In 2022, I travelled to the occupied city of Laayoune with journalist Jacob Kushner to report on how Morocco’s government had weaponized the COVID-19 pandemic as another excuse to persecute Sahrawi independence activists. One of the tell-tale signs of the occupation is how the Moroccan flag is draped everywhere, to an extent not seen in Morocco.

READThe Continued Occupation of Western Sahara

Western Sahara has been occupied by the Kingdom of Morocco for nearly half a century. Throughout the pandemic, Morocco weaponized COVID-19 as yet another tool in its arsenal to violently repress Sahrawi independence activists, with ramifications palpable throughout Western Sahara to this day.

Ruination is the foundational violence that established the Indian nation-state. Long perfected in Indian-Occupied Kashmir over the last seven decades, camouflaged under the optics of democracy and development, it is ruination that has accelerated India’s settler-colonial project, setting the layout of demographic engineering across the region.

READLocked in Atrocity Image: The Ruination of Muslim Space and Body in India and Kashmir

How to fight brahmin supremacist violence in India and demand Kashmir’s liberation without disseminating images that spectacularise their ruination? Can we prioritise sensation over sensationalism? Do we have the collective tools to respect the rights of those who wish to remain unseen in life and in death, who do not want themselves to be reduced to a body circulating in pixel streams, their fate decided by algorithms? What measure of accountability can we honour to establish an ethic of seeing? How to build solidarities that are not conditional on these appeals of innocence?

In this essay, I take ‘disasters’ as thresholds to explain that nothing is natural about them but the underlying infrastructures and injustices that push people and beings to the brink of extinction. I further emphasise that the self-organized mutual aid networks demonstrate the necessity and potential for building alternative futures outside the deepening systems of oppression, racism, and discrimination that these disasters exacerbate.

READSurviving Unjust Lands; (im)Possible Futures

Disasters on the Turkey-Syria border expose the states’ obsolescence and collective suicide, but also people on the margins, repeatedly displaced, nonetheless building mutual aid networks to survive. These grassroots efforts offer a blueprint for a future beyond oppressive systems.

“Home” and “belonging” are peaceful, positive keywords that can cover up issues related to much less pleasant things, such as nationalism, racism, exclusion, housing commodification, power and control.

READHome Without Journey: A Review of Kiasma’s ‘Feels Like Home’ & Artsi’s ‘My Home Somewhere’

Given that concepts like ‘home’ and ‘belonging’ are used so frequently, is it still possible to do something new and impactful with them? And, if that is possible, what conditions would allow such categories to be revitalised through contemporary art and have an effect?

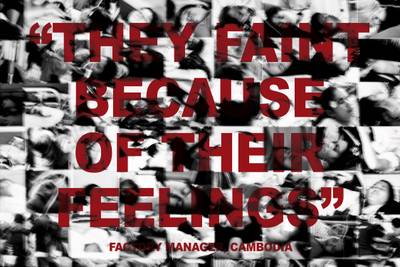

If the problems that individuals face in their personal lives are rooted in systemic issues, then it is unrealistic to expect them to find lasting solutions solely through individual self-improvement efforts. Individual change is not simply a matter of personal effort but is also shaped by the broader social conditions that individuals find themselves in. Abril’s work highlights this hypocrisy of the oppressor in a perverted patriarchal society in which women are blamed and ridiculed for showing symptoms of distress—Mass Hysteria.

READOur Bodies Protest on Our Behalf: A Review of ‘Laia Abril – On Mass Hysteria’

Laia Abril’s work On Mass Hysteria at The Festival of Political Photography challenges the focus on individual diagnosis, prompting the question, can photography be a tool for social diagnosis and change?

Nainsukh partakes of a fundamental contradiction common to movies dramatizing an artist’s work. On a basic level, the film is a self-confessed fiction based on paintings that have a concrete existence in the world. Recreating Nainsukh’s compositions with real people in real locations, however, its pro-filmic re-enactments possess an ontological reality that surpasses those of the events and personalities portrayed in the pictures. Nainsukh’s conversion of life into paintings and Dutta’s reconversion of these paintings back to life, but with a different shade of meaning, help install a critical distance between the two media.

READI’m not NAINSUKH, Nainsukh isn’t us: Artistic Process as a Cinematic Device

Exploring self-representation of visual artists and the history of the cinematic representations of artistic processes with artist biopic Nainsukh ( 2010) and its companion volume.

I met Anna Möttölä in early April, not long after she finished her seven-year term working as the executive director of L&A. Before that, I had mainly seen her introduce some of the films at the festival or lead some of the Q&As with filmmakers. In all that, something that shined through so clearly was how much she loves cinema and that, for her, this is not merely another job. I admire this quality, as I find it quite rare these days in people with higher institutional positions. Among the many things we discussed were what this job meant to her, the decision to leave it, the challenges and learning curves of the job, L&A as a political institution, and the struggles of running a festival in times of austerity.

READDirecting Helsinki’s Beloved Film Festival: An Interview with Anna Möttölä

A conversation with Anna Möttölä on the occasion of her finishing a seven-year term as Helsinki International Film Festival: Love & Anarchy’s executive director.