavour, and a lot of tension emerged.

We met on Tuesday evenings for about two months after people came back from work and began with rereading some of the pandemic protocols (the legislation), which were written at the time of different pandemics, texts that dated back as far as the 1600s and the 1300s. Some of the texts were really poetic and strange. “Clearing the air with cannon balls” is a citation from one of them. It is interesting to see how different ideological frameworks and the presence of religion really changed the way the powers that be developed authoritative ways of managing populations through protocols.

During the workshops, we started off with warm-up exercises. During an exercise called ‘choir’, I asked participants to memorise parts of some historical protocols and speak them out loud. This led to a cacophony of sound. We also reenacted each other’s memories, often unpleasant and isolating experiences lived during the pandemic. For example, one student felt very trapped staying at her parent’s house. So we reenacted that feeling of entrapment for her, and we had conversations about it. Or a domestic worker who had been left to clean homes for many months while the owners were upstate. She was cleaning their houses in New York, and when suddenly confronted with them coming back, she recounted their need for forms of connection and emotional labor that she hadn’t really accounted for.

Adelita Husni Bey, These Conditions, 2022, film installation, three-channel high-definition video, 35:46 min., 5.1 surround audio, LCD screens, metal components, dimensions variable. Commissioned by the Vera List Center for Art and Politics. Collection: Castello di Rivoli. Courtesy of the artist and Castello di Rivoli collection.

Adelita Husni Bey, These Conditions, 2022, film installation, three-channel high-definition video, 35:46 min., 5.1 surround audio, LCD screens, metal components, dimensions variable. Commissioned by the Vera List Center for Art and Politics. Collection: Castello di Rivoli. Courtesy of the artist and Castello di Rivoli collection.

So, I understand that there are two important questions that structure this project. On the one hand, an analysis of labor conditions during the pandemic(s). And on the other hand, social transformation as a result of capitalist pressure and the change of conditions. As you put it, these axes relate to previous historical situations. How were these references important during the workshops and conversations?

Protocols obviously continue to be used. They are quite different from historical protocols. The ones we read from previous pandemics are sort of strange artefacts. Yet there are some recurring social responses connected to changing material conditions that come up with every pandemic that I’ve been able to study. During the Black Death, for example, where a third of the European population died, there were fewer labourers to go around, and because there were fewer labourers, the price of labour went up. So, people were demanding more money for their time. Rent prices went down. Fewer houses were occupied. The economy was in shock, and in lots of ways, we can see why, for very different material reasons. This incredible wave of strikes is happening in the U.S. right now: General Motors and Stellantis plants, for example. Some of the biggest auto worker strikes in US history. The unionising of Amazon and Starbucks.

This very large and strong union movement is a result of the pandemic and pandemic conditions that were imposed and never fully retracted. The hardships that workers went through were never fully recognised. And these are some of the emergent contradictions -, the ‘sharpening of contradictions’- typical of these historical moments, where capitalism cannot hide behind a magnanimous mask. This was also important during the workshop because participants could relate to these situations and say, ’This is not new; I’m living something that happened to others before’. That was part of the function of bringing history into focus.

Were there any other historical references or examples that were important to the group?

Something else I should mention, and that not many people are aware of, is the fact that transatlantic slavery was in part spurred by pandemics in the colonies. For example, indigenous Bolivian people who were enslaved to mine Bolivia’s silver were dying at very rapid rates because of the harsh conditions they were subjected to and because of disease. So often this part of history is obfuscated, but pandemics have a huge role to play in the deaths of many, many hundreds of thousands of Indigenous people during the colonial period in the Americas which led to colonisers having to seek cheap labour elsewhere, importing African slaves. So this idea of the transatlantic slave route was also very much shaped by colonialism’s capacity to spread disease and use infection as a weapon of ethnic cleansing.

When we were looking at these histories, we became very aware of our own condition. We also began to think about ways that mutual aid had become extremely complex after two years of lockdown. There was a lot of burnout, and the activists enacted their difficulty in organising in isolation, often online, during the pandemic to make sure that services were granted—basic services that the state was not willing to provide. This was also an important part of the workshops, thinking through the complexities and difficulties of living through COVID, the fact that it was not a historically isolated event, and the fact that it was going to occur more and more often. How were we going to be prepared for that?

We have gone through the methods you used in your workshops and the experiences and historical references that you associated with that work. All of these methods and references also seem to structure and shape your practice more generally. A practice that is not only directed at a museum audience, nor is it only an object. Is that the reason you made the space in “These Conditions” look like a film set? Something that was meant to be useful for the participants and rather informative for the visitors?

Yes, precisely. The set was at the Brooklyn Army Terminal. It was organised by the Vera List Center, but it was actually in this very large post-industrial building in Brooklyn, in a working class neighbourhood. As a visitor, what you would see are the walls, which change every week. One week you would see them in one position, and next week you would see them in another position. One week there would be no domestic space; the next week there would be a domestic space.

At one point, there was the story of the gravediggers written on one of the panels. The story of the gravediggers is an interesting story from the 1630s, where a group of gravediggers went on strike in the town of Monte Lupo, in Tuscany. They were the necessary workers of the time, and they went on strike because they were working in terrible, dangerous conditions and they had not been paid for their work burying those who had died of the plague.

So, what you would see are these walls, which would change their position every week to form different environments, while the environments grew richer with objects, stories, and representations. ACT UP archives that I had been researching seemed important to share in terms of the forms of organising that had been happening and how maybe we could learn from them. For example, ACT UP in 1992 took the ashes of comrades who had died during the ongoing AIDS crisis and went on this very long procession in Washington, D.C. The procession ended at the White House lawn, where they dumped the ashes—the -the bodies- of their loved ones.

In another corner of the space, I installed another piece, “On Necessary Work," which I made in collaboration with a group of nurses who were working in US hospitals and some that were working in Denmark. That 3 monitor installation was more heavily invested in thinking specifically about labour conditions during the pandemic.

Adelita Husni Bey, These Conditions, 2022, film still, three-channel high-definition video, 35:46 min. Courtesy of the artist and Castello di Rivoli collection.

Adelita Husni Bey, These Conditions, 2022, film still, three-channel high-definition video, 35:46 min. Courtesy of the artist and Castello di Rivoli collection.

And then there was a final piece in the same space called “Cronaca del tempo ripetuto,” which means The Chronicle of History is Repeating, which was entirely made in collaboration with a small self-run chamber orchestra in Tuscany in this area called Val d’Elsa, heavily hit by the plague in the 1630s. We began to explore the historical material that we found and reflect on current conditions through sound-pedagogy exercises. For example, attempting to describe and reimagine the sonic qualities of isolation during the pandemic and then walking through the streets as the town was reopening after lockdown to represent the sound and experience of that moment. I asked them to create scores based on the sounds that they were now hearing again, for the first time after lockdown.

Everything circulated and was installed around the mobile walls, which was where the film was being made and the workshops were taking place. That part, as I described, wasn’t fixed in time or space, and it was not really meant to be an art piece.